William Penn | |

|---|---|

Penn depicted in an 18th century illustration | |

| Born | 14 October 1644 London, England |

| Died | 30 July 1718 (aged 73) Ruscombe, Berkshire, England |

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford |

| Occupation(s) | Nobleman, writer, colonial proprietor of Pennsylvania, founder of Philadelphia |

| Spouse(s) | Gulielma Penn Hannah Margaret Callowhill |

| Children | 17, including William Jr., John, Thomas, and Richard |

| Parent(s) | Admiral Sir William Penn Margaret Jasper |

| Signature | |

William Penn (24 October [O.S. 14 October] 1644 – 10 August [O.S. 30 July] 1718) was an English writer, religious thinker, and influential Quaker who founded the Province of Pennsylvania during the British colonial era. Penn was an advocate of democracy and religious freedom known for his amicable relations and successful treaties with the Lenape Native Americans who had resided in present-day Pennsylvania prior to European settlements in the state.

In 1681, King Charles II granted a large piece of his North American land holdings along the North Atlantic Ocean coast to Penn to offset debts he owed Penn's father, the admiral and politician Sir William Penn. The land included the present-day states of Pennsylvania and Delaware. The following year, in 1682, Penn left England for what was then British America, sailing up Delaware Bay and the Delaware River past earlier Swedish and Dutch riverfront colonies in what is present-day New Castle, Delaware.[1] On this occasion, the colonists pledged allegiance to Penn as their new proprietor, and the first Pennsylvania General Assembly was held.

Penn then journeyed further north up the Delaware River and founded Philadelphia on the river's western bank. Penn's Quaker government was not viewed favorably by the previous Dutch, Swedish and English settlers in what is now Delaware, and in addition to this, the land was claimed for half a century by the neighboring Province of Maryland's proprietor family, the Calverts and Lord Baltimore. These earlier colonists had no historical allegiance to Pennsylvania, and almost immediately began petitioning for their own representative assembly. Twenty-three years later, in 1704, they achieved their goal when the three southernmost counties of provincial Pennsylvania along the western coast of the Delaware River were granted permission to split off and become the new semi-autonomous Delaware Colony. As the most prominent, prosperous and influential settlement in the new colony, New Castle, the original Swedish colony town became the colony's first capital.

As one of the earlier supporters of colonial unification, Penn wrote and urged for a union of all the English colonies in what, following the American Revolutionary War, later became the United States. The democratic principles that he included in the West Jersey Concessions and set forth in the Pennsylvania Frame of Government inspired delegates to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia to frame the U.S. Constitution, which was ratified by the delegates in 1787.[2]

A man of deep religious conviction, Penn authored numerous works, exhorting believers to adhere to the spirit of Primitive Christianity.[3] Penn was imprisoned several times in the Tower of London due to his faith, and his book No Cross, No Crown, published in 1669, which he authored from jail, has become a classic of Christian theological literature.[4]

Biography

Early years

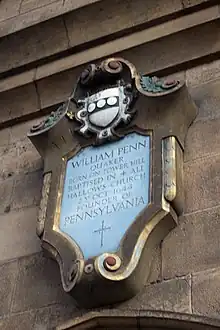

Penn was born in 1644 at Tower Hill, London, the son of English naval officer Sir William Penn, and Dutchwoman Margaret Jasper, who was widow of a Dutch sea captain and the daughter of a rich merchant from Rotterdam.[5] Admiral Penn served in the Commonwealth Navy during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms and was rewarded by Oliver Cromwell with estates in Ireland. The lands given to Penn had been confiscated from Irish Confederates who had participated in the Irish Rebellion of 1641. Admiral Penn took part in the restoration of King Charles II and was eventually knighted and served in the Royal Navy. At the time of his son's birth, then-Captain Penn was twenty-three and an ambitious naval officer in charge of blockading ports held by Confederate forces.[6]

Penn grew up during the rule of Oliver Cromwell, who succeeded in leading a Puritan rebellion against King Charles I; the king was beheaded when Penn was four years old.[7] Penn's father was often at sea. Young William caught smallpox, and lost all his hair from the disease; he wore a wig until he left college. Penn's smallpox also prompted his parents to move from the suburbs to an estate in Essex.[8] The country life made a lasting impression on young Penn, and kindled in him a love of horticulture.[9] Their neighbor was the diarist Samuel Pepys, who was friendly at first but later secretly hostile to the Admiral, perhaps embittered in part by his failed seductions of both Penn's mother and his sister Peggy.[10]

After a failed mission to the Caribbean, Admiral Penn and his family were exiled to his lands in Ireland when Penn was about 15-years-old. During this time, Penn met Thomas Loe, a Quaker missionary who was maligned by both Catholics and Protestants. Loe was admitted to the Penn household, and during his discourses on the Inward Light, young Penn recalled later that "the Lord visited me and gave me divine Impressions of Himself."[11]

A year later, Cromwell was dead, the Royalists were resurging, and the Penn family returned to England. The middle class aligned itself with the Royalists and Admiral Penn was sent on a secret mission to bring back exiled Prince Charles. For his role in restoring the monarchy, Admiral Penn was knighted and gained a powerful position as Lord Commissioner of the Admiralty.[12]

Education

Penn was first educated at Chigwell School, then by private tutors in Ireland, and later at Christ Church at the University of Oxford in Oxford.[13] At the time, there were no state schools and nearly all educational institutions were affiliated with the Anglican Church. Children from poorer families had to have a wealthy sponsor to get an education. Penn's education heavily leaned on the classical authors and "no novelties or conceited modern writers" were allowed, including Shakespeare.[14] Running was Penn's favorite sport, and he often ran more than three miles (5 km) from his home to the school, which was cast in an Anglican model and was strict, humorless, and somber. The school's teachers had to be pillars of virtue and provide sterling examples to their pupils.[15] Penn later opposed Anglicanism on religious grounds, but he absorbed many Puritan behaviors, and was known later for his own serious demeanor, strict behavior, and lack of humor.[7]

In 1660, Penn arrived at the University of Oxford, where he was enrolled as a gentleman scholar with an assigned servant. The student body was a volatile mix of swashbuckling Cavaliers, who were largerly aristocratic Anglicans, sober Puritans, and non-conforming Quakers. The new British government's discouragement of religious dissent gave the Cavaliers license to harass the minority groups. Because of his father's high position and social status, young Penn was firmly a Cavalier but his sympathies lay with the persecuted Quakers. To avoid conflict, Penn withdrew from the fray and became a reclusive scholar.[16] During this time, Penn developed his individuality and philosophy of life. He found that he was not sympathetic with either his father's martial view of the world or his mother's society-oriented sensibilities. "I had no relations that inclined to so solitary and spiritual way; I was a child alone. A child was given to musing, occasionally feeling the divine presence," he later said.[17]

Penn returned home for the extraordinary splendor of the King's restoration ceremony and was a guest of honor alongside his father, who received a highly unusual royal salute for his services to The Crown.[16] Penn's father had great hopes for his son's career under the favor of the King. Back at Oxford, Penn considered a medical career and took some dissecting classes. Rational thought began to spread into science, politics, and economics, which he took a liking to. When theologian John Owen was fired from his deanery, Penn and other open-minded students rallied to his side and attended seminars at the dean's house, where intellectual discussions covered the gamut of new thought.[18] Penn learned the valuable skills of forming ideas into theory, discussing theory through reasoned debate, and testing the theories in the real world.

At this time he also faced his first moral dilemma. After Owen was censured again after being fired, students were threatened with punishment for associating with him. However, Penn stood by the dean, thereby gaining a fine and reprimand from the university.[19] The Admiral, despairing of the charges, pulled young Penn away from Oxford, hoping to distract him from the heretical influences of the university.[20] The attempt had no effect and father and son struggled to understand each other. Back at school, the administration imposed stricter religious requirements including daily chapel attendance and required dress. Penn rebelled against enforced worship and was expelled. His father, in a rage, attacked young Penn with a cane and forced him from their home.[21] Penn's mother made peace in the family, which allowed her son to return home but she quickly concluded that both her social standing and her husband's career were being threatened by their son's behavior. So at age 18, young Penn was sent to Paris to get him out of view, improve his manners, and expose him to another culture.[22]

In Paris at the court of young Louis XIV, Penn found French manners far more refined than the coarse manners of his countrymen, but he did not like the extravagant display of wealth and privilege he saw in the French.[23] Though impressed by Notre Dame and the Catholic ritual, he felt uncomfortable with it. Instead, he sought out spiritual direction from French Protestant theologian Moise Amyraut, who invited Penn to stay with him in Saumur for a year.[24] The undogmatic Christian humanist talked of a tolerant, adapting view of religion which appealed to Penn, who later stated, "I never had any other religion in my life than what I felt."[25] By adapting his mentor's belief in free will, Penn felt unburdened of Puritanical guilt and rigid beliefs and was inspired to search out his own religious path.[26]

Upon returning to England after two years abroad, he presented to his parents a mature, sophisticated, well-mannered, modish gentleman, though Samuel Pepys noted young Penn's "vanity of the French".[27] Penn had developed a taste for fine clothes, and for the rest of his life would pay somewhat more attention to his dress than most Quakers. The Admiral had great hopes that his son then had the practical sense and the ambition necessary to succeed as an aristocrat. He had young Penn enroll in law school but soon his studies were interrupted.

With war with the Dutch imminent, young Penn decided to shadow his father at work and join him at sea.[28] Penn functioned as an emissary between his father and the King, then returned to his law studies. Worrying about his father in battle he wrote, "I never knew what a father was till I had wisdom enough to prize him... I pray God... that you come home secure."[29] The Admiral returned triumphantly, but London was in the grip of the Great Plague of 1665. Young Penn reflected on the suffering and the deaths, and the way humans reacted to the epidemic. He wrote that the scourge "gave me a deep sense of the vanity of this World, of the Irreligiousness of the Religions in it."[30] Further he observed how Quakers on errands of mercy were arrested by the police and demonized by other religions, even accused of causing the plague.[31]

With his father laid low by gout, young Penn was sent to Ireland in 1666 to manage the family landholdings. While there he became a soldier and took part in suppressing a local Irish rebellion. Swelling with pride, he had his portrait painted wearing a suit of armor, his most authentic likeness.[32] His first experience of warfare gave him the sudden idea of pursuing a military career, but the fever of battle soon wore off after his father discouraged him, "I can say nothing but advise to sobriety...I wish your youthful desires mayn't outrun your discretion."[33] While Penn was abroad, the Great Fire of 1666 consumed central London. As with the plague, the Penn family was spared.[34] But after returning to the city, Penn was depressed by the mood of the city and his ailing father, so he went back to the family estate in Ireland to contemplate his future. The reign of King Charles had further tightened restrictions against all religious sects other than the Anglican Church, making the penalty for unauthorized worship imprisonment or deportation. The "Five Mile Act" prohibited dissenting teachers and preachers to come within that distance of any borough.[35] The Quakers were especially targeted and their meetings were deemed undesirable.

Religious conversion

Despite the dangers, Penn began to attend Quaker meetings near Cork. A chance re-meeting with Thomas Loe confirmed Penn's rising attraction to Quakerism.[36] Soon Penn was arrested for attending Quaker meetings. Rather than state that he was not a Quaker and thereby avoid any charges, he publicly declared himself a member and finally joined the Quakers at the age of 22.[37] In pleading his case, Penn stated that since the Quakers had no political agenda (unlike the Puritans) they should not be subject to laws that restricted political action by minority religions and other groups. Sprung from jail because of his family's rank rather than his argument, Penn was immediately recalled to London by his father. The Admiral was severely distressed by his son's actions and took the conversion as a personal affront.[38] His father's hopes that Penn's charisma and intelligence would win him favor at the court were crushed.[39] Though enraged, the Admiral tried his best to reason with his son but to no avail. His father not only feared for his own position but that his son seemed bent on a dangerous confrontation with the Crown.[40] In the end, young Penn was more determined than ever, and the Admiral felt he had no option but to order his son out of the house and to withhold his inheritance.[41]

As Penn became homeless, he began to live with Quaker families.[41] Quakers were relatively strict Christians in the 17th century. They refused to bow or take off their hats to social superiors, believing all men equal under God, a belief antithetical to an absolute monarchy that believed the monarch divinely appointed by God. As a result, Quakers were treated as heretics because of their principles and their failure to pay tithes. They also refused to swear oaths of loyalty to the King believing that this was following the command of Jesus not to swear. The basic ceremony of Quakerism was silent worship in a meeting house, conducted in a group.[36] There was no ritual and no professional clergy, and many Quakers disavowed the concept of original sin. God's communication came to each individual directly, and if so moved, the individual shared his revelations, thoughts, or opinions with the group. Penn found all these tenets to sit well with his conscience and his heart.

Penn became a close friend of George Fox, the founder of the Quakers, whose movement started in the 1650s during the tumult of the Cromwellian revolution. The times sprouted many new sects besides Quakers, including Seekers, Ranters, Antinomians, Seventh Day Baptists, Soul sleepers, Adamites, Diggers, Levellers, Behmenists, Muggletonians, and others, as the Puritans were more tolerant than the monarchy had been.[42][43] Following Oliver Cromwell's death, however, the Crown was re-established and the King responded with harassment and persecution of all religions and sects other than Anglicanism. Fox risked his life, wandering from town to town, and he attracted followers who likewise believed that the "God who made the world did not dwell in temples made with hands."[44] By abolishing the church's authority over the congregation, Fox not only extended the Protestant Reformation more radically, but he helped extend the most important principle of modern political history – the rights of the individual – upon which modern democracies were later founded.[45] Penn traveled frequently with Fox, through Europe and England. He also wrote a comprehensive, detailed explanation of Quakerism along with a testimony to the character of George Fox, in his introduction to the autobiographical Journal of George Fox.[46] In effect, Penn became the first theologian, theorist, and legal defender of Quakerism, providing its written doctrine and helping to establish its public standing.[47]

Penn in Ireland (1669–1670)

In 1669,[48] Penn traveled to Ireland to deal with his father's estates. While there, he attended many meetings and stayed with leading Quaker families. He became a great friend of William Morris, a leading Quaker figure in Cork, and often stayed with Morris at Castle Salem near Rosscarbery.

Penn in Germany (1671–1677)

Between 1671 and 1677, Penn visited Germany on behalf of the Quaker faith, resulting in a German settlement in the Province of Pennsylvania that was symbolic in two ways: It was a German-speaking congregation, and it included religious dissenters. During the colonial era, Pennsylvania remained the heartland for various branches of Anabaptists, including Old Order Mennonites, Ephrata Cloister, Brethren, and Amish.

Pennsylvania quickly emerged as the home for many Lutheran refugees from Catholic provinces, such as Salzburg, and for German Catholics, who were facing discrimination in their home country.

In Philadelphia, Francis Daniel Pastorius negotiated the purchase of 15,000 acres (61 km2) from his friend William Penn, the proprietor of the province of Pennsylvania, and laid out the settlement of what is the present-day Germantown section of Philadelphia. In 1764, the German Society of Pennsylvania was established, which still functions to this day from its headquarters in Philadelphia.

Persecutions and imprisonments

In 1668, Penn published the first of many pamphlets, Truth Exalted: To Princes, Priests, and People. He was a critic of all religious groups, except Quakers, which he saw as the only true Christian group at that time in England. He branded the Catholic Church "the Whore of Babylon", defied the Church of England, and called the Puritans "hypocrites and revelers in God". He lambasted all "false prophets, tithemongers, and opposers of perfection".[49] Pepys thought it a "ridiculous nonsensical book" that he was "ashamed to read".[50]

In 1668, after writing a follow-up tract, The Sandy Foundation Shaken, Penn was imprisoned in the Tower of London. The Bishop of London ordered that Penn be held indefinitely until he publicly recanted his written statements. The official charge was publication without a licence but the real crime was blasphemy, as signed in a warrant by King Charles II.[51] Placed in solitary confinement in an unheated cell and threatened with a life sentence, Penn was accused of denying the Trinity, though this was a misinterpretation Penn himself refuted in the essay Innocency with her open face, presented by way of Apology for the book entitled The Sandy Foundation Shaken, where he sought to prove the Godhead of Christ.[52]

Penn said the rumor had been "maliciously insinuated" by detractors who wanted to create a bad reputation to Quakers.[53]

Penn later said that what he really denied were the Catholic interpretations of this theological topic, and the use of unbiblical concepts to explain it.[54][55][56] Penn expressly confessed he believed in the Holy Three and the divinity of Christ.[57]

In 1668, in a letter to the anti-Quaker minister Jonathan Clapham, Penn wrote: "Thou must not, reader, from my querying thus, conclude we do deny (as he hath falsely charged us) those glorious Three, which bear record in heaven, the Father, Word, and Spirit; neither the infinity, eternity and divinity of Jesus Christ; for that we know he is the mighty God."[58][59]

Given writing materials in the hope that he would put on paper his retraction, Penn wrote another inflammatory treatise, No Cross, No Crown: A Discourse Shewing The Nature and Discipline of the Holy Cross of Christ and that the Denial of Self, and Daily Hearing of Christ's Cross, is the Alone Way to Rest and Kingdom of God. In it, Penn exhorted believers to adhere to the spirit of Primitive Christianity. This work was remarkable for its historical analysis and citation of 68 authors whose quotations and commentary he had committed to memory and was able to summon without any reference material at hand.[60] Penn petitioned for an audience with the King, which was denied but which led to negotiations on his behalf by one of the royal chaplains. Penn declared, "My prison shall be my grave before I will budge a jot: for I owe my conscience to no mortal man."[51] He was released after eight months of imprisonment.[61]

Penn demonstrated no remorse for his aggressive stance and vowed to keep fighting against the wrongs of the Church and the King. For its part, the Crown continued to confiscate Quaker property and jailed thousands of Quakers. From then on, Penn's religious views effectively exiled him from English society; he was expelled from Christ Church, a college at the University of Oxford, for being a Quaker, and was arrested several times. In 1670, he and William Mead were arrested. Penn was accused of preaching before a gathering in the street, which Penn deliberately provoked to test the validity of the 1664 Conventicle Act, just renewed in 1670, which denied the right of assembly to "more than five persons in addition to members of the family, for any religious purpose not according to the rules of the Church of England".[62]

Penn was assisted by his solicitor, Thomas Rudyard, an eminent London Quaker lawyer,[63] and pleaded for his right to see a copy of the charges laid against him and the laws he had supposedly broken, but the Recorder of London, Sir John Howel, on the bench as chief judge, refused, although this was a right guaranteed by law. Furthermore, the Recorder directed the jury to come to a verdict without hearing the defense.[64][65]

Despite heavy pressure from Howel to convict Penn, the jury returned a verdict of "not guilty". When invited by the Recorder to reconsider their verdict and to select a new foreman, they refused and were sent to a cell over several nights to mull over their decision. The Lord Mayor of London, Sir Samuel Starling, also on the bench, then told the jury, "You shall go together and bring in another verdict, or you shall starve", and not only had Penn sent to jail in Newgate Prison (on a charge of contempt of court for refusing to remove his hat), but the full jury followed him, and they were additionally fined the equivalent of a year's wages each.[66][67] The members of the jury, fighting their case from prison in what became known as Bushel's Case, managed to win the right for all English juries to be free from the control of judges.[68] This case was one of the more important trials that shaped the concept of jury nullification[69] and was a victory for the use of the writ of habeas corpus as a means of freeing those unlawfully detained.

With his father dying, Penn wanted to see him one more time and patch up their differences. But he urged his father not to pay his fine and free him, "I entreat thee not to purchase my liberty." But the Admiral refused to let the opportunity pass and he paid the fine, releasing his son.

His father had gained respect for his son's integrity and courage and told him, "Let nothing in this world tempt you to wrong your conscience."[70] The Admiral also knew that after his death young Penn would become more vulnerable in his pursuit of justice. In an act which not only secured his son's protection but also set the conditions for the founding of Pennsylvania, the Admiral wrote to the Duke of York, the heir to the throne.

The Duke and the King, in return for the Admiral's lifetime of service to the Crown, promised to protect young Penn and make him a royal counselor.[71]

Penn inherited a large fortune, but found himself in jail again for six months. In April 1672, after being released, he married Gulielma Springett following a four-year engagement filled with frequent separations. Penn remained close to home but continued writing his tracts, espousing religious tolerance and railing against discriminatory laws.[72] A minor split developed in the Quaker community between those who favored Penn's analytical formulations and those who preferred Fox's simple precepts.[73] But the persecution of Quakers had accelerated and the differences were overridden; Penn again resumed missionary work in Holland and Germany.[74]

Founding of Pennsylvania

.jpg.webp)

Seeing conditions deteriorating, Penn appealed directly to the King and the Duke, proposing a mass emigration of English Quakers. Some Quakers had already moved to North America, but the New England Puritans, especially, were as hostile towards Quakers as Anglicans in England were, and some of the Quakers had been banished to the Caribbean.[75]

In 1677, a group of prominent Quakers that included Penn purchased the colonial province of West Jersey, comprising the western half of present-day New Jersey.[76] The same year, 200 settlers from Chorleywood and Rickmansworth in Hertfordshire, and other towns in nearby Buckinghamshire arrived, and founded the town of Burlington. Fox made a journey to America to verify the potential of further expansion of the early Quaker settlements.[77] In 1682, East Jersey was also purchased by Quakers.[78][79]

With the Province of New Jersey in place, Penn pressed his case to extend the Quaker region. Whether from personal sympathy or political expediency, to Penn's surprise, the King granted an extraordinarily generous charter which made Penn the world's largest private non-royal landowner, with over 45,000 square miles (120,000 km2).[80]: 64 Penn became the sole proprietor of a huge tract of land west of New Jersey and north of the Province of Maryland belonging to Lord Baltimore, and gained sovereign rule of the territory with all rights and privileges with the exception of the power to declare war. The land of Pennsylvania had belonged to the Duke of York, but he retained the Province of New York and the area around present-day New Castle, Delaware, and the eastern portion of the Delmarva Peninsula.[81] In return, one-fifth of all gold and silver mined in the province, which had virtually none, was to be remitted to the King, and the Crown was freed of a debt to the Admiral of £16,000, equal to roughly £2,668,049 in 2008.[82]

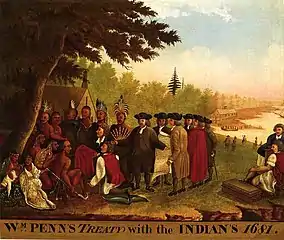

Penn first called the area "New Wales", then "Sylvania", which is Latin for "forests" or "woods", which King Charles II changed to "Pennsylvania" in honor of the elder Penn.[83] On 4 March 1681, the King signed the charter and the following day Penn jubilantly wrote, "It is a clear and just thing, and my God who has given it to me through many difficulties, will, I believe, bless and make it the seed of a nation."[84] Penn then traveled to America and while there, he negotiated Pennsylvania's first land-purchase survey with the tribe of the Lenape people. Penn purchased the first tract of land under a white oak tree at Graystones on 15 July 1682.[85] Penn drafted a charter of liberties for the settlement creating a political utopia guaranteeing free and fair trial by jury, freedom of religion, freedom from unjust imprisonment and free elections.[86]

Having proved himself an influential scholar and theoretician, Penn now had to demonstrate the practical skills of a real estate promoter, city planner, and governor for his "Holy Experiment", the province of Pennsylvania.[87]

Besides achieving his religious goals, Penn had hoped that Pennsylvania would be a profitable venture for himself and his family. But he proclaimed that he would not exploit either the natives or the immigrants, "I would not abuse His love, nor act unworthy of His providence, and so defile what came to me clean."[88] To that end, Penn's land purchase from the Lenape included the latter party's retained right to traverse the sold lands for purposes of hunting, fishing, and gathering.[89]

Though thoroughly oppressed, getting Quakers to leave England and make the dangerous journey to the New World was his first commercial challenge. Some Quaker families had already arrived in Maryland and New Jersey but the numbers were small. To attract settlers in large numbers, he wrote a glowing prospectus, considered honest and well-researched for the time, promising religious freedom as well as material advantage, which he marketed throughout Europe in various languages. Within six months, he parcelled out 300,000 acres (1,200 km2) to over 250 prospective settlers, mostly rich London Quakers.[90] Eventually he attracted other persecuted minorities including Huguenots, Mennonites, Amish, Catholics, Lutherans, and Jews from England, France, Holland, Germany, Sweden, Finland, Ireland, and Wales.[91]

Penn then began establishing the legal framework for an ethical society where power was derived from the people, from "open discourse", in much the same way as a Quaker Meeting was run. Notably, as the sovereign, Penn thought it important to limit his own power as well.[92] The new government would have two houses, safeguard the rights of private property and free enterprise, and impose taxes fairly. It called for death for only two crimes, treason and murder, rather than the two hundred crimes under English law, and all cases were to be tried before a jury.[93] Prisons would be progressive, attempting to correct through "workshops" rather than through hellish confinement.[94] The laws of behavior he laid out were rather Puritanical: swearing, lying, and drunkenness were forbidden as well as "idle amusements" such as stage plays, gambling, revels, masques, cock-fighting, and bear-baiting.[95]

All this was a radical departure from the laws and the lawmaking of European monarchs and elites. Over 20 drafts, Penn labored to create his "Framework of Government", with the assistance of Thomas Rudyard, the London Quaker lawyer who assisted Penn in his defense during the Penn-Mead case in 1670, and was later deputy-governor of East New Jersey.[63] He borrowed liberally from John Locke who later had a similar influence on Thomas Jefferson, but added his own revolutionary idea – the use of amendments – to enable a written framework that could evolve with the changing times.[96] He stated, "Governments, like clocks, go from the motion men give them."[97]

Penn hoped that an amendable constitution would accommodate dissent and new ideas and also allow meaningful societal change without resorting to violent uprisings or revolution.[98] Remarkably, though the Crown reserved the right to override any law it wished, Penn's skillful stewardship did not provoke any government reaction while Penn remained in his province.[99] Despite criticism by some Quaker friends that Penn was setting himself above them by taking on this powerful position, and by his enemies who thought he was a fraud and "falsest villain upon earth", Penn was ready to begin the "Holy Experiment".[100] Bidding goodbye to his wife and children, he reminded them to "avoid pride, avarice, and luxury".[101]

Under Penn's direction, Philadelphia was planned and developed and emerged as the largest and most influential city in the Thirteen Colonies. Philadelphia was planned out to be grid-like with its streets and be very easy to navigate, unlike London. The streets are named with numbers and tree names.

Return to England

In 1684, Penn returned to England to see his family and to try to resolve a territorial dispute with Lord Baltimore.[102] Penn did not always pay attention to details and had not taken the fairly simple step of determining where the 40th degree of latitude (the southern boundary of his land under the charter) actually was. After he sent letters to several landowners in Maryland advising the recipients that they were probably in Pennsylvania and not to pay any more taxes to Lord Baltimore, trouble arose between the two proprietors.[103] This led to an eighty-year legal dispute between the two families.

Political conditions at home had stiffened since Penn left. To his dismay, he found Bridewell and Newgate prisons filled with Quakers. Internal political conflicts even threatened to undo the Pennsylvania charter. Penn withheld his political writings from publication as "The times are too rough for print."[104]

In 1685 King Charles died, and the Duke of York was crowned James II. The new king resolved the border dispute in Penn's favor. But King James, a Catholic with a largely Protestant parliament, proved a poor ruler, stubborn and inflexible.[105] Penn supported James' Declaration of Indulgence, which granted toleration to Quakers, and went on a "preaching tour through England to promote the King's Indulgence".[106] His proposal at the London Yearly Meeting of the Society of Friends in June 1688 to establish an "advisory committee that might offer counsel to individual Quakers deciding whether to take up public office" under James II was rebuffed by George Fox, who argued that it was "not safe to conclude such things in a Yearly Meeting".[107] Penn offered some assistance to James II's campaign to regulate the parliamentary constituencies by sending a letter to a friend in Huntingdon asking him to identify men who could be trusted to support the king's campaign for liberty of conscience.[108]

Penn faced serious problems in the colonies due to his sloppy business practices. Apparently, he could not be bothered with administrative details, and his business manager, fellow Quaker Philip Ford, embezzled substantial sums from Penn's estates. Ford capitalized on Penn's habit of signing papers without reading them. One such paper turned out to be a deed transferring ownership of Pennsylvania to Ford who then demanded a rent beyond Penn's ability to pay.

Return to America

After agreeing to let Ford keep all his Irish rents in exchange for remaining quiet about Ford's legal title to Pennsylvania, Penn felt his situation sufficiently improved to return to Pennsylvania with the intention of staying.[109] Accompanied by his wife Hannah, daughter Letitia and secretary James Logan, Penn sailed from the Isle of Wight on the Canterbury, reaching Philadelphia in December 1699.[110]

Penn received a hearty welcome upon his arrival and found his province much changed in the intervening 18 years. Pennsylvania grew rapidly. It had nearly 18,100 inhabitants, and Philadelphia had over 3,000.[111] His tree plantings were providing the green urban spaces he had envisioned. Shops were full of imported merchandise, satisfying the wealthier citizens and proving America to be a viable market for English goods. Most importantly, religious diversity was succeeding.[112] Despite the protests of fundamentalists and farmers, Penn's insistence that Quaker grammar schools be open to all citizens was producing a relatively educated workforce. High literacy and open intellectual discourse led to Philadelphia becoming a leader in science and medicine.[113] Quakers were especially modern in their treatment of mental illness, decriminalizing insanity and turning away from punishment and confinement.[114]

The tolerant Penn transformed himself almost into a Puritan, in an attempt to control the fractiousness that had developed in his absence, tightening up some laws.[115] Another change was found in Penn's writings, which had mostly lost their boldness and vision. In those years, he did put forward a plan to make a federation of all English colonies in America. There have been claims that he also fought slavery, but that seems unlikely, as he owned and even traded slaves himself and his writings do not support that idea. However, he did promote good treatment for slaves, including marriage among slaves, though rejected by the council. Other Pennsylvania Quakers were more outspoken and proactive, being among the earliest fighters against slavery in America, led by Francis Daniel Pastorius and Abraham op den Graeff, founders of Germantown, Pennsylvania. Pastorius, Op den Graeff, his brother Derick op den Graeff, both of whom were Penn's cousins, and Garret Hendericks, signed the 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery. Many Quakers pledged to release their slaves upon their death, including Penn, and some sold their slaves to non-Quakers.[116]

The Penns lived comfortably at Pennsbury Manor and had all intentions of living out their lives there. They also had a residence in Philadelphia. Their only American child, John, had been born and was thriving. Penn was commuting to Philadelphia on a six-man barge, which he admitted he prized above "all dead things".

James Logan, his secretary, kept him acquainted with all the news. Penn had plenty of time to spend with his family and still attend to affairs of state, though delegations and official visitors were frequent. His wife, however, did not enjoy life as a governor's wife and hostess and preferred the simple life she led in England. When new threats by France again put Penn's charter in jeopardy, Penn decided to return to England with his family, in 1701.[117]

Later years

Penn returned to England and immediately became embroiled in financial and family troubles. His eldest son William Jr. was leading a dissolute life, neglecting his wife and two children, and running up gambling debts. Penn had hoped to have William succeed him in America.[118] Now he could not even pay his son's debts. His own finances were in turmoil. He had sunk over £30,000 (equal to £5,179,899 today) in America and received little back except for some bartered goods. He had made many generous loans which he failed to press.[119]

Philip Ford, Penn's financial advisor, cheated Penn out of thousands of pounds by concealing and diverting rents from Penn's Irish lands, claiming losses, then extracting loans from Penn to cover the shortfall. When Ford died in 1702, his widow Bridget threatened to sell Pennsylvania, to which she claimed title.[120] Penn sent William to America to manage affairs, but he proved just as unreliable as he had been in England. There were considerable discussions about scrapping his constitution.[121] In desperation, Penn tried to sell Pennsylvania to The Crown before Bridget Ford got wind of his plan, but by insisting that the Crown uphold the civil liberties that had been achieved, he could not strike a deal. Ford took her case to court. At age 62, Penn landed in debtors' prison; however, a rush of sympathy reduced Penn's punishment to house arrest, and Bridget Ford was finally denied her claim to Pennsylvania. A group of Quakers arranged for Ford to receive payment for back rents and Penn was released.[122]

In 1712, Berkeley Codd, Esq. of Sussex County, Delaware disputed some of the rights of Penn's grant from the Duke of York. Some of William Penn's agents hired lawyer Andrew Hamilton to represent the Penn family in this replevin case. Hamilton's success led to an established relationship of goodwill between the Penn family and Andrew Hamilton.[123] Penn had grown weary of the politicking back in Pennsylvania and the restlessness with his governance, but Logan implored him not to forsake his colony, for fear that Pennsylvania might fall into the hands of an opportunist who would undo all the good that had been accomplished.[124] During his second attempt to sell Pennsylvania back to the Crown in 1712, Penn suffered a stroke. A second stroke several months later left him unable to speak or take care of himself. He slowly lost his memory.[118]

Death

In 1718, at age 73, Penn died penniless, at his home in Ruscombe, near Twyford in Berkshire, and is buried in a grave next to his first wife, Gulielma, in the cemetery of the Jordans Quaker meeting house near Chalfont St Giles in Buckinghamshire. His second wife, Hannah, as sole executor, became the de facto proprietor until she died in 1726.[125]

Family

Penn first married Gulielma Maria Posthuma Springett (1644–1694), daughter of William S. Springett; the Posthuma in her name indicates that her father had died prior to her birth, and Lady Mary Proude Penington. They had three sons and five daughters:[126]

- Gulielma Maria (23 January 1673 – 17 May 1673)

- William and Mary (or Maria Margaret) (twins) (born February 1674 and died May 1674 and December 1674)

- Springett (25 January 1675 – 10 April 1696)

- Letitia (1 March 1678 – 6 April 1746), who married William Awbrey (Aubrey)

- William Jr. (14 March 1681 – 23 June 1720)

- Unnamed child (born March 1683 and died April 1683)

- Gulielma Maria (November 1685–November 1689)

Two years after Gulielma's death he married Hannah Margaret Callowhill (1671–1726), daughter of Thomas Callowhill and Anna (Hannah) Hollister. William Penn married Hannah when she was 25 and he was 52. They had nine children in twelve years:

- Unnamed daughter (born and died 1697)

- John Penn (28 January 1700 – 25 October 1746), who never married

- Thomas Penn (20 March 1702 – 21 March 1775), married Lady Juliana Fermor, fourth daughter of Thomas, first Earl of Pomfret

- Hannah Penn (1703–1706)

- Margaret Penn (7 November 1704–February 1751), married Thomas Freame (1701/02–1746) nephew of John Freame, founder of Barclays Bank

- Richard Penn Sr. (17 January 1706 – 4 February 1771)

- Dennis Penn (26 February 1707 – 1723)

- Hannah Margarita Penn (1708–March 1708)

- Louis Penn

Legacy

According to American historian Mary Maples Dunn:

Penn liked money and although he was certainly sincere about his ambitions for a "holy experiment" in Pennsylvania, he also expected to get rich. He was, however, extravagant, a bad manager and businessman, and not very astute in judging people and making appointments... Penn was gregarious, had many friends, and was good at developing the useful connections which protected him through many crises. Both his marriages were happy, and he would describe himself as a family man, all the public affairs took him away from home a great deal and he was disappointed in those children whom he knew as adults.[127]

After Penn's death, the Province of Pennsylvania slowly drifted away from a colony founded by religion to a secular state dominated by commerce. Many of Penn's legal and political innovations took root, however, as did the Quaker school in Philadelphia for which Penn issued two charters (1689 and 1701). The institution, a notable secondary school and the world's oldest Quaker school, was later renamed the William Penn Charter School in Penn's honor.

Voltaire praised Pennsylvania as the only government in the world that responds to the people and is respectful of minority rights. Penn's "Frame of Government" and his other ideas were later studied by Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Paine, whose father was a Quaker. Among Penn's legacies was his unwillingness to force a Quaker majority upon Pennsylvania, allowing his state to develop into a successful melting pot, with multiple religions. Thomas Jefferson and the Founding Fathers adopted Penn's theory of an amendable constitution and his vision that "all Persons are equal under God", as he informed the federal government following the American Revolution. In addition to his extensive political and religious treatises, Penn also authored nearly 1,000 maxims, full of observations about human nature and morality.[128]

Penn's family retained ownership of the province of Pennsylvania until the end of the American Revolution and Revolutionary War. However, William's son and successor, Thomas Penn, and his brother John, renounced their father's faith, and fought to restrict religious freedom (particularly for Catholics and later Quakers as well). Thomas weakened or eliminated the elected assembly's power, and ran Pennsylvania instead through governors who he appointed. He was a bitter opponent of Benjamin Franklin, and Franklin's push for greater democracy in the years leading up to the American Revolution. Through the Walking Purchase in 1737, the Penns cheated the Lenape out of their lands in the Lehigh Valley.[129]

As a pacifist Quaker, Penn considered the problems of war and peace deeply. He developed a forward-looking project and thoughts for a United States of Europe through the creation of a European Assembly made of deputies who could discuss and adjudicate controversies peacefully. He is considered the first intellectual to suggest the creation of a European Parliament and what became the present-day European Union in the late 20th century.[130]

Posthumous honors

_Seal_of_Confidence.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

- On October 24, 1932, the U.S. Post Office issued a 3-cent postage stamp to commemorate the 250th anniversary of Penn's arrival to the British-American colonies.[131]

- On 28 November 1984, then U.S. President Ronald Reagan issued a presidential proclamation declaring Penn and his second wife Hannah Callowhill Penn both honorary citizens of the United States.[132]

- A bronze statue of William Penn by Alexander Milne Calder stands atop Philadelphia City Hall. When installed in 1894, the statue represented the highest point in the city, as City Hall was then the tallest building in Philadelphia. Urban designer Edmund Bacon was known to have said that no gentleman would build taller than the "brim of Billy Penn's hat". This agreement existed for almost 100 years until the city decided to allow taller skyscrapers to be built. In March 1987, the completion of One Liberty Place was the first building to do that. This resulted in a "curse" which lasted from that year on until 2008 when a small statue of William Penn was put on top of the newly built Comcast Center. The Philadelphia Phillies went on to win the 2008 World Series that year.

- A lesser-known statue of Penn is located at Penn Treaty Park, on the site where Penn entered into his treaty with the Lenape, which is famously commemorated in the painting Penn's Treaty with the Indians. In 1893, Hajoca Corporation, the nation's largest privately held wholesale distributor of plumbing, heating, and industrial supplies, adopted the statue as its trademark symbol.[133]

- The Quaker Oats cereal brand standing "Quaker man" logo, dating back to 1877, was identified in their advertising after 1909 as William Penn, and referred to him as "standard bearer of the Quakers and of Quaker Oats".[134][135] In 1946, the logo was changed into a head-and-shoulders portrait of the smiling Quaker Man. The Quaker Oats Company's website currently claims their logo is not a depiction of William Penn.[136]

- Bil Keane created the comic Silly Philly for the Philadelphia Bulletin, a juvenile version of Penn, that ran from 1947 to 1961.

- Penn was depicted in the 1941 film Penn of Pennsylvania by Clifford Evans.

- William Penn High School for Girls was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1986.[137] The William Penn House – a Quaker hostel and seminar center – was named in honor of William Penn when it opened in 1966 to house Quakers visiting Washington, D.C. to partake in the many protests, events and social movements of the era.[138]

- Chigwell School, the school he attended, has named one of their four houses after him and now owns several letters and documents in his handwriting.

- William Penn Primary School, and the successor Penn Wood Primary and Nursery School, in Manor Park, Slough, near to Stoke Park, is named after William Penn.[139]

- A pub in Rickmansworth, where Penn lived for a time, is named the Pennsylvanian in his honour, and a picture of him is used as the pub sign.[140]

- The Friends' School, Hobart has named one of their seven six-year classes after him.

- The William Penn Society of Whittier College has existed since 1934 as a society on the college campus of Whittier College and continues to this day.

- William Penn University in Oskaloosa, Iowa, which was founded by Quaker settlers in 1873, was named in his honor. Penn Mutual, a life insurance company established in 1847, also bears his name.

- Streets named after William Penn include Penn Avenue, a major arterial street in Pittsburgh and Wilkinsburg, Pennsylvania, Penn Avenue in Scranton, and Penn Street in Bristol, Pennsylvania.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "New Castle History". New Castle Crier. Archived from the original on 14 July 2011.

- ↑ Murphy, Andrew R. (2019). William Penn : a life. New York. pp. 117–118. ISBN 978-0190234249.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ See his work Primitive Christianity Revived (1696)

- ↑ Thomas Nelson (2009). "NKJV American Patriot's Bible." Thomas Nelson Inc. p. 1358.

- ↑ Hans Fantel, William Penn: Apostle of Dissent, William Morrow & Co., New York, 1974, p. 6, ISBN 0-688-00310-9

- ↑ Fantel, p. 6

- 1 2 Fantel, p. 15

- ↑ Bonamy Dobrée, William Penn: Quaker and Pioneer, Houghton Mifflin Co., 1932, New York, p. 3

- ↑ Fantel, p. 12

- ↑ Fantel, p. 16

- ↑ Fantel, p. 23

- ↑ Fantel, pp. 25, 32

- ↑ "William Penn", Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2nd ed. 17 Vols. Gale Research, 1998. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale. 2007.

- ↑ Fantel, p. 13

- ↑ Fantel, p. 14

- 1 2 Fantel, p. 29

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 9

- ↑ Fantel, p. 35

- ↑ Fantel, p. 37

- ↑ Fantel, p. 38

- ↑ Fantel, p. 43

- ↑ Fantel, p. 45

- ↑ Fantel, p. 49

- ↑ Fantel, p. 51

- ↑ Fantel, p. 52

- ↑ Fantel, p. 53

- ↑ Fantel, p. 54

- ↑ Fantel, p. 57

- ↑ Fantel, p. 59

- ↑ Fantel, p. 60

- ↑ Fantel, p. 61

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 23

- ↑ Fantel, p. 63

- ↑ Fantel, p. 64

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 21

- 1 2 Fantel, p. 69

- ↑ Fantel, p. 72

- ↑ Fantel, p. 75

- ↑ Fantel, p. 76

- ↑ Fantel, p. 77

- 1 2 Fantel, p. 79

- ↑ Fantel, p. 83

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 63

- ↑ Fantel, pp. 80–81

- ↑ Fantel, p. 84

- ↑ Journal of George Fox Archived 3 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine (retrieved 25 September 2007)

- ↑ Fantel, p. 88

- ↑ William Penn (1669–1670) My Irish Journal, edited by Isabel Grubb, Longmans, 1952

- ↑ Fantel, p. 97

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 43

- 1 2 Fantel, p. 101

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Londinensis, or, Universal dictionary of arts, sciences, and literature Archived 22 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Volume 19, (1823). p. 543

- ↑ Hicks, Elias. "A Defence of the Christian doctrines of the Society of Friends: being a reply to the charge of denying the three that bear record in heaven" (1825), pp. 35–37: "This conclusive argument for the proof of Christ, the Saviour's, being God, should certainly persuade all sober persons of my innocence, and my adversaries malice. He that is the everlasting Wisdom, Divine Power, the true Light, the only Saviour, the creating Word of all things, whether visible or invisible, and their upholder, by his own power, is, without contradiction God – but all these qualifications, and divine properties, arc by the concurrent testimonies of Scripture, ascribed to the Lord Jesus Christ; therefore, without a scruple, I call and believe him, really to be, the mighty God.

- ↑ "A Brief Answer to a False and Foolish Libel called The Quakers Opinions for their Sakes that Writ it and Read it" (1678). Sect. V, "-Perversion 9-: 'The Quakers deny the Trinity'. -Principle-: Nothing less. They believe in the Holy Three, or Trinity of Father, Word, and Spirit, according to Scripture. And that these Three are Truly and Properly Oe: Of One Nature as well as Will. But they are very tender of quitting Scripture Terms and ¿¿Phrases for Schoolmen's, such as distinct and separate Persons and Substances, etc. are, from whence People are apt to entertain gross Ideas and Notions of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost."

- ↑ Penn, William. (1726). A Collection of the Works of William Penn, Vol. 2. J. Sowle. p. 783.

- ↑ Themis Papaioannou. "Early Quakers and the Trinity Archived 28 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine." Christian Quaker.

- ↑ Penn, William. (1726). A Collection of the Works of William Penn, Vol. 2. J. Sowle. p. 783: Sect. VI. "Of the Divinity of Christ. -Perversion- 10. 'The Quakers deny Christ to be God'. -'Principle'-: "A most Untrue and Unreasonable Censure: For their Great and Characteristics principle being this, That Christ, as the Divine Word, Lighten the Souls of all Men that come into the World, with a Spiritual and Saving Light, according to John 1. 9. ch. 8.12 (which nothing but the Creator of Souls can do) it does sufficiently shew they believe him to be God, for they truly and expressly own him to be so, according to Scripture, viz: 'In him was Life, and that Life the Light of Men, and He is God over all, blessed forever."

- ↑ Richardson, John (1829), The Friend: A Religious and Literary Journal, Volume 2. p. 77

- ↑ Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme. (1817). The Monthly Repository of Theology and General Literature, Volume 12. p. 348

- ↑ Fantel, p. 105

- ↑ Fantel, p. 108

- ↑ Dixon, William (1851). William Penn: An Historical Biography. Philadelphia: Blanchard and Lea. pp. 75, 76.

- 1 2 Soderlund, Jean R. (1983). William Penn and the Founding of Pennsylvania (1st ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 113. ISBN 0-8122-1131-6.

- ↑ Fantel, pp. 117–120

- ↑ Duhaime, Lloyd. "1670: The Jury Earns Its Independence (Bushel's case)". duhaime.org. Lloyd Duhaime. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ↑ Fantel, p. 124

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 71

- ↑ Lehman, Godfrey (1996). The Ordeal of Edward Bushell. Lexicon. ISBN 978-1-879563-04-9.

- ↑ Abramson, Jeffrey (1994). We, The Jury. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. pp. 68–72. ISBN 978-0-674-00430-6.

- ↑ Fantel, p. 126

- ↑ Fantel, p. 127

- ↑ Fantel, pp. 139–140

- ↑ Fantel, p. 143

- ↑ Fantel, p. 145

- ↑ See, for example, the story of Jan Claus, a gold- and silversmith who was arrested under the English Conventicle Act 1664, convicted and sentenced to ship to Jamaica, survived an on-board plague that killed half the passengers, was captured by a privateer, was taken back to the Netherlands and imprisoned, and finally saved by Friends who took him to settle in Amsterdam.

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 102

- ↑ Fantel, p. 147

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 117

- ↑ "Brief Biography of William Penn". www.ushistory.org. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ↑ Randall M. Miller and William Pencak, ed., Pennsylvania: A History of the Commonwealth, Penn State University Press, 2002, p. 59, ISBN 0-271-02213-2

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 119

- ↑ Fantel, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 120

- ↑ Fantel, p. 149

- ↑ Graystones ~ The Treaty for Pennsylvania Archived 9 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, buckscountyintime blog, accessed 25 November 2015

- ↑ "William Penn (English Quaker leader and colonist)". Britannica. Archived from the original on 31 December 2008. Retrieved 27 June 2009.

In 1682 (England), he drew up a Frame of Government for the Pennsylvania colony. Freedom of worship in the colony was to be absolute, and all the traditional rights of Englishmen were carefully safeguarded

- ↑ Fantel, p. 150

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 128

- ↑ Suzan Shown Harjo, ed., Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States & American Indian Nations, Smithsonian Institution, 2014, p. 61

- ↑ Fantel, pp. 152–153

- ↑ Fantel, p. 194

- ↑ Fantel, p. 159

- ↑ Fantel, p. 161

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 148

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 149

- ↑ Fantel, p. 156

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 131

- ↑ Fantel, p. 157

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 150

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 135

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 138

- ↑ Fantel, p. 199

- ↑ Soderlund, Jean R. (ed.) William Penn and the Founding of Pennsylvania Univ. Penn. Press (1983), p. 79

- ↑ Fantel, p. 203

- ↑ Fantel, p. 209

- ↑ Harris, Tim Revolution:The Great Crisis of the British Monarchy 1685–1720 Allen Lane (2006) p. 218

- ↑ Sowerby, Scott, Making Toleration: The Repealers and the Glorious Revolution Harvard University Press (2013), p. 144

- ↑ Sowerby, p. 140.

- ↑ Fantel, p. 237

- ↑ Scharf, John Thomas and Thompson Wescott (1884), History of Philadelphia, 1609–1884, Volume II, Philadelphia: L.H. Everts & Co., p. 1686: "In December 1699, when William Penn made his second visit to Pennsylvania, he brought with him his second wife, Hannah Callowhill Penn, and Letitia Penn, his daughter by his first wife."

- ↑ Miller and Pencak, p. 61

- ↑ Fantel, p. 240

- ↑ Fantel, p. 242

- ↑ Fantel, p. 244

- ↑ Fantel, p. 246

- ↑ Fantel, p. 251

- ↑ Fantel, p. 253

- 1 2 Fantel, p. 254

- ↑ Fantel, pp. 255–266

- ↑ Fantel, p. 258

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 286

- ↑ Fantel, pp. 260–261

- ↑ Fisher, Joshua Francis; Ffrench, John; Cadwalader, John; Sharpas, William; Alexander, J.; Smith, W. (April 1892). "Andrew Hamilton, Esq., of Pennsylvania". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 16 (1): 2.

- ↑ Dobrée, p. 313

- ↑ Miller and Pencak, p. 70

- ↑ "Genealogies of Pennsylvania Families"

- ↑ John A. Garraty, ed. ‘’Encyclopedia of American Biography (1974) p. 847.

- ↑ William Penn Tercentenary Committee, Remember William Penn, 1944

- ↑ Miller and Pencak, p. 76

- ↑ See Daniele Archibugi, William Penn, the Englishman who invented the European Parliament Archived 31 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine openDemocracy, 28 May 2014.

- ↑ Scott Specialized catalogue of U.S. Postage Stamps, 1982, p. 94

- ↑ Proclamation of Honorary US Citizenship for William and Hannah Penn Archived 17 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine by President Ronald Reagan (1984)

- ↑ "Hajoca Lancaster". Hajoca Lancaster. Archived from the original on 26 October 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ↑ "If it walks like William Penn, talks like William Penn and looks like William Penn …". 18 March 2013. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ↑ "Quaker Oats box label, circa 1920s". crystalradio.net. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ↑ "About Quaker – Quaker FAQ". Quaker Oats Company. Archived from the original on 25 October 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 9 July 2010.

- ↑ History Archived 27 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. William Penn House. Retrieved on 23 July 2013.

- ↑ "Home – Penn Wood Primary and Nursery School". www.pennwood.slough.sch.uk. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- ↑ "The Pennsylvanian Rickmansworth – J D Wetherspoon". www.jdwetherspoon.com.

Further reading

- Dunn, Mary Maples. William Penn: Politics and Conscience (1967)

- Dunn, Richard S. and Mary Maples Dunn, eds. The World of William Penn (1986), essays by scholars

- Endy, Melvin B. Jr. William Penn and Early Quakerism (1973)

- Geiter, Mary K. William Penn (2000)

- Moretta, John. William Penn and the Quaker Legacy (2006)

- Morgan, Edmund S. "The World and William Penn," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society (1983) 127#5 pp. 291–315 JSTOR 986499.

- Murphy, Andrew R. William Penn: A Life (2018)

- Nash, Gary B. Quakers and Politics: Pennsylvania, 1681–1726 (1968)

- Peare, Catherine O. William Penn (1957), a standard biography

- Soderlund, Jean R. "Penn, William" in American National Biography Online (2000) Access Date: Nov 04 2013

- Vulliamy, C.E. William Penn (1933)

Primary sources

- Dunn, Mary Maples, and Richard S. Dunn et al., eds. The Papers of William Penn (5 vols., 1981–1987)

- Soderlund, Jean R. et al., eds. William Penn and the Founding of Pennsylvania, 1680–1684: A Documentary History (1983)

- Seitz, Don Carlos, ed. (1919). The tryal of William Penn & William Mead for causing a tumult, at the sessions held at the Old Bailey in London the 1st, 3d, 4th, and 5th of September 1670. Boston: Marshall Jones Company.

External links

- Lesson Plan: William Penn's Peaceable Kingdom Archived 12 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- William Penn Appleton and Klos Biography

- The Life of William Penn by M. L. Weems, 1829. Full-text free to read and search version of Tim Unterreiner biography from 1829 original published in Philadelphia.

- William Penn, Visionary Proprietor by Tuomi J. Forrest, at the University of Virginia

- William Penn, America's First Great Champion for Liberty and Peace by Jim Powell

- William Penn by Bill Samuel

- Penn's Holy Experiment: The Seed of a Nation Archived 11 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Penn in the Tower of London Archived 31 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Hidden London Penn in the Tower

- original version of this article (copied with permission)

- "Pennsylvania's Anarchist Experiment: 1681–1690," Prof. Murray N. Rothbard, excerpt from Conceived in Liberty, Vol. 1 (Auburn, Alabama: The Ludwig von Mises Institute, 1999)

- William Penn at Find a Grave

- Penn Treaty Museum

Penn's works

- Works by William Penn at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Penn at Internet Archive

- Works by William Penn at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- No Cross, No Crown (1669). 2nd edition published in 1682. Written during his imprisonment in the Tower of London.

- The Christian Quaker, and his divine testimony vindicated by Scripture, reason, and authorities, against the injurious attempts ... lately made ... to render him odiously inconsistent with Christianity and Civil Society. In II. Parts., (1674).(part one written by Penn; Part two by George Whitehead, 1673).

- True Spiritual Liberty (1681)

- Some Fruits of Solitude in Reflections and Maxims (1682)

- Frame Of Government Of Pennsylvania (1682) From the Avalon Project, Yale Law School.

- Letter to his wife, Gulielma (1682)

- Early Quaker writings contains several documents by Penn and his wife.

- A Key Archived 28 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine (1692)

- Primitive Christianity Revived Archived 5 April 2005 at the Wayback Machine (1696)

- Preface to George Fox's Journal Archived 3 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine (1694)

- The Rise and Progress of the People Called Quakers by William Penn (1905 ed.)

- An Essay towards the Present and Future Peace of Europe by the Establishment of a European Dyet, Parliament or Estates (1693)

- William Penn & Richard Claridge (1817). Anonymous (ed.). Extracts from The Writings of William Penn & Richard Claridge, on the Death and Sufferings of Our Lord Jesus Christ. London: William and Samuel Graves. Retrieved 3 January 2010. Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org)

- Dunn, Mary Maples, Dunn, Richard S., Bronner, Edwin, and Fraser, David. The papers of William Penn, 5 volumes. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1981–87.