| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

_main_building.jpg.webp) | |

| Location | Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan |

| Part of | Fort and Shalamar Gardens in Lahore |

| Reference | 171-002 |

| Inscription | 1981 (5th Session) |

| Coordinates | 31°35′09″N 74°22′55″E / 31.58583°N 74.38194°E |

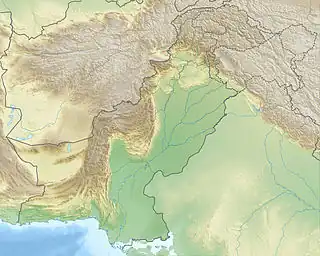

Location of Shalimar Gardens, Lahore in Lahore  Shalimar Gardens, Lahore (Punjab, Pakistan)  Shalimar Gardens, Lahore (Pakistan) | |

The Shalamar Gardens (Punjabi, Urdu: شالامار باغ, romanized: Shālāmār Bāgh) are a Mughal garden complex located in Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan. The gardens date from the period when the Mughal Empire was at its artistic and aesthetic zenith,[1] and are now one of Pakistan's most popular tourist destinations.

The Shalimar Gardens were laid out as a Persian paradise garden intended to create a representation of an earthly utopia in which humans co-exist in perfect harmony with all elements of nature.[2] Construction of the gardens began in 1641 during the reign of Emperor Shah Jahan,[2] and was completed in 1642.[3] In 1981 the Shalimar Gardens were inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site as they embody Mughal garden design at the apogee of its development.[1]

Names

The courtiers told the Maharaja Ranjit Singh "that Shala was a Turkic word which means pleasure and the mar means the place to live in".[4] "The arguments of the courtiers in favour of the Turkic signification of the word failing to make any impression on Ranjit Singh, he gave his own name to the garden, and called it “Shahla Bagh” شهلا باغ, “Shahla” meaning in Persian “sweetheart” with dark gray eyes and a shade of red and “Bagh” meaning “garden.”"[5]

The courtiers present passed high eulogies on the Maharájá's ingenuity in selecting so charming a name for the famous gardens of Láhore, and it was ordered, accordingly, that henceforward the gardens be called by that name, and written so in all public correspondence.[5]

The gardens are however still known as the "Shalimar Gardens" nowadays. According to Muhammad Ishtiaq Khan,

The most plausible interpretation, however, seems to be that the word "Shalamar" is a corruption of original "Shalimar" [...].[6]

Location

The Shalimar Garden is located next to the Grand Trunk Road, about 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) east of the Delhi Gate of the Walled City of Lahore. Near Bhaghbanpura Lahore

Background

_terrace_view_from_Farah_Baksh_(Bestower_of_Pleasure)_terrace.jpg.webp)

Lahore's Shalimar Gardens were built by the Mughal royal family primarily as a venue for them to entertain guests,[7] though a large portion was open to the general public. The gardens' design was influenced by the older Shalimar Gardens in Kashmir that were built by Shah Jahan's father, Emperor Jahangir.[7] Unlike the gardens in Kashmir which relied on naturally sloping landscapes, the waterworks in Lahore required extensive engineering to create artificial cascades and terraces.[8]

The Shalimar Gardens were designed as a Persian-style Charbagh "Paradise garden" - a microcosm of an earthly utopia.[2] Though the word Bagh is translated simply as "garden", bagh represents a harmonious existence between humans and nature, and represents a poetic connection between heaven and earth.[2] All natural elements of the bagh are appreciated - including the sun, moon, and air.[2] Muhammad Saleh Kamboh, historian to Shah Jahan, reported that the gardens of Kashmir inspired the design for the Shalimar Garden in Lahore,[2] and that a wide variety of trees and flowers grew together in the garden.[2]

The site was chosen for its stable water supply.[2] The project was managed by Khalilullah Khan, a noble of Shah Jahan's court, in cooperation with and Mulla Alaul Maulk Tuni. Ali Mardan Khan was responsible for most of the construction, and had a 100-mile-long canal built to bring water from the foothills of Kashmir to the site.[8]

The site of the Shalimar Gardens originally belonged to the Arain Mian Family Baghbanpura. Mian Muhammad Yusuf, then the head of the Arain Mian family, ceded the site of Ishaq Pura to the Emperor Shah Jahan in order for the gardens to be built. In return, Shah Jahan granted the Arain Mian family governance of the Shalimar Gardens, and the gardens remained under their custodianship for over 350 years.

History

Construction of the gardens began on 12 June 1641, and took 18 months to complete.[2] During the Sikh era, much of the garden's marble was pillaged and used to decorate the Golden Temple and the Ram Bagh Palace in nearby Amritsar,[9] while the gardens' costly agate gate was stripped and sold by Lehna Singh Majithia.[10]

In 1806 Maharaja Ranjit Singh ordered the Shalimar Gardens to be repaired.[11]

The Gardens were nationalised in 1962 by General Ayub Khan[12] because leading Arain Mian family members had opposed his imposition of martial law in Pakistan.

The annual Mela Chiraghan festival used to take place in the gardens until General Ayub Khan forbade it in 1958.

Design and layout

.jpg.webp)

Mughal Gardens were based upon Timurid gardens built in Central Asia and Iran between the 14th and 16th century.[2][13] A high brick wall richly decorated with intricate fretwork encloses the site in order to allow for the creation of a Charbagh paradise garden - a microcosm of an earthly utopia.[2]

The Shalimar Gardens are laid out in the form of a rectangle aligned along a north–south axis, and measure 658 metres by 258 metres, and cover an area of 16 hectares. Each terrace level is 4–5 metres (13–15 feet) higher than the previous level.

The uppermost terrace of the gardens is named Bagh-e-Farah Baksh, literally meaning Bestower of Pleasure. The second and third terraces are jointly known as the Bagh-e-Faiz Baksh, meaning Bestower of Goodness. The first and third terraces are both shaped as squares, while the second terrace is a narrow rectangle.

Shalimar's main entrance was onto the lower-most terrace, which was open to noblemen, and occasionally to the public.[2] The middle terrace was the Emperor's Garden, and contained the most elaborate waterworks of any Mughal garden.[2] The highest terrace was reserved for the Emperor's harem.[2]

The square shaped terraces were both divided into four equivalent smaller squares by long fountains flanked by brick khayaban walkways designed to be elevated in order to provide better views of the garden.[8] Cascades were made to flow over a marble paths in what are known as chadors, or "curtains" into the middle terrace. Water collected into a large pool, known as a haūz, over which a seating pavilion was made.[2]

Water features

The Shalimar Garden's contain the most waterworks of any Mughal Garden.[2] It contains 410 fountains, which discharge into wide marble pools, each known as a haūz. The enclosed garden is rendered cooler than surrounding areas by the garden's dense foliage, and water features[14] - a relief during Lahore's blistering summers, with temperature sometimes exceeding 120 °F (49 °C). The distribution of the fountains is as follows:

- The upper level terrace has 105 fountains.

- The middle level terrace has 152 fountains.

- The lower level terrace has 153 fountains.

- All combined, the Gardens has 410 fountains.

The Gardens have 5 water cascades including the great marble cascade and Sawan Bhadoon.

Garden pavilions

The buildings of the Gardens include:

|

|

Conservation

In 1981, Shalimar Gardens was included as a UNESCO World Heritage Site along with the Lahore Fort, under the UNESCO Convention concerning the protection of the world's cultural and natural heritage sites in 1972.

Gallery

Nigar Khana

Nigar Khana

.jpg.webp)

_by_Aunzee.jpg.webp)

East wall corner of the second level terrace

East wall corner of the second level terrace Minaret on the west wall corner of the second level terrace

Minaret on the west wall corner of the second level terrace A Mughal style structure inside the gardens

A Mughal style structure inside the gardens.JPG.webp)

_terrace_-_Shalimar_Gardens.jpg.webp)

See also

References

- 1 2 "Fort and Shalimar Gardens in Lahore". UNESCO. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 REHMAN, A. (2009). "Changing Concepts of Garden Design in Lahore from Mughal to Contemporary Times". Garden History. 37 (2): 205–217. JSTOR 27821596.

- ↑ Shalamar Gardens Gardens of the Mughal Empire. Retrieved 20 June 2012

- ↑ Nazir Ahmad Chaudhry (1998). Lahore: Glimpses of a Glorious Heritage. p. 279. ISBN 9789693509441..

- 1 2 Syad Muhammad Latif (1984). History of the Panjáb from the Remotest Antiquity to the Present Time. p. 361.

- ↑ Khan, Muhammad Ishtiaq (2000). World heritage: sites in Pakistan. p. 88.

- 1 2 Clark, Emma (2004). The Art of the Islamic Garden. Crowood. ISBN 186126609X. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- 1 2 3 Schimmel, Annemarie (2004). The Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture. Reaktion Books. p. 295. ISBN 1861891857. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

shalimar lahore public.

- ↑ Turner, Tom (2005). Garden History: Philosophy and Design 2000 BC – 2000 AD. Routledge. ISBN 9781134370825.

- ↑ Latif, Syad Muhammad (1892). Lahore: Its History, Architectural Remains and Antiquities. Oxford University: New Imperial Press.

- ↑ Hari Ram Gupta (1991). History of the Sikhs. ISBN 9788121505154..

- ↑ Upon A Trailing Edge: Risk, the Heart and the Air Pilot. Troubador Publishing Ltd. 2015. p. 268.

- ↑ "Shalimar Gardens". Gardens of the Mughal Empire. Smithsonian Productions. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ↑ Hann, Michael (2013). Symbol, Pattern and Symmetry: The Cultural Significance of Structure. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1472539007. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

External links

- UNESCO World Heritage Site Profile

- The Herbert Offen Research Collection of the Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum

- Sattar Sikander, The Shalimar: A Typical Muslim Garden, Islamic Environmental Design Research Centre

- Chapter on Mughal Gardens from Dunbarton Oaks discusses the Shalimar Gardens

- Irrigating the Shalimar Gardens in addition to canal named Shah Nahar Youtube link in Urdu