Regenerative design is an approach to designing systems or solutions that aims to work with or mimic natural ecosystem processes for returning energy from less usable to more usable forms.[1] Regenerative design uses whole systems thinking to create resilient and equitable systems that integrate the needs of society with the integrity of nature. Regenerative design is an active topic of discussion in engineering, landscape design, food systems, and community development.[2][3] [4][5]

The regenerative design paradigm encourages designers to use systems thinking, applied permaculture design principles, and community development processes to design human and ecological systems. The development of regenerative design has been influenced by approaches found in biomimicry, biophilic design, ecological economics, circular economics, as well as social movements such as permaculture, transition and the new economy. Regenerative design can also refer to the process of designing systems such as restorative justice, rewilding and regenerative agriculture.

Regenerative design is increasingly being applied in such sectors as agriculture, architecture, community planning, cities, enterprises, economics and ecosystem regeneration.[6] These designers are using the principles observed in systems ecology in their design process and recognize that ecosystems are resilient largely because they operate in closed loop systems. Using this model regenerative design seeks feedback at every stage of the design process. Feedback loops are an integral to regenerative systems as understood by processes used in restorative practice and community development.

Regenerative design is interconnected with the approaches of systems thinking and with New Economy movement. The 'new economy' considers that the current economic system needs to be restructured.[7] The theory is based on the assumption that people and the planet should come first, and that it is human well-being, not economic growth, which should be prioritized.

Whereas the highest aim of sustainable development is to satisfy fundamental human needs today without compromising the possibility of future generations to satisfy theirs, the goal of regenerative design is to develop restorative systems that are dynamic and emergent, and are beneficial for humans and other species. This regeneration process is participatory, iterative and individual to the community and environment it is applied to. This process intends to revitalize communities, human and natural resources, and society as a whole.

In recent years regenerative design is made possible on a larger scale using open source socio- technical platforms and technological systems as used in SMART cities. It includes community and city development processes like gathering feedback, participatory governance, sortition and participatory budgeting.

History

Permaculture

The term permaculture was developed and coined by David Holmgren, then a graduate student at the Tasmanian College of Advanced Education's Department of Environmental Design, and Bill Mollison, senior lecturer in environmental psychology at University of Tasmania, in 1978.[8] The word permaculture originally referred to "permanent agriculture",[9][10] but was expanded to stand also for "permanent culture", as it was understood that social aspects were integral to a truly sustainable system as inspired by Masanobu Fukuoka's natural farming philosophy. Regenerative design is integral to permaculture design.

In 1974, David Holmgren and Bill Mollison first started working together to develop the theory and practice of permaculture. They met when Mollison spoke at a seminar at the Department of Environmental Design and began to work together. During their first three years together Mollison worked at applying their ideas, and Holmgren wrote the manuscript for what would become Permaculture One: a perennial agricultural system for human settlements as he completed his environmental design studies, and submitted it as the major reference for his thesis. He then handed the manuscript to Mollison for editing and additions, before it was published in 1978.[11]

Regenerative organic agriculture

Robert Rodale, son of American organic pioneer and Rodale Institute founder J.I. Rodale, coined the term 'regenerative organic agriculture.'[12] The term distinguished a kind of farming that goes beyond simply 'sustainable.' Regenerative organic agriculture "takes advantage of the natural tendencies of ecosystems to regenerate when disturbed. In that primary sense it is distinguished from other types of agriculture that either oppose or ignore the value of those natural tendencies."[12] This type of farming is marked by "tendencies towards closed nutrient loops, greater diversity in the biological community, fewer annuals and more perennials, and greater reliance on internal rather than external resources."[12]

John T. Lyle (1934–1998), a landscape architecture professor saw the connection between concepts developed by Bob Rodale for regenerative agriculture and the opportunity to develop regenerative systems for all other aspects of the world. While regenerative agriculture focused solely on agriculture, Lyle expanded its concepts and use to all systems. Lyle understood that when developing for other types of systems, more complicated ideas such as entropy and emergy must be taken into consideration.

In the built environment

In 1976, Lyle challenged his landscape architecture graduate students at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona to "envision a community in which daily activities were based on the value of living within the limits of available renewable resources without environmental degradation."[13] Over the next few decades an eclectic group of students, professors and experts from around the world and crossing many disciplines developed designs for an institute to be built at Cal Poly Pomona. In 1994, the Lyle Center for Regenerative Studies opened after two years of construction.[13] In that same year Lyle's book Regenerative Design for Sustainable Development was published by Wiley.[14] In 1995 Lyle worked with William McDonough at Oberlin College on the design of the Adam Joseph Lewis Center for Environmental Studies completed in 2000.[15] In 2002 McDonough's book, the more popular and successful, Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things was published reiterating the concepts developed by Lyle.[16] Swiss architect Walter R. Stahel developed approaches entirely similar to Lyle's also in the late 1970s but instead coined the term cradle-to-cradle design made popular by McDonough and Michael Braungart.[17]

Sim Van Der Ryn is an architect, author, and educator with more than 40 years of experience integrating ecological principles into the built environment.[18] Author of eight publications, one of his most influential books titled Ecological Design, published in 1996, provides a framework for integrating human design with living systems. The book challenges designers to push beyond "green building" to create buildings, infrastructure and landscapes that truly restore and regenerative of the surrounding ecosystems.[19]

The Living Building Challenge (LBC) is recognized as the most stringent and progressive green building standard that can be applied to any building type around the world. The goal is to create Living Buildings that incorporate regenerative design solutions that actually improve the local environment rather than simply reducing harm. LBC was created by Jason F. McLennan and administered by the non-profit International Living Future Institute (ILFI), a global network dedicated to creating a healthy future for all. In addition to the Living Building Challenge, ILFI runs the Living Community Challenge, Living Product Challenge, Net Zero Energy Certification, the Cascadia Green Building Council, Ecotone Publishing, Declare, JUST and other leading-edge programs.

“What if every single act of design and construction made the world a better place?” — The Living Building Challenge (LBC).

Regenerative Cultures

Regenerative design advocate and author Daniel Christian Wahl argues that regenerative design is about sustaining "the underlying pattern of health, resilience and adaptability that maintain this planet in a condition where life as a whole can flourish."[20] In his book, Designing Regenerative Cultures, he argues that regeneration is not simply a technical, economic, ecological or social shift, but has to go hand-in-hand with an underlying shift in the way we think about ourselves, our relationships with each other and with life as a whole.

Green vs. sustainable vs. regenerative

There is an important distinction that should be made between the words 'green', 'sustainable', and 'regenerative' and how they influence design.

Green design

In the article Transitioning from green to regenerative design, Raymond J. Cole explores the concept of regenerative design and what it means in relation to 'green' and 'sustainable' design. Cole identifies eight key attributes of green buildings:

- Reduces damage to natural or sensitive sites

- Reduces the need for new infrastructure

- Reduces the impacts on natural feature and site ecology during construction

- Reduces the potential environmental damage from emissions and outflows

- Reduces the contributions to global environmental damage

- Reduces resource use – energy, water, materials

- Minimizes the discomfort of building occupants

- Minimizes harmful substances and irritants within building interiors

By these eight key attributes, 'green' design is accomplished by reducing the harmful, damaging and negative impacts to both the environment and humans that result from the construction of the built environment. Another characteristic that separates 'green' design is that it is aimed at broad market transformation and therefore green building assessment frameworks and tools are typically generic in nature.[21]

Sustainable design

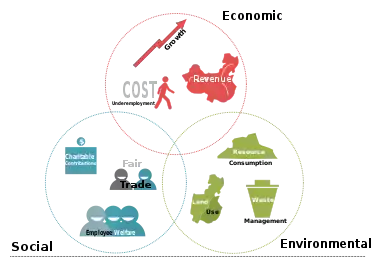

'Sustainable' and 'green' are for the most part used interchangeably; however, there is a slight distinction between them. 'Green' design is centralized around specifically decreasing environmental impacts from human development, whereas sustainability can be viewed through an environmental, economic or social lens. The implication is that sustainability can be incorporated into all three aspects of the Triple Bottom Line: people, planet, profit.

The definition of sustainable or sustainability has been widely accepted as the ability to meet the needs of the current generation without depleting the resources needed to meet the needs of future generations. It "promotes a bio-centric view that places the human presence within a larger natural context, and focuses on constraints and on fundamental values and behavioral change."[21] David Orr defines two approaches to sustainability in his book Ecological Literacy: "technological sustainability" and "ecological sustainability."[22] "Technological sustainability" emphasizes the anthropocentric view by focusing on making technological and engineering processes more efficient whereas "ecological sustainability" emphasizes the bio-centric view and focuses on enabling and maintaining the essential and natural functions of ecosystems.[22]

The sustainability movement has gained momentum over the last two decades, with interest from all sectors increasing rapidly each year. In the book Regenerative Development and Design: A Framework for Evolving Sustainability, the Regenesis Group asserts that the sustainability "debate is shifting from whether we should work on sustainability to how we're going to get it done." Sustainability was first viewed as a "steady state of equilibrium" in which there was a balance between inputs and outputs with the idea that sustainable practices meant future resources were not compromised by current processes. As this idea of sustainability and sustainable building has become more widely accepted and adopted, the idea of "net-zero" and even "net-positive" have become topics of interest. These relatively newer concepts focus on positively impacting the surrounding environment of a building rather than simply reducing the negative impacts.[23]

Regenerative design

J.T. Gibberd argued "a building is an element set within wider human endeavors and is necessarily dependent on this context. Thus, a building can support sustainable patterns of living, but in and of itself cannot be sustainable"[24] Regenerative design goes a step further than sustainable design. In a regenerative system, feedback loops allow for adaptability, dynamism and emergence to create and develop resilient and flourishing eco-systems. Cole highlights a key distinction of regenerative design is the recognition and emphasis of the "co-evolutionary, partnered relationship between human and natural systems" and thus importance of project location and place.[21] Bruno Duarte Dias asserts that regenerative design goes beyond the traditional weighing and measuring of various environmental, social and economic impacts of sustainable design and instead focuses on mapping relationships. Dias is in agreement with Cole stating three fundamental aspects of regenerative design which include: understanding place and its unique patterns, designing for harmony within place, and co-evolution.

Fundamental aspects

Co-evolution of humans and nature

Regenerative design is built on the idea that humans and the built environment exist within natural systems and thus, the built environment should be designed to co-evolve with the surrounding natural environment. Dias asserts that a building should serve as a “catalyst for positive change.” The project does not end with the completion of construction and certificate of occupancy, instead the building serves to enhance the relationships between people, the built environment and the surrounding natural systems over a long period of time.

Designing in context of place

Understanding the location of the project, the unique dynamics of the site and the relationship of the project to the living natural systems is a fundamental concept in the regenerative design process. In their article Designing from place: a regenerative framework and methodology, Pamela Mang and Bill Reed define place as a "unique, multilayered network of living systems within a geographic region that results from the complex interactions, through time, of the natural ecology (climate, mineral and other deposits, soil, vegetation, water and wildlife, etc.) and culture (distinctive customs, expressions of values, economic activities, forms of association, ideas for education, traditions, etc.)"[25] A systems-based approach to design in which the design team looks at the building within the larger system is crucial.

Gardener analogy

Beatrice Benne and Pamela Mang emphasize the importance of the distinction between working with a place rather than working on a place within the regenerative design process. They use an analogy of a gardener to re-define the role of a designer in the building process. "A gardener does not 'make' a garden. Instead, a skilled gardener is one who has developed an understanding of the key processes operating in the garden" and thus the gardener "makes judicious decisions on how and where to intervene to reestablish the flows of energy that are vital to the health of the garden."[26] In the same way a designer does not create a thriving ecosystem rather they make decisions that indirectly influence whether the ecosystem degrades or flourishes over time. This requires designers to push beyond the prescriptive and narrow way of thinking they have been taught and use complex systems thinking that will be ambiguous and overwhelming at times. This includes accepting that the solutions do not exclusively lie in technological advancements and are instead a combination of sustainable technologies and an understanding of the natural flow of resources and underlying ecological processes. Benne and Mang identify these challenges and state the most difficult of these will be shifting from a mechanistic to an ecological worldview. The tendency is to view building as the physical processes of the structure rather than the complex network of relationships the building has with the surrounding environment including the natural systems and the human community.[26]

Conservation vs. preservation

Regenerative design places more importance on conservation and biodiversity rather than on preservation. It is recognized in regenerative design that humans are a part of natural ecosystems. To exclude people is to create dense areas that destroy pockets of existing ecosystems while preserving pockets of ecosystems without allowing them to change naturally over time.

Regenerative design frameworks

There are a few regenerative design frameworks that have been developed in recent years. Unlike many green building rating systems, these frameworks are not prescriptive checklists. Instead they are conceptual and meant to guide dialogue throughout the design process. They should not be used exclusively rather in conjunction with existing green building rating systems such as LEED, BREEAM or Living Building Challenge.[27]

Living Building Challenge

The Living Building Challenge is an international sustainable building certification program launched in 2006 by the non-profit International Living Future Institute. It is described by the Institute as a philosophy, advocacy tool and certification program that promotes the most advanced measurement of sustainability in the built environment. It can be applied to development at all scales, from buildings—both in new constructions and renovations—to infrastructure, landscapes, neighborhoods and communities, and differs from other green certification schemes such as LEED or BREEAM). It was created by Jason F. McLennan and Bob Berkebile, of BNIM. McLennan brought the program to Cascadia when he became its CEO in 2006. The International Living Building Institute was founded by McLennan and Cascadia in May 2009 to oversee the Living Building Challenge and its auxiliary programs and later renamed the International Living Future Institute.

The intention of the Living Building Challenge is to encourage the creation of a regenerative built environment. The challenge is an attempt to raise the bar for building standards from doing less harm to contributing positively to the environment. It "acts to rapidly diminish the gap between current limits and the end-game positive solutions we seek" by pushing architects, contractors, and building owners out of their comfort zones.

SPeAR

Sustainable Project Appraisal Routine (SPeAR) is a decision-making tool developed by software and sustainability experts at Arup. The framework incorporates key categories including transportation, biodiversity, culture, employment and skills.[28]

REGEN

The regenerative design framework REGEN was proposed by Berkebile Nelson Immenschuh McDowell (BNIM), a US architectural firm, for the US Green Building Council (USGBC).[21] The tool was intended to be a web-based, data-rich framework to guide dialogue between professionals in the design and development process as well as "address the gap in information and integration of information."[29] The framework has three components:[29]

- Framework – the framework encourages systems thinking and collaboration as well as linking individual strategies to the goals of the project as a whole

- Resources – the framework includes place-based data and information for project teams to use

- Projects – the framework includes examples of successful projects that have incorporated regenerative ideas into the design as models for project teams

LENSES

Living Environments in Natural, Social and Economic Systems (LENSES)[30] was created by Colorado State University's Institute for the Built Environment. The framework is intended to be process-based rather than product-based. The goals of the framework include:[21]

- to direct the development of eco-regional guiding principles for living built environments

- to illustrate connections and relationships between sustainability issues

- to guide collaborative dialogue

- to present complex concepts quickly and effectively to development teams and decision-makers

The framework consists of three "lenses": Foundational Lens, Aspects of Place Lens and Flows Lens. The lenses work together to guide the design process, emphasizing the guiding principles and core values, understanding the delicate relationship between building and place and how elements flow through the natural and human systems.[21]

McLennan Design

Founded in 2013 by global sustainability leader and green design pioneer Jason F. McLennan, McLennan Design is a world leader in net zero energy, multi-disciplinary, regenerative design practices, focused on deep green outcomes in the fields of architecture, planning, consulting, and product design. They use an ecological perspective to drive design creativity and innovation.

McLennan Design is an architecture firm solely dedicated to its practice to the creation of Living Buildings, net-zero, and regenerative projects all over the world. Their architecture and consulting work allows us to affect change across multiple industries, guiding leading institutions and corporations around the globe to rethink their impact on the environment and the world around them. McLennan has stated, “Regenerative Design is a philosophical approach to design whereby we look to enhance the conditions for all of life – both people and other species. We want the net result of our design work to be greater ecological, social and cultural health.”

Perkins+Will

Perkins+Will is a global architecture and design firm with a strong focus on sustainability – by September 2012 the firm had completed over 150 LEED-certified projects.[31] It was at the 2008 Healthcare Center for Excellence meeting in Vancouver, British Columbia that the decision was made to develop a regenerative design framework in an effort to generate broader conversation and inspirational ideas.[32] Later that year, a regenerative design framework that could be used by all market sectors including healthcare, education, commercial and residential was developed by Perkins+Will in conjunction with the University of British Columbia. The framework had four primary objectives:[32]

- to initiate a different and expanded dialogue between the design team members and with the client and users, moving beyond the immediate building and site boundaries

- to emphasize the opportunities of developed sites and buildings to relate to, maintain, and enhance the health of the ecological and human systems in the place in which they are situated

- to highlight the ecological and human benefits that accrue from regenerative approaches

- to facilitate the broader integration of allied design professionals – urban planners, landscape architects and engineers, together with other disciplines (ecologists, botanists, hydrologists, etc.) typically not involved in buildings – in an interdisciplinary design process

The structure of the framework consists of four primary themes:[32]

- Representation of human and natural systems – the framework is representative of the interactions between humans and the natural environment and is built on the notion that human systems exist only within natural systems. Human needs are further categorized into four categories: individual human health and well-being, social connectivity and local community, cultural vitality and sense of place, and healthy community.[32]

- Representation of resource flows – the framework recognizes that human systems and natural systems are impacted through the way building relates to the land and engages resource flows. These resource flows include energy, water and materials.[32]

- Resource cycles – within the framework, resource flows illustrate how resources flow in and out of human and natural cycles whereas resource cycles focus on how resources move through human systems. The four sub-cycles included in the framework are produce, use, recycle and replenish.[32]

- Direct and indirect engagement with flows – the framework distinguishes between the direct and indirect ways a building engages with resource flows. Direct engagement includes approaches and strategies that occur within the bounds of the project site. Indirect engagement extends beyond the boundaries of the project site and can thus be implemented on a much larger scale such as purchasing renewable energy credits.[32]

Case study – VanDusen Botanical Garden

The Visitor Centre at the VanDusen Botanical Garden in Vancouver, British Columbia was designed in parallel with the regenerative design framework developed by Perkins+Will. The site of the new visitor center was 17,575 m2 and the building itself 1,784 m2.[32] A four stage process was identified and included: education and project aspirations, goal setting, strategies and synergies, and whole systems approaches. Each stage raises important questions that require the design team to define place and look at the project in a much larger context, identify key resources flows and understand the complex holistic systems, determine synergistic relationships and identify approaches that provoke the coevolution of both humans and ecological systems.[32] The visitor centre was the first project that Perkins+Will worked on in collaboration with an ecologist. Incorporating an ecologist on the project team allowed the team to focus on the project from a larger scale and understand how the building and its specific design would interact with the surrounding ecosystem through its energy, water and environmental performance.[33]

For retrofitting existing buildings

Importance and implications

It is said that the majority of buildings estimated to exist in the year 2050 have already been built.[34] Additionally, current buildings account for roughly 40 percent of the total energy consumption within the United States.[35] This means that in order to meet climate change goals – such as the Paris Agreement on Climate Change – and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, existing buildings need to be updated to reflect sustainable and regenerative design strategies.

Strategies

Craft et al. attempted to create a regenerative design model that could be applied to retrofitting existing buildings. This model was prompted by the large number of currently existing buildings projected to be present in 2050. The model presented in this article for building retrofits follows a 'Levels of Work' framework consisting of four levels that are said to be pertinent in increasing the "vitality, viability and capacity for evolution" which require a deep understanding of place and how the building interacts with the natural systems. These four levels are classified as either proactive or reactive and include regenerate, improve, maintain and operate.[34]

Case study

University of New South Wales

Craft et al. present a case study in which the chemical science building at the University of New South Wales was retrofitted to incorporate these regenerative design principles. The strategy uses biophilia to improve occupants health and wellbeing by strengthening their connection to nature. The facade acts as a "vertical ecosystem" by providing habitats for indigenous wildlife to increase biodiversity. This included the addition of balconies to increase the connection between humans and nature.[34]

Regenerative agriculture

Regenerative farming or 'regenerative agriculture' calls for the creation of demand on agricultural systems to produce food in a way that is beneficial to the production and the ecology of the environment. It uses the science of systems ecology, and the design and application through permaculture. As understanding of its benefits to human biology and ecological systems that sustain us is increased as has the demand for organic food. Organic food grown using regenerative and permaculture design increases the biodiversity and is used to develop business models that regenerate communities. Whereas some foods are organic some are not strictly regenerative because it is not clearly seeking to maximize biodiversity and the resilience of the environment and the workforce. Regenerative agriculture grows organic produce through ethical supply chains, zero waste policies, fair wages, staff development and wellbeing, and in some cases cooperative and social enterprise models. It seeks to benefit the staff along the supply chain, customers, and ecosystems with the outcome of human and ecological restoration and regeneration.

Size of regenerative systems

The size of the regenerative system affects the complexity of the design process. The smaller a system is designed the more likely it is to be resilient and regenerative. Multiple small regenerative systems that are put together to create larger regenerative systems help to create supplies for multiple human-inclusive-ecological systems.

See also

References

- ↑ Ikerd, John (2021). "The Realities of Regenerative Agriculture". Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development. 10 (2). doi:10.5304/jafscd.2021.102.001. S2CID 234037904.

- ↑ Tillman Lyle, John (2017). Regenerative Design for Sustainable Development.

- ↑ Melby, Pete; Cathcart, Thom (2002). Regenerative Design Techniques: Practical Applications in Landscape Design. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 9780471414728.

- ↑ Wahl, Daniel Christian (2016). Designing Regenerative Cultures. Triarchy Press. ISBN 9781909470798.

- ↑ Loring, Philip (2022). "Regenerative Food Systems and the Conservation of Change". Agriculture and Human Values. 39 (2): 701–713. doi:10.1007/s10460-021-10282-2. PMC 8576312. PMID 34776604.

- ↑ "Permaculture magazine". 2016-06-18. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- ↑ Diebold, William; Alperovitz, Gar; Faux, Jeff (1984). "Rebuilding America: A Blueprint for the New Economy". Foreign Affairs. 63 (1): 190. doi:10.2307/20042109. ISSN 0015-7120. JSTOR 20042109.

- ↑ Holmgren and Mollison (1978). Permaculture One. Transworld Publishers. p. 128. ISBN 978-0552980753.

- ↑ King, Franklin Hiram (1911). Farmers of Forty Centuries: Or Permanent Agriculture in China, Korea and Japan.

- ↑ Paull , John (2011) The making of an agricultural classic: Farmers of Forty Centuries or Permanent Agriculture in China, Korea and Japan, 1911–2011, Agricultural Sciences, 2 (3), pp. 175–180.

- ↑ Dargavel, John; Mulligan, Martin; Hill, Stuart (July 2003). "Ecological Pioneers: A Social History of Australian Ecological Thought and Action". Environmental History. 8 (3): 481. doi:10.2307/3986208. ISSN 1084-5453. JSTOR 3986208.

- 1 2 3 Rodale Institute. "Regenerative Organic Agriculture and Climate Change: A Down-to-Earth Solution to Global Warming" (PDF). rodaleinstitute.org. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- 1 2 "History of the Lyle Center | Lyle Center for Regenerative Studies | College of Environmental Design – Cal Poly Pomona". env.cpp.edu. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- ↑ Lyle, John Tillman (1994). Regenerative Design for Sustainable Development. John Wiley.

- ↑ Petersen, John E. (Winter 2011). "Case Study: Oberlin College's Early Adopter" (PDF). High Performing Buildings.

- ↑ McDonough, William; Braungart, Michael (2002). Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things. New York: North Point Press. ISBN 978-0-86547-587-8.

- ↑ "Cradle to Cradle". www.product-life.org. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- ↑ "Sim Van der Ryn". Sim Van der Ryn. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- ↑ "Author". Sim Van der Ryn. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- ↑ Wahl, Daniel Christian. "Sustainability is not enough: we need regenerative cultures". Retrieved 26 January 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cole, Raymond (2012). "Transitioning from green to regenerative design". Building Research & Information. 40: 39–53. doi:10.1080/09613218.2011.610608. S2CID 109890223.

- 1 2 Orr, David (1992). Ecological Literacy: Education and the Transition to a Postmodern World. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, Albany. ISBN 978-0-7914-0873-5.

- ↑ Mang, Pamela; Haggard, Ben; Regenesis (2016). Regenerative Development and Design: A Framework for Evolving Sustainability. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

- ↑ Gibberd, J.T. (2001). "The opinion of Gibberd". Sustainable Building. 3: 41.

- ↑ Mang, Pamela; Reed, Bill (2011). "Designing from place: a regenerative framework and methodology". Building Research & Information. 40: 23–38. doi:10.1080/09613218.2012.621341. S2CID 55843766.

- 1 2 Mang, Pamela; Benne, Beatrice (2015). "Working regeneratively across scales – insights from nature applied to the built environment". Journal of Cleaner Production. 109: 42–52. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.02.037.

- ↑ Gou, Zhonghua; Xie, Xiaohuan (2017). "Evolving green building: triple bottom line or regenerative design?". Journal of Cleaner Production. 153: 600–607. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.02.077.

- ↑ "SPeAR (Sustainable Project Appraisal Routine)". Arup.

- 1 2 Svec, Phaedra; Berkebile, Robert; Todd, Joel Ann (2011). "REGEN: toward a tool for regenerative thinking". Building Research & Information. 40: 81–94. doi:10.1080/09613218.2012.629112. S2CID 111116840.

- ↑ "LENSES".

- ↑ joelregister (2012-09-28). "Perkins+Will Designs More Than 150 LEED-Certified Projects". Global. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Cole, Raymond J.; Busby, Peter; Guenther, Robin; Briney, Leah; Blaviesciunaite, Aiste; Alencar, Tatiana (2011). "A regenerative design framework: setting new aspirations and initiating new discussions". Building Research & Information. 40: 95–111. doi:10.1080/09613218.2011.616098. S2CID 109142811.

- ↑ Busby, Peter; Richter, Max; Driedger, Michael (2011). "Towards a New Relationship with Nature: Research and Regenerative Design in Architecture". Architectural Design. 81 (6): 92–99. doi:10.1002/ad.1325.

- 1 2 3 Craft, W; Ding, L; Prasad, D; Partridge, L; Else, D (2017). "Development of a Regenerative Design Model for Building Retrofits". Procedia Engineering. 180: 658–668. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2017.04.225.

- ↑ "Retrofitting Existing Buildings to Improve Sustainability and Energy Performance | WBDG – Whole Building Design Guide". www.wbdg.org. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

External links

- Design for Human Ecosystems

- John T. Lyle Center for Regenerative Studies

- Regenesis Group

- Soil Symbiotics

- Harmonic Ecological Design

- Regenerative Design Group

- Regenerative Design Institute

- Regenerative Architecture

- Center for Maximum Potential Building Systems

- Regenerative Design for Sustainable Development

- Regenerative Development Centre Chile