| Clan Munro | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Clann an Rothaich[1] | |||

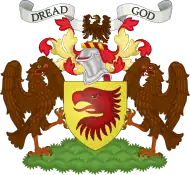

Crest: An eagle perching Proper | |||

| Motto | Dread God[2] | ||

| War cry | Caisteal Folais 'na Theine | ||

| Profile | |||

| Region | Highland | ||

| District | Easter-Ross[2] | ||

| Plant badge | Common club moss[2] | ||

| Pipe music | Bealach na Broige[2] | ||

| Chief | |||

| |||

| Hector Munro of Foulis[2] | |||

| The 35th Chief of Clan Munro (Tighearna Foghlais[1]) | |||

| Seat | Foulis Castle | ||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

Clan Munro (ⓘ; Scottish Gaelic: Clann an Rothaich [ˈkʰl̪ˠãũn̪ˠ ə ˈrˠɔhɪç]) is a Highland Scottish clan. Historically the clan was based in Easter Ross in the Scottish Highlands. Traditional origins of the clan give its founder as Donald Munro who came from the north of Ireland and settled in Scotland in the eleventh century, though its true founder may have lived much later.[5] It is also a strong tradition that the Munro chiefs supported Robert the Bruce during the Wars of Scottish Independence. The first proven clan chief on record however is Robert de Munro who died in 1369; his father is mentioned but not named in a number of charters. The clan chiefs originally held land principally at Findon on the Black Isle but exchanged it in 1350 for Estirfowlys. Robert's son Hugh who died in 1425 was the first of the family to be styled "of Foulis", despite which clan genealogies describe him as 9th baron.

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the Munros feuded with their neighbors the Clan Mackenzie, and during the seventeenth century many Munros fought in the Thirty Years' War in support of Protestantism. During the Scottish Civil War of the seventeenth century different members of the clan supported the Royalists and Covenanters at different times. The Munro chiefs supported the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and during the Jacobite risings of the eighteenth century the clan and the chiefs were staunchly anti-Jacobite, supporting the Hanoverian-British Government.

History

Origins

Traditional origins

Traditionally the Munros came from Ireland and settled in Scotland in the 11th century under chief Donald Munro, son of Ó Catháin or O'Kain, an Irish chief.[6] Donald Munro was granted lands for services rendered to Malcolm II of Scotland in defeating the Danes (Vikings).[7] From this Donald Munro the clan lands have since been known as Ferindonald, meaning Donald's lands.[8][6] Ferindonald is a narrow strip of land running for eight miles along the northern shore of the Cromarty Firth from Dingwall to Alness.[9] There were also small pockets of Munros in Sutherland in the far north,[10] and some Munros established themselves south of the Cromarty Firth on the Black Isle.[10]

According to the same traditional sources Donald Munro's grandson, Hugh Munro, was the first Munro to be authentically designated Baron of Foulis; he died in 1126. A reliable scholar, Alexander Nisbet, stated that George Munro, 5th Baron of Foulis received a charter from the Earl of Sutherland during the reign of Alexander II of Scotland, but this charter cannot be traced.[11] However, George Martine of Clermont (1635–1712) reported[12] that the founder was a brother of Áine Ni Catháin, known to have married Aonghus Óg Mac Domhnaill of Islay about 1300, both being children of Cú Maighe na nGall Ó Catháin. Áine is said to have been accompanied, as part of her tocher (dowry), by many men of different surnames. The genealogist and lexicographer David Kelley argues that if a brother of Àine, this places "Donald" in the late 13th century. Kelley also speculates that the "Donald le fiz Kan" granted £10 per annum by the Treasury of Scotland in 1305,[13] is the same man, with a Norman-Scots rendition of Domnall O'Cathain.

DNA studies show that about a fifth of contemporary Munro men tested have a common patrilineal ancestor of Y chromosome Haplogroup I2a-P37.2, but this minority includes documented descendants of two sons of Hugh Munro of Foulis, "9th baron": George Munro 10th baron, and John Munro of Milntown.[14] Hence Hugh, who died in 1425, must also have borne this Y chromosome. While these findings do not exclude a much earlier founder, the degree of subsequent variation in male Munros of this haplogroup suggests a common ancestor in about the 14th century. DNA studies also indicate shared patrilineal ancestry in the first millennium with several families whose documented ancestry is from South West Ireland, most notably the Driscolls of Cork,[14] consistent with the Munro tradition of Irish origins.

Wars of Scottish Independence

By tradition, during the Wars of Scottish Independence, chief Robert Munro, 6th Baron of Foulis led the clan in support of Robert the Bruce at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314.[15] Robert Munro survived the battle but his son, George, was killed. George however had already had a son of his own, also called George, who succeeded his grandfather Robert as chief and led the clan at the Battle of Halidon Hill in 1333 where he died.[15]

Recorded origins

The clan name Munro, which in Gaelic is Rothach, Roich, or Mac an Rothaich, means Ro - Man or Man from Ro, and supports the traditional origin of the clan in the River Roe area in Ireland. However this tradition only exists in writing from the late 17th century.[16] The first chief of Clan Munro documented by contemporary evidence is Robert de Munro (traditionally the 8th Baron) who died in 1369.[17] He was married to a relative of the Earl of Ross and had many charters confirmed to him under David II of Scotland including one in 1350 for the "Tower of Strathskehech" and "Estirfowlys".[18] The "de" particle was Norman for "of", and thus suggests some Norman influence. The Normans introduced the feudal system to Scotland and the Clan Munro Association states that the Munros made the transition from Celtic chiefs to feudal lords, but it is not clear when this occurred.[19] Robert de Munro was killed in an obscure skirmish fighting in defence of Uilleam III, Earl of Ross in 1369.[15] His son, Hugh Munro, was also granted many charters including one in respect of the "Tower of Strathschech" and "Wesstir Fowlys" by Euphemia I, Countess of Ross in 1394.[15]

It is a common misconception that every person who bears a clan's name is a lineal descendant of the chiefs.[20] Many clansmen although not related to the chief took the chief's surname or a variant of it as their own to show solidarity, for basic protection or for much needed sustenance.[20][21]

15th century and clan conflicts

In 1411 a major feud broke out between Robert Stewart, Duke of Albany and Domhnall of Islay, Lord of the Isles over the Earldom of Ross. This resulted in the Battle of Harlaw where chief Hugh Munro, 9th Baron of Foulis rose up in support of the Lord of the Isles.[23] The Munros are said to have fought in the Lord of the Isles 'host' against an army of Scottish Lowlanders led by Alexander Stewart, Earl of Mar.[24] In 1428 a group of Munros were granted remission by King James I of Scotland for past offences when he came to Inverness to assert his authority in the Highlands.[25]

In 1452, there was a rebellion by a force of tribes loyal to Mackenzie of Kintail who had taken as hostage the Earl of Ross's nephew. This resulted in the Battle of Bealach nam Broig, fought north-west of Ben Wyvis, where the Munros and Dingwalls rescued the Ross hostage and exterminated their enemies but with a great loss of their own men.[26] Two years later in 1454 John Munro, 1st of Milntown, uncle of the next chief, led the Clan Munro on a raid into Perthshire; on their return, they were ambushed by the Clan Mackintosh which resulted in the Battle of Clachnaharry.[27]

In 1495, King James of Scotland assembled an army at Glasgow and many of the Highland chiefs made their submissions to him, including the Munro and Mackenzie chiefs. In 1497, MacDonald of Lochalsh rebelled against the king, invading the lands of Ross-shire where, according to early 19th-century historian Donald Gregory, he was defeated at the Battle of Drumchatt (1497) by the Munros and Mackenzies.[28] However late 19th-century historian Alexander Mackenzie disputes the Munros' presence at the battle of 1497, quoting 17th-century historian Sir Robert Gordon whose account does not include the Munros.[29] Alexander Mackenzie states that the Munros and Mackenzies actually fought each other at Drumchatt in 1501.[30]

In 1500, the Munros of Milntown began construction of Milntown Castle, which was opposed by the Rosses as being too close to their Balnagown Castle.[31]

16th century and clan conflicts

.jpg.webp)

In the early 16th century a rebellion broke out by Domhnall Dubh, chief of Clan MacDonald, against the king. The MacDonalds were no longer Lords of the Isles or Earls of Ross. Cameron of Lochiel supported the rebel Domhnall Dubh. In 1502, a commission was given to the Earl of Huntly, the Lord Lovat, and William Munro of Foulis to proceed to Lochaber against the rebels.[32] There in 1505 William Munro of Foulis, whilst on "the King's business" was killed by Cameron of Lochiel.[33] It is Clan Cameron tradition that they defeated a joint force of Munros and Mackays at the Battle of Achnashellach in 1505.[34] Domhnall Dubh was captured in 1506 and Ewen Cameron was later executed.[35]

On 30 April 1527, a bond of friendship was signed at Inverness between: Chief Hector Munro of Foulis; John Campbell of Cawdor, the Knight of Calder; Hector Mackintosh of Mackintosh, Chief of Clan Mackintosh, captain of Clanchattan; Hugh Rose of Kilravock, Chief of Clan Rose; and "Donald Ilis of Sleat".[36] In 1529 a charter was signed between chief Hector Munro, 13th Baron of Foulis and Lord Fraser of Lovat to assist and defend each other.[37]

In 1544 Robert Munro, 14th Baron of Foulis signed a bond of kindness and alliance with the chief of Clan Ross of Balnagowan.[38] The Foulis Writs hint that in 1534 James V of Scotland was aware of the Munros as a fighting force.[33] A little later in 1547, Robert Munro, 14th Baron of Foulis "with his friends and followers having gone to resist the English who invaded Scotland", was killed at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh.[33] In 1549, Donald Monro, Dean of the Isles, visited Finlaggan Castle, seat of the chiefs of Clan Donald.[39][40]

Robert Mor Munro, 15th Baron of Foulis was a staunch supporter and faithful friend of Mary, Queen of Scots, and consequently was treated favourably by her son James VI of Scotland. When Mary went to Inverness Castle in 1562 the gates of the castle were shut against her. The Frasers and Munros, esteemed the "bravest" clans in the north took the castle for the Queen in the Siege of Inverness (1562).[41]

Between 1569 and 1573 Andrew Munro, 5th of Milntown defended and held, for three years, the Castle Chanonry of Ross, which he had received from the Regent Moray who died in 1569, against the Clan MacKenzie, at the expense of many lives on both sides. The feud was settled when the castle was handed over to the Mackenzies by an "act of pacification".[42][43] In 1587, Foulis Castle's "tower and fortalice" are mentioned in a charter from the Crown.[44] In 1597, the Battle of Logiebride took place between clansmen from the Clan Munro and the Bain of Tulloch family against clansmen from the Clan Mackenzie and the MacLeods of Raasay.[45]

17th century

Thirty Years' War

During the early 17th century the Munros continued their strong military traditions, fighting in the continental Thirty Years' War where Robert Munro, 18th Baron of Foulis, known as the Black Baron, and 700 members of Clan Munro, along with many men from the Clan Mackay, joined the army of Gustavus Adolphus, in defence of Protestantism in Scandinavia. Robert died of an infected wound in Ulm in 1633.[46] General Robert Monro of the Obsdale branch, and cousin of the Black Baron, played a more prominent role. Robert's men served with distinction and received the name of the "Invincibles" in recognition of their prowess. His account of his experience during the Thirty Years' War was published as Monro, His Expedition With the Worthy Scots Regiment Called Mac-Keys.[46] There were 27 field officers and 11 captains of the name of Munro in the Swedish army.[47]

Bishops' Wars and Civil War

During the Bishops' Wars General Robert Monro of the Obsdale branch of the clan laid siege to and took Spynie Palace, Drum Castle and Huntly Castle. From 1642 to 1648 he commanded the Scottish Covenanter army in Ireland during the Irish Confederate Wars.[48][49] There were several Munro officers in regiments that fought on the Covenanter side at the Battle of Philiphaugh in 1645.[50]

Sir George Munro, 1st of Newmore who fought in Ireland as a Covenanter later became a royalist after his uncle Robert Monro was imprisoned by Cromwell in 1648. In September 1648, George Munro's Engager Covenanter forces (who favoured the royalists) defeated Archibald Campbell, 1st Marquess of Argyll's Kirk Party Covenanter forces at the Battle of Stirling.[51][52] In 1649, Colonel John Munro of Lemlair, as a royalist, took part in the Siege of Inverness (1649).[53] On hearing of this rising, James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose, leader of royalist forces and his invading army of foreigners landed in Ross-shire, hoping for support from the clans. However, he was opposed by the Munros, Rosses and Sutherlands who then chose to support the Scottish Argyll Covenanter Government. The Munros, led by John Munro of Lemlair, together with their allies, comprehensively defeated the invading army at the Battle of Carbisdale in 1650.[54][55] Historian Charles Ian Fraser states that the clan had no cause to be hesitant about their part in this action and that some historians, such as John Buchan have done less than justice to it.[56] By 1651 the Scottish Covenantor Government had become disillusioned with the English parliament and supported the royalists instead. William Munroe was one of four Munroes captured at the Battle of Worcester and transported to America.[57] The Restoration of Charles II took place in 1660. The then chief's brother, George Munro, 1st of Newmore commanded the king's forces in Scotland from 1674 to 1677.[58]

In 1689, chief Sir John Munro, 4th Baronet was one of the Scottish representatives who approved the formal offer of the Scottish Crown to William of Orange and his Queen.[59] In the same year George Munro, 1st of Auchinbowie, commanded royalist forces that defeated the Jacobites at the Battle of Dunkeld.[59][60]

18th century

After Queen Elizabeth I of England died without an heir, King James VI of Scotland also became King of England in the Union of the Crowns in 1603. Just over a century later in 1707 the parliaments of England and Scotland were also united in the Acts of Union 1707 to form the Kingdom of Great Britain.

Jacobite rising of 1715

In what is known as the Skirmish of Alness, during the Jacobite Rising of 1715, William Mackenzie, 5th Earl of Seaforth led a force of 3000 men in support of the Jacobites, where they forced the retreat of a smaller force that was loyal to the British Government which was commanded by the Earl of Sutherland and included the Munros led by Sir Robert Munro, 6th Baronet of Foulis, as well as the Mackays and Rosses who were led by Lord Reay.[61] Much of the Ross's lands were ravaged and the Munros returned to find their lands plundered.[61][62][63] This was fully retaliated by the Munros who then raided the Mackenzie lands in the Siege of Brahan.[64][63]

The Siege of Inverness (1715) was brought to an end when the Mackenzie Jacobite garrison surrendered to Fraser of Lovat on the same day that the Battle of Sheriffmuir was fought and another Jacobite force was defeated at the Battle of Preston. Colonel Sir Robert Munro, 6th Baronet of Foulis then marched into the town of Inverness with 400 Munros and took over control as governor from Fraser. Government troops soon arrived in Inverness and for some months the process of disarming the rebels went on, assisted by a Munro detachment under George Munro, 1st of Culcairn.[40]

The clan rivalries which had erupted in rebellion were finding an outlet in local politics. Mackenzie's Earl of Seaforth title came to an end in 1716, and it was arranged that while Clan Ross held the county parliamentary seat the Munros would represent the Tain Burghs. Ross ascendancy was secure in Tain, and from 1716 to 1745 the Munros controlled the county town of Dingwall, with one of Robert Munro's brothers as provost, although there were two armed Munro "invasions" of the town in 1721 and 1740, when opposing councillors were abducted to secure a favourable result (for the first incident Colonel Robert and his brother were fined £200 each, and after the second his parliamentary career came to an abrupt end with defeat at the 1741 election). Sir Robert Munro, 5th Baronet's younger son, George Munro, 1st of Culcairn raised an Independent Highland Company from his father's clan to fight at the Battle of Glen Shiel in 1719 where they defeated the Jacobites.[63][65]

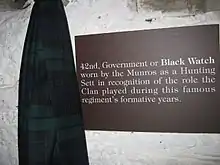

Black Watch and war against France

General Wade's report on the Highlands in 1724 estimated the combined clan strength of the Munros and Rosses at 700 men.[66] In 1725, six Independent Highland Companies were formed: one of Munros, one of Frasers, one of Grants and three of Campbells. These companies were known by the name Am Freiceadan Dubh, or the Black Watch. By 1740 it had become the 43rd Highland regiment and was later renumbered the 42nd. Sir Robert Munro was appointed lieutenant-colonel. Among the captains were his next brother, George Munro, 1st of Culcairn, and John Munro, 4th of Newmore, promoted lieutenant-colonel in 1745. The surgeon of the regiment was Robert's younger brother, Dr Duncan Munro.[40]

Their first action came on 11 May 1745, at the Battle of Fontenoy. Allowed "their own way of fighting", each time they received the French fire Col. Sir Robert Munro ordered his men to "clap to the ground" while he himself, because of his corpulence, stood alone with the colours behind him. For the first time in a European battle, they introduced a system of infantry tactics (alternately firing and taking cover) that has not been superseded. Springing up and closing with the enemy, they several times drove them back, and finished with a successful rearguard action against the French cavalry.[40][67][68]

Jacobite rising of 1745

In June, 1745, a month after the Battle of Fontenoy, Sir Robert Munro, 6th Baronet was "rewarded" by an appointment to succeed General Ponsonby as Colonel of the English 37th Regiment of Foot.[68] When the Jacobite rising of 1745 broke out, Robert's friends in the Highlands hoped for his presence among them. One wrote that it would have been "the greatest service to His Majesty and the common cause", but it was not to be. The Munros supported the British Government during the Jacobite risings.

Sir Robert Munro, 6th Baronet had been fighting at the second Battle of Falkirk (1746) when, according to the account of the rebels, the English 37th Regiment that he was commanding ran away and he was surrounded and attacked by seven Cameron Jacobites; he killed at least two with his half-pike before being shot by a Jacobite commander with a pistol.[68] The Jacobites wished to do special honour to their opponent: they (the Macdonalds),[68] buried Robert in the grave of Sir John de Graham who died at the first Battle of Falkirk (1298). The graves can be seen in Falkirk churchyard.[40][68]

Robert's son, Sir Harry Munro, 7th Baronet, who served as an officer in Loudon's Highlanders, had been captured at the Battle of Prestonpans in September, 1745. He returned home to find Foulis Castle had been partially destroyed by Jacobites after the Battle of Falkirk. A few months after Falkirk the Jacobites were finally defeated at the Battle of Culloden by government forces. After the rising was suppressed, a Munro Independent Company under Harry continued to police the Highlands but was disbanded in 1748. Harry set about rebuilding the castle as it is today, incorporating what he could of the original building which now appears as a mansion house built in a formal Georgian style rather than the defensive fort it once was.[65]

In 1754, Lieutenant Hector Munro, 8th of Novar was ordered to Badenoch to apprehend certain rebels in that district, with special instructions to apprehend John Dubh Cameron, better known as "Sergent Mor" of Clan Cameron, who he successfully captured.[70]

Later clansmen

- British Empire and military

Sir Hector Munro, 8th of Novar (1726–1805), Sir Thomas Munro, 1st Baronet of Lindertis (1761 to 1827) and John Munro, 9th of Teaninich (b.1778) were Scottish Generals in the British Army who had great success in India. James Munro (VC) was a Scottish recipient of the Victoria Cross during the Crimean War.

- Mountaineering

Sir Hugh Munro, 4th Baronet (of Lindertis) (1856–1919) was a founding member of the Scottish Mountaineering Club and produced the first scientific list of all the mountains in Scotland over 3000 ft which are known as Munros.

- Science and medicine

Four direct generations, from the distinguished Auchinbowie-Bearcrofts branch of the clan: John Munro (surgeon), Alexander Monro (primus), Alexander Monro (secundus) and Alexander Monro (tertius) were professors of anatomy at Edinburgh University. From the Monro of Fyrish branch of the clan four generations occupied successively the position of (Principal) Physician of Bethlem Royal Hospital.

- Academia

John U. Monro, dean of Harvard College, was a member of the tenth generation of the Lexington, Massachusetts branch of Clan Munro.[71] His youngest brother[72] Sutton Monro co-developed the Robbins–Monro algorithm with his doctoral advisor Herbert Robbins.[73][74]

Fifth President of the United States of America

President James Monroe (April 28, 1758 – July 4, 1831) was the great-great-grandson of Patrick Andrew Monroe who emigrated from Scotland to the United States in the mid seventeenth century. At the time, the spelling of surnames was not standardized, and Monroe is simply another spelling of Munro. He is believed to have been descended from Robert Munro, 14th Baron of Foulis.[75]

Clergy

The Munros were also prominent members of the Scottish clergy in the north of Scotland. Andrew Munro (d.1454) was Archdeacon of Ross and for a short time Bishop of Ross.[76] Sir Donald Monro was Dean of the Isles and in 1549 wrote the Description of the Western Isles of Scotland.[77] John Munro of Tain (d.1630) was a Presbyterian minister.[78] Rev. Robert Munro (1645–1704) was a Catholic priest who was persecuted for his beliefs and died in imprisonment.[79]

Castles

- Foulis Castle seat of the Munros of Foulis, the chiefs of the Clan Munro.[80]

- Milntown Castle,[80] was the seat of the Munros of Milntown, the senior cadet branch of the Clan Munro.

- Newmore Castle,[80] was seat of the Munros of Newmore.

- Teaninich Castle was seat of the Munros of Teaninich.

- Balconie Castle was the seat of the Munros of Balconie.

- Novar House,[80] was seat of the Munros of Novar.

- Lemlair House was the seat of the Munros of Lemlair.

- Contullich Castle, thought to have first been built in the 11th century,[80] owned by various branches of the Clan Munro.

- Allan, near Tain, site of castle held by the Munros.[80]

- Ardross Castle originally held by the Munros but later passed to the Clan Matheson.[80]

- Loch Slin Castle, near Tain, held by the Munros in the seventeenth century but later passed to the Clan Mackenzie.[80]

- Strome Castle, on the shore of Loch Carron, Ross-shire, was held in the early 16th century by Hector Munro, I of Erribol who was Governor of the castle on behalf of the Clan MacDonell of Glengarry who were then in possession of it, and he also married the daughter of the Glengarry chief.[81]

Chiefs

The succession of a Highland Chief has traditionally followed the principle of agnatic primogeniture or patrilineal seniority, whereby succession passes to the former Chief's closest male relative. Sir Hugh Munro, 8th Baronet of Foulis died in 1848, followed 8 months later by the death of his daughter Mary Seymour Munro and although he had a natural son named George, he was succeeded in the Foulis estates and also the Baronetcy of Foulis by the male representative of the Munro of Culrain cadet branch, Sir Charles Munro, 9th Baronet. The 11th Baronet Foulis was succeeded by his eldest daughter Eva Marion Munro as chief of the clan, two sons having predeceased him. Eva Marion Munro married Col C. H. Gascoigne, and their son Patrick took the surname 'Munro' of his maternal grandfather to become clan chief.[82] However, the Nova Scotian Baronetcy of Foulis (1634) could only pass to a direct male descendant of the Baronets and was succeeded to by a cousin of the 11th Bart. Sir George Hamilton Munro, 12th Baronet (1864–1945). In 1954, Sir Arthur Herman Munro, 14th baronet, registered the Arms and Designation of Foulis-Obsdale to distinguish them from those of Munro of Foulis.[83] The current Baronet Munro of Foulis is listed as Dormant: Exant under research by the Standing Council of Baronets at www.barotonage.org . See Main Article: Munro Baronets.

Tartans

| Tartan image | Notes |

|---|---|

| Munro Ancient tartan |

.png.webp) | Monrois tartan as printed in Vestiarium Scoticum in 1842 |

See also

- Munro Baronets

- Munro (disambiguation)

- Munroe (disambiguation)

- Monro (disambiguation)

- Monroe (disambiguation)

- Black Watch Military regiment originally formed from highland clans including Clan Munro.

- Munro Mountains in Scotland with height over 3000 ft.

References

- 1 2 Mac an Tàilleir, Iain. "Ainmean Pearsanta" (docx). Sabhal Mòr Ostaig. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Clan Munro Profile scotclans.com. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Scots Kith & Kin. HarperCollins. 2014. p. 81. ISBN 9780007551798.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 Mackenzie, Alexander (1898), pp. ix–x.

- ↑ Kelley, David H. (1969), pp. 65–78.

- 1 2 Fraser, C. I of Reelig (1954), p. 16.

- ↑ Mackenzie, Alexander (1898), p. 6.

- ↑ Fraser, C. I of Reelig (1954), p. 5.

- ↑ Gracie, James (1997), p. 12.

- 1 2 Gracie, James (1997), p. 13.

- ↑ Fraser, C. I of Reelig (1954), p. 16; Nisbet, Alexander. (1722), p. 350

- ↑ Martine, George (1900), pp. 36–40.

- ↑ Moor, C (1905), p. 45.

- 1 2 Munro, Colin (December 2015). "The Deep Ancestry of the Munros" (PDF). Newsletter of the Clan Munro (Association) Australia. Vol. 13, no. 3. Australia: Clan Munro (Association) Australia. pp. 4–5. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 Fraser, C. I of Reelig (1954), p. 17.

- ↑ Clan Munro Information Sheets clanmunro.org.uk. Retrieved 09, February 2013

- ↑ Munro, R.W (1978), pp. 2 - 3 - on opposite unnumbered page - paragraph K.

- ↑ Fraser, C. I of Reelig (1954), pp. 16–18.

- ↑ Clan Munro magazine. No. 26. Published by the Clan Munro Association. 2012. p. 15.

- 1 2 scotlandspeople.gov.uk. "Clan-based surnames". Scotland's People. Archived from the original on 14 June 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ↑ Fraser, C. I of Reelig (1954), p. 15.

- ↑ Gracie, James (1997), pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Munro, James Phinney (1900), p. 14.

- ↑ Fraser, C. I of Reelig (1954), p. 19. Quoting: MacDonald, Hugh. (1914), p. 30

- ↑ Fraser, C. I of Reelig (1954), p. 19

- ↑ Gordon, Sir Robert (1580–1656), p. 36.

- ↑ Gordon, Sir Robert (1580–1656), pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Gregory, Donald (1836), p. 92.

- ↑ Gordon, Sir Robert (1580–1656), p. 77.

- ↑ Mackenzie, Alexander (1898), pp. 28–34.

- ↑ Gordon, Sir Robert (1580–1656), p. 146.

- ↑ Gregory, Donald (1836), p. 97.

- 1 2 3 Fraser, C. I of Reelig (1954), p. 21.

- ↑ Battle of Achnashellach clan-cameron.org. Retrieved 09, February 2013.

- ↑ Stewart, John (1974).

- ↑ Innes, Cosmo and Campbell, John (1859), pp. 167–168.

- ↑ Mackenzie, Alexander (1898), p. 36.

- ↑ The Scottish Clans and Their Tartans. p. 79. Library Edition. Published by W. & A. K. Johnston, Limited. Edinburgh and London. 1885.

- ↑ Why Finlaggan ? Archived 6 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine finlaggan.com. Retrieved 09, February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Anderson, William (1836), pp. 213–218.

- ↑ Buchanan, George (1579), p. 461.

- ↑ Gordon, Sir Robert (1580–1656), p. 155.

- ↑ Keltie, John (1885), p. 92; Gordon, Sir Robert (1580–1656), p. 154

- ↑ Munro, R.W (1978), p. iii.

- ↑ Gordon, Sir Robert (1580–1656), p. 236.

- 1 2 Monro, Robert (1637).

- ↑ Mackay, John (1885); Monro, Robert (1637)

- ↑ Mackay, John (1885).

- ↑ Buchan, John (1928), p. 354.

- ↑ Munro, R.W (1978), p. 12 - on opposite unnumbered page - paragraph M/56.

- ↑ "Battle of Stirling@ScotsWars.com". Archived from the original on 14 April 2005.

- ↑ Henderson, Thomas Finlayson (1894). Quoting: Rushworth, John (17th century), p. 1276

- ↑ Roberts, John L (2000), p. 106.

- ↑ Roberts, John L (2000), p. 110.

- ↑ Battle of Carbisdale Archived 27 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine scotwars.com. Retrieved 09, February 2013.

- ↑ Fraser, C. I of Reelig (1954), p. 26; Buchan, John (1928), p. 354

- ↑ Munro, Richard, S.

- ↑ Way, George of Plean and Squire, Romilly of Rubislaw (1994), p. 283.

- 1 2 Fraser, C. I of Reelig (1954), p. 26.

- ↑ Inglis, John (1911), pp. 40–44.

- 1 2 Sage, Donald (1789), pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Rose, D. Murray (1897), p. 73.

- 1 2 3 Fraser, C. I of Reelig (1954), p. 27.

- ↑ Fraser, James of Castle Leathers (1696–1737), pp. 78–80.

- 1 2 Clan Munro Magazine No. 14 by R. W. Munro

- ↑ Johnston, Thomas Brumby (1899), p. 26.

- ↑ Fraser, C. I of Reelig (1954), p. 28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McNie, Alan (1986), pp. 24–26.

- ↑ "Return of Loudoun's Regiment and 2 Independent Companies, quartered in the Highlands". Ref: SP 54/34/4E, The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Greater London.

- ↑ Mackenzie, Alexander (1898), pp. 515–536.

- ↑ Capossela, Toni-Lee (17 December 2012). John U. Monro: Uncommon Educator. Louisiana State University Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 9780807145562.

- ↑ "Sutton Monro, former engineering professor at Lehigh University". The Morning Call. 7 March 1995. Archived from the original on 6 November 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ↑ Robbins, Herbert; Monro, Sutton (1951). "A Stochastic Approximation Method". The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 22 (3): 400–407. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177729586. ISSN 0003-4851. JSTOR 2236626.

- ↑ Groover, Mikell (2010). History of the Department of Industrial and Systems Engineering at Lehigh University,1924–2010 (PDF) (Report). p. 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ↑ Monroe, Horace, Canon of Southwark (1929). Foulis Castle and the Monroes of Lower Iveagh. London: Mitchell Hughes and Clarke.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Dowden, John (1912), p. 218.

- ↑ Ross, Alexander (1884), pp. 142–144.

- ↑ Mackenzie, Alexander (1898), p. 410 - 413.

- ↑ McHardy, Stuart (2006), pp. 134–138.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Coventry, Martin (2008), p. 441.

- ↑ Mackenzie, Alexander (1898), p. 350.

- ↑ "The Chief".

- ↑ Adam, F. (1970). The Clans, Septs & Regiments of the Scottish Highlands (8th ed.). Clearfield.

Bibliography

- Anderson, William (1836). The Scottish Nation: Or the families, surnames families, honours and Geographical History of the People of Scotland. Vol. III. Edinburgh: A Fullerton & Co.

- Buchan, John (1928). Montrose: A History. Edinburgh: Nelson.

- Buchanan, George; Aikman, James (1827) [Printed from original manuscript from 1579]. The History of Scotland. Glasgow and Edinburgh: Blackie, and Archibald Fullerton & Co.

- Coventry, Martin (2008). Castles of the Clans: The Strongholds and Seats of 750 Scottish Families and Clans. Musselburgh Scotland: Goblinshead. ISBN 978-1-899874-36-1.

- Dowden, John (1912). The Bishops of Scotland. Glasgow: J. Maitland Thomson.

- Fraser, C.I of Reelig (1954). The Clan Munro. Stirling: Johnston & Bacon. ISBN 0-7179-4535-9.

- Fraser, James of Castle Leathers (1889) [Printed from original manuscript of 1696 - 1737]. Major Fraser's manuscript; his adventure in Scotland and England; his mission to, and travels in France in search of his chief; his services in the Rebellion, and his quarrels with Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat, 1696-1737. Edinburgh: D. Douglas.

- Gordon, Sir Robert (1813) [Printed from original manuscript 1580 - 1656]. A Genealogical History of the Earldom of Sutherland. Edinburgh: A. Constable.

- Gracie, James (1997). the Munros. Lang Syne Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85217-080-6.

- Gregory, Donald (1836). History of the Western Highlands and Isles of Scotland from A.D. 1493 to A.D. 1625. Edinburgh: W. Tait. ISBN 9780859760089.

- Henderson, Thomas, Finlayson (1894). Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 38.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Inglis, John, Alexander (1911). The Monros of Auchinbowie and Cognate Families. Edinburgh: T. & A. Constable.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Innes, Cosmo; Campbell, John Frederick Vaughan of Cawdor (1859). The Book of the Thanes of Cawdor: A Series of Papers Selected from the Charter Room at Cawdor. Edinburgh.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Johnston, Thomas Brumby; Robertson, James Alexander; Dickson, William Kirk (1899). "General Wade's Report". Historical Geography of the Clans of Scotland. Edinburgh and London: W. & A.K. Johnston.

- Kelley, D.H (1969). The Claimed Irish Origin of Clan Munro. Vol. 45. The American Genealogist.

- Keltie, John, S (1885). A history of the Scottish Highlands Highland clans and Highland regiments. Edinburgh: T. C. Jack.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mackay, John (1885). An Old Scots Brigade. Edinburgh.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - MacDonald, Hugh (1914). Highland Papers. Edinburgh: Printed by T and A Constable for the Scottish History Society.

- Mackenzie, Alexander (1898). History of the Munros of Fowlis. Inverness: Scottish Highlander Office.

- Martine, George (1900). Clark, J.T (ed.). Monro (Munro) of Fowlis in Walter Macfarlane's Genealogical Collections concerning Families in Scotland. Vol. i. Edinburgh: Scottish History Society.

- McHardy, Stuart (2006). The White Cockade and other Jacobite Tales. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-84158-441-6.

- McNie, Alan (1986). Your Clan Heritage, Clan Munro. Jedburgh: Cascade Publishing Company. ISBN 0-907614-07-8.

- Monro, Robert (1637). Monro, His Expedition with the Worthy Scots Regiment. Red Cross Street, London: William Jones.

- Monroe, Horace (1929). Foulis Castle and the Monroes of Lower Iveagh. London: Mitchell, Hughes and Clarke.

- Moor, C (1905). Knights of Edward I. Vol. II (F-K). Harleian Society Visitation Series 81.

- Munroe, James Phinney (1900). A Sketch of the Clan Munro and William Munroe, Deported from Scotland, settled in Lexington, Massachusetts. Boston: George H. Ellis.

- Munro, Richard, S. History and Genealogy of the Lexington, Massachusetts, Munroes.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Munro, R.W (1978). The Munro Tree 1734. Munro. ISBN 0-9503689-1-1.

- Nisbet, Alexander (1722). System of Heraldry. vol. 1.

- Roberts, John. L. (2000). Clan, King, and Covenant: History of the Highland Clans from the Civil War to the Glencoe Massacre. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1393-5.

- Rose, D. Murray (1897). Historical notes; or, Essays on the '15 and '45. Edinburgh: W. Brown.

- Ross, Alexander (1884). The Reverend Donald Munro, M.A., High Dean of the Isles. (The Celtic Magazine, volume 9).

- Rushworth, John. Historical Collections (also known as the Rushworth Papers). From throughout 17th century. Pt. iv. vol. ii.

- Sage, Rev. Donald. A.M. Minister of Resolis (1789). Memorabilia domestica; or, Parish life in the North of Scotland. Edinburgh: J Menzies.

- Stewart, John (1974). The Camerons: A History of Clan Cameron. Clan Cameron Association.

- Way, George of Plean; Squire, Romilly of Rubislaw (1994). Collins Scottish Clan & Family Encyclopedia. HarperCollins.

- The Scottish Clans and Their Tartans (Library ed.). London and Edinburgh: Johnston & Bacon. 1885. p. 79.

External links

- www.clanmunro.org.uk - Official Website of the Clan Munro (Association) (Scotland)

- www.clanmunrousa.org - Clan Munro Association USA

- www.clanmunroassociation.ca - Clan Munro Association of Canada

- www.clanmunroassociation.org.au - Clan Munro Association Australia