|

| Part of a series on |

| Muisca culture |

|---|

| Topics |

| Geography |

| The Salt People |

| Main neighbours |

| History and timeline |

.jpg.webp)

.JPG.webp)

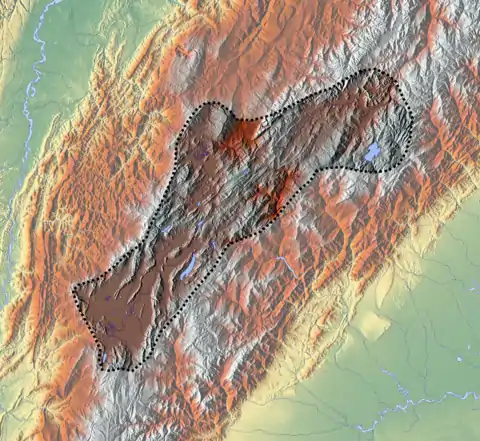

This article describes the architecture of the Muisca. The Muisca, inhabiting the central highlands of the Colombian Andes (Altiplano Cundiboyacense and the southwestern part of that the Bogotá savanna), were one of the four great civilizations of the Americas.[1] Unlike the three civilizations in present-day Mexico and Peru (the Aztec, Maya, and the Incas), they did not construct grand architecture of solid materials. While specialising in agriculture and gold-working, cloths and ceramics, their architecture was rather modest and made of non-permanent materials as wood and clay.

Evidence for the Muisca architecture relies on archaeological excavations performed since the mid 20th century. In recent years larger areas showing evidence of the Early Muisca architecture have been uncovered, the biggest of them in Soacha, Cundinamarca.[2][3] All of the original houses and temples have been destroyed by the Spanish conquerors and replaced with colonial architecture. Reconstructions of some houses (bohíos) and the most important temple in the Muisca religion; the Temple of the Sun in Sogamoso, called Sugamuxi by the Muisca, have been built in the second half of the 20th century.

Notable scholars who have contributed to the knowledge about the Muisca architecture are Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, who made the first contact with the Muisca, early 17th century friars Pedro Simón and Juan de Castellanos later bishop Lucas Fernández de Piedrahita and modern archaeologists Eliécer Silva Celis, Sylvia Broadbent, Carl Henrik Langebaek and others.

Background

The Altiplano Cundiboyacense, the high plateau in the Colombian Andes, has been inhabited for at least 12,400 years, with the earliest evidence in El Abra, Tibitó and Tequendama. During this era, the paleoclimate and flora and fauna were different from today. It was the end of the Pleistocene, when stadials and interstadials intercalated and the glaciers in the Eastern Ranges were advancing and retreating. When the first hunter-gatherers arrived from the north (the Caribbean coast and earlier from Central America), they encountered still the Pleistocene megafauna on the highlands; Cuvieronius, Stegomastodon, Haplomastodon and Equus andium in particular.[4]

During this time and age, as is evidenced in archaeological excavations at various sites on the Altiplano, the people lived in caves and rock shelters. The prehistorical period was followed by the Herrera Period, commonly dated at 800 BCE to 800 CE. It was in this era that the agricultural advancement, that started in the latest preceramic times, caused a change towards population of the plains, away from the caves and rock shelters.[5] This also led to an increase in population which was modest in the early Herrera Period and more pronounced towards the end of it; the start of the Muisca Period at around 800 CE. Further population growth and a more stratified society is observed in archaeological analysis of the Late Muisca Period, from 1200 CE onwards. The first contact with the Muisca happened in 1537 by the troops of conquistador and explorer Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada and his brother Hernán.

Muisca architecture

Houses and settlements

The houses of the Muisca, called bohíos or malokas, were circular structures made of poles of wood and walls of clay, with a conical reed roof. A long beam of wood supported the roof in the centre of the round structure and was attached to the wooden poles. The interior of the roof was decorated with cloths with thin strokes of different colours. On the floor fine straw was placed.[6] Some bohíos, probably those of the caciques had ceramic floors, as evidenced by findings in Mosquera. This was atypical for the Muisca houses.[7]

Although the Spanish chroniclers have reported "great populations" of the Muisca territories,[8] the people lived in small settlements, described by the Spanish conquerors as "dispersed homesteads". As the Maya people, the Muisca related the smaller settlements with their effective agriculture.[9] Houses on the Bogotá savanna were built on slightly elevated areas to prevent them from floodings of the various rivers, humedales and swamps, characteristic of the area.[10] Each community had their own farmlands and hunting grounds surrounding their houses. The houses were constructed around a central square with the house of the cacique in the centre. Two or more "gates" in the cercado (enclosure) gave access to the village.[11] The exact number of houses in the villages remains unclear and requires more archaeological work. De Quesada described villages of 10 up to 100 houses. The Late Muisca Period, commonly defined as 1200-1537, is characterised by denser population and larger communities, especially in Suba and Cota with more dispersed housing in the vicinity.[12]

Excavations in the Las Delicias neighbourhood of Bogotá, on an alluvial terrace of the Tunjuelito River in 1990, exposed six circular structures of 4.6 metres (15 ft) in diameter, which is slightly smaller than living spaces found in other areas, e.g. in Facatativá (5 metres (16 ft)).[13] The occupation of these houses has been dated from the start of the Muisca Period until the colonial period. The living space was occupied in two stages, starting from 950 BCE, followed by a next phase dated at 750 BCE. The dating has been done based on carbon, taken from the floors of the area. Ceramics, animal bones, swindles, seeds and jewellery has been found in this location too.[14]

Archaeologist Silva Celis uncovered in 1943 housing structures in Soacha with four different temporal levels with indications of population in the form of ash deposits from fires and animal bones.[15]

Various scholars agree that the housing of the Muisca was egalitarian; little differentiation between the living spaces of the caciques and the lower-class people has been found, especially in Soacha.[16][17]

It has been described -by Pedro Simón among others- that at the entrance posts of the houses of the caciques human sacrifice remains were hanging and the posts smeared with blood from the victims, who were regarded as sacred when they were young boys (moxas) or captured from neighbouring indigenous groups. Archaeological evidence from Mosquera supported this thesis.[18]

Roads

The roads of the Muisca people were unpaved, which makes it hard to identify them in archaeological excavations. Some of the roads were trade routes, with the eastern neighbours (Llanos Orientales), in the north with the Guane people and in the west with the Panche and Muzo, others were sacred routes. Examples of holy roads, used for pilgrimages, were found in Guasca and Siecha. Routes communicating Muisca territories with cotton producing areas ran through Somondoco and Súnuba. The roads crossing the mountains surrounding the Altiplano were narrow, making it more difficult for the Spanish conquistadores to cross them, especially with horses. Once they reached the open terrains of the Bogotá savanna, movement became easier.[19]

Temples

The Muisca, as part of their religion, built various temples throughout their territories. The most sacred were the Sun Temple in Sugamuxi and the Moon Temple in Chía. The Sun Temple was built to honour Sué, the Sun god of the Muisca, and the Moon Temple was honouring his wife, Chía. Also notable was the Goranchacha Temple, according to Muisca myths built by Goranchacha. On one of the islands in Lake Fúquene there had been a temple with grand decoration and 100 priests, as described by De Piedrahita.[20]

Pedro Simón noted that the temples were built with wood from the guayacán tree, to make them last long.[21]

According to De Piedrahita, the moxas were raised in the temples to make them as sacred as possible for when they would be sacrificed, which meant a great honour to the families who donated the young boys.[20]

Other structures

Other structures of the Muisca were mostly religious in character. Apart from their celebrations at natural areas, such as Lake Guatavita, Lake Iguaque, Lake Tota, Lake Fúquene, Lake Suesca and the Siecha Lakes, the Muisca constructed some places where religious ceremonies were held, such as the Cojines del Zaque and the Hunzahúa Well, both in Hunza, present-day Tunja.

As an exception to the wood-and-clay structures of the houses and temples of the Muisca people, allegedly one of their structures had been made of stone; the fortress of Cajicá, just north of present-day Bogotá. The structure is described with walls of 80 centimetres (31 in) thick and 4 metres (13 ft) high, but modern scientists have cast doubt on the structure and if it existed in the pre-Columbian era.[22]

Post-conquest

The first construction of post-conquest architecture took place shortly after De Quesada had conquered the city of Bacatá, later called Santafe and known as the capital Bogotá in modern age. At the location of present-day Teusaquillo, twelve houses and a church in the style of the Muisca -with wood and clay- had been constructed.[23]

It was a general policy of the Spanish, eased by the non-permanent architecture of the Muisca, that existing structures would be taken down and replaced by Spanish colonial architecture.

Reconstructions

Reconstructions of Muisca bohíos and the most important temple of Sogamoso, are displayed in the Archaeology Museum in Sogamoso. This work has been done in the early stage of archaeological research on the Altiplano, in the 1940s. Eliécer Silva Celis was the architect and archaeologist involved in the reconstructions.

Archaeological work has been hindered by the constant expansion of the capital Bogotá in which vicinity and territory many ancient structures were built. An archaeological expedition of 2002 proved that within months the previously unoccupied archaeological site was already covered with construction.[24]

See also

References

- ↑ Ocampo López, 2007, Ch.V. p.226

- ↑ (in Spanish) El descubrimiento arqueológico más grande de Colombia - Semana

- ↑ (in Spanish) Aldea premuisca enreda transmisión de luz a Bogotá - El Espectador

- ↑ Correal Urrego, 1990, p.12

- ↑ Correal Urrego, 1990, p.13

- ↑ Ocampo López, 2007, Ch.V, p.203

- ↑ Cardale de Schrimpff, 1985, p.116

- ↑ Efraín Sánchez, p.1

- ↑ Francis, 1993, p.38

- ↑ Broadbent, 1974, p.120

- ↑ Langebaek, 1995a, p.8

- ↑ Rodríguez Gallo, 2010, p.32

- ↑ Rodríguez Gallo, 2010, p.46

- ↑ Rodríguez Gallo, 2010, p.40

- ↑ Rodríguez Gallo, 2010, p.36

- ↑ Kruschek, 2003, p.180

- ↑ Henderson & Ostler, 2005, p.149

- ↑ Henderson & Ostler, 2005, p.157

- ↑ Langebaek, 1995b, Ch.1

- 1 2 Casilimas, 1987, p.135

- ↑ Henderson & Ostler, 2005, p.156

- ↑ Román, 2008, p.288

- ↑ Salcedo, 2011, p.158

- ↑ Kruschek, 2003, p.56

Bibliography

- Broadbent, Sylvia M.. 1974. La situación del Bogotá Chibcha - The Chibcha Bogotá situation. Revista Colombiana de Antropología 17. 117-132. .

- Cardale de Schrimpff, Marianne. 1985. En busca de los primeros agricultores del Altiplano Cundiboyacense - Searching for the first farmers of the Altiplano Cundiboyacense, 99–125. Banco de la República. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Casilimas Rojas, Clara Inés, and María Imelda López Ávila. 1987. El templo muisca - The Muisca temple. Maguaré 5. 127-150. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Correal Urrego, Gonzalo. 1990. Aguazuque: Evidence of hunter-gatherers and growers on the high plains of the Eastern Ranges, 1-316. Banco de la República: Fundación de Investigaciones Arqueológicas Nacionales. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Francis, John Michael. 1993. "Muchas hipas, no minas" The Muiscas, a merchant society: Spanish misconceptions and demographic change (M.A.), 1-118. University of Alberta.

- Henderson, Hope, and Nicholas Ostler. 2005. Muisca settlement organization and chiefly authority at Suta, Valle de Leyva, Colombia: A critical appraisal of native concepts of house for studies of complex societies. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 24. 148–178. .

- Kruschek, Michael H.. 2003. The evolution of the Bogotá chiefdom: A household view (PhD), 1-271. University of Pittsburgh. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Langebaek Rueda, Carl Henrik. 1995a. Heterogeneidad vs. homogeneidad en la arqueología colombiana: una nota crítica y el ejemplo de la orfebrería - Heterogeneity vs. homogeneity in the Colombian archaeology: a critical note and the example of the metallurgy. Revista de antropología y arqueología 11. 3-36. .

- Langebaek Rueda, Carl Henrik. 1995b. Los caminos aborígenes - The indigenous roads. Banco de la República. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Ocampo López, Javier. 2007. Grandes culturas indígenas de América - Great indigenous cultures of the Americas, 1–238. Plaza & Janes Editores Colombia S.A..

- Rodríguez Gallo, Diana Lorena. 2010. Construcción del paisaje agrícola al sur de la sabana de Bogotá: un desafío al agua - Agricultural landscape construction in the south of the Bogotá savanna: a challenge with water (M.A.), 1-104. Universidade de Trás‐os‐Montes e Alto Douro.

- Román, Ángel Luís. 2008. Necesidades fundacionales e historia indígena imaginada de Cajicá: una revisión de esta mirada a través de fuentes primarias (1593-1638) - Foundational needs and imagined indigenous history of Cajicá: a review of this look using primary sources (1593-1638), 276-313. Universidad de los Andes. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Salcedo Salcedo, Jaime. 2011. Un vestigio del cercado del señor de Bogotá en la traza de Santafe - A trace of the enclosure of the lord of Bogotá in the design of Santafe. Ensayos. Historia y teoría del arte 20. 155-190. .

- Sánchez, Efraín. s.a.. Muiscas, 1-6. Museo del Oro. Accessed 2016-07-08.