| ||||||

| Nicknames | Puerta de Hierro | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sport | Golf Polo Horse Riding Tennis Padel Croquet | |||||

| Founded | 1895[1][2][3][4][5] | |||||

| Based in | Avenida de Miraflores, s/n 28035 Madrid Spain | |||||

| Colors | ||||||

| Owner | Members | |||||

| President | The Count of Bornos | |||||

| Honorary President | Felipe VI | |||||

| Website | http://www.rcphierro.com | |||||

Real Club de la Puerta de Hierro (Spanish pronunciation: [reˈal ˈkluβ ðe la ˈpweɾta ðe ˈʝero]), commonly known as Puerta de Hierro, is a private country club based in Madrid, Spain. It owes its name to the nearby iron memorial arch.[6] Notorious for being associated with the royal families of Europe and the long-established elite, American President Gerald Ford called it "the club of kings and the king of clubs".[7]

It was established in 1895 as a polo club by a group of prominent noblemen led by the 16th Duke of Alba, with avid support from the then young king of Spain, Alfonso XIII. Along with the Ritz Hotel, it was founded as an effort to equal the likes of the most luxurious venues of London and Paris.[8] In 1904, Harry Colt and Tom Simpson designed in the club what was to become mainland Spain's first golf course, "el de arriba" (the upper).[9] In 1966, Robert Trent Jones Jr. and John Harris designed the second course, "el de abajo" (the lower), while Kyle Phillips was the architect of a third short nine-hole links.[10] The golf courses at Puerta de Hierro have hosted the Spain Open, Madrid Open, the 1970 Eisenhower Trophy and the 1981 Vagliano Trophy, and are considered "one of the finest and most classic courses in continental Europe".[11][12][13] Besides golf, the club has a long-recorded history and sections in the fields of equestrianism, polo, tennis, padel and croquet.

Puerta de Hierro is well known for its strict membership policy. For almost half a century, admission remains closed; only sons, daughters and spouses of existing members are allowed to join (the latter lose their status as members if they seek divorce). The club has been subsequently referred to as "the most exclusive and segregated club not only in Spain, but possibly in the world, where one can fraternize with the restrictive high society of Madrid".[14][15][16][17][18] Groucho Marx's phrase, "I don't care to belong to any club that will have me as a member" has been used to describe the club's highly sought-after membership.[19][20]

History

Early days

In 1876, a 19-year-old Alfonso XII ordered the construction of Madrid's first polo field at the Real Casa de Campo, at the time property of the crown. The main hypothesis behind this impulse points at the then Prince of Wales (later Edward VII), who during a visit to Madrid in late April 1876 mentioned the game to the king for the first time. The Prince of Wales had just returned from Colonial India, where he had witnessed one of the first official matches of polo, between a British garrison and the local Manipurs. Such was the enthusiasm of the future king Edward VII that his relative Alfonso was immediately captivated upon hearing his anecdotes.[21]

The sport of polo was relatively new to Western Europeans; in 1872, the Marquess of Torre Soto founded the "Jerez Polo Club" in Jerez de la Frontera while The Hurlingham Club published the official rules in 1873.[22][23][24] The Duke of Tamames, who had been educated in England, was also one of the main pioneers of polo in Spain.[21] Another important factor in the popularisation of the game was the great amount of business that British entrepreneurs were involved with in Spain, mainly transportation, sherry and mining i.e. Río Tinto, Osborne Group or González Byass. This common exposure to the British 'passe-temps' and colonies introduced in Spain not only polo but also golf and tennis.[25]

Young Alfonso XII, who had studied at Sandhurst, commissioned his admired equestrian teacher colonel Hamley to issue him with the newly published rules of Hurlingham. The king played polo up until his premature death in 1885, establishing the sport definitely amongst the upper classes of Spain. With the closure of the pitch at Casa de Campo as a result of the king's death, his close group of friends started playing polo in a large grassland in what is now Moratalaz in 1893. This group of enthusiasts comprised the dukes of Arión and Santoña and the marquesses of Larios, Villamejor and San Felices de Aragón.[25]

With the constantly growing devotion towards the game in Madrid, the idea of founding a club was more plausible than ever. This way, on 5 May 1895, the Duke of Alba established what was then called "Madrid Polo Club". Amongst the first board members were the Duke of Santoña, the Duke of Arión and the Count of Torre Arias, with the Queen Regent as honorary president. During the first board of the club, Spain played its first international polo game between the newly founded society and the Gibraltar Garrison Polo Club, in Granada, the 21st July 1897. The Spanish side included the brothers Leopoldo, José and Ernesto Larios and the Duke of Arión. The components of the English side are unknown, but it is most likely that they were officers of the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders, which were posted in Gibraltar during the time.[26]

Around the same time, Alfonso XIII, who had been born king, was not yet 10 years old. Despite his young age, his delicate health had prompted his mother the Queen Regent to ensure he practised many outdoor sports, and so the king had become a prolific horseman. A decade later, in 1908, he played polo in public for the first time, becoming the first monarch of the modern age to do so.[26] The young king had also become a keen golfer in England, and thus decided a 9-hole golf course be built in the Madrid Polo Club. In 1901, the course was inaugurated and became extremely popular, with figures such as Prince Carlos and his brother Prince Raniero being frequent players.

In 1907, the golf course had been so successful that the 391 members of the time acquired a larger estate known as "las Cuarenta Fanegas", making reference to the 40 fanegas of land that the Duke of Ahumada had granted for the construction of a garrison of the Guardia Civil in the mid 19th century.[27] It was located near present-day Santiago Bernabéu Stadium. With the considerable growth of golf within the club, it began to take the name of "Madrid Polo-Golf Club". For the design of the new course (the first 18-hole in the country), the board elected John Henry Taylor as architect. Not much is known today about this primitive course, other than its deep bunkers and the ring-like greens baptised then as bullrings, a uniqueness that the "American Golfer" magazine portrayed in one of its issues in April 1914.[28] The clubhouse resembled a British-Indian bungalow.

With the addition of lawn-tennis (on the lines of the Real Sociedad de Tenis de la Magdalena) in 1912, the club searched for larger terrains to cater for the new sport and the rapidly growing memberships. King Alfonso XIII offered some land in Monte del Pardo belonging to Heritage of the Crown for the symbolic price of 1,000 annual pesetas for a period of 20 years. The new terrain was situated near Puerta de Hierro, a triumphal arch built by Ferdinand VI in 1753. The transfer of all the facilities and members to the new location proved difficult. Back then, very few people had cars, the road to Puerta de Hierro was muddy and out of reach for those living in the city, which represented the great majority of members. Allegedly, the king had to speak to several influential members so that they would convince the rest to move out to the new terrains, claiming "it is an act of patriotism, since Madrid needs a country club that the best of those existing abroad would not surpass at all".[29] Once there was consensus, the members planned the funding of the construction of new facilities, which was wholly out of members' donations. The most significant contributions were made by the Queen Mother, who gave 8,160 pesetas (according to the archives of the Royal Palace of Madrid), and eight unnamed members who provided more than 500,000 pesetas altogether.[30] The Duke of Alba, who was the president at the time, managed to return half of what was lent by 1931, year in which he resigned.

The club subsequently took the name of the monument when the lease of grounds was signed on 8 July 1912, and added the prefix real (royal) along with the Royal Crown on bestowal of king Alfonso XIII, thus becoming "Real Club de la Puerta de Hierro".[29]

Rapid growth

After the contract was signed, works on the club began rather quickly. In almost two years, the construction of an eighteen-hole golf course, el de arriba (the upper), as well as a full size polo pitch and several tennis courts were finalised. The course was designed by Harry Colt taking advantage of the naturally occurring geographical accidents, featuring few bunkers and slightly shorter hole distances brought about by the firmness of the ground which maintained the ball rolling for longer. The architect stated that "it would be hard to find a space with more natural inclinations for marvelous greens to be built than this place".[31]

The club started to grow "with splendour" despite the severe effects of the Spanish–American War, followed by brief economic prosperity resulting from Spain's neutrality during World War I. In 1919, Alba wrote a letter to Colt expressing the unprecedented expansion that the club was going through. The three hundred members of 1913 had more than doubled. Reforms had to be made to increase the club house in size and the entry fee for new members raised. Puerta de Hierro introduced a "pay for use" policy whereby members had an extra fee for each sport they desired to play; 180 pesetas for those wishing to use the golf and tennis facilities and 350 for polo. Foreigners paid 50 pesetas monthly, but were exempt from any entry fee.[32]

The Roaring Twenties also left their imprint on the club. Although the socio-political situation was starting to shake with the Primo de Rivera dictatorship, Puerta de Hierro continued celebrating all sorts of flamboyant dinners and parties. From 1917, dancing events until dawn were relatively common to the extent that many of them were organized at the Ritz Hotel. Social sporting events and gymkhanas also continued to take place, with the regular attendance of members of the royal families of Europe. The club had positioned itself as one of the common stops for foreign diplomacy and reigning monarchs as they visited Madrid. Ambassadors were automatically given temporary memberships, many of them using the club to take their respective heads of state for lunch or sport. Even today, most ambassadors are still granted memberships during their time in office.[32]

During the 1920s and 1930s, several prominent figures were frequent guests at Puerta de Hierro, most notably the kings of Sweden and Greece and the princes of Piedmont, Ligne and Wales (this last one being a usual member). Douglas Fairbanks visited the club on two occasions: in October 1933, when he had lunch with the then president, Portago, and a second in March 1936 with his new wife, Sylvia Ashley.[33]

King Gustaf V of Sweden, who played tennis in Cannes with several club members, used to visit Puerta de Hierro during his stays in Madrid. On 27 April 1927, the ambassador of Spain to Sweden, the Count of San Esteban de Cañongo, organized a lunch in his honour in the main hall. In the afternoon, the king played a doubles tennis match.[34]

War years

The weak political system of the Second Spanish Republic and the rise of nationalism led to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in July 1936. Shortly into the conflict, Puerta de Hierro was seized by the Juventudes Socialistas Unificadas, who used the grounds to accommodate themselves. Later that year the club was occupied by the Rosal Column, who established their headquarters in the club house and dug out several trenches and machine gun nests throughout the estate, including the golf courses. The club, which was situated in the very centre of the Madrid front, was, for the most part, Republican territory, while the Casa de Campo marked the beginning of the Nationalist area. It was only during this time that the club had no president (1936-1939).

After the war, the club's terrains were devastated;[35] the rug-like golf course disappeared, the club house had been demolished and the polo pitch was a "graveyard of tanks".[36] Reports of April 1939 compare the golf course to the surface of the Moon, "although a few fanatics have managed to play four holes, it's all a matter of enthusiasm".[37] This was not an excuse however, for many of the members, who tirelessly rebuilt the club after the war.

At the end of 1939, a group of members and workers headed by previous club president Rafael Silvela (a grandchild of Manuel Silvela, whose brother was Prime Minister of Spain) proposed the reconstruction of the facilities. The group aimed to find as many previous members as possible, but the task soon proved difficult given that the archives had been burnt down with the club house. Luckily for Silvela, Ángel Duran, a worker who had been gatekeeper at the club for many years would be of outstanding help. One of Mr. Durán's tasks during his time working at Puerta de hierro had been the collection and charge of club fees, which meant that he recalled the addresses of the majority of members prior to the war. This way, Mr. Durán and the chief of registrars spent months travelling through Madrid in search of those who had survived the war, waiting for long hours outside hotels and embassies, where many who had lost their homes stayed.

On 9 October 1939, the group managed to gather sufficient ex-members for the enterprise to take off, in what was the first Board of the Reconstruction Committee, with an initial capital budget of 25,000 pesetas. Among those who contributed greatly were the United Kingdom Embassy and the United States Embassy, who provided all the golfing equipment and seeds for the greens.[38] Puerta de Hierro's first board after the war was celebrated on 21 October 1939 at The Palace Hotel, with one of the policies discussed being the "employee aid", which consisted of a significant raise in worker's salaries, who post-war had found themselves in great poverty. The closing policy was to reintegrate the prefix "real" to the name of the club and to retrieve its symbolism, including coat of arms and red/yellow colours.

In 1940, scarcely a year after the end of the Spanish Civil War, Puerta de Hierro showed great signs of recovery. The number of members was close to one thousand, similar to the spring of 1936. Nine holes had been opened and the remaining nine were on their way, the six tennis courts and their pavilion were functioning and twenty-four equestrian boxes had been built.[38]

On June 23, 1940, Edward VIII visited Madrid as Duke of Windsor, staying at the Ritz Hotel. The purpose of this extra-official visit, in the midst of the German invasion of France, was to negotiate possible alliances with Nazi Germany from Axis-leaning Spain.[39] On June 24, The Duke of Windsor spent the day at Puerta de Hierro, where he played golf and attended a Saint John's Eve party at the club accompanied by the then Marquess of Estella, son of former dictator Miguel Primo de Rivera and brother of José Antonio Primo de Rivera. During the celebration, Windsor was surprised with news from a British aristocrat who owned wineries in Spain and had recently returned from London. As he was told, his brother King George VI had granted an Earldom to former Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, who he loathed. He complained "why on earth would Bertie reward such nauseating reptile?".[40]

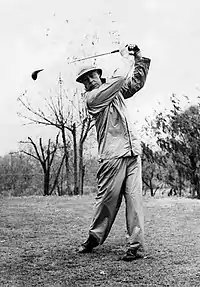

The Duke of Windsor returned to the club on several occasions, most famously in 1960, when he played golf under pouring rain.[41]

Franco era

The most important works of recovery, those of the club house, remained an unsettled priority. Although the club had already contacted the Dirección General de Regiones Devastadas (Directorate-General of Devastated Regions), a government body created by Franco for the reconstruction of Spain after the war, it would not be until 1942 that the plan for the rebuilding of Puerta de Hierro's club house would be accepted.[42] The project was assigned to Luis Gutiérrez Soto, a renowned Art Deco-rationalist architect at the time.[43] The club house was built in a neo-herrerian-Spanish baroque style, very much like the surrounding buildings around El Pardo. It was inaugurated in 1944.

In 1948, one of the main symbols of Puerta de Hierro was built on popular demand from members. The sculpture of a wild boar being chased by a dog (el jabalí y el perro) was erected in front of the club house's main entrance. This hunting scene is thought to have been inspired by Goya's painting, The Boar Hunt. The figure, surrounded by a small pond, was designed by the Count of Yebes, who combined his job as an architect with his passion for hunting.[44]

The late 1940s and early 1950s saw the birth of several parts of the club. The construction of a pool, which had been desired by many young members for some time, but rejected by the eldest members for its "lowly social implications", began. This decade also saw the birth of the infant facilities, which were set more than a mile away from the club house.[44] These continue to cater for members up until the age of fourteen. Another important project was the reforestation of the club's grounds, which had lost their emblematic stone pines during the war.

Polo

Around 1920, the level of polo played at Puerta de Hierro was already considerable, to the extent that the club decided to put together a team with the aim of taking part in the Antwerp Summer Olympics. The team was made up of the following members: the Duke of Alba and his brother the Duke of Peñaranda, the Marquess of Villabrágima, the Count of la Maza and José de Figueroa as substitute. The group, which represented Spain in men's polo at the Olympics, lost the final to its historic rival, Great Britain on 31 July in Ostend, by 13–11. They won the silver medal.[45]

In the 1924 Paris Olympics, another team made up entirely of Puerta de Hierro members represented Spain in men's polo. This time, the Duke of Alba and José de Figueroa were replaced by the Count of Velayos and Justo San Miguel, respectively. The team earned a respected fourth place.

During the 1920s, the most distinguished players were the King, Peñaranda,[46] Maza and particularly Villabrágima, who was Mayor of Madrid in 1921 and one of the most successful polo players of Spain, having been the only one to reach handicap 8.[47] In 1929, he won a Grand Prix cup at the Roehampton Tournament with Alfonso XIII.[48] In general, all of the male sons of Álvaro de Figueroa (San Damián, Yebes, Velayos and José) stood out in polo. Other players who showed potential were Juan Antonio Echevarrieta, José Luis Aznar and Antonio Portago, father of Alfonso and club president between 1931 and 1932.

From his return from the 1920 Olympics, the king made a strong effort to encourage those in the military to play polo. The financial constraints of the sport had meant it was exclusively practised by the wealthiest groups in society. Unlike in Great Britain, where polo had been introduced by the military, in Spain, it was first played by aristocrats who brought the game with them from their boarding school days. The Administration lowered the costs of playing polo to allow for new clusters to enjoy the game. This way, military polo was well established in 1924.[49] The first military polo cup was played in 1924 at Casa de Campo, between the Royal Guard and the Equestrian School. The trophy, which was donated by the Duchess of Andría, was won 1-0 by the Equestrian School. In 1925, general Primo de Rivera commissioned the Mexican polo player, Manuel de Escandón, with the creation of an international military polo competition.

By the 1930s, the sport seemed to continue growing, but it was still not affordable to all. A great deal of this growth was attributable to captain Penche, who laid the basis of military polo in Spain. He had been sent in 1926 to London by the War Minister, Juan O'Donnell, to study the practice of polo within the British Army.[49] However, this growth would soon decline as a result of the Great Depression. The Spanish Civil War would tear through the sport definitely.

Nonetheless, earlier in 1928, Spain had sent three army officers to participate at team jumping in the Amsterdam Olympics: the captains Bohorques, Navarro and García. Out of the three, the first two were Puerta de Hierro members. Bohorques rode "Zalamero", Navarro rode "Zapatazo" and García did so with "Revistada". The 12th August the three won gold in team jumping, and were personally presented with the medal by Queen Wilhelmina.[50] This was the first ever gold medal obtained by Spain at the olympics.[51][52][53]

Club Presidents

- 1895 – 1896 The Duke of Alba[54]

- 1896 – 1901 The Duke of Arión[54]

- 1901 – 1905 The Duke of Santoña[54]

- 1905 – 1931 The Duke of Alba[54]

- 1931 – 1932 The Marquess of Portago[54]

- 1932 – 1936 Rafael Silvela y Tordesillas[54]

- 1939 – 1944 Joaquín Santos-Suárez y Jabat[54]

- 1944 – 1950 Rafael Silvela y Tordesillas[54]

- 1950 – 1952 The Count of Fontanar[54]

- 1952 – 1954 The Duke of Lécera[54]

- 1954 – 1958 The Count of Fontanar[54]

- 1958 – 1962 The Duke of Frías[54]

- 1962 – 1966 H.R.H. Prince Ataúlfo de Órleans y Sajonia-Coburgo-Gotha[54]

- 1966 – 1970 The Marquess of Silvela[54]

- 1970 – 1974 The Count of Villacieros[54]

- 1974 – 1978 The Duke of Fernán Núñez[54]

- 1978 – 1986 The Duke of Bailén[54]

- 1986 – 1990 The Marquess of Estepa[54]

- 1990 – 1994 The Marquess of Bolarque[54]

- 1994 – 2006 The Count of Elda[54]

- 2006 – 2011 Pedro Morenés y Álvarez de Eulate[54]

- 2011 – 2016 Luis Álvarez de las Asturias Bohorques y Silva[54]

- 2016 – The Count of Bornos[54]

Honours

National honours

See also

- Real Sociedad de Tenis de la Magdalena

- Real Club de Polo de Barcelona

- List of golf clubs granted Royal status

References

- ↑ "ABC MADRID 04-07-2014 página 96 - Archivo ABC". abc. September 6, 2019.

- ↑ Riordan & Krüger 2003, p. 125.

- ↑ "El marido de Esperanza Aguirre: Ahora, el presidente es él". ELMUNDO. March 19, 2016.

- ↑ Laffaye 2012, p. 234.

- ↑ "Los secretos del Club Puerta de Hierro: el lugar donde se casan los Entrecanales o los Borbón". Vanitatis (El Confidencial). September 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Mazo, Violeta: Sólo apto para socios - 25 June 2004". 25 June 2004. CincoDías EL PAÍS

- ↑ Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 117.

- ↑ "Castelló, Elena: Así es por dentro el club más exclusivo de España, y donde la nieta de Suárez celebra hoy su boda - 21 April 2018". 21 April 2018. Vanity Fair

- ↑ Ten Golf: El club de golf más antiguo de España cumple 125 años (Puerta de Hierro is the second oldest in Spain, after Real Club de Golf of Las Palmas, founded 1891, but is the oldest in mainland Spain)

- ↑ "Real Club Puerta de Hierro under way with Colt restoration work". Golf Course Architect.

- ↑ "Real Club de la Puerta de Hierro (Arriba) - Top 100 Golf Courses of Spain". www.top100golfcourses.com.

- ↑ "Real Club de la Puerta de Hierro (Abajo) - Top 100 Golf Courses of Europe". www.top100golfcourses.com.

- ↑ "Real Club de la Puerta de Hierro - LUXOViS | The World of the Luxury! Find the luxury Hotels, Villas, Restaurants, Shops, Events, News, Golf, Beauty and Health - Find and book the Luxury in the world, make a luxury reservations". luxovis.com.

- ↑ "Los clubes privados de lujo más exclusivos para pasar el verano". El Economista. July 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Extraterrestres en Puerta de Hierro". El País. July 17, 1982.

- ↑ "Real Club Puerta de Hierro: el feudo de la derecha". El Confidencial. April 1, 2015.

- ↑ García Mateache 2020, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Romero 2018, p. 90.

- ↑ "Aristocracia". El País. January 16, 2022.

- ↑ Hello! No. 1030 - 22 July 2008 p. 11

- 1 2 Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 18.

- ↑ Miller & Hayes 1902, p. 333.

- ↑ Dale 1905, p. 24.

- ↑ Drybrough 1906, p. 268.

- 1 2 Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 19.

- 1 2 Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 20.

- ↑ Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 23.

- ↑ Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 25.

- 1 2 Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 37.

- ↑ Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 38.

- ↑ Gómez Laínez 2010, pp. 38–40.

- 1 2 Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 45.

- ↑ Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 46.

- ↑ Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 85.

- ↑ Hernández Barral 2021, p. 39.

- ↑ Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 48.

- ↑ Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 89.

- 1 2 Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 91.

- ↑ Juárez, Javier: El 'contubernio' del Hotel Ritz - 31 January 2017 - El Mundo

- ↑ Vilches 2013, pp. 22–24.

- ↑ Limited, Alamy. "Stock Photo - 1968 - The Duke of Windsor King Edward VIII - The Duke of Windsor plays golf in the rain Pouring rain did not deter the Duke of Windsor from playing a round of golf at the Real". Alamy.

- ↑ Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 92.

- ↑ Arquitectos de Madrid 1949, pp. 61–68.

- 1 2 Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 95.

- ↑ Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 52.

- ↑ Hernández Barral 2012, p. 84.

- ↑ Laffaye 2012, p. 111.

- ↑ Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 53.

- 1 2 Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 57.

- ↑ Gómez Laínez 2010, p. 58.

- ↑ Olympic profile: José Álvarez de las Asturias Bohórques y Goyeneche

- ↑ Olympic profile: José Navarro y Morenés

- ↑ Olympic profile: Julio García Fernández de los Ríos

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Gómez Laínez 2010, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Real Orden del Mérito Deportivo 2013 csd.gob.es

Bibliography

- Arquitectos de Madrid, Colegio Oficial de (February 1949). "El Club de Puerta de Hierro en Madrid" (PDF). Revista Nacional de Arquitectura. 86 (4): 61–68.

- Cazaza en África, Marquess of (2022). La Mala Sangre. Ediciones B. ISBN 978-84-66671-87-3 – via Google Books.

- Dale, Thomas F. (1905). Polo: Past and Present. Country Life Library of Sport.

- Drybrough, Tom b. (1906). Polo. Longman.

- Espinosa de los Monteros, Patricia (2020). Clubs Históricos de España. Ediciones El Viso. ISBN 978-84-12084-62-7.

- García Mateache, Aurora (2020). La Finca: Una Familia con Poder. El Amor a una Tierra. Una Periodista en Busca de la Verdad. La Esfera de los Libros. ISBN 978-84-91648-35-2 – via Google Books.

- Gómez Laínez, Mariola (2010). El Real Club de la Puerta de Hierro. Ediciones El Viso. ISBN 978-84-95241-75-7.

- Hernández Barral, José Miguel (2012). Grandes de España: Distinción y Cambio Social, 1914-1931 (PDF) (PhD). Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

- Hernández Barral, José Miguel (2021). "Chapter 3: Polo: Social Distinction and Sports in Spain, 1900-1950". In Dichter, Heather; Lake, Robert J.; Dyreson, Mark (eds.). New Dimensions of Sport in Modern Europe: Perspectives from the 'Long Twentieth Century'. Routledge. pp. 27–46. ISBN 978-03-67712-96-9.

- Laffaye, Horace A. (2012). Polo in Britain: A History. McFarland. ISBN 978-07-86465-11-8.

- Miller, Edward D.; Hayes, Matthew M. (1902). Modern Polo. Hurst and Blackett.

- Romero, Ana (2018). El Rey Ante el Espejo : Crónica de una Batalla: Legado, Asedio y Política en el Trono de la Reina Letizia y Felipe VI. La Esfera de los Libros. ISBN 978-84-91641-80-3 – via Google Books.

- Riordan, James; Krüger, Arnd (May 22, 2003). European Cultures in Sport: Examining the Nations and Regions. Intellect Books. ISBN 978-18-41500-14-0 – via Google Books.

- Vilches, Juan (2013). Te Prometo un Imperio. Plaza & Janés. ISBN 978-84-01353-78-9.