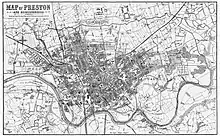

Preston Dock (also known as Preston Docklands) was a former maritime dock located on the northern bank of the River Ribble approximately 2.5 km (1.6 mi) west of Preston's city centre in Lancashire, England. It is the location of the Albert Edward Basin which opened in 1892 and is connected to the river by a series of locks.

The dock is 25.6 km (15.9 mi) from the Irish Sea and provided a port for shipping until its closure in 1981.[1] Most of the historic buildings and facilities have since been demolished and the area is now mainly commercial and residential property, along with some light industry. Following the dock's closure, a public marina was opened in 1987.[2]

History

Prehistory

The prehistory of the lands around what is now the Preston Docks, and the use of the River Ribble as a waterway dates back many thousands of years.[2] Excavation for the docks in the 1880s uncovered neolithic artefacts around 6,000 to 10,000 years old, some of which can be viewed in Preston's Harris Museum.[3]

Pre-Industrial Revolution

Historical evidence shows that the Ribble played a role by ancient and pre-medieval cultures in their conquest of Britain, with artefacts of Saxon, Roman and Viking origin recovered from the lands surrounding the river banks.[2]

Records from medieval times show that Preston was already a trading port by the 12th century when a portmote (a type of court[4]) would meet at regular intervals to give judgement on matters relating to the operation of the port,[2] and increasing trade through the port was recorded from around the mid-14th century.[5] Even in these early times, the Ribble suffered from silt deposits, and the first recorded instance of the river being dredged to improve passage dates to the 16th century.[6]

18th century

The Industrial Revolution saw a boom in the textile industry in Lancashire and Preston was no exception; by the end of 18th century around a dozen large mills had sprung up across the town. Textiles were not Preston's only industry; the abolition of the town's royal charter in 1790 as a Guild Town permitted freedom of trade, and other manufacturing industries quickly began to emerge.[7] New markets were soon found for these goods, with many being shipped to overseas destinations. There was also an ever-increasing influx of timber, coal and cotton for the town's mills and factories, food for its growing population, and later, wood pulp for the paper mills at the near-by town of Darwen.[8]

Ships would come up-river to Preston to unload and shelter in a natural basin known in its time as 'Preston Anchorage', where the Moorbrook joined the Ribble,[lower-alpha 1] where the town's original docks were located.[5] However, by the last decade of the 18th century the town's wharf facilities were already struggling to keep up with demand, with the shallowness of the river limiting ships - particularly larger ones- to around the time of high tides, and by loading and unloading facilities and storage warehouses built on marshlands surrounding the river banks which were prone to flooding.[2]

19th century

In the early 1800s the Preston Consortium was founded which along with representation from the town council (which retained 30% ownership of the corporation) included some of Preston's largest private companies, to propose ways in which the river could be better used to facilitate trade. This led to the creation of the first Ribble Navigation Company in 1806, whose primary purpose was to commence a program of land reclamation and fixing the course of the river within training walls built along its banks. Construction of a new wharf commenced a few years later further downstream along the section of the river where Marsh Lane joined Strand Road. The new wharves, known as the New Quays (later renamed to Victoria Quay), opened in 1825.[6] Construction commenced on supporting infrastructure with the Victoria Bonded Warehouse off Strand Road opening in 1843 and a number of shipyards built along the banks of the river.[10] In 1846 a branch line was opened from Preston Railway Station to what was now Victoria Quay to provide a direct rail link to the docks.[8]

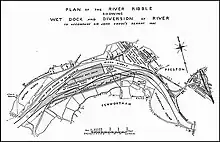

The shallowness of the river was still an issue and in 1837 the famous engineer Robert Stevenson was commissioned by the corporation to develop plan to merge the river's multiple channels together into a single course and making it deep enough to be safely navigable by larger vessels. As a result, a 22.5 km (14.0 mi) channel, the Gut,[lower-alpha 2] was dredged in the river up to its estuary at Lytham. The second Ribble Navigation Company was created in 1838 and lasted until 1853, followed by the third company in 1853 which lasted until 1883. Both of these companies continued the work of the first, dredging and fixing the course of the river and by 1880 around 445 hectares (1,100 acres) of land along the surrounding banks had been reclaimed.[1] The third company was bestowed with more power for land reclamation not only for the docks but also to benefit Preston overall, and created around 1,600 hectares (4,000 acres) of new farmland from the former tidal stretches and mudflats.

However, even with the new deeper navigation channel there was still an ongoing issue of the river's shallowness which not only limited vessels' journeys but also restricted the mooring of increasingly larger vessels to the new Victoria Quays (which, by 1860, had only been in operation for 35 years) and in 1861 the Preston Consortium discussed a proposal to locate the docks away from the river in deeper water with a constant level maintained by a series of locks. Nothing came from this proposal until 1882 when the corporation voted to adopt this as their strategy for their town's future port. In 1883, Parliament passed the Preston Dock Act to allow construction of the new docks.[1] In 1884 construction began with the diversion of the River Ribble and the excavation of the new basin, with the first sod being turned on 11 October 1884.[2] On 17 July 1885 the dock's foundation stone was laid by Queen Victoria's eldest son, Albert Edward the Prince of Wales, after whom the basin is named.[12]

The dock was officially opened on 25 June 1892 by Alfred, the Prince of Edinburgh, Queen Victoria's second eldest son, and the new Port of Preston commenced operations.[12] The first ship to enter the lock and use the new docks was the steam yacht Aline, carrying the royal party for the opening ceremony. There are contrary records as to what was the commercial vessel to use the new docks, with some saying it was SS Lady Louise, chartered by the Lancashire firm EH Booth and Co Ltd (still operating today as the upmarket supermarket chain Booths), and which carried an inbound load of cargo, while others say it was the Hebe, which unloaded a cargo of cement. However, was is not disputed is the fanfare that accompanied the opening of the docks, with over 10,000 members of the public in attendance and a "flotilla" of small boats and pleasure craft on the Ribble.

20th century

From its slow beginnings the docks experience a steady growth in trade in the early decades of the 20th century. With the outbreak of the First World War the docks took on a new role, exporting munitions produced by local factories that had been retooled for the war effort. After the cessation of hostilities the docks experienced a downturn in trade from which it never fully recovered in the inter-war period. In the 1920s the rail line from the site of the old Victory Quay was extended along both side of the docks, allowing an increase in the volume of goods transiting to and from the port.

During the Second World War the docks again aided Britain's war effort, when it was taken over by the military and used as a marshalling post for the D-Day landings in Normandy, 1944. During the course of the war the docks had to be closed twice due to naval mines.[6] In the years after the Second World War, the volume of goods passing in and out of the port increased, aided by a ferry service to Northern Ireland commencing in 1948. Traffic increased even further until a peak in the 1960s, but warning signs for its future were beginning to appear. Ferry services ceased by the early 1970s, and although containerised cargo meant ships could be loaded and unloaded more quickly, economies of scale meant container vessels increased in size, and the age-old problem of the shallowness of the Ribble took greater significance; constant dredging operations were now costing around half of the port's annual income.

The period 1960–1972 was the busiest in the dock's history but from then it experienced a continued and noticeable fall in revenue brought about from a reduction in trade and the cost of dredging required to keep the port open, and in 1981 an Act of Parliament was passed to close the docks. On 22 October 1981 the last Preston-based ship, the dredger Hoveringham V left the docks and on 31 October, the port's last official day of operation, the Singapore-based MV Sea Rhine became the final vessel to leave the docks, thus signalling the closure of the Port of Preston.

Post-redevelopment

Following redevelopment of the former Preston Dock, greater emphasis has been placed upon the role that Riversway and the Albert Edward Basin play in the community's leisure and lifestyle, and the area has hosted several significant events:

- During the 2012 Preston Guild celebrations, held every 20 years and unique within Great Britain, Riversway played an important role, especially with the year's Riversway Festival when more than 60 guest boats entered the basin. The Royal Navy patrol boat HMS Charger, a semi-regular visitor to the city, was formally adopted by Preston, allowing the vessel and its crew to "officially" participate in the celebrations.[13]

- The Riversway Festival (formerly the Preston Maritime Festival) was an annual summer event first held in the 1992 Preston Guild to celebrate the city's maritime heritage. Various activities are held on the basin, including a dragon boat regatta, a dinghy "grand prix", displays by the Sea Cadets and brightly decorated guest vessels including narrowboats from the Lancaster Canal. Following the 2012 festival the council cancelled funding for the event due to budget cuts and the 2013 festival, which only went ahead due to the efforts of volunteers, was the last occurrence of this event. There have been subsequent discussions to resurrect the festival but no outcome has been forthcoming.[14]

- The Ribble Steam Railway, which has operated on former docklands railway facilities since 2005, hosts weekend steam train excursions which have proven popular with locals and tourists. Around 2010, the company proposed the construction of a new station at the Strand Road level crossing to attract more tourists (given its close proximity to Preston station), and possibly extend their line westward out to the Ribble Link. Preliminary approval was granted by the council[15] but plans appear to have fallen through due to lack of funding. However, the company is continuing expanding its facilities with the construction of a "Railway Exploration Centre".[16]

- In 2019 a community volunteer group CLEARED (Community Led Action to Revitalise the Dock) has been formed to clean up the docks and the waters of the basin, and in particular, to address the issue of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria).[17]

Albert Edward Basin and Dock

The Albert Edward Basin is 3,000 feet (910 m) long by 600 feet (180 m) wide[lower-alpha 3] and covers an area of around 42 acres (17 ha), and provided over 1.8 km (1.1 mi) of quayside for loading and unloading vessels. At it opening in 1892 it was the largest:

The main basin flows into a short canal approximately 200 metres (660 ft) long, at the end of which is a series of lock gates to control the level of water in the basin. The canal then flows into a tidal basin of around 15 acres in area, at the end of which is another lock gate before another short canal approximately 100 metres (330 ft) long which flows into the River Ribble. The water in the basin is maintained to a level within a 2-metre (6 ft 7 in) range, originally by staff of the Preston Corporation, and now by the Preston City Council, who operate the lock gates (and since 1985, the swing bridge) to permit the passage of craft to and from the river. When the basin's water levels drop, they are topped up by water from the Ribble on spring tides.[2] The size of vessels that can enter the basin are constrained by the length of the boat lock and the width of the lock gates.

The cost of building the basin and operating the docks (including on-going dredging of the river) proved a financial burden, and in its 90-year history the port only reported a profit on 17 years.[1]

Construction

The need for a new dock immune from the Ribble's tides was first proposed by the Preston Corporation in 1861. In 1882 the corporation officially adopted the proposal for construction of a new dock basin separate from the river by a system of locks to regulate the water level. This began a lengthy period of planning and negotiations, with approval first being required from Westminster to give the corporation the powers to raise the necessary funds, estimated at half a million pounds. In 1883 the Ribble Navigation and Preston Dock Act was passed by parliament which allowed the corporation to divert the river and create a new basin, based on the plans drawn up by the engineer Edward Garlick. The Act also allowed the corporation to acquire the Dock Navigation Company and the Preston Dock Branch Line railway from the North Union Railway company in order to develop Preston as a major port.[1][2][18]

Construction began in 1884 and there was an enormous amount of work that had to be done. The river, which ran parallel to Strand Road and followed a course further north than its current location, was diverted so that the new dock basin could be created. A new channel was cut to the south, with a sharp bend taking the river westward from about opposite the old Victory Quay at Marsh lane, through the area known as Penwortham Marsh. The old section of river was dammed at both ends and the water pumped out. Excavation began on the site of the new shipping and tidal basins, with around five million cubic metres (180,000,000 cu ft) of earth, sand and rock removed, which was used to fill the old river bed to create the dock's northern quays. The new shipping basin was 12 metres (40 ft) deep, 910 metres (3,000 ft) long and 180 metres (600 ft) wide, with concrete walls and granite copings. Construction required the demolition of the old docks and a temporary wharf, "Diversion Quay", was built at the east end of the new river channel to allow trade to continue.[2]

The scope of he endeavour meant that the initial estimate of half a million pounds was soon exceeded and the corporation needed further funding of another equivalent amount to complete the project. Construction was delayed while approval was again sought from Westminster to raise the additional funds. This resulted in a long mortgage being taken out that would not be paid off by Preston's rate payers for over 60 years. Construction was also drawn out by several owners of Preston's textile mills, who, fearing the industries the new dock would attract would drive up the cost of labour, opposed the venture. They formed a political party, "The Party of Caution", and contested local elections with the aim of stopping public money being spent building the dock.[6][12]

On 21 May 1892 the concrete walls of a temporary dam built to hold back the Ribble were breached, allowing the basin to begin filling with water, and the new Port of Preston began operating a month later, with the official opening ceremony held on 25 June 1892. Initial facilities were at first limited, but the docklands railway was soon extended and new warehouses and cargo handling facilities were constructed as the volume of trade through the dock increased.[2]

Operation

_(14759108972).jpg.webp)

The new dock was not an immediate success, used by just four vessels in its first year of operation; however, by 1900 this number had grown to 170 and the future appeared rosy. The creation of the Preston Dock Branch Line railway in the 1840s, and later extensions in the 1890s and 1920s, allowed goods to be transported directly to and from ships, minimising loading and unloading times and providing the Port of Preston with a competitive advantage over other nearby ports.[6]

Over the course of its history the dock handled a wide variety of general cargoes. Incoming vessels would unload raw cotton, timber, china clay, fruit (including bananas and citrus from the West Indies), wheat, horses, cattle, coal, petroleum products, fishmeal, fertilisers, and wood pulp and esparto grass for paper making. Out-going vessels were mostly loaded with cotton products and other textiles from Preston's mills, and later manufactured goods from the town's growing industries. Pre-World War I saw a rise in popularity in excursion steamers operating from the docks providing day trips to nearby destinations, and post-World War II saw the introduction of passenger and vehicular ferry services to Northern Ireland. During both world wars the docks were used by the military for general wartime cargo and strategic operations, including the D-Day landings in 1944.

The dock's quayside facilities were developed to match the rising trade, originally handling bulk cargo but later upgraded to containerised service, the first dock in the UK to provide such a facility. Trade increased throughout the 1950s so much so that the charge for the port that had been levied on Preston residents’ rates bills since the opening of the dock was finally cancelled. Large quantities of fruit were being imported from the Windward and Leeward Islands; in one year the entire citrus crop from Dominica and Saint Lucia came through the port.[6]

The period 1960–1972 was the busiest in the dock's history, and peak volume was reached in 1968 when 2.5 million tons of trade passed through the port.[2] However, the Dockers Strikes of 1969 and 1970 severely disrupted the port's ferry services and deterred much of its foreign traffic and resulted in a noticeable fall in revenue, a trend that was not to be reversed.[2] The docks continued to experience a steady decrease in trade, including the abandonment of ferry services, and in 1975 the first serious financial trouble began after an operating loss of £1.5m, the largest in the port's history, was reported.[19]

Constant dredging of the Ribble proved a huge burden upon the port's revenue; in 1975 45% of the dock's income was spent on dredging operations.[2] A report to the then Preston Borough Council in September 1979 advised that there was no future prospect for operating the port at a profit and it was resolved that the docks should be closed and the area redeveloped.

Closure

Following a boom period in the 1960s Preston Dock suffered a series of financial setbacks in the early 1970s, which led to a record loss of £1.5 million in 1975, and each subsequent year of the decade recorded losses of between £800,000 and £1 million.[2]

As early as 1975 reports were produced looking into what could be done to stem the losses. However, the rising cost of operations and the decreasing revenues from diminishing trade[lower-alpha 4] led to the then Preston Borough Council deciding to close the port, and a phased closure was announced in 1976, which would result in the redundancy of 450 workers. However, a campaign to keep the port open, led by the public, newspapers, dockside workers, trade unions and local industry, gave the port a reprieve and the council applied for and received a grant of £2 million from Westminster for a two-year trial to revive the port's ailing fortunes. The council had still found no feasible solutions to the dock's inherent problems 18 months later, including a suggestion to redevelop the docks into a multi-functional estate creating an additional 1,500 jobs, which was rejected by the unions and local Labour councillors. With no further government funding available and facing the prospect of subsidising the dock at a cost of around a million pounds a year - a cost that Preston could not afford in a time of national economic downturn - in October 1979 the final decision was made to close the port in two years time.[19][20]

Closing the dock was not a straightforward procedure; a Private Members' Bill and an Act of Parliament would be required which would take about six months to prepare. Nor would it be cheap; it would require paying off outstanding debts and loans, and the payment of compensation including redundancy pay. The total cost was estimated at £3.5 million over 10 years, which would be recovered through the sale of the dock's assets and a levy imposed upon Preston's ratepayers. Assets identified for sale included cranes, dredgers and miscellaneous small vessels, pipelines and large fixtures, with an estimated value of £1.5 million.[2][19]

The Port of Preston was formally closed by the Preston Dock Closure Act on 31 October 1981, with the direct loss of 350 jobs.[2][20]

Redevelopment

In 1980 with the looming closure of the dock the Central Lancashire Development Corporation carried out a preliminary study, Preston Dock Redevelopment – Summary Report (1980), broadly proposing to redevelop over 150 hectares (380 acres) of the former docklands for mixed use (similar to the suggestion proposed but rejected when the dock's closure was first announced in 1976). However, their study identified a number of major constraints including polluted water and contaminated land, inadequacy of flood defences, and lack of infrastructure which would result in high costs of clearance and reclamation. The study also identified that for any redevelopment to be successful, a partnership between the council and private enterprise, would be necessary, and that funding was available from Westminster in accordance with the Derelict Land Grants scheme.[2]

The proposed name for the redeveloped site would be "Riversway", as it was to be mostly built on land that was the original course of the river, and the council began inviting bids from national and local consortia to produce detailed proposals for the redevelopment. Due to the size of the project and the associated constraints, the process was protracted and it was not until 1985 that a plan was finally chosen, submitted by Holder Mathias (Architects) of London and the Balfour Beatty corporation. The plan proposed that the former norther quayside would be redeveloped for retail use, the southern quayside for residential use, and the basin would feature a public marina. The area to the west of Riversway, tentatively referred to as "Riversway West", would be reserved for future commercial and light industrial use. The plan's general strategy was that the clearance, reclamation and infrastructure works would commence immediately to attract investment from the private sector to redevelop individual site. A condition of the proposal was that Balfour Beatty retained the development rights on the prime waterfront area north and east of the dock basin, in return for funding the road infrastructure project.[2]

The plan identified that the existing docklands railway along the north side of the basin occupied valuable development sites, and the railway would be diverted along the banks of the Ribble behind the dock's southern quay. This necessitated the construction of a 1,000-tonne (980-long-ton; 1,100-short-ton) swing bridge across the entrance to the lock which, to save money, had the railway tracks running down the centre of the roadway. Construction of the new infrastructure began in 1985 and generally proceeded from east to west, and continued until 1992.[2] New roads were constructed, including:

- 'Mariners Way', running parallel to Waters Lane along the basin's northern quayside, following the original course of the Ribble.

- 'Navigation Way', running parallel between the northern bank of the Ribble and the basin's southern quayside, across the new swing bridge on the western side of the basin and joining Mariners Way.

- 'Port Way', running east from Strand Road along the north bank of the Ribble (from about opposite the site of the 1820s port) and turning north along the eastern end of the basin to join Waters Lane, and providing access into Mariner's Way.

- 'Pedders Way', running from Waters Lane down to the western end of the basin, providing access to Mariners Way and Navigation Way, as well as to the existing industrial estate in Chain Caul Way.

- 'Channel Way', a smaller road running west from the A59 near Strand Road to provide east-bound traffic access to Riversway, it runs to the northern end of Port Way (also following the original course of the Ribble) to Strand Road, as well as providing access to a potential new business park to the east of Riversway.

Only four of the dock's original buildings[lower-alpha 5] were retained:[2]

- Shed No.3 on the south side of the basin, redeveloped for residential use as "Victoria Mansions"

- Customs House on Dock Road

- the office of Transport Ferry Service off Pedders Way (subsequently demolished for new development)

- the original Pump House building adjacent to the tidal basin (subsequently demolished for new development)

Following the opening of Riversway in July 1987,[22] over 2,000 jobs have been created from the opening of new and the relocation of exiting businesses. Subsequent development has seen the construction of residential areas commencing from 1989 and the new industrial zone to the west in 1992.[2]

Health hazards

Cyanobacteria

Since the dock's closure as a working port, the waters of the basin have suffered from frequent blooms of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria), which can be toxic to humans and animals. Despite repeated attempts to cure the problem and improve water quality, outbreaks still occur and are most prevalent in the warmer months, and signs are posted around the basin by the Preston City Council warning against swimming (including pets).[23][24]

Industrial waste

Redevelopment of the former docks saw the removal of land contaminated by industrial use. It was deemed that the most cost-effective solution was to create a purpose-made disposal area, licensed by the city's Waste Disposal Authority, on the river bank west of the main development. The contaminated soils were sealed in clay-lined containment cells and covered over, and the details recorded on a contaminated land register held by the council.[2]

In 2002–03 the council undertook an extensive investigation into soil and groundwater conditions at the site, and the basin and the river were sampled for any leakage from the containment cells. It was reported that no further remedial work was required to protect the Albert Edward Dock or the River Ribble due to low chemical concentrations. Furthermore, a cost-benefit analysis on the recovery of remaining hydrocarbons would have proved prohibitively expensive with little benefit to the environmental quality of the river. Therefore, in light of the findings and agreement with the Environment Agency this investigation was concluded.[25]

Historic facilities

Boat lock

Located at the western end of the Albert Edward Basin is the Bull Nose, a series of lock gates to maintain a constant water level within the basin and to provide ingress and egress for vessels to and from the River Ribble. The lock gates allow vessels up to 60 feet (18 m) in width to enter the basin. The gates are the original items installed when the docks were constructed in the 1880–1890s, and are made of Greenheart main timbers and Iroko planking. Each gate weighs 98 tons.[12]

The first single pair of gates separates the tidal basin from the River Ribble, to maintain a minimum operating depth in the tidal basin so that during low tide when the level of water in the river is too low to allow vessels to journey to the sea, they can remain in the tidal basin and not take up valuable berthing space along the docks. The main lock is two pairs of gates located on each end of a short canal, separating the tidal basin from the main shipping basin. When vessels enter the lock from the tidal basin, if the water level is lower than the level of the main basin, water is pumped in and once the inner gates are open the vessel can continue to the docks. When vessels enter the lock from the main basin, if the water level is higher than the level of the tidal basin, water is pumped out and once the outer gates are open the vessel can continue into the tidal basin. The lock limits vessels over approximately 200 metres (660 ft) from entering the main basin.

Following the closure of Preston Dock flood mitigation work commenced between 1982 and 1985 to stop flooding during severe storms and exceptionally high tides;[lower-alpha 6] the gates from the river to the tidal basin were repositioned and raised to a higher level so as to also act as storm gates, and flood banks were built along the river edge to a level of 8 metres (26 ft) above ordnance datum (AOD). During these works, all gates were refurbished, for which a large 100-tonne (110-ton) crane was constructed along the southern quayside near the lock, and in 1985 a new control tower building (which also controls the swing bridge) was opened, with operations overseen by the Preston City Council.[2]

The boat lock remains in operation to this day and provides access to the Preston Marina, which was built following redevelopment of the docks. The gates can open up to one hour before High Water (Liverpool) and remain open up to two hours after this time. Different opening timetables operate over summer and winter. Vessels arriving outside these hours can remain in the lay-by berth within the lock chamber, and await the next gate opening. The lock does not provide 24 hour operations; the control tower can be contacted on VHF Channel 16.[26]

Docklands Railway

_Preston_Docks_08.1968_(2)_(9859843804).jpg.webp)

In 1845 a railway line was built linking the old docks at Victoria Quay to Preston's main railway station[lower-alpha 7] Unlike many docks which utilise narrow-gauge tracks, Preston's dockland railway utilised standard gauge track, allowing freight to be routed directly to and from the main line without having to be transferred to different rolling stock. The line, officially known as the Preston Dock Branch Line, was originally operated by the North Union Railway until 1889, when ownership and operation transferred to the Preston Corporation. The corporation operated eight small tank locomotives which remained in service until 1968 when they were replaced by Sentinel diesel shunters, which remain in operation today with Ribble Rail, a subsidiary of the Ribble Steam railway, working bitumen trains. At the dock's peak the railway comprised around 43 kilometres (27 mi) of track, with multiple tracks and sidings running on both the north and south sides of the Albert Edward Basin. A marshalling yard, engine sheds and workshops were built at the western end of the docks on the northern shore of the Ribble, which is now the site of museum and workshops of the Ribble Steam Railway (RSR).[18]

The railway remained in operation after the docks' closure, with up to nine trains per week continuing to deliver petrol to the Petrofina petroleum storage tanks on Chain Caul Way (now part of the Anchorage Business park) until the company ceased operations at this site in 1992 and the facility was demolished. This left just one company, the Lancashire Tar Distillers (also located in what is now the Anchorage Business Park), still operating rail services, with three weekly freight trains delivering crude bitumen from the Lindsey Oil Refinery in Lincolnshire to the distilling plant, and empty trains returning to the Lincolnshire refinery from the Preston Docks.[lower-alpha 8] However, in 1995 the company switched to road transportation and the trains stopped until 2004, when the plant was sold to Total UK and rail operations recommenced.[2][27][18]

The redevelopment of the docks in the 1980s led to removal of much of the rail lines, but in 1985 a single line was built across the new Preston Docks swing bridge which ran along the north bank of the Ribble and rejoined the existing line near the level crossing on Strand Road. This section of the line is utilised by the RSR which operates regular trips on preserved rolling stock on weekends from April through to September, and special trains during the winter holiday season.[28]

Ferry services

In 1948 the Atlantic Steam Navigation company established a passenger and vehicular ferry service operating from the Preston Docks to Larne in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. The company utilised surplus World War Two military vessels known as Landing Ship, Tank (LST), to be the world' first commercial roll-on/roll-off ("RoRo") ferry service.[lower-alpha 9] The service, operating three times a week, proved an immediate success and in 1950 the company commenced a second service to Belfast.[29]

Atlantic Steam Navigation were nationalised in 1954, and operated under the trading names of 'Transport Ferry Service' and the 'Continental Line' and in 1957 the first of a number of new vessels, Bardic, came into service. This was the first purpose-built commercial RoRo ferry in the UK, and was soon followed by Doric and Ionic. The company also provided limited services to:[30]

Services were disrupted in a prolonged strike at the Preston Docks in 1969, and the company began looking for a new site to locate its operations. In 1973 the company moved its Larne service to its newly purchased site at Cairnryan (near Stranraer) in Scotland.[31] The Belfast service continued operating from Preston until its cancellation in 1975, signalling the end of scheduled ferry services from the Preston Docks.

Leisure excursions

The dock also provided berthing facilities for leisure traffic, with several paddle steamers offering day trips to several destinations including Merseyside, the Fydle coast, North Wales and the Isle of Man.

The Ribble Passenger Transport Co. had two vessels named Ribble Queen based in Preston. The original Ribble Queen was a twin-screw steamer built in 1903, which operated between 1903 and 1905. The second, Ribble Queen 2, was an older paddle steamer, the former PS Greenore built in 1896, which was purchased from the London and North Western Railway in 1922 and operated until 1925. These vessels provided excursion services to Southport and Liverpool but neither were successful.[32]

Excursion services to Blackpool was a far more popular route, especially during the Wakes Week holidays. The paddle steamer Nelson, built by the William Allsup shipyards in 1875 for the South Blackpool Jetty Co., operated to Blackpool's South Pier[33] Another company, the Blackpool Passenger Steamboat Co., which had the largest fleet of excursion vessels in Blackpool, provided trips to and from Blackpool's North Pier on the paddle steamer Greyhound from 1895 until the outbreak of the First World War, during which it served as a minesweeper.[34][35]

Another paddle steamer that operated out of Preston Dock was Bickerstaffe, also of the Blackpool Passenger Steamboat Co., which was used extensively during the 1911 railway strike to ferry passengers between Preston and Blackpool.[36] Like Greyhound, it was also pressed into service as minesweeper in World War I.[37]

Ship breaking

In 1894 the Sheffield industrialist Thomas W Ward opened his first ship breaking yard at Preston docks.[38] Ward had a contract with the Royal Navy and many former warships were broken up after the First World War, including the battleships HMS Dominion and HMS Hindustan, the cruisers HMS Skirmisher and HMS Sutlej and the destroyers HMS Nith and HMS Ribble. Merchant and passenger vessels broken up at the yard included SS Aleppo and RMS Etruria. Furniture, fittings and equipment removed from the ships would be traded at Ward's showroom in Sheffield. The weight of the ships' parts had been known to topple cranes, causing the death of a Preston worker in the 1950s.[39]

Demand for scrap fell in the 1960s and the yard faced increasing competition from breakers in India, Bangladesh and the Far East, which enjoyed the financial benefits of extremely low wages and lack of safety regulations, and Ward's business declined.[40] The yard ceased operating in 1970[41] with one of the last major vessels scrapped being the former Second World War destroyer HMS Holderness, which arrived for breaking on 20 November 1956.[42]

Ship building

.jpg.webp)

Following construction of the Victoria Quay, there was a boom in shipbuilding along the Ribble, with a number of shipyards constructed north and south of the new wharves.[43] The earliest known vessel constructed at these new yards was the paddle steamer Enterprise, launched in 1834 for the Mersey ferry service in Liverpool. The Preston Iron Shipbuilding Co. had a yard to the south of the quays, possibly operating from as early as 1845,[44] with eight vessels recorded as being built between 1865 and 1867.[45]

The most success of Preston's shipbuilders was William Allsop (as he was originally known). Allsop had been a millwright and engineer employed in the town's cotton trade and in 1854 entered into a partnership with a "Mr. Watson" to form the Calendonian Works. In 1873 Allsup (as he was now known) transferred title to his sons and the company became William Allsup & Sons Ltd Shipbuilders, Engineers and Iron Founders (no record can be found as to what became of Watson) and established three shipyards along the Ribble, specialising in vessels made from iron.[10] Records show at least 26 ships being built,[46] including the passenger steamer SS Toroa in 1899, which ran aground in 1916 off Babbit Island, Tasmania, Australia, with the loss of all hands.[47] In 1899 it was reported that Allsup's main yard was destroyed in a fire,[48] but the company continued to build vessels until at least 1902.[49]

The shipbuilding industry was not without its dangers. On 9 April 1884 during a launch of an iron steamer from the Allsup yards the supporting gear snapped and the vessel fell upon five workers; one was immediately killed, another died a few hours later and two more died the following day.[50] The sole survivor, a riveter named Holmes, was reported as being in a critical condition on 12 April, his fate thereafter unknown.[51]

Due to a shortage of steel during the First World War, land was leased from Preston Corporation in 1914 by the Hughes and Stirling Concrete Ship Yards for four slipways north of the Bull Nose for the construction of ferro-concrete ships. Orders were placed for ten 700-ton barges to transport iron ore to Britain from Spain. However, demand for the vessels fell following the cessation of hostilities and only two of the barges were completed and launched, Cretemanor (PD110) in September 1919 and Cretemoor (PD 112) in January 1920. The order for the other six vessels was cancelled but work had commenced on two further hulls which were abandoned, and they remained near the old slipways until the 1980s.[52] The site was then taken over by Mr H.C. Ritchie of Liverpool, who had developed the pre-cast construction method that the Hughes and Stirling yard used, operating as Ritchie Concrete Engineering and Shipbuilding Company.[53] The only record found for vessels constructed by the yard under this name was a small coaster Burscough but its life was very short; built in 1921, it was stripped of all salvageable metal parts in 1924 by the Preston shipbreakers Thos. W. Ward and its concrete hull towed to the Isle of Man where it was sunk and used as the foundation for a jetty.[54]

Other

Aside from facilities for the loading, unloading and temporary storage of general cargo and bulk cargo such as timber, the docks provided the following specialised infrastructure:[2]

- Bitumen distillation: In or around 1929 the Lancashire Tar Distillers company constructed a refinery for the distillation of bitumen, located off Chain Caul Way. In 2004 the company was sold to the petroleum company Total UK and the facility is still in use today. The docklands railways is still being utilised for the transport of crude bitumen to these facilities.

- Petroleum storage: In 1914 large oil and petroleum storage tanks were built in the north west area of the docklands, which were operated by Petrofino until the company ceased operations at this site in 1992, and the storage tanks were demolished. The docklands railway was utilised for the transport of petroleum to and from these facilities.

From October 1982 to November 1990 the former Isle of Man passenger vessel TSS Manxman was moored at Preston Dock. Originally purchased to be used as a museum and visitor centre, the vessel was converted for use as a floating restaurant and bar. Upon expiration of its mooring contract the vessel was towed to Liverpool.[55]

Further facilities included a hydraulic power house and a hospital.[2]

New facilities

Following the closure of the Port of Preston in 1981, the docks have been redeveloped and now provide the following facilities:

Anchorage Business Park

Developed from the original industrial estate located along Chain Caul Way to the west of Riversway is the Anchorage Business Park, named after the Preston's original mooring and wharves that dated back to pre-Industrial Revolution times. Also known as Riversway West, it is a business park with around twenty to thirty small to medium businesses and light industry, including:

- Booths Distribution and Manufacturing Centre

- Builders Supplies West Coast

- CEMEX Preston Concrete Plant

- Key Engineering and Hygiene Supplies

- Lustalux Ltd Window Film

- Makro Preston

- Marquis Motorhomes & Caravans Lancashire

- Ridecraft UK

- Total UK Ltd Bitumen Division

- The Vella Group Repair Centre

Further to the west are a number of car dealerships, including:

- Arnold Clark Preston Renault & Dacia

- Marshall Mercedes-Benz of Preston

- Preston Audi

- Simpsons Skoda Preston

- Vantage Toyota Preston

Preston Marina

A public marina, the Preston Marina, is located in the western end of Albert Edward Basin.[56]

Following closure of the docks, buoy moorings were installed in 1987 and operations as public marina began. In 1988–89 a building containing a cafe, chandlery and a ship broker was constructed, along with the installation of pontoon berths for 75 craft and a wave attenuator (floating shield) to protect moored vessels. In 1991, 26 additional pontoon berths were installed and a further 24 in 1992.[2] A dry storage and sales yard was built on the opposite side of Navigation Way, on the northeastern banks of the tidal basin.

An Italian cafe and bar, Baffito's, used to operate at the marina, but this closed in October 2019 following complaints of anti-social behaviour.[57] A fire broke out in the former premise in the early hours of 1 December 2020, badly damaging the building. Another fire broke out on 29 April 2021 causing further damage to the property, with arson suspected. On 17 June 2021 the damaged structure was demolished and the site - currently vacant as at November 2021 - is slated to become a care home.[58][59]

The marina is home to large numbers of a diverse range of sea birds, some of which nest in facilities specifically placed to encourage their breeding.[60]

Residential

Development of the residential area along the south of the basin began in 1989 when the council held a limited competition for architect and developer consortia for the construction of the dock's residential areas. The competition was won by a team of local architects, Brock Carmichael Associated, partnering with the Staffordshire development company Lovell Urban Renewal Ltd. Construction began in 1990 but the project was shelved after the first phase due to a recession in the housing market. The work was finally completed in 1995 by a subsidiary company, Lovell Housing, to a much modified version of the original concept more suited to the current market. The estate is known as Victoria Quay, after the early-1880s docks, and further street names continue the nautical theme adopted for the Riversway redevelopment.

Conversion of the former Shed No. 3 into Victoria Mansions was carried out by a Preston Company Tustin Developments, who also constructed the houses and flats immediately to the west. Further residential development commenced in 1997 with Wainhomes constructing 72 houses south of the tidal basin, along with Newfield Jones constructing a number flats and houses east of Victoria Mansions.[2]

Riversway Retail Park

The main feature of the Riversway redevelopment is a large retail park, Riversway, which was the first area within the former docklands to reopen in 1987. Located on the northern shore of the Albert Edward basin, it includes:

- Morrisons supermarket and petrol station

- Aldi supermarket to open in 2020, taking the old DFS store while DFS moves next door into the former Mothercare store.

- Halfords retail and auto centre

- Homebase home improvement and garden centre

- McDonald's fast-food restaurant

- Pets at Home pet store

- The Ribble Pilot, a Marston's pub and restaurant

- A Starbucks coffee shop.

- numerous home furnishings stores, including DFS and Bensons for Beds

At the northeastern end of the basin is a leisure and entertainment complex, with an Odeon cinema and a Chiquito Tex-Mex restaurant, and across Port Way is a Kentucky Fried Chicken fast food restaurant and a Fitness First gymnasium.

A number of car dealerships are located on the eastern fringe of Riversway along Port Way, including:

- Bowker BMW Preston

- Motordepot Car Supermarket

- Preston Motor Park, located on the opposite side of Port Way

Former Stores

- Mothercare baby and young children's products[lower-alpha 10]

Landmarks

Notable buildings

- Harbour House: located on the eastern end of the Albert Edward basin, Harbour House is the offices of a number of businesses including the Community Gateway Association, a non-profit organisation that provides public housing.[62]

- Lighthouse: while various navigation aids were located around the Preston Docks and along the Ribble, the lighthouse that stands in the Riversway Retail Park in front of the Morrisons supermarket is not a preserved feature of the old docks; it is a replica, built in 1986 after the docks closed to shipping. It was built by Morrison's to "guide shoppers to their new supermarket and to mark Preston's maritime past"[lower-alpha 11]

- Old Docks House: located at the intersection of Waters Lane and Port Way on the northeastern edge of Riversway, is Old Docks House. Built in 1936 in the Art Deco style and featuring a central clock tower, this building used to hold the offices of the Port of Preston. During the Second World War when Preston Dock was commandeered by the military, it was used as a marshalling post for the D-Day landings. More recently it has been used by telemarketing companies but is now serviced offices.[6]

Preserved features

A number of the dock's original features have been preserved, including:

- Buoys: large mooring buoys of varying sizes are located on the northern and southern docks at the western of the basin. Original navigation buoys are still in use in the basin.

- Loading crane: often mistaken for a crane that was used to load cargo onto vessels (these, along with other assets, were sold when the dock closed), this distinctive blue and orange crane was actually installed in 1958 to lift the lock gates. Large flotation devices were fitted to each side of a gate and the gate was floated out of its fittings and brought to the crane for lifting. The crane has a 100-tonne capacity and is still used today to lift vessels from the water.[12]

- 'Nelson' bell boat buoys: at the eastern and western entrances to the Riversway, are "bell boat buoys" which bear the name 'Nelson'. The boats' locations on Port Way and Pedders Ways mark the original course of River Ribble, which was diverted for the construction of the docks. The boat buoys, or more correctly, Nelson Safe Water Mooring and Landfall Buoys, were purchased by the Preston Corporation in 1890 from Irish Lights Commissioners and moored on the Ribble estuary off Lytham (where the dock's pilots were based) to mark the position of the "Nelson safe water" at the entrance to the Penfold Channel. The boats had a large bell that rang from the rocking of the waves and had lights powered by acetylene gas. In 1931, they were fitted with compressed carbon dioxide apparatus which enabled the bells to be automatically rung every half a minute, even in calm weather.[6][63]

Along the docks and nearby banks of the Ribble can be found old mooring facilities, and remnants of the old shipyards can be found near the site of the Preston Sea Cadets.

Wildlife

The dock basin is home to a variety of bird wildlife with ducks, coots and cormorants in residence. Swans and various gulls spend time on the dock and herons may be seen feeding nearby in the river. In 2010 members of the Fylde Bird Club installed a number of gravel-filled tyres and slate shelters on the pontoons at the Preston Marina to attract common terns and entice them to breed.[64] The project proved to a success and was followed by the club and local schools building over 170 breeding boxes to attract more birds. In 2017 it was reported that 130 pairs of common terns and four pairs of Arctic terns are nesting at the docks.[60]

Fish inhabiting the dock include eels and flounder, and freshwater species such as roach, chub and bream have been caught, as have sea trout and salmon.[2]

Activities and attractions

- The Preston Dragons are an amateur dragon boat racing club based at the Preston Marina

- The Ribble Steam Railway is located at the north-western end of the docks.

- Preston Docks Motocross (MX) is located off Wallend Road, approximately 1.7 km (1.1 mi) to the west of Preston Marina

- The Preston Guild Wheel is a 34 km (21 mi) walking and cycling route encircling Preston. Parts of the path follows the banks of the River Ribble and passes near the Preston Docks. It is a popular destination, especially in warmer weather, for local cyclists, joggers, dog-walkers and for those who enjoy a peaceful stroll.

- Annual regattas for pulling boats staged by the Preston Sea Cadets

- The banks of the Ribble at the Bull Nose has become a popular location for anglers

Appearances in media

- In 1982 the Preston Dock and TSS Manxman, then a floating restaurant moored in the basin, were the location of a TV commercial for American Express credit cards.[65]

See also

- Ships broken up at Preston

- Riversway (electoral ward)

Notes

- ↑ The course of the Moorbrook, also historically referred to as the Moor Brook, was interrupted during Preston's history in the 18th and 19th centuries. Prior to the construction of the Lancaster Canal in 1792-1797, the Moorbrook flowed westward from what is now the A6 North Road, following a course that ran parallel to Aqueduct Street and Waters Lane, then through the northern edge of an area known as Preston Marsh (located on northeast bank of the Ribble, around the junction of what is now Strand Road and Waters Lane) to enter the Ribble further west at Marsh End, just to the east of where Morrisons supermarket is now located on Mariners Way. On the opposite (i.e. southern) bank of the Ribble was an area known as Penwortham Marsh which would flood during spring tides, increasing the size of this "natural basin", and it was here on the river's northern bank that Preston's original wharves were located. The reclamation work and the construction of retaining walls by the Ribble Navigation Company in the mid 1800s stabilised the river's banks and diminished the size of this basin, but by then the New Quays had been built. The diversion of the Ribble in the 1880s for the construction of the Albert Edward Basin and the reclamation of land along the river's north shore for the new docks resulted in the Moorbrook - or what little of it by then remained - no longer flowing into the Ribble.[9]

- ↑ The Ribble has a number of channels, the main shipping channel being the Gut which runs 19 kilometres (12 mi) to the Ribble Estuary where it branches into a number of channels of varying depths into the Irish Sea. From 1850 these included the New (or South) Gut, listed with a depth of 6.7–8.8 metres (22–29 ft) at high-water, and the shallower Penfold Channel, listed at 5.5 metres (18 ft) at high-water.[11] For more information, refer Report on the Evolution of The Ribble Estuary

- ↑ Regarding metric measurements: Engineering Timelines reports the dock's dimensions as "914m long by 183m wide",[1] which converts to 2998.69 by 600.39 feet. However, original plans for the dock show Imperial measurements of 3000 by 600 feet; therefore any discrepancies in this or other conversions to metric should be ignored and the original Imperial measurements should be considered as canon.

- ↑ The number of ships visiting the port in 1975 was recorded at 675 but fell to 538 just one year later.[19]

- ↑ Some websites state that the lighthouse located in front of the Morrisons supermarket is an original from the Preston Docks; however, this is a replica constructed in 1986.[21]

- ↑ In 1977 a combination of high river levels and strong westerly winds blowing a high tide in to the Ribble estuary resulted in the flooding of large areas of the docklands.[2]

- ↑ Although only a little over a half mile in length, the docklands branch line posed some problems in its construction and operation. A steep-sided cutting and tunnel had to be dug under Fishergate and West Cliff Terrace and the new line was a rather sharp curve, which limited the wheelbase of the locomotives and wagons that could be used. The line was also quite steep, with a 1:29 gradient. This limited the weight of the trains, as they needed to be held under brakes down the hill, and locomotives required sufficient power to haul the trains up the hill (and the more powerful locomotives were usually the biggest, often too long for the sharply curving track). This was an on-going problem which limited freight operations until the 1990s, when a more modern class of locomotive was finally introduced.[27]

- ↑ The trains travel overnight from the refinery to Preston via Hebden Bridge in heated tankers which maintain the crude bitumen to between 160 and 180 °C (320 and 356 °F) to stop it from hardening. Prior to 1995 (when road transport was temporarily utilised) each train would normally comprise seven and occasionally up ten tankers, each with a loaded weight of 102 tonnes (100 long tons; 112 short tons), for a total haulage of around 700–1,000 tonnes (690–980 long tons; 770–1,100 short tons) per train. In 2004 when rail operations resumed the new 10-year contract upgraded the required amount of bitumen to 110,000 tonnes (110,000 long tons; 120,000 short tons) per annum; as a result the number of tankers increased to ten or twelve, for a total haulage of 1,000–1,200 tonnes (980–1,180 long tons; 1,100–1,300 short tons) per train. In 2010 a new design of tanker was introduced with an increased load capacity of 74 tonnes (73 long tons; 82 short tons) and able to hold the crude bitumen at a more constant temperature. A more powerful locomotive was brought into service, with each train now comprising fourteen or fifteen tankers for a total haulage of 1,400–1,500 tonnes (1,400–1,500 long tons; 1,500–1,700 short tons). The tankers are hauled by a main line locomotive to a siding off Port Way, where they are collected by a historic Sentinel diesel shunter (which previously operated on the docklands railways in the 1960s) and delivered to the processing plant on Chain Caul Way.[27]

- ↑ The company also utilised floating pontoons from the "Mulberry harbours" that the Allies built on the Normandy beaches for the D-Day landings of 1944, which the LSTs used to deliver their wartime cargo, to load vehicles onto these repurposed vessels.[6]

- ↑ This store closed in January 2020 after the company went into administration in November 2019.[61] As at 28 February 2020 this premise remains vacant.

- ↑ The Lancashire Evening Post in 1986 reported "The new lighthouse, strictly for landlubbers, was built from the ruins of the old port of Preston to steer shoppers in to the new Riversway store. The full scale model was intended to remind people of the city's maritime past and was intended for use in promotional activities and VIP visits."[21]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Albert Edward Dock". Engineering Timelines. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 "Port of Preston - History to 1981" (PDF). Preston City Council. February 2003. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ↑ "Collections - Archaeology". Harris Museum, Art Gallery & Library. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ↑ "Portmote". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- 1 2 "Preston Dock and Waterways History". Visit Preston. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Preston Dock Curiosities". Lancashire Past. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ↑ "About Preston Guild History". Visit Preston. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- 1 2 "Preston Dock". Preston Station Past and Present. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ↑ Information derived from various historic maps of Preston viewed at Harris Museum and Public Library, and from Lancashire County Council Maps and Related Information Online (MARIO). 26 February 2020.

- 1 2 David John Hindle (2014). Life In Victorian Preston. Gloucestershire UK: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781445619163.

- ↑ British Islands Pilot: The west coast of England and Wales, Volume 2. United States Hydrographic Office. 1917. ISBN 9781120167712.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ed Walker (23 June 2017). "Things you never knew about Preston Docks". Blog Preston. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ↑ Ed Walker (12 July 2014). "Preston's adopted navy ship HMS Charger at the Docks". Blog Preston. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ↑ Ed Walker (3 July 2014). "Riversway Festival cancelled for 2014". Blog Preston. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ↑ "Steam rail plan go-ahead". Lancashire Evening Post. 31 December 2011.

- ↑ "Railway Exploration Centre Gets The Green Light". Ribble Steam Railway and Museum. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ↑ Brian Ellis (17 November 2019). "Preston Dock clean-up 'all systems go'". Lancashire Evening Post. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- 1 2 3 "Ribble Steam Railway and Preston Docks". Ribble Steam Railway and Museum. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Imogen Cooper (2 November 2016). "How time was called on Preston Docks". Lancashire Evening post. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- 1 2 Ribble Steam Railway (12 August 2016). "Why did Preston port close?". Chuffs, Puffs & Whistles. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- 1 2 Thomas Nugent (19 October 2018). "SD5192: Lighthouse at Albert Edward Dock". Geograph UK. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ↑ Keith Johnson (2016). Preston in 50 Buildings. Gloucestershire, UK: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 9781445658971.

- ↑ "Visitor Information Albert Edward Basin". Preston City Council. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ↑ Brian Ellis (23 October 2019). "Locals launch bid to clean up water in Preston Dock". Lancashire Evening Post. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ↑ "Contaminated Land Strategy 2012" (PDF). Preston City Council. March 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ↑ "Lock gate operating times". Preston marina. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- 1 2 3 Ribble Steam Railway (3 November 2016). "Bitumen Trains – The Story So Far". Chuffs, Puffs and Whistles. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ↑ "Operating Days". Ribble Steam Railway and Museum. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ↑ "Former ferries of NI Pt.2: From Atlantic Steam Navigation to P&O". NI Ferry Site. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ↑ Atlantic Steam Navigation Company - Routes. Wikipedia. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ↑ "Larne Port - History". Port of Larne. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ↑ Ribble Steam Railway (27 July 2011). "Excursion Ships of the North West". The Ribble Pilot. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ↑ "Made in Preston - The Paddle Steamer 'Nelson'". Preston Digital Archive. 23 December 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ↑ Ian Boyle. "Excursion Ships of the North West". Simplon Postcards. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ↑ "PS Greyhound". paddlesteamers.info : The Internet's leading database of Paddle Steamers past and present. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ↑ "Paddle Steamer Bickerstaffe, Preston Docks c.1911". Preston Digital Archive. 29 November 2010. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ↑ "Exciting Excursions: Blackpool's Paddle Steamers". Fylde Coaster. 27 January 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ↑ Frank C Bowen, The Shipbreaking Industry, retrieved 24 February 2020

- ↑ Ribble Steam (13 October 2013). "Preston Dock – Shipbreakers". Chuffs, Puffs and Whistles. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ↑ "Shipbreaking at Preston, Barrow and Morecambe". National Museums Liverpool. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ↑ Andrew Marland (22 November 2016). "#464 – Shipbreaking in Morecambe". Mechanical Landscapes. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ↑ Mike Critchley (1982). British Warships Since 1945 Part 3: Destroyers. Maritime Books UK. ISBN 9780950632391.

- ↑ Map of Preston (Offline, Harris Museum and Library, Preston. 26 February 2020). 1:10,560. Cartography by J. Harkness. Guardian Office, Preston. 1865.

- ↑ Map of Preston (Offline, Harris Museum and Library, Preston. 26 February 2020). 1:10,560. Cartography by J. Rapkin. Literary and Philosophical Institution, Preston. 1845.

- ↑ "Vessel List (Preston)". Shipping and Shipbuilding. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ↑ "Alsupp and Sons". Grace's Guide to British History. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ↑ "Daily Telegraph (Launceston, TAS) Tuesday 16 May 1916". National Library of Australia. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ↑ Cheltenham Chronicle, 4 March 1899

- ↑ "Vessel List (Preston)". Shipping and Shipbuilding. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ↑ Shields Daily Gazette, 10 April 1884

- ↑ Worcestershire Chronicle, 12 April 1884

- ↑ "Hughes and Stirling Concrete Ship Yards, Preston Dock c.1920". Preston Digital Archive. 2 September 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ↑ "Hughes and Stirling Concrete Ship Yards, Preston Dock c.1920". Preston Digital Archive. 22 September 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ↑ "Concrete Coaster 'Burscough' at T.W. Wards Shipbreaking Yard, Preston 1924". Preston Digital Archive. 27 November 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ↑ Paul Brown (2010). Historic Ships: The Survivors. Amberley Publishing, Gloucestershire UK. ISBN 9781848689947.

- ↑ "Preston Marina". Preston Marina. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ↑ Olivia Baron (2 October 2019). "Baffito's at Preston Docks has closed amid reports of anti-social behaviour". Lancs Live. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ↑ Abigail Donoghue (1 December 2020). "New pictures show aftermath of fire at former Baffito's restaurant at Preston Docks". Blog Preston. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ↑ Danielle Kate Wroe (17 June 2021). "Former Baffito's restaurant pulled down to make way for care home". Blog Preston. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- 1 2 Paul Ellis. "A seabird colony in a city. Preston's tern colony, Lancashire England". The Urban Birder World. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ↑ Elias Jahshan (8 November 2019). "2800 jobs affected, 79 stores to shut as Mothercare falls into administration". Retail Gazette. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ↑ "Community gateway - Who We Are". Community Gateway Association. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- ↑ "New Life For Historic Buoys". Maritime Journal (). 21 May 2010. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ↑ "Preston Docks Common Terns". Fylde Bird Club Lancashire. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ↑ "1982 Lancashire nostalgia: A Preston film, £1,850 undies and a gravy dress". The Burnley Express. 1 November 2018. Retrieved 28 February 2020.