| Battle of Haldighati | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Mughal–Rajput Wars | |||||||||

Painting of the traditional account of the battle by Chokha of Devgarh, 1822 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

3,000 cavalry 400 Bhil archers Unknown number of elephants |

10,000 men Unknown number of elephants | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

500 dead (According to Abul Fazl) 1,600 dead or wounded (Mewari sources) | 150 dead (According to Abul Fazl) | ||||||||

| Badayuni who was present in the battle says that 500 men were killed from both sides, of which 120 were Muslims. | |||||||||

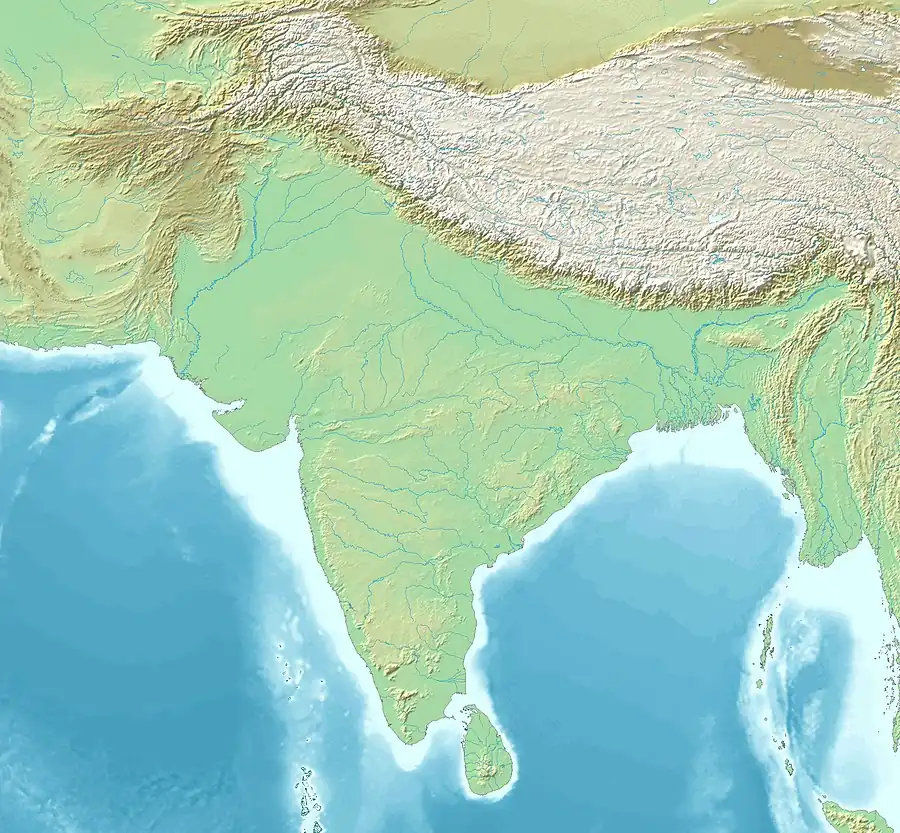

Location within Rajasthan  Battle of Haldighati (South Asia) | |||||||||

The Battle of Haldighati was a battle fought on 18 June 1576[lower-alpha 1] between the Mewar forces led by Maharana Pratap, and the Mughal forces led by Man Singh I of Amber. The Mughals carried the day after inflicting significant casualties on Mewar forces, although they failed to capture Pratap, who reluctantly retreated persuaded by his fellow commanders.

The siege of Chittorgarh in 1568 had led to the loss of the fertile eastern belt of Mewar to the Mughals. However, the rest of the wooded and hilly kingdom was still under the control of the Sisodias. Akbar was intent on securing a stable route to Gujarat through Mewar; when Pratap Singh was crowned king (Rana) in 1572, Akbar sent a number of envoys entreating the Rana to become a vassal like many other Rajput leaders in the region. However, Pratap refused to enter into a treaty, which led to the battle.

The site of the battle was a narrow mountain pass at Haldighati near Gogunda in Rajasthan. Sources differ on the strength of the respective armies but probably the Mughals outnumbered the Mewar forces by a factor of four to one. Despite initial successes by the Mewaris, the tide slowly turned against them and Pratap found himself wounded and the day lost. A few of his men under Jhala Man Singh covered his retreat in a rearguard action. The Mewar troops were not chased in their retreat by Man Singh for which he was banished from the Mughal court for some time by Akbar.

Despite the reverse at Haldighati, Pratap continued his resistance against the Mughals through guerrilla warfare, and by the time of his death had regained much of his ancestral kingdom.

Background

After his accession to the throne, Akbar had steadily settled his relationship with most of the Rajput states, with the exception of Mewar, acknowledged as the leading state in Rajasthan.[8] The Rana of Mewar, who was also the head of the distinguished Sisodia clan, had refused to submit to the Mughal. This had led to the siege of Chittorgarh in 1568, during the reign of Udai Singh II, ending with the loss of a sizeable area of fertile territory in the eastern half of Mewar to the Mughals. When Rana Pratap succeeded his father on the throne of Mewar, Akbar dispatched a series of diplomatic embassies to him, entreating the Rajput king to become his vassal. Besides his desire to resolve this longstanding issue, Akbar wanted the woody and hilly terrain of Mewar under his control to secure lines of communication with Gujarat.[9][10]

The first emissary was Jalal Khan Qurchi, a favoured servant of Akbar, who was unsuccessful in his mission. Next, Akbar sent Man Singh of Amber (later, Jaipur), a fellow Rajput of the Kachhwa clan, whose fortunes had soared under the Mughals. But he too failed to convince Pratap. Raja Bhagwant Das was Akbar's third choice who too failed to prompt Pratap in a treaty. According to Abu Fazl version, Pratap was swayed sufficiently to don a robe presented by Akbar and sent his young son, Amar Singh, to the Mughal court. However, this account of Abu-Fazal is a exaggeration as it is not corroborated even by the contemporary Persian chronicles, this account is not mentioned by Abd al-Qadir Badayuni and Nizamuddin Ahmad in their works. Further, In Tuzk-e-Jahangiri, Jahangir, stated that eldest son of Mewar king never visited the Mughal court prior to the treaty concluded in 1615 CE.[11]

A final emissary, Todar Mal, was sent to Mewar without any favourable outcome. With diplomacy having failed, war was inevitable.[9][10]

Prelude

Rana Pratap, who had been secure in the rock-fortress of Kumbhalgarh, set up his base in the town of Gogunda near Udaipur. Akbar deputed the Kachhwa, Man Singh, to battle with his clan's hereditary adversaries, the Sisodias of Mewar. Man Singh set up his base at Mandalgarh, where he mobilised his army and set out for Gogunda. Around 14 miles (23 km) north of Gogunda lay the village of Khamnor, separated from Gogunda by a spur of the Aravalli Range called "Haldighati" for its rocks which, when crushed, produced bright yellow sand resembling turmeric powder (haldi). The Rana, who had been apprised of Man Singh's movements, was positioned at the entrance of the Haldighati pass, awaiting Man Singh and his forces.[lower-alpha 2][13] The battle commenced three hours after sunrise on 18 June 1576.[14]

Army strength

Mewari tradition has it that the Rana's forces numbered 20,000, which were pitted against the 80,000-strong army of Man Singh. While Jadunath Sarkar agrees with the ratio of these numbers, he believes them to be just as exaggerated as the popular story of Rana Pratap's horse, Chetak, jumping upon Man Singh's war elephant.[15] Jadunath Sarkar gives the Mughal army as 10,000 strong.[16] Satish Chandra estimates that Man Singh's army consisted of 5,000–10,000 men, a figure which included both the Mughals and the Rajputs.[13]

According to Al Badayuni, who witnessed the battle, the Rana's army counted amongst its ranks 3,000 horsemen and around 400 Bhil archers led by Rana Punja, the Rajput chieftain of Panarwa. No infantry are mentioned. Man Singh's estimated forces numbered around 10,000 men.[16] Of these, 4,000 were members of his own clan, the Kachhwas of Jaipur, 1,000 were other Hindu reserves, and 5,000 were Muslims of the Mughal imperial army.[16]

Both sides possessed war elephants, but the Rajputs bore no firearms. The Mughals fielded no wheeled artillery or heavy ordnance, but did employ quite a number of muskets.[16]

Army formation

Rana Pratap's estimated 800-strong van was commanded by Hakim Khan Sur with his Afghans, Bhim Singh of Dodia, and Ramdas Rathor (son of Jaimal, who defended Chittor). The right-wing was approximately 500-strong and was led by Ramshah Tomar, the erstwhile king of Gwalior, and his three sons, accompanied by minister Bhama Shah and his brother Tarachand. The left-wing is estimated to have fielded 400 warriors, including Bida Jhala[lower-alpha 3] and his clansmen of Jhala. Pratap, astride his horse, led some 1,300 soldiers in the center. Bards, priests, and other civilians were also part of the formation and took part in the fighting. The Bhil bowmen brought up the rear.[17]

The Mughals placed a contingent of 85 skirmishers on the front line, led by Sayyid Hashim of Barha. They were followed by the vanguard, which comprised a complement of Kachhwa Rajputs led by Jagannath, and Central Asian Mughals led by Bakhshi Ali Asaf Khan. A sizeable advance reserve led by Madho Singh Kachhwa came next, followed by Man Singh himself with the centre. The Mughal left wing was commanded by Mulla Qazi Khan (later known as Ghazi Khan) of Badakhshan and Rao Lonkarn of Sambhar and included the Shaikhzadas of Fatehpur Sikri, kinsmen of Salim Chisti. The strongest component of the imperial forces were stationed in the pivotal right wing, which comprised the Sayyids of Barha. Lastly, the rear guard under Mihtar Khan stood well behind the main army.[18]

When army commingled with army

They stirred up the resurrection-day upon earth.

Two oceans of blood shocked together:

The soil became tulip-coloured from the burning waves.

Battle

The attack of the Rana led to the crumbling of the Mughal army's wings and centre. Abul Fazl says that the Mughal army was forced to retreat in the initial phase of the battle, however they soon rallied near a place called Rati-Talai (later called Rakt Talai).[21] Abul Fazl also says that this place was close to Khamnor while Badayuni says that the final battle took place at Gogunda.[21] The Mewar army followed the Mughals and attacked their left and right wings, the Mughal front broke but the reserves were able to hold the charge until Man Singh personally led the Imperial rear guard into the battle, he was followed by Mihtar Khan who started beating the kettle-drums and spread a rumour about the arrival of the Emperor's army reinforcements,[22][23] this raised the morale of the Mughal army and turned the battle in their favour, while also disheartening the exhausted soldiers of the Rana's Army.[24] The Mewari soldiers starting deserting in large numbers after learning about the arrival of reinforcements and the Mewar nobles upon finding the day lost, prevailed upon the Rana to leave the battlefield who had been already injured.[24] A Jhala chieftain called Man Singh took the Rana's place and donned some of his royal emblems by which the Mughals mistook him for the Rana. Man Singh Jhala was eventually killed, however his act of bravery gave the Rana enough time to safely retreat.[21]

Casualties

There are different accounts of the casualties in the battle.

- According to Jadunath Sarkar, the contemporary Mewari sources counted 46% of its total strength, or roughly 1,600 men, among the casualties.[lower-alpha 4]

- According to Abul Fazl and Nizamuddin Ahmed, 150 of the Mughals met their end, with another 350 wounded while the Mewar army lost 500 men.[26]

- Badayuni says that 500 men were killed in the battle, of which 120 were Muslims.[26]

- Later Rajasthani chroniclers have raised the casualties to 20,000 in order to emphasize the scale of the battle.[26]

There were Rajput soldiers on both sides. At one stage in the fierce struggle, Badayuni asked Asaf Khan how to distinguish between the friendly and enemy Rajputs. Asaf Khan replied, "Shoot at whomsoever you like, on whichever side they may be killed, it will be a gain to Islam."[27][28] K. S. Lal cited this example to estimate that Hindu soldiers died in large numbers for their Muslim lords in medieval India.[29]

Aftermath

Despite the victory in the battle, Man Singh did not allow the imperial army to chase the retreating Mewar troops and Pratap. According to historian Rima Hooja, this was done by Man Singh because of his personal respect for Pratap. However, Man Singh was reprimanded by Akbar for not capturing Pratap and was suspended from the Mughal court for sometime.[30][31][32] While Pratap was able to make a successful retreat, the Mughal troops captured his temporary capital Gogunda, albeit for a short time.[33] Subsequently, Akbar led a sustained campaign against the Rana, and soon most of the Mewar was under his control. Pressure was exerted by the Mughals upon the Rana's allies and other Rajput chiefs, and he was slowly but surely both geographically and politically isolated. The Mughals' focus shifted to other parts of the empire after 1585 CE, which allowed Pratap to recover much of his ancestral kingdom as attested by the contemporaneous epigraphic evidences, which included all 36 outposts of Mewar apart from Chittor and Mandalgarh which continued to remain under the Mughals.[25][34][35][36]

Reception

Contemporary

In a kāvya-narrative of the battle, Amrit Rai's biography of Man Singh asserts defeat of Rana Pratap.[37]

Modern

According to Satish Chandra, the Battle of Haldighati was, at best, "an assertion of the principle of local independence" in a region prone to internecine warfare.[38] Honour was certainly involved; but it was of Maharana Pratap, not Rajput or Hindu honour.[39]

Hindu Nationalists in post-colonial India have been accused of trying to appropriate Rana Pratap's legacy as part of their efforts to promote their vision of Indian culture, way of life, and propagate a negationist reading, where he went on to win the battle.[40] Most mainstream historians including D. N. Jha, Tanuja Kothiyal, and Rima Hooja reject these attempts as ahistorical.[40][41][42]

Notes

- ↑ Badauni, an eyewitness of the battle, stated it was fought on 21 June 1576 near Gogunda

- ↑ Sarkar and a few other sources prefer to call the spur Haldighat rather than Haldighati.[12]

- ↑ Sarkar also names him Bida Mana.

- ↑ According to Sarkar, "On the generally accepted calculation that the wounded are three times as many as the slain, the Mewar army that day endured casualties to the extent of 46 per cent of its total strength." Assuming that the total strength being spoken of here is 3,400, 46% would give a figure of 1,564 which has been rounded to 1,600.[25]

References

- ↑ de la Garza 2016, p. 56.

- ↑ Raghavan 2018, p. 67.

- ↑ Ram Vallabh Somani 1976, p. 230:"Several chiefs of Mewar lost their lives. Prominent among them were Netasingh, Dodiys Bhim, Sonagara Man, Rathor Ramdas, Sankardas, Tomar Ram Shah and his 3 sons, Hakim Khan Sur Rama Sandu etc"

- ↑ Ram Vallabh Somani 1976, p. 229: "Madhosingh Kachhawa inflicted a wound on the Rana, who counter attacked and killed Bahlol Khan, a senior Mughal officer"

- ↑ Ram Vallabh Somani 1976, p. 227:"The shelter of the Mughal centre, Kachhawa Jagnnath fought desperately and was about to fall but was rescued by the timely help of the Reserves sent under Kachhawa Madhosingh"

- ↑ Sharma, G.N. (1962). Mewar and the Mughal Emperors: 1526–1707 A. D. Shiva Lal Agarwala. p. 98. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

Qazi Khan, although he was but a Mulla, stood his gournd manfully, until receiving a similar blow on his right hand which wounded his thumb, being no longer able to hold his own, he receited (the saying) – Flight from overwhelming odds is one of the traditions of the Prophet and followed his men (in the retreat).

- ↑ Ram Vallabh Somani 1976, p. 228:"The Shekh Zadas of Sikari fled away: An arrow struck Shah Mansur, who soon left the field"

- ↑ Ram Vallabh Somani 1976, pp. 206–207.

- 1 2 Sarkar 1960, p. 75.

- 1 2 Chandra 2005, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Ram Vallabh Somani 1976, p. 223: "After settling the affairs of Rewaliya, a slave of Sher Khan and reducing Narayandas to extremities, Bhaga- wantdas paid a visit to Gogundah. Abu-lFazl records that the ‘Maharana sent his eldest son Amarsingh to the Mughal court and he himself begged excuse for his appearance" there. But his account is not worthy of credence. Badaoni, Nizamud-din Ahmad etc do not mention it, Jahangir in his Memoirs!” asserts that no eldest son of the ruler of Mewar had so for visited the Mughal court, before the settlement of 1615 A.D, Thus all these contemporary Mughal records lead us to believe that the account of Abw-l-Fazl is rather an exaggeration, The mission of Bhagawantdas totally failed"

- ↑ Sarkar 1960, pp. 75–77.

- 1 2 Chandra 2005, p. 120.

- ↑ Sarkar 1960, p. 80.

- ↑ Sarkar 1960, p. 77–78.

- 1 2 3 4 Sarkar 1960, p. 77.

- ↑ Sarkar 1960, pp. 78–79.

- ↑ Sarkar 1960, p. 78.

- ↑ Abu'l-Fazl. "PHI Persian Literature in Translation". persian.packhum.org. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ↑ Royal Asiatic Society.

- 1 2 3 Hooja, Rima (2006). A History of Rajasthan. Rupa & Company. pp. 469–470. ISBN 9788129115010.

- ↑ Sarkar, Jadunath (1984). History of Jaipur: C. 1503-1938. Orient Longman. p. 52. ISBN 9788125003335.

- ↑ Chandra, Satish (2006). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals Part - II. Har Anand. p. 120. ISBN 9788124110669.

- 1 2 Ram Vallabh Somani 1976, pp. 227–228.

- 1 2 Sarkar 1960, p. 83.

- 1 2 3 Hooja, Rima (2018). Maharana Pratap: The Invincible Warrior. Juggernaut. p. 117. ISBN 9789386228963. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ↑ Smith, Akbar the Great Mogul, pp.108–109.

- ↑ Lal, Studies in Medieval Indian History, pp.171–172.

- ↑ Lal, Kishori Saran (2012). Indian Muslims:Who Are They. New Delhi. ISBN 978-8185990101.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) ch. 5. Factors Contributing to the Growth of Muslim Population. - ↑ Ashoke Kumar Majumdar 1974, p. 327.

- ↑ Gopinath Sharma 1962, p. 109.

- ↑ Rima Hooja 2006:"Following the victory for the Mughal side, it is believed that Prince Man Singh of Amber gave orders that the Mughal army was not to pursue the Maharana’s soldiers. This is attributed to the fact that Man Singh personally respected Maharana Pratap. Having defeated him in battle at the command of his emperor, Man Singh probably did not wish to further harass the ruler and troops of Mewar. For this, Man Singh incurred the eventual, albeit short-lived, displeasure of Akbar. Soon afterwards, Imperial forces occupied much of Mewar"

- ↑ Ashoke Kumar Majumdar 1974, p. 329.

- ↑ Vanina, Eugenia (October 2019). "Monuments to Enemies? 'Rajput' Statues in Mughal Capitals". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 29 (4): 683–704. doi:10.1017/S1356186319000415. ISSN 1356-1863. S2CID 211645258.

- ↑ Ram Vallabh Somani 1976, p. 349: "During these years Akbar was engrossed in other affairs of his empire and found a new field for his ambition in the South, Pratap soon managed to recapture all the 86 important outposts of Mewar excluding Mandalgarh and hittor, Several copper plates, color phones of MSS and inscriptions coroborate this fact, A perusal of the copper plate!” of V.E, I644 (587 A.D.) of Rikhabdeva, the colo- phone of M.S, Gora Badal Qhopai! copied at Sadari (Godawar) in ‘V.E, I645 (688 A.D.), the copper plate of Pander’ (Jahazpur) dated V.E. 647 (590 A.D.) etc. all pertaining to his reign, prove that a considerable territory was regained by him, which he managed to enjoy throughout the latter part of his life"

- ↑ Dasharatha Sharma (1990). Rajasthan Through the Ages: From 1300 to 1761 A.D. Rajasthan State Archives. p. 145-147.

- ↑ Busch, Allison (1 January 2012). "Portrait of a Raja in a Badshah's World: Amrit Rai's Biography of Man Singh (1585)". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 55 (2–3): 315–317. doi:10.1163/15685209-12341237. ISSN 1568-5209.

- ↑ Chandra 2005, pp. 121.

- ↑ Eraly 2000, p. 144.

- 1 2 "Rajasthan to rewrite history books: Maharana Pratap defeated Akbar in Haldighati". Hindustan Times. 10 March 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ↑ Scroll Staff (9 February 2017). "Rajasthan ministers want to rewrite history books to show Maharana Pratap won Battle of Haldighati". Scroll.in. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ↑ "Breaking history: Maharana Pratap won Battle of Haldighati". The Indian Express. 9 February 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

Bibliography

- Ashoke Kumar Majumdar (1974). "Mewar". In R.C. Majumdar (ed.). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Mughal empire. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

- Chandra, Satish (2005). Medieval India (Part Two): From Sultanat to the Mughals. Har-Anand Publications. ISBN 9788124110669.

- Charley, Nancy. "The Elephants in the (Reading) Room – Royal Asiatic Society". royalasiaticsociety.org. Royal Asiatic Society. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- de la Garza, Andrew (2016). The Mughal Empire at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500-1605. Routledge. ISBN 9781317245315.

One year later the Rajputs attempted a similar all-out charge at Haldighati. The result was an even more decisive Mughal victory.

- Eraly, Abraham (2000). Emperors of the peacock throne : the saga of the great Mughals (Revised ed.). New Delhi: Penguin books. ISBN 9780141001432.

- Gopinath Sharma (1962). Mewar and the Mughal Emperors: 1526-1707 A. D. Shiva Lal Agarwala.

- Rima Hooja (2006). A history of Rajasthan. Rupa & Company. ISBN 978-8129108906.

- Raghavan, T.C.A. (2018). Attendant Lords: Bairam Khan and Abdur Rahim, Courtiers and Poets in Mughal India. HarperCollins.

Although most of the other Rajput rulers soon entered the Mughal alliance system, the kingdom of Mewar continued its resistance. Udai Singh was followed by his son, Pratap Singh, whose continued opposition to Mughal expansion – despite military defeats, most notably in the battle of Haldighati in 1576...

- Ram Vallabh Somani (1976). History of Mewar, from Earliest Times to 1751 A.D. Mateshwari. OCLC 2929852.

- Sarkar, Jadunath (1960). Military History of India. Orient Longmans. pp. 75–81. ISBN 9780861251551.