| Post-exertional malaise | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Post-exertional symptom exacerbation (PESE) Postexertional malaise |

| |

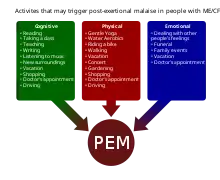

| Chart of physical, cognitive, and emotional activities that may trigger PEM | |

| Symptoms | Worsening of symptoms after ordinary activity |

| Causes | Chronic fatigue syndrome Long COVID |

| Treatment | Symptomatic |

Post-exertional malaise (PEM), sometimes referred to as post-exertional symptom exacerbation (PESE),[1] is a worsening of chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) or long COVID symptoms that occurs after exertion.[1] PEM is often severe enough to be disabling, and is triggered by ordinary activities that healthy people tolerate. Typically, it begins 12–48 hours after the activity that triggers it, and lasts for days, but this is highly variable and may persist much longer.[2][3][4] Management of PEM is symptom-based, and patients are recommended to pace their activities to avoid triggering PEM.

History

One of the first definitions of ME/CFS, the Holmes Criteria published in 1988, does not use the term post-exertional malaise but describes prolonged fatigue after exercise as a symptom.[5] The term was later used in a 1991 review summarizing the symptoms of ME/CFS. Afterwards, the Canadian Consensus Criteria from 2003[6] and the International Consensus Criteria from 2011[7] used the term, as well as later definitions.

Description

Post-exertional malaise involves an exacerbation of symptoms, or the appearance of new symptoms, which are often severe enough to impact a person's functioning.[8] While fatigue is often prominent, it is "more than fatigue following a stressor".[4] Other symptoms that may occur during PEM include cognitive impairment, flu-like symptoms, pain, weakness, and trouble sleeping.[4][2] Though typically cast as a worsening of existing symptoms, patients may experience some symptoms exclusively during PEM.[4] Patients often describe PEM as a "crash", "relapse", or "setback".[4]

PEM is triggered by "minimal"[3] physical or mental activities that were previously tolerated, and that healthy people tolerate, like attending a social event, grocery shopping, or even taking a shower.[2] Sensory overload,[8] emotional distress, injury, sleep deprivation, infections, and spending too long standing or sitting up are other potential triggers.[4] The resulting symptoms are disproportionate to the triggering activity and are often debilitating, potentially rendering someone housebound or bedbound until they recover.[9][4][10][2]

The course of a crash is highly variable. Symptoms typically begin 12–48 hours after the triggering activity,[3] but may be immediate, or delayed up to 7 days.[4] PEM lasts "usually a day or longer",[9] but can span hours, days, weeks, or months.[4] The level of activity that triggers PEM, as well as the symptoms, vary from person to person, and within individuals over time.[4] Due to this variability, affected people may be unable to predict what will trigger it.[2] This variable, relapsing-remitting pattern can cause one's abilities to fluctuate from one day to the next.[1]

Diagnosis

PEM is a hallmark symptom of ME/CFS and is common in long COVID.[11][12][13]

However, its presence can be difficult to assess because patients and doctors may be unfamiliar with it.[1][12] Hence, the WHO recommends that clinicians explicitly ask long COVID patients whether symptoms worsen with activity.[1]

The 2-day Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test (CPET) may aid in documenting PEM, showing apparent abnormalities in the body's response to exercise.[14] Still, more research on developing a diagnostic test is needed.

Epidemiology

PEM is considered a cardinal symptom of ME/CFS by modern diagnostic criteria: the International Consensus Criteria,[2][9] the National Academy of Medicine criteria,[15][16] and NICE's definition of ME/CFS[10] all require it. The Canadian Consensus Criteria require "post exertional malaise and/or [post exertional] fatigue" instead.[17][18][19][15][20] On the other hand, the older Oxford Criteria lack any mention of PEM,[21] and the Fukuda Criteria consider it optional. Depending on the definition of ME/CFS used, PEM is present in 60 to 100% of ME/CFS patients.[4]

Studies have found that a majority of people with long COVID experience post-exertional malaise as well.[12]

Management

There is no treatment or cure for PEM. Pacing, a management strategy in which someone plans their activities to stay within their limits, may help avoid triggering PEM.[22]

Physical therapy for people with long COVID must be modified to avoid triggering PEM in susceptible patients.[23]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Clinical management of COVID-19 Living Guideline. World Health Organization. 13 January 2023. pp. 113–4. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): Symptoms". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 14 July 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Terms: Post-exertional malaise". Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy)/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management - Recommendations. NICE (Report). 29 October 2021. NICE guideline NG206.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness" (PDF). National Academy of Medicine. 2015. pp. 78–86. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ↑ Holmes, Gary P. (1988-03-01). "Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Working Case Definition". Annals of Internal Medicine. 108 (3): 387–389. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-108-3-387. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 2829679.

- ↑ Carruthers, Bruce M.; Jain, Anil Kumar; De Meirleir, Kenny L.; Peterson, Daniel L.; Klimas, Nancy G.; Lerner, A. Martin; Bested, Alison C.; Flor-Henry, Pierre; Joshi, Pradip; Powles, A. C. Peter; Sherkey, Jeffrey A.; van de Sande, Marjorie I. (January 2003). "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Clinical Working Case Definition, Diagnostic and Treatment Protocols". Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 11 (1): 7–115. doi:10.1300/J092v11n01_02. ISSN 1057-3321.

- ↑ Carruthers, B. M.; van de Sande, M. I.; De Meirleir, K. L.; Klimas, N. G.; Broderick, G.; Mitchell, T.; Staines, D.; Powles, A. C. P.; Speight, N.; Vallings, R.; Bateman, L.; Baumgarten-Austrheim, B.; Bell, D. S.; Carlo-Stella, N.; Chia, J. (October 2011). "Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria". Journal of Internal Medicine. 270 (4): 327–338. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x. ISSN 0954-6820. PMC 3427890. PMID 21777306.

- 1 2 Grach, Stephanie L.; Seltzer, Jaime; Chon, Tony Y.; Ganesh, Ravindra (October 2023). "Diagnosis and Management of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 98 (10): 1544–1551. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.07.032. PMID 37793728. S2CID 263665180.

- 1 2 3 Carruthers, B. M.; van de Sande, M. I.; De Meirleir, K. L.; Klimas, N. G.; Broderick, G.; Mitchell, T.; Staines, D.; Powles, A. C. P.; Speight, N.; Vallings, R.; Bateman, L.; Baumgarten-Austrheim, B.; Bell, D. S.; Carlo-Stella, N.; Chia, J.; Darragh, A.; Jo, D.; Lewis, D.; Light, A. R.; Marshall-Gradisbik, S.; Mena, I.; Mikovits, J. A.; Miwa, K.; Murovska, M.; Pall, M. L.; Stevens, S. (October 2011). "Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria". Journal of Internal Medicine. 270 (4): 327–338. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x. PMC 3427890. PMID 21777306.

- 1 2 "1.2 Suspecting ME/CFS". Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy)/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management – Recommendations. NICE (Report). 29 October 2021. NICE guideline NG206.

- ↑ "Information for Healthcare Providers | ME/CFS | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2022-11-11. Retrieved 2023-06-07.

- 1 2 3 Davis, Hannah E.; McCorkell, Lisa; Vogel, Julia Moore; Topol, Eric J. (13 January 2023). "Long COVID: major findings, mechanisms and recommendations". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 21 (3): 133–146. doi:10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2. ISSN 1740-1534. PMC 9839201. PMID 36639608.

- ↑ "Long COVID or Post-COVID Conditions". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1 September 2022.

- ↑ Eun-Jin, Lim; Eun-Bum, Kang; Eun-Su, Jang; Chang-Gue, Son (2020). "The Prospects of the Two-Day Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test (CPET) in ME/CFS Patients: A Meta-Analysis". Journal of Clinical Medicine. J Clin Med. 9 (12): 4040. doi:10.3390/jcm9124040. PMC 7765094. PMID 33327624.

- 1 2 "IOM 2015 Diagnostic Criteria | Diagnosis | Healthcare Providers | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2018-11-08. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- ↑ "Symptoms of ME/CFS | Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS)". CDC. 2021-01-27.

- ↑ Myhill, Sarah; Booth, Norman E; McLaren-Howard, John (2009). "Chronic fatigue syndrome and mitochondrial dysfunction" (PDF). Int J Clin Exp Med. 2 (1): 1–16. PMC 2680051. PMID 19436827.

- ↑ Carruthers, Bruce M; van de Sande, Marjorie I. (2005). "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Clinical Case Definition and Guidelines for Medical Practitioners" (PDF). sacfs.asn.au. p. 8.

There is an inappropriate loss of physical and mental stamina, rapid muscular and cognitive fatigability, post exertional malaise and/or fatigue and/or pain and a tendency for other associated symptoms within the patient's cluster of symptoms to worsen.

- ↑ "Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) Key Facts" (PDF). nap.edu. 2015. p. 2.

- ↑ Wright Clayton, Ellen; Alegria, Margarita; Bateman, Lucinda; Chu, Lily; Cleeland, Charles; Davis, Ronald; Diamond, Betty; Ganlats, Theodore; Keller, Betsy (2015). "Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelits/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness (Report Guide for Clinicians)" (PDF). nationalacademies.org. Nancy Klimas, A. Martin Lerner, Cynthia Mulrow, Benjamin Natelson, Peter Rowe, Michael Shelanski. National Academy of Medicine (Institutes of Medicine). p. 7.

- ↑ Sharpe, Michael (February 1991). "A report--chronic fatigue syndrome: guidelines for research". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 84 (2): 118–121. doi:10.1177/014107689108400224. PMC 1293107. PMID 1999813.

- ↑ "1.11 Managing ME/CFS". Myalgic encephalomyelitis (or encephalopathy)/chronic fatigue syndrome: diagnosis and management – Recommendations. NICE (Report). 29 October 2021. NICE guideline NG206.

- ↑ Clinical management of COVID-19 Living Guideline. World Health Organization. 13 January 2023. p. 109. Retrieved 14 January 2023.