Raimundo Díaz Pacheco | |

|---|---|

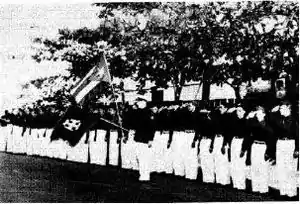

Raimundo Díaz Pacheco commanding the Cadets of the Republic | |

| Born | 1906 Carraízo, Trujillo Alto, Puerto Rico |

| Died | October 30, 1950 San Juan, Puerto Rico |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1924–1950 |

| Rank | Comandante (Commander) |

| Commands held | Cadets of the Republic (Puerto Rico) * Treasurer General of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party |

| Battles/wars | Puerto Rican Nationalist Party revolts of the 1950s *San Juan Nationalist revolt |

| Part of a series on the |

| Puerto Rican Nationalist Party |

|---|

|

Raimundo Díaz Pacheco [note 1] (1906 - October 30, 1950) was a political activist and the Treasurer General of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. He was also commander-in-chief of the Cadets of the Republic, the official youth organization within the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party. This quasi-military organization was also known as the Ejército Libertador de Puerto Rico (The Liberation Army of Puerto Rico).

On October 30, 1950, a series of revolts occurred in scattered locations in Puerto Rico in opposition to U.S. colonial rule. These were known as the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party revolts. On that day of October 30, Díaz Pacheco led an armed attack on La Fortaleza, the residence of the Governor of Puerto Rico in San Juan, with the intent to assassinate Governor Luis Muñoz Marín. Díaz Pacheco was shot dead in the unsuccessful attempt.

Early years

Díaz Pacheco was born in the barrio of Carraízo in the municipality of Trujillo Alto, Puerto Rico, where he received his primary and secondary education. Díaz Pacheco and his five siblings were believers in the cause of Puerto Rican independence and, in 1924, joined the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico.[1]

1924 was also the year that Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos joined the party and was named vice-president. By 1930, there were disagreements between José Coll y Cuchí, founder of the Nationalist Party, and Albizu Campos as to how the party should be run. Coll y Cuchi and his followers abandoned the party and on May 11, 1930, Albizu Campos was elected president.

Under Albizu Campos's leadership during the years of the Great Depression, the party became the largest independence movement in Puerto Rico. However, by the mid-1930s, after disappointing electoral results and strong repression by the territorial police authorities, Albizu Campos opted against electoral participation and advocated direct, violent revolution.[1]

Cadets of the Republic

In the 1920s, there was a non-political student organization in the University of Puerto Rico called Patriotas Jovenes (Young Patriots). By the 1930s, the members of this organization were influenced by the teachings of Albizu Campos. They adopted the Nationalist Party's independence ideals, and dismissed any student who would not swear allegiance to them. The organization was renamed Cadetes de la Republica (Cadets of the Republic) and Joaquin Rodriguez, a Nationalist, was placed in charge.[1]

Díaz Pacheco and his brother Faustino were active members of the cadets. The organization became the official youth branch of the Nationalist Party. In accordance with the beliefs of Albizu Campos, organization and discipline were considered the keys to victory, in the struggle for Puerto Rico's independence. Cadets were required to wear a uniform of white pants and gloves, and everything else - the shirt, tie, belt, boots, military cap - was black. Officers wore a white jacket over the black shirt and tie, and a white officer's cap.

The cadets were divided into companies, each of which represented a different town in Puerto Rico. They were all required to participate in local and national acts, such as the celebration of José de Diego's birthday. All of the cadets received military training which included marching, field tactics, self-defense and survival.[1]

Ponce massacre

On April 3, 1936, a Federal Grand Jury submitted accusations against Pedro Albizu Campos, Juan Antonio Corretjer, Luis F. Velázquez, Clemente Soto Vélez, Erasmo Velázquez, Julio H. Velázquez, Rafael Ortiz Pacheco, Juan Gallardo Santiago, and Pablo Rosado Ortiz. They were charged with sedition and other violations of Title 18 of the United States Code.[2] Title 18 of the United States Code is the criminal and penal code of the federal government of the United States. It deals with federal crimes and criminal procedure.[3]

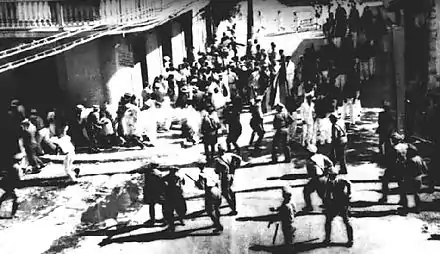

The photo was sent to U.S. Congress.[4]

On March 21, 1937, a Palm Sunday, the cadets were to participate in a peaceful march scheduled in the city of Ponce. The march had been organized by the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party to commemorate the ending of slavery in Puerto Rico by the governing Spanish National Assembly in 1873. The march was also protesting the imprisonment, by the U.S. government, of Nationalist leader Albizu Campos on alleged sedition charges.[5][6] Díaz Pacheco, who by then was the Comandante (Commander) of the Cadets of the Republic, and his brother Faustino were present when this peaceful march turned into the bloody police slaughter, which became known as the Ponce massacre.

Several days before the scheduled Palm Sunday march, the organizers received legal permits for a peaceful protest from José Tormos Diego, the mayor of Ponce. However, upon learning of the planned protest, the colonial governor of Puerto Rico General Blanton Winship, who had been appointed by US president Franklin D. Roosevelt, demanded the immediate withdrawal of the permits.[7]

Without notice to the organizers, or any opportunity to appeal, or any time to arrange an alternate venue, the permits were abruptly withdrawn just before the protest was scheduled to begin.[7]

As La Borinqueña, Puerto Rico's national song, was being played, the demonstrators - which included the cadets, led by Tomás López de Victoria, the Captain of the Ponce branch and the women's branch of the Nationalist Party known as the Hijas de la Libertad (Daughters of Freedom) - began to march.[8] Empowered by the North American police chief, and encouraged by the governor, the police fired for over 15 minutes from four different positions. They fired with impunity on the cadets and bystanders alike - killing men, women and children.[7]

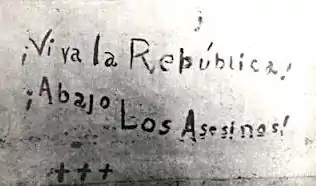

The flag-bearer of the cadets was shot and killed during the massacre. A young girl by the name of Carmen Fernández proceeded to take the flag, but was shot and gravely injured. A young cadet by the name of Bolívar Márquez, despite being mortally wounded, dragged himself to a wall and wrote with his blood the following message before he succumbed to his wounds:

"¡Viva la República, Abajo los asesinos!"

("Long live the Republic, Down with the Murderers!")

Nineteen people were killed, and about 235 were wounded.[7] The dead included 17 men, one woman, and a seven-year-old girl. Some of the dead were demonstrators, while others were simply passers-by. Many were chased by the police and shot or clubbed at the entrance of their houses as they tried to escape. Others were taken from their hiding places and killed. Leopold Tormes, a member of the Puerto Rico legislature, told reporters how a policeman murdered a nationalist with his bare hands. Dr. José N. Gándara, one of the physicians who assisted the wounded, testified that wounded people running away were shot, and that many were again wounded by the clubs and bare fists of the police. No arms were found in the hands of the civilians wounded, nor on the dead ones. About 150 of the demonstrators were arrested immediately afterward; they were later released on bail.[7]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

On June 7, 1937, Albizu Campos and the other leaders of the Nationalist Party were transferred to the Federal Penitentiary in Atlanta, by order of federal judge Robert A. Cooper. The next day, Díaz Pacheco participated in an assassination attempt on Judge Cooper, in retaliation for Cooper's rigging the jury with ten North Americans and only two Puerto Ricans,[10] and for sentencing the Nationalist leadership to long prison terms.[2] Díaz Pacheco together with nine other Nationalists were arrested and accused of attempting against the life of Judge Cooper. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt became involved when on October 22, 1937, he signed Executive Order Number 7731 designating Martin Travieso, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico, to perform and discharge the duties of Judge of the District Court of the United States for Puerto Rico in the trial against the Nationalists. Thereby, permitting judge Cooper to serve as a Government witness.[11] Díaz Pacheco and his comrades were found guilty of the charges against them and were imprisoned.[1]

Puerto Rico's Gag Law (Law 53)

After Díaz Pacheco was released from prison, he resumed his role as Commander of the Cadets. Unbeknownst to him, his brother Faustino had abandoned the Nationalist Party in 1939, and had turned into an informant for the FBI.[1]

Albizu Campos returned to Puerto Rico in 1947, after having been incarcerated for 10 years in Atlanta. Díaz Pacheco and the cadets were among those who greeted him. Albizu Campos named Díaz Pacheco Treasurer General of the party. Thus, Díaz Pacheco now served as both Comandante (Commander) of the Cadets of the Republic, and as Treasurer General of the party. As Treasurer General he was responsible for all the funds received by the municipal treasurers of the party.[1]

On May 21, 1948, the Puerto Rican legislature, which was presided over by Luis Muñoz Marín approved Law 53. The law which is also known as Ley de la Mordaza or "Puerto Rico's Gag Law" was signed into law on June 10, 1948 by the U.S.- appointed governor Jesús T. Piñero. The law's main objective was to suppress the independence movement in Puerto Rico. The law made it a crime to own or display a Puerto Rican flag, to sing a patriotic tune, to speak or write of independence, or meet with anyone, or hold any assembly, with regard to the political status of Puerto Rico.[12] [13]

Puerto Rican Nationalist Party revolts of the 1950s

Various incidents between the government and the party led to call for an armed revolt by the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party against United States Government rule over Puerto Rico.

The revolts specifically repudiated the so-called "Free Associated State" (Estado Libre Asociado) designation of Puerto Rico - a designation that the nationalist considered a colonial farce.

The revolts began on October 30, 1950, upon the orders of Nationalist leader Albizu Campos, with uprisings in various towns, among them Peñuelas, Mayagüez, Naranjito, Arecibo and Ponce. The most notable uprisings occurred in Utuado, Jayuya, and San Juan, Puerto Rico.[14] [15]

San Juan Nationalist revolt

Díaz Pacheco was in charge of the San Juan revolt. The objective of the revolt was to assassinate the Governor of Puerto Rico Luis Muñoz Marín, at his residence La Fortaleza. [15]

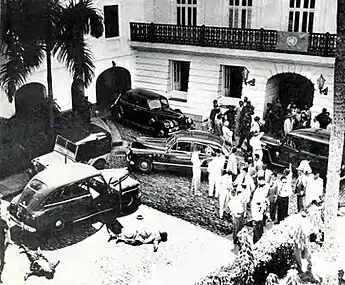

Early in the morning of October 30, Nationalists Domingo Hiraldo Resto, Carlos Hiraldo Resto, Gregorio Hernández and Manuel Torres Medina met at the house of Díaz Pacheco, in the San Juan sector of Martín Peña. At 11 A.M., they boarded a green Plymouth and headed towards Old San Juan. The men arrived at La Fortaleza at noon and stopped their car 25 feet from their objective's main entrance[16] They got out of the car with a submachine gun and pistols in hand and immediately began firing at the mansion. Díaz Pacheco headed towards the mansion while the others took cover close to their car, and fired pistols from their positions.

The Fortaleza guards and police, who knew of the planned attack thanks to a double agent named E. Rivera Orellana, were already in defensive positions and returned fire.[17]

Díaz Pacheco aimed his sub machine gun fire at the second floor of the mansion, where the executive offices of Governor Muñoz Marín were located. During the firefight Díaz Pacheco wounded two police officers, Isidoro Ramos and Vicente Otero Díaz, before he was killed by Fortaleza guard Carmelo Dávila.[16]

Meanwhile, the police continued to fire upon the other Nationalists. Domingo Hiraldo Resto was seriously wounded, but despite his wounds he dragged himself towards the mansions entrance. He was able to reach the mansions main door and once there he was motionless and appeared to be dead. He suddenly turned and sat on the steps and with his hands held up pleaded for mercy, his pleas however, were answered with a fusillade of gunfire.[17]

| External audio | |

|---|---|

Hernández, who was also severely wounded, continued firing at the police from under his car. A police officer and a detective from La Fortaleza with submachine guns approached the car and fired upon Hernández, Carlos Hiraldo Resto and Torres Medina. Both Carlos Hiraldo Resto and Torres Medina were killed, and their motionless bodies were by the right side of the car.

Hernández was believed to be dead, however he wasn't, and he was taken to the local hospital along with the wounded police officers where they were operated on for their respective wounds. The battle lasted 15 minutes and at the end of the battle there were five nationalist casualties (four dead and one wounded) plus three wounded police officers.[17]

E. Rivera Orellana, a sixth "Nationalist" who later turned out to be an undercover agent, was arrested near La Fortaleza and later released.[17]

Aftermath

The revolt failed because of the overwhelming force used by the US military and Puerto Rican police forces against the Nationalists. Hundreds of Nationalists were arrested and the party was never the same. Law 53, the Gag Law (or La Ley de la Mordaza as it is known in Puerto Rico), was repealed in 1957. In 1964, David M. Helfeld wrote in his article Discrimination for Political Beliefs and Associations that Law 53 was written with the explicit intent of eliminating the leaders of the Nationalist and other pro-independence movements, and to intimidate anyone who might follow them - even if their speeches were reasonable and orderly, and their activities were peaceful.[18]

Betrayal by his own brother

According to the FBI Files: Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico (1952),[19] Díaz Pacheco's brother Faustino (1903–2003) cooperated with the FBI, and was one of their primary informants regarding the Nationalist Party, the Cadets of the Republic, and the entire Puerto Rican revolution.

For nearly twenty years, Faustino Díaz Pacheco provided the FBI with detailed information about the structure, funding, leadership, weapons, recruitment activity, and strategic planning of the Nationalist Party and the Cadets of the Republic. In providing the FBI this information Faustino betrayed his own brother, the Nationalist movement, and the people of Puerto Rico.[1]

Further reading

- El Ataque Nacionalista a La Fortaleza (Spanish); author; Gregorio Hernandez Rivera; Publisher: Publicaciones Rene (January 2007); ISBN 978-1-931702-01-0

- America's Colony: The Political and Cultural Conflict between the United States and Puerto Rico (Critical America (New York University Hardcover)); author: Pedro A Malavet; Publisher: NYU Press; ISBN 978-0-8147-5680-5

- War Against All Puerto Ricans: Revolution and Terror in America’s Colony; Author: Nelson Antonio Denis; Publisher: Nation Books (April 7, 2015); ISBN 978-1568585017.

See also

19th Century male leaders of the Puerto Rican Independence Movement

- Ramón Emeterio Betances

- Mathias Brugman

- Francisco Ramírez Medina

- Manuel Rojas

- Segundo Ruiz Belvis

- Antonio Valero de Bernabé

19th century female leaders of the Puerto Rican Independence Movement

Male members of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party

- Pedro Albizu Campos

- José S. Alegría

- Casimiro Berenguer

- Rafael Cancel Miranda

- José Coll y Cuchí

- Oscar Collazo

- Juan Antonio Corretjer

- Carmelo Delgado Delgado

- Tomás López de Victoria

- Hugo Margenat

- Francisco Matos Paoli

- Vidal Santiago Díaz

- Daniel Santos

- Clemente Soto Vélez

- Griselio Torresola

- Antonio Vélez Alvarado

- Carlos Vélez Rieckehoff

- Teófilo Villavicencio Marxuach

Female members of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party

- Julia de Burgos

- Blanca Canales

- Rosa Collazo

- Lolita Lebrón

- Isabel Rosado

- Isabel Freire de Matos

- Ruth Mary Reynolds

- Isolina Rondón

- Olga Viscal Garriga

Articles related to the Puerto Rican Independence Movement

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "FBI Files"; "Puerto Rico Nationalist Party"; SJ 100-3; Vol. 23; pages 104-134. Archived 2013-11-01 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 FBI Files on Puerto Ricans Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ [*text of Title 18 Chapter 601 Immunity for witnesses, via findlaw.com]

- ↑ "La Masacre de Ponce" (in Spanish). Proyecto Salón Hogar. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- ↑ Latino Americans and political participation. ABC-CLIO. 2004. ISBN 1-85109-523-3. Retrieved 2009-05-01.

- ↑ "Latino Americans and Political Participation: A Reference Handbook". By Sharon Ann Navarro and Armando Xavier Mejia. 2004. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC–CLIO, Inc. ISBN 978-1-85109-523-0

- 1 2 3 4 5 The Puerto Rican diaspora. Temple University Press. 2005. pp. 76. ISBN 1-59213-413-0.

- ↑ Luis Muñoz Marín: Puerto Rico's democratic revolution. Editorial UPR. 2006. p. 152. ISBN 0-8477-0158-1.

- ↑ The Ponce Massacre, why is it important to remember? Archived 2013-06-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Albizu Campos: Puerto Rican Revolutiionary; Federico Ribes Tovar (1971); p. 64

- ↑ Executive Order 7731 - DESIGNATING THE HONORABLE MARTIN TRAVIESO AS ACTING JUDGE OF THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES FOR PUERTO RICO FOR THE TRIAL OF THE CASE OF UNITED STATES v. JULIO PINTO GANDIA, ET AL

- ↑ "Jaime Benítez y la autonomía universitaria"; by: Mary Frances Gallart; Publisher: CreateSpace; ISBN 1-4611-3699-7; ISBN 978-1-4611-3699-6

- ↑ Ley Núm. 282 del año 2006

- ↑ Law Library Microform Consortium Archived 2010-12-14 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 "El ataque Nacionalista a La Fortaleza"; by Pedro Aponte Vázquez; Page 2; Publisher: Publicaciones RENÉ; ISBN 978-1-931702-01-0

- 1 2 "El ataque Nacionalista a La Fortaleza"; by Pedro Aponte Vázquez; Page 4; Publisher: Publicaciones RENÉ; ISBN 978-1-931702-01-0

- 1 2 3 4 El ataque Nacionalista a La Fortaleza; by Pedro Aponte Vázquez; Page 7; Publisher: Publicaciones RENÉ; ISBN 978-1-931702-01-0

- ↑ "Discrimination for Political Beliefs and Associations"; Helfeld, D. M.; Revista del Colegio de Abogados de Puerto Rico; volumen = 25

- ↑ FBI Files: Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico (1952); SJ 100-3; Vol. 23; pp. 103-121; released under the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA); Title 5, U.S. Code, Section 522