The research-based design process is a research process proposed by Teemu Leinonen,[1][2] inspired by several design theories.[3][4][5] It is strongly oriented towards the building of prototypes and it emphasizes creative solutions, exploration of various ideas and design concepts, continuous testing and redesign of the design solutions.

The method is firmly influenced by the Scandinavian participatory design approach. Therefore, most of the activities take place in a close dialogue with the community that is expected to use the tools or services designed.

Phases

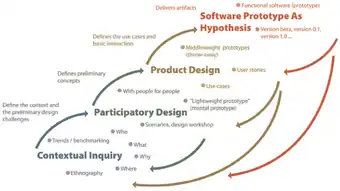

The process can be divided into four major phases, although they all happen concurrently and side by side. At different times of the research, researchers are asked to put more effort into different phases. The continuous iteration, however, asks researchers to keep all the phases alive all the time: contextual inquiry, participatory design, product design, prototype as hypothesis.

Contextual inquiry

Contextual inquiry refers to the exploration of the socio-cultural context of the design. The aim is to understand the environment, situation, and culture where the design takes place. The results of the contextual inquiry are better understanding of the context by recognizing in it possible challenges and design opportunities. In this phase, design researchers use rapid ethnographic methods, such as participatory observation, note-taking, sketching, informal conversations, and interviews. At the same time as the field work, the design researchers are doing a focused review of the literature, benchmarking existing solutions, and analyzing trends in the area in order to understand and recognise design challenges.

Participatory design

Throughout the contextual inquiry design researchers start to develop some preliminary design ideas, which would be developed during the next stage—participatory design—in workshops with different stakeholders. The participatory design sessions tend to take place with small groups of 4 to 6 participants. A common practice is to present the results as scenarios made by the design researchers containing challenges and design opportunities. In the workshop, the participants are invited to come up with design solutions to the challenges and to bring to the discussion new challenges and solutions.

Since one of the main features of the research-based design is its participatory nature, the user's involvement is an integral part of the process. In this regard, participatory design workshops are organized during the different stages in order to validate initial ideas and discuss the prototypes at different stage of development.

Product design

The results of the participatory design are analysed in a design studio by the design researchers who use the materials from the contextual inquiry and participatory design sessions to redefine the design problems and redesign the prototypes. By keeping a distance from the stakeholders, in the product design phase the design researchers will get a chance to analyse the results of the participatory design, categorize them, use specific design language related to implementation of the prototypes, and finally make design decisions.

Prototype as hypothesis

Ultimately, the prototypes are developed to be functional on a level that they can be tested with real people in their everyday situations. The prototypes are still considered to be a hypothesis, prototypes as hypothesis, because they are expected to be part of the solutions for the challenges defined and redefined during the research. It remains to the stakeholders to decide whether they support the assertions made by the design researchers. Therefore the first prototypes brought to the use of the real people can be considered to be also minimum viable products.

Research-based design is not to be confused with design-based research or educational design research.[6][7][8][1][9][10] In research-based design, which builds on art and design tradition, the focus is on the artifacts, the end-results of the design. The way the artifacts are, the affordances and features they have or do not have, form an important part of the research argumentation. As such, research-based design as a methodological approach includes research, design, and design interventions that are all intertwined.

References

- 1 2 3 Leinonen, T., Toikkanen, T. & Silfvast, K. (2008). Software as Hypothesis: Research-Based Design Methodology. In the Proceedings of Participatory Design Conference 2008. Presented at the Participatory Design Conference, PDC 2008, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA: ACM.

- ↑ Leinonen, Teemu (2010). Designing Learning Tools. Methodological Insights. Aalto University. ISBN 978-952-60-0032-9.

- ↑ Ehn, P. & Kyng, M. (1987). "The Collective Resource Approach to Systems Design". In G. Bjerknes, P. Ehn & M. Kyng (Eds.), Computers and Democracy: A Scandinavian Challenge (pp. 17–57).Avebury.

- ↑ Schön, D.A. (1987). Educating the Reflective Practitioner. Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- ↑ Nelson, H. & Stolterman, E. (2003). The Design Way: Intentional Change in an Unpredictable World: Foundations and Fundamentals of Design Competence. New Jersey: Educational Technology Publications

- ↑ Barab, S.A. & Squire, K. (2004). Design-Based Research: Putting a Stake in the Ground. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 1-14.

- ↑ The Design-Based Research Collective. (2003). Design-based research: An emerging paradigm for educational inquiry. Educational Researcher, 5-8.

- ↑ Fallman, D. (2007). Why Research-Oriented Design Isn’t Design-Oriented Research: On the Tensions Between Design and Research in an Implicit Design Discipline. Knowledge, Technology & Policy, 20(3), 193-200.

- ↑ "Conducting Educational Design Research". Routledge & CRC Press. Retrieved 2023-03-16.

- ↑ McKenney, Susan; Reeves, Thomas C. (2014), Spector, J. Michael; Merrill, M. David; Elen, Jan; Bishop, M. J. (eds.), "Educational Design Research", Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology, New York, NY: Springer, pp. 131–140, doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-3185-5_11, ISBN 978-1-4614-3185-5, S2CID 260548322, retrieved 2023-03-16