| Rochdale Town Hall | |

|---|---|

The Town Hall, in 2008 | |

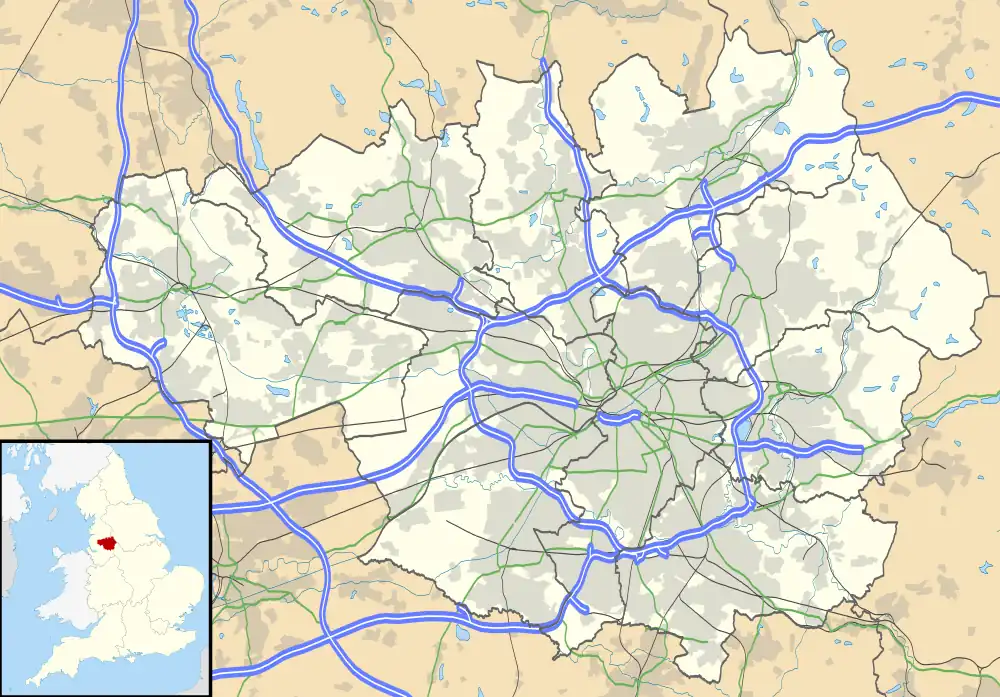

Shown within Greater Manchester | |

| Former names | Rochdale Town Hall and Police G.V. I Station |

| General information | |

| Type | Town hall |

| Architectural style | Victorian, Gothic Revival |

| Location | Rochdale Greater Manchester England |

| Address | The Esplanade ROCHDALE OL16 1AZ |

| Coordinates | 53°36′56″N 2°09′34″W / 53.6156°N 2.1594°W |

| Current tenants | Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council |

| Construction started | 31 March 1866 |

| Inaugurated | 27 September 1871 |

| Destroyed | 10 April 1883 (tower) |

| Cost | £160,000 (£15,850,000) |

| Owner | Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council |

| Height | 190 feet (58 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 3[1] |

| Floor area | 3,000 square yards (2,500 m2)[2] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | William Henry Crossland, Alfred Waterhouse (clock tower only) |

| Other designers | Rochdale Corporation |

| Main contractor | W. A. Peters and Son[3] |

| Awards and prizes | Grade I listed building |

| References | |

| [4][5][6] | |

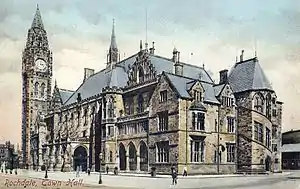

Rochdale Town Hall is a Victorian-era municipal building in Rochdale, Greater Manchester, England. It is "widely recognised as being one of the finest municipal buildings in the country",[4] and is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade I listed building.

The Town Hall functions as the ceremonial headquarters of Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council and houses local government departments, including the borough's civil registration office.

Built in the Gothic Revival style at a cost of £160,000 (£15.9 million in 2024),[7] it was inaugurated for the governance of the Municipal Borough of Rochdale on 27 September 1871.

The architect, William Henry Crossland, was the winner of a competition held in 1864 to design a new Town Hall. It had a 240-foot (73 m) clock tower topped by a wooden spire with a gilded statue of Saint George and the Dragon, both of which were destroyed by fire on 10 April 1883, leaving the building without a spire for four years.

A new 190-foot (58 m) stone clock tower and spire in the style of Manchester Town Hall was designed by Alfred Waterhouse, and erected in 1887.

Architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner described the building as possessing a "rare picturesque beauty".[8] Its stained-glass windows are credited as "the finest modern examples of their kind".[4]

The building came to the attention of Adolf Hitler, who was said to have admired it so much that he wished to ship the building, brick-by-brick, to Nazi Germany had the United Kingdom been defeated in the Second World War.[9]

History

Rochdale had developed into an increasingly large, populous, and prosperous urban mill town since the Industrial Revolution. Its newly built rail and canal network, and numerous factories, resulted in the town being "remarkable for many wealthy merchants".[10] In January 1856 the electorate of the Rochdale constituency petitioned the Privy Council for the grant of a charter of incorporation under the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, to constitute the town as a municipal borough. This would give it limited political autonomy via an elected town council, comprising a mayor, aldermen, and councillors, to oversee local affairs.[11]

The petition was successful and the charter was granted in September 1856.[12] The newly formed Rochdale Corporation—the local authority for the Municipal Borough of Rochdale—suggested plans to build a town hall in which to conduct its business in May 1858.[2][3] The site of an abandoned 17th century house known as the Wood was proposed. Six months later, in April 1860, Rochdale Corporation arranged to buy the site on the outskirts of the town centre for £4,730 (£504,000 in 2024).[7] However, plans were shelved due to lengthy negotiations and increasing land prices. In January 1864 the scheme resumed with a new budget of £20,000 (£1,990,000 in 2024).[7][3]

The wood and surrounding area were cleared, but it is unknown what became of the dispossessed; there was no legal requirement for the authorities to rehouse the former inhabitants.[13] A design competition to find a "neat and elegant building" was held by the Rochdale Corporation,[14] who offered the winning architect a prize of £100 (£10,500 in 2024),[7] and a Maltese cross souvenir. From the 27 entries received, William Henry Crossland's was chosen.[2][5] The Rochdale-born Radical and Liberal statesman John Bright laid the foundation stone on 31 March 1866. Construction was complete by 1871 although the cost had, by then, increased beyond expectations from the projected £40,000[15] to £160,000 (£15,850,000 in 2024).[7][2][6][16]

The Town Hall was one of several built in the textile towns of North West England following the Municipal Corporations Act 1835, but is one of only two in Greater Manchester built in the Gothic style. Between the setting of the foundation stone and the building's completion, revisions and additions were made to the original design. Money was "lavished" upon the decor and inventory, and the extra expenditure did not escape the ire of its critics.[2]

The cost of the building increased year-on-year through a combination of mismanagement, overspending and "unauthorised work".[14] Public criticism of the high cost was aimed at Crossland and the Mayor of Rochdale, George Leach Ashworth, who oversaw the work.[3][17] Nevertheless, Rochdale Town Hall was ultimately celebrated as "a source of pride", and its completion prompted celebration and rejoicing;[2] it transformed a "derelict and marshy riverbank in to a huge romantic Gothic plaza".[13] The opening ceremony on 27 September 1871 was performed by Mayor Ashworth, who had been instrumental in the changes made to the building's design.[2]

In 1882 or 1883[18] dry rot was found in the 240-foot (73 m) high spire. On the recommendation of Rochdale's Borough Surveyor, contractors were engaged to rebuild it.[2][3] The spire was to be demolished to clear the way for a replacement. It was rumoured that the workmen who were dismantling the top section of the wooden spire may have tried to speed up the dismantling process with matches and, at 9:20 am on 10 April 1883, a blaze was discovered. Despite the efforts of volunteers and the local fire brigade, 100 minutes after the discovery of the fire the entire spire, including a statue of Saint George and the Dragon, had been destroyed.[19]

The cause of the fire was never established,[2] but Rochdale's fire service was criticised for taking longer to respond to the blaze than Oldham's (based 5 miles (8 km) south), despite the Rochdale Fire Brigade being based in the Town Hall.[3] Alfred Waterhouse was given the task of designing a 190-foot (58 m) stone replacement.[3] His work on the clock tower, which was built between 1885 and 1887[3] about 15 yards (14 m) further to the east than the original,[2] shows many similarities to Manchester Town Hall,[3] which he also designed.[20] The tower was opened in 1887;[5] an inscribed plaque commemorates the fire of 1883.[3]

On 15 January 1931, at the height of the Great Depression in the United Kingdom, the Territorial Army was called to guard the Town Hall during a protest against unemployment and hunger.[21]

In May 1938, Rochdale-born actress, singer and comedian Gracie Fields was granted Honorary Freedom of the Borough for her contribution to entertainment. "When the ceremony was over, Gracie went onto the town hall balcony to receive the cheers and good wishes of the thousands of people who were packing the streets below."[22]

Although it is not fully understood how it came to his attention, Rochdale Town Hall was admired by Adolf Hitler.[23][24] It has been suggested a visit by Hitler in 1912–13 while staying with his half-brother Alois Hitler Jr. in Liverpool, or military intelligence on Rochdale, or information from Nazi sympathiser William Joyce (who had lived in Oldham), brought the building to his attention. Hitler admired the architecture so much that it is believed he wished to ship the building, brick-by-brick, to Nazi Germany had German-occupied Europe encompassed the United Kingdom. Rochdale was broadly avoided by German bombers during the Second World War.[23][24]

Features

Location

At OS Grid Reference SD895132 (53.6156°, −2.1594°), Rochdale Town Hall is the centerpiece of Rochdale, located in Town Hall Square to the south of The Esplanade and the River Roch.[2][25] The Parish Church of St Chad is situated by the wooded hillside behind the Town Hall.[25] In Town Hall Square, opposite the Town Hall, is a statue of John Bright, dated 1891, and the Rochdale War Memorial. Bright was a Rochdale-born orator, pacifist and Member of Parliament for Birmingham known for his campaigns to repeal the Corn Laws as well as his opposition to slavery in the United States and the Crimean War.[26] Touchstones Rochdale art gallery and local studies centre is across The Esplanade.[26]

Exterior and layout

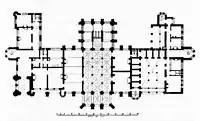

The frontage and principal entrance of the Town Hall face the River Roch,[1] and comprises a portico of three arches intersected by buttresses. Decorating the main entrance are stone crockets, gargoyles, and finials. Four gilded lions above a parapet around three sides of the portico bear shields carrying the coats of arms of Rochdale Council and the hundred of Salford.[2]

Rochdale Town Hall is 264 feet (80 m) wide, 123 feet (37 m) deep, and is faced with millstone grit quarried from Blackstone Edge and Todmorden.[2] Although now blackened by industrial pollution, the building has been described as a "rich example of domestic Gothic architecture".[2] Naturalistic carved foliage on the exterior recalls the style of Southwell Minster,[5] and the architecture is influenced by Perpendicular Period and medieval town halls of continental Europe.[2]

The building has been likened to Manchester Town Hall, Manchester Assize Courts, the Royal Courts of Justice, and St Pancras railway station, all products of the Gothic Revival architectural movement.[2] The stained glass windows, some of which were designed by William Morris,[5] have been described as "the finest modern examples of their kind".[4] At each end of the frontage is an octagonal staircase.[1]

In the words of Nikolaus Pevsner, Rochdale Town Hall has "a splendidly craggy exterior of blackened stone".[16] The building has a roughly symmetrical E-shaped plan, and is broken down into three self-contained segments: a central Great Hall and transverse wings at each end, which have variously been used as debating chambers, corporation-rooms, trade and a public hall.[1]

The south-east wing used to house the magistrates' courts, and the north-west wing the mayor's rooms. In the north-east is a tower. Access to the main entrance is through a central porte cochere.[27] The façade extends across 14 bays, of which the Great Hall accounts for seven. On both sides, the outermost bays rise to three storeys. They flank asymmetric round-headed arcades—two to the left and three to the right, all of single-storey height—which sit below plain mullioned windows, balconies and ornately decorated gables.[5]

Clock tower

The original clock tower contained 13 bells, by John Taylor & Co of Loughborough,[28] together with a clock and carillon machine (by Gillett, Bland & Co.) which played 14 different tunes on the bells.[29] These were all destroyed in the 1883 fire.[3]

The present clock tower, which has a stone spire, was built to replace the one destroyed in the fire. It was designed by Alfred Waterhouse in a similar style to one of his earlier works, the clock tower of Manchester Town Hall. The first stone was laid by Thomas Schofield JP, Alderman and Rochdale Borough Councillor, on 19 October 1885 and the tower was declared complete on 20 June 1887, the Golden Jubilee of Queen Victoria. It was fitted with five bells (again by Taylor),[28] which ring on the hour and at 15-minute intervals, and a Cambridge-chiming clock by Potts & Sons, which was set going in November of that year.[30]

The tower rises from a plinth and has four stages including the gable-headed clock stage, which is also decorated with pinnacles. A small stone spire completes the composition.[5] The design of the original tower was more elaborate and 50 feet (15 m) higher than its successor, which is 190 feet (58 m) tall.[2]

Interior

Murals in the former council chamber depict the inventions that drove the Industrial Revolution,[31] and the Great Hall is adorned with a large fresco of the signing of Magna Carta by artist Henry Holiday, although the painting is dirty.[8] Responsibility for the decoration of the interior was given to Heaton, Butler and Bayne, who incorporated floor tiles that were manufactured by Mintons and decorated with the local insignia and the Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom.[32]

The stone Grand Staircase, which leads from the vestibule to the Great Hall, is decorated with stained glass; such glass windows decorate most of the Town Hall and are considered to be the finest example of the work of Heaton, Butler and Bayne.[33][34] The medieval style Great Hall, described by Pevsner as a room of "great splendour and simplicity",[34] has a hammerbeam roof flanked by statues of angels, in a design that resembles Westminster Hall.[4]

James Jepson Binns built the town hall's pipe organ in 1913; it was rebuilt in 1979 by J.W. Walker & Sons Ltd.[35]

Heritage status and function

The Town Hall was listed at Grade I on 25 October 1951.[5] Such buildings are defined as being of "exceptional interest, sometimes considered to be internationally important".[36]

In February 2001, it was one of 39 Grade I listed buildings, and 3,701 listed buildings of all grades, in Greater Manchester.[37] Within the Metropolitan Borough of Rochdale, it is one of only three Grade I listed buildings, and 312 listed buildings of all grades.[38]

Although the majority of local government functions now take place within Number One Riverside, Rochdale Town Hall continues to be used for cultural and ceremonial functions. For instance, it is used for the Metropolitan Borough of Rochdale's mayoralty,[39] civil registry,[40][41][42] and for formal naturalisation in British Citizenship ceremonies.[43][44]

See also

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 Great Britain Historical GIS Project (2004), "Descriptive Gazetteer Entry for ROCHDALE", A vision of Britain through time, University of Portsmouth, retrieved 18 January 2010

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Rochdale Boroughwide Community Trust, Rochdale Town Hall, link4life.org, retrieved 17 January 2010

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Public Monuments and Sculpture Association (16 June 2003), Rochdale Town Hall, pmsa.cch.kcl.ac.uk, archived from the original on 25 July 2011, retrieved 21 January 2010

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council & N.D., p. 43.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Historic England, "Town Hall, Rochdale (1084275)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 12 September 2013

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - 1 2 Godman 2005, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- 1 2 Hartwell, Hyde & Pevsner 2004, p. 59.

- ↑ "Preserving the Rochdale Reichstag". BBC. 15 September 2009. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ↑ Godman 2005, p. 7.

- ↑ "No. 21845". The London Gazette. 1 February 1856. p. 365.

- ↑ "Rochdale's Charter of Incorporation (and letters)". link4life.org. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- 1 2 Cunningham 1981, p. 175.

- 1 2 Garrard 1983, p. 81.

- ↑ "Rochdale Town Hall: Laying of the cornerstone by Mr. Bright M.P.", The Leeds Mercury, p. 2, 2 April 1866

- 1 2 Hartwell, Hyde & Pevsner 2004, p. 594.

- ↑ "George Leach Ashworth (1823–1873)". Art UK. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ↑ Rochdale Boroughwide Community Trust, Rochdale Town Hall, link4life.org, retrieved 17 January 2010 gives the year as 1882 whereas "The 1880s", Rochdale Observer, rochdaleobserver.co.uk, 13 June 2003, retrieved 16 January 2010 states 1883.

- ↑ "The 1880s", Rochdale Observer, M.E.N. Media, 11 June 2003, retrieved 16 January 2010

- ↑ Cunningham, Colin (2004), "Waterhouse, Alfred (1830–1905)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, retrieved 25 July 2011

- ↑ Marwick 2000, p. 110.

- ↑ Moules 1983, pp. 77–78.

- 1 2 "Amazing windows always a glass act", Rochdale Observer, M.E.N. Media, 7 October 2006, retrieved 22 December 2007

- 1 2 "Preserving the Rochdale Reichstag", BBC News, 15 September 2009, retrieved 16 January 2010

- 1 2 Hardy 2005, p. 50.

- 1 2 Industrial Powerhouse (NWDA) (August 2006), Rochdale Heritage Trail (PDF), industrialpowerhouse.co.uk, retrieved 21 January 2010

- ↑ Hartwell, Hyde & Pevsner 2004, pp. 594–595.

- 1 2 Snowdon, Jasper W. (1888). Grandsire: the Method, Its Peals, and History. London: Wells Gardner, Darton & Co. p. 207.

- ↑ Pickford, Chris, ed. (1995). Turret Clocks: Lists of Clocks from Makers' Catalogues and Publicity Materials (2nd ed.). Wadhurst, E. Sussex: Antiquarian Horological Society. p. 84.

- ↑ Potts, Michael S. (2006). Potts of Leeds: Five Generations of Clockmakers. Ashbourne, Derbyshire: Mayfield Books. p. 92.

- ↑ Hartwell, Hyde & Pevsner 2004, p. 46.

- ↑ Fawcett 1998, p. 135.

- ↑ Hartwell, Hyde & Pevsner 2004, p. 71.

- 1 2 Hartwell, Hyde & Pevsner 2004, p. 595.

- ↑ "A Short History of Rochdale Town Hall Organ". Oldham Rochdale & Tameside Organists' Association. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ↑ "Listed Buildings". Historic England. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ English Heritage (2007), "Images of England — Statistics by County", Images of England, imagesofengland.org.uk, archived from the original on 12 November 2007, retrieved 16 January 2010

- ↑ English Heritage (2007), "Images of England — Statistics by County (Greater Manchester)", Images of England, imagesofengland.org.uk, archived from the original on 26 December 2007, retrieved 16 January 2010

- ↑ Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council, Mayor Information, rochdale.gov.uk, retrieved 22 January 2010

- ↑ Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council, Copy certificates for births, deaths and marriages, rochdale.gov.uk, retrieved 22 January 2010

- ↑ Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council, Family History, rochdale.gov.uk, retrieved 22 January 2010

- ↑ Greater Manchester County Records Office, Register Offices in Greater Manchester, gmcro.co.uk, archived from the original on 4 June 2008, retrieved 22 January 2010

- ↑ Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council, Citizenship Ceremonies, rochdale.gov.uk, archived from the original on 28 August 2009, retrieved 22 January 2010

- ↑ Byrne, Michael (26 April 2004), "New citizens are proud to be Brits", Rochdale Observer, M.E.N. Media, retrieved 22 January 2010

Bibliography

- Cunningham, Colin (1981), Victorian and Edwardian Town Halls, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7100-0723-0

- Fawcett, Jane (1998), Historic Floors: Their History and Conservation, Butterworth-Heinemann, ISBN 978-0-7506-2765-8

- Garrard, John (1983), Leadership and Power in Victorian Industrial Towns, 1830–80, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-0897-9

- Godman, Pam (2005), Rochdale, Nonsuch Publishing, ISBN 978-1-84588-173-3

- Hardy, Clive (2005), Greater Manchester: Photographic Memories, The Francis Firth Collection, ISBN 978-1-85937-266-1

- Hartwell, Clare; Hyde, Matthew; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2004) [1969], The Buildings of England: Lancashire: Manchester and the South-East, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-10583-5

- Marwick, Arthur (2000), History of the Modern British Isles, 1914–1999: Circumstances, Events, and Outcomes, Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-631-19522-1

- Moules, Joan (1983), Our Gracie: The Life of Dame Gracie Field, Robert Hale, ISBN 0-7090-1010-9

- Rochdale Metropolitan Borough Council, Metropolitan Rochdale Official Guide, Ed. J. Burrow & Co.

External links

- Organ performance - Richard Wagner's Ride of the Valkyries (German: Walkürenritt or Ritt der Walküren) 5m20s

.JPG.webp)