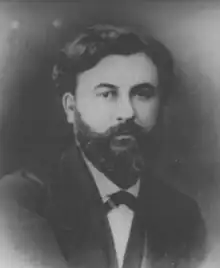

Émile Reynaud | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 8 December 1844 Montreuil, Seine-Saint-Denis, France |

| Died | 9 January 1918 (aged 73) |

Charles-Émile Reynaud (8 December 1844 – 9 January 1918) was a French inventor, responsible for the praxinoscope (an animation device patented in 1877 that improved on the zoetrope) and was responsible for the first projected animated films. His Pantomimes Lumineuses premiered on 28 October 1892 in Paris. His Théâtre Optique film system, patented in 1888, is also notable as the first known instance of film perforations being used. The performances predated Auguste and Louis Lumière's first paid public screening of the cinematographe on 26 December 1895, often seen as the birth of cinema.

Early life

Charles-Émile Reynaud was born in Montreuil, Seine-Saint-Denis, on 8 December 1844, to Brutus Reynaud, an engineer who moved to Paris from Le Puy-en-Velay in 1842, and Marie-Caroline Bellanger, a former schoolteacher who educated Émile at home.[1][2] Marie-Caroline was trained in watercolor painting by Pierre-Joseph Redouté and taught her son drawing and painting techniques. By 1862 he started his own career as a photographer in Paris.[3][4]

Reynaud constructed steam engines at age 13. He worked as an apprentice for Antoine Samuel Adam-Salomon. At age 19 he met François-Napoléon-Marie Moigno at one of Moigno's lectures and became his assistant. Brutus died in 1865, and the Reynaud family moved to Le Puy-en-Velay. Reynaud was taught Latin, Greek, physics, chemistry, mechanics, and natural sciences by his uncle, a doctor in the area. He was a nurse during the Franco-Prussian War. [1][5]

Career

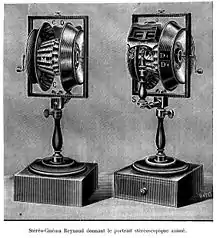

Reynaud started holding free magic lantern shows similar to Moigno's in December 1873. He created the praxinoscope out of a cookie box after reading a series of 1876 articles in La Nature about optical illusion devices. He patented it in 1877, and received a honourable mention at the 1878 Exposition Universelle. He started production on the device and was able to quit his teaching job after its financial success after initially being offered at Le Bon Marché stores. Ernest Meissonier displayed Eadweard Muybridge's The Horse in Motion using a praxinoscope in 1882.[6][7]

Reynaud's son Paul stated that his father's inspiration for the Théâtre Optique came after seeing a penny-farthing. The system was displayed at the 1889 Exposition Universelle. He filed a patent on 1 December 1888, and it was issued on 14 January 1889. He received a patent for it in the United Kingdom on 8 February. He signed a contract with the Musée Grévin on 11 October 1892, and its first regular public screenings started on 28 October. The first showing included screenings of Un bon bock, Le Clown et ses chiens, and Pauvre Pierrot. Un Rêve au coin du feu was shown from December 1894 to July 1897, and Autour d'une cabine from December 1894 to March 1900.[8][9][10]

Reynaud received 500 francs (equivalent to $1,465,911 in 2022) per month and 10% of the box office. The contract disadvantaged Reynaud as he paid for the maintenance of the system and was required to oversee all of the daily showings.[11][9] He closed the theatre from 28 February 1894 to 1 January 1895, and instead had a magician perform so that he could improve his equipment.[12] In 1895, Arthur Meyer, the owner of the Musée Grévin, demanded that Reynaud produce more films, which he painted himself. He created the photo-scénographe, a version of the théâtre optique that could take photographs, in 1895, but it was overshadowed by the cinematograph of Auguste and Louis Lumière.[13] Reynaud estimated that the 12,000 showings were attended by a total of 500,000 people.[14]

Reynaud hired George Foottit and Chocolat to perform a William Tell routine at Parc de Saint-Cloud and recorded them using the photo-scénographe in April 1896. He hand-colored the frames and showed the film from August 1896 to March 1900. A film using Félix Galipaux was shown from July 1897 to December 1898. However, the success of other filmmakers reduce the popularity of Reynaud's showings and they ended on 1 March 1900. He destroyed the théâtre optique during a fit of despair and years later he threw most of his films into the Siene. However, his son preserved Autour d'une cabine and Pauvre Pierrot. Léon Gaumont wanted to purchase the théâtre optique from Reynaud and donate it to a museum, but it was already destroyed.[13]

Reynaud patented the stéréo-cinéma, a stereo camera that could take 3D film, on 16 October 1902. He made several films with the camera, but was unable to find financial backing.[13]

Personal life

Reynaud married Marguerite Rémiatte, with whom he had two sons, on 21 October 1879.[15] During World War I he lived in hospitals and nursing homes before dying on 9 January 1918.[13]

Legacy

Henri Langlois convinced Reynaud's son to donate surviving praxinoscopes and Autour d'une cabine to the Cinémathèque Française in the 1930s. Langlois reconstructed the théâtre optique for the opening of the Musée de la Cinémathèque in 1972. Julien Pappé restored Pauvre Pierrot in 1981, and Autour d'une cabine was transferred to 35mm film in 1985.[16]

Filmography

The 5 Pantomimes Lumineuses were painted directly onto a transparent strip of images of shellac protected gelatin and manipulated by hand to create an approximately 15 minute show comprising approximately 500 images per title. The three Photo-peintures animées (animated photo-paintings) were directed with the Photo-Scénographe, a camera inspired by the Chronophotographe à bande mobile of Étienne-Jules Marey.

| Release year | Date | Film | Images | Length | Duration | Actors | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28 October 1892 | 1888 | Un bon bock | 700 | 50 m | 15 mn | few images preserved | |

| 1890 | Clown et ses chiens | 300 | 22 m | c. 10 mn | lost | ||

| 1891 | Pauvre Pierrot | 500 | 36 m | c. 15 mn | all preserved | ||

| December 1894 | 1893 | Autour d'une cabine | 636 | 45 m | c. 15 mn | preserved | |

| 1893 | Un Rêve au coin du feu | 400 | 29 m | c. 12 mn | lost | ||

| Photo-peintures animées | |||||||

| 1896 | 1896 | Guillaume Tell | Clowns Footit and Chocolat | few images preserved | |||

| 1897 | 1896 | Le Premier cigare | Félix Galipaux | ||||

| Not released | 1898 | Les Clowns Price | Clowns Price of the Alhambra |

- The two preserved short animated films

- Video of Pauvre Pierrot, the first preserved animated cartoon, 1891

- Autour D'une Cabine, from 1894, one of the first animated films

Autour d'une cabine

Autour d'une cabine

Praxinoscope strips (1877–1879)

- La Rosace Magique

- Le Trapèze

- Le singe musicien

- Le fumeur

Series 1

- L'Aquarium

- Le Jongleur

- L'Équilibriste

- Le Repas des Poulets

- Les Bulles de Savon

- Le Rotisseur

- La Danse sur la Corde

- Les Chiens Savants

- Le Jeu de Corde

- Zim, Boum, Boum

Series 2

- Les Scieurs de Long

- Le Jeu du Volant

- Le Moulin à Eau

- Le Déjeuner de Bébé

- La Rosace Magique

- Les Papillons

- Le Trapèze

- La Nageuse

- Le Singe Musicien

- La Glissade

Series 3

- La Charmeuse

- La Balançoire

- L'Hercule

- Les Deux Espiègles

- Le Fumeur

- Le Jeu de grâces

- L'Amazone

- Le Steeple-chase

- Les Petits valseurs

- Les Clowns

Inventions

- The praxinoscope, 1876

- The praxinoscope-jouet (toy praxinoscope), 1877

- The praxinoscope-théâtre, 1879

- The projecting praxinoscope, 1880

- Image bands with central perforation.

- The Théâtre Optique, 1888

- The stéréo-cinéma (animations in 3D), 1907

Books and references

References

- 1 2 Bendazzi 1994, p. 3.

- ↑ Myrent 1989, p. 191.

- ↑ "Biographie".

- ↑ Myrent 1989.

- ↑ Myrent 1989, p. 191-192.

- ↑ Bendazzi 1994, p. 4.

- ↑ Myrent 1989, p. 192-193.

- ↑ Myrent 1989, p. 193; 195-198.

- 1 2 Bendazzi 1994, p. 5.

- ↑ Rossell 1995, p. 119.

- ↑ Myrent 1989, p. 196.

- ↑ Rossell 1995, p. 131.

- 1 2 3 4 Myrent 1989, p. 199.

- ↑ Myrent 1989, p. 202.

- ↑ Myrent 1989, p. 193.

- ↑ Myrent 1989, p. 200.

Works cited

- Bendazzi, Giannalberto (1994). Cartoons: One hundred years of cinema animation. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253209374.

- Myrent, Glenn (1989). "Emile Reynaud: First Motion Picture Cartoonist". Film History. Indiana University Press. 3 (3): 191–202. doi:10.2307/3814977. JSTOR 3814977.

- Rossell, Deac (1995). "A Chronology of Cinema, 1889-1896". Film History. Indiana University Press. 7 (2): 115–236. doi:10.2307/3815166. JSTOR 3815166.