S8, SB7, SM8 are disability swimming classifications used for categorizing swimmers based on their level of disability. This class includes a number of different disabilities including people with amputations and cerebral palsy. The classification is governed by the International Paralympic Committee, and competes at the Paralympic Games.

Definition

This classification is for swimming.[1] In the classification title, S represents Freestyle, Backstroke and Butterfly strokes. SB means breaststroke. SM means individual medley.[1][2] The number following indicates degree of disability, with one being the most severely physically impaired to ten having the least amount of physical disability.[3] According to the International Paralympic Committee, examples of those eligible for the S8, SB8 and SM8 classes include "Swimmers who have lost either both hands or one arm [...] also, athletes with severe restrictions in the joints of the lower limbs."[2] Jane Buckley, writing for the Sporting Wheelies, an Australian disability association, describes the swimmers in this classification as having: "full use of their arms and trunk with some leg function; Swimmers with coordination problems mainly in the lower limbs; Both legs amputated just above or just below the knee; Single above elbow amputation."[1]

Disability types

This class includes people with several disability types include cerebral palsy and amputations.[4][5][6]

Amputee

ISOD amputee A2, A3, A6, A8 and A9 swimmers may be found in this class.[6] Prior to the 1990s, the A2, A3, A6, A8 and A9 classes were often grouped with other amputee classes in swimming competitions, including the Paralympic Games.[7]

Visualization of an A6 classified swimmer competing in S8

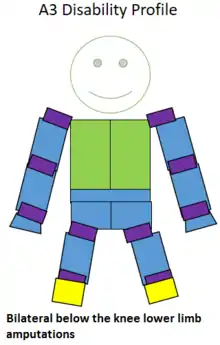

Visualization of an A6 classified swimmer competing in S8 Visualization of an A3 classified swimmer competing in S8

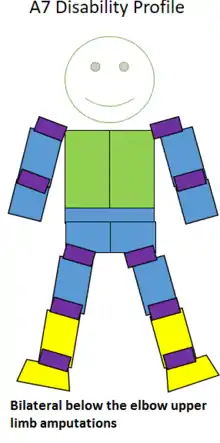

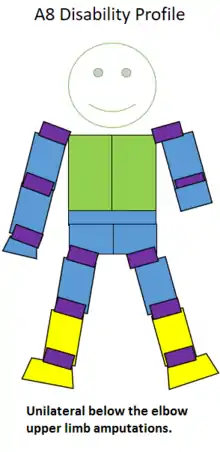

Visualization of an A3 classified swimmer competing in S8 Visualization of an A8 classified swimmer competing in S8

Visualization of an A8 classified swimmer competing in S8 Visualization of an A2 classified swimmer competing in S8

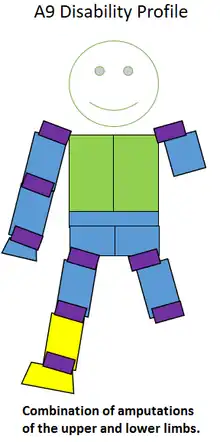

Visualization of an A2 classified swimmer competing in S8 Visualization of an A9 classified swimmer competing in S8

Visualization of an A9 classified swimmer competing in S8

Upper limb amputees

S8 and S9 amputee swimmers in this class have similar start times to people with legs amputations in S8 to S10 classes.[8] S8 amputee swimmers in this class have much shorter points of entry into the water off the block.[8] Compared to able bodied swimmers, amputee swimmers in this class have a shorter stroke length and increased stroke rate.[8] Because their legs are their greatest strength, they modify their entry into the water to take advantage of this.[8]

The nature of a person's amputations in this class can effect their physiology and sports performance. Because they are missing a limb, amputees are more prone to overuse injuries in their remaining limbs. Common problems for intact upper limbs for people in this class include rotator cuffs tearing, shoulder impingement, epicondylitis and peripheral nerve entrapment.[9]

Lower limb amputees

A3 swimmers in this class have a similar stroke length and stroke rate comparable to able bodied swimmers.[8] A study of was done comparing the performance of swimming competitors at the 1984 Summer Paralympics. It found there was no significant difference in performance in times between men and women in A2 and A3 in the 50 meter breaststroke, men and women in A2 and A3 in the 50 meter freestyle, men and women in A2, A3 and A4 in the 25 meter butterfly, and men in A2 and A3 in the 50 meter backstroke.[7]

The nature of an A2 and A3 swimmers's amputations in this class can effect their physiology and sports performance.[9][10][11] Because of the potential for balance issues related to having an amputation, during weight training, amputees are encouraged to use a spotter when lifting more than 15 pounds (6.8 kg).[10] Lower limb amputations effect a person's energy cost for being mobile. To keep their oxygen consumption rate similar to people without lower limb amputations, they need to walk slower.[9] A3 swimmers use around 41% more oxygen to walk or run the same distance as someone without a lower limb amputation.[9] A2 swimmers use around 87% more oxygen to walk or run the same distance as someone without a lower limb amputation.[9]

Upper and lower limb amputations

ISOD amputee A9 swimmers may be found in several classes. These include S2, S3, S4, S5 and S8.[12][13] Prior to the 1990s, the A9 class was often grouped with other amputee classes in swimming competitions, including the Paralympic Games.[7] Swimmers in this class have a similar stroke length and stroke rate to able bodied swimmers.[8]

The nature of a person's amputations in this class can effect their physiology and sports performance.[9][10] Because of the potential for balance issues related to having an amputation, during weight training, amputees are encouraged to use a spotter when lifting more than 15 pounds (6.8 kg).[10] Lower limb amputations effect a person's energy cost for being mobile. To keep their oxygen consumption rate similar to people without lower limb amputations, they need to walk slower.[9] Because they are missing a limb, amputees are more prone to overuse injuries in their remaining limbs. Common problems with intact upper limbs for people in this class include rotator cuffs tearing, shoulder impingement, epicondylitis and peripheral nerve entrapment.[9]

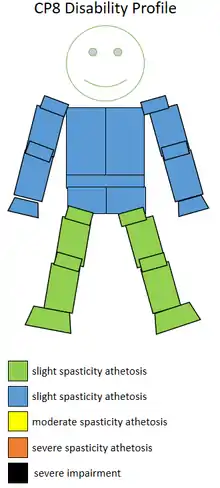

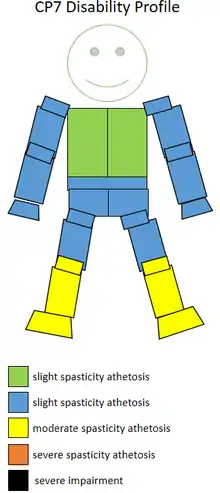

Cerebral palsy

This class includes people with several disability types include cerebral palsy. CP7 and CP8 class swimmers are sometimes found in this class.[4][5] CP7 sportspeople are able to walk, but appear to do so while having a limp as one side of their body is more effected than the other.[14][15][16][17] They may have involuntary muscles spasms on one side of their body.[16][17] They have fine motor control on their dominant side of the body, which can present as asymmetry when they are in motion.[16][18] People in this class tend to have energy expenditure similar to people without cerebral palsy.[19]

Because of the neuromuscular nature of their disability, CP7 and CP8 swimmers have slower start times than other people in their classes.[4] They are also more likely to interlock their hands when underwater in some strokes to prevent hand drift, which increases drag while swimming.[4] For S8 classified swimmers with CP, they are able to record long distances underwater. The longest distances Paralympic S8 swimmers can measure are often half that of comparable Olympic counters. This is attributed to neuromuscular related drag issues. CP swimmers are more efficient at above water swimming than underwater swimming.[4] CP8 swimmers experience swimmers shoulder, a swimming related injury, at rates similar to their able-bodied counterparts.[4] When fatigued, asymmetry in their stroke becomes a problem for swimmers in this class.[4] The integrated classification system used for swimming, where swimmers with CP compete against those with other disabilities, is subject to criticisms has been that the nature of CP is that greater exertion leads to decreased dexterity and fine motor movements. This puts competitors with CP at a disadvantage when competing against people with amputations who do not lose coordination as a result of exertion.[20]

CP7 swimmers tend to have a passive normalized drag in the range of 0.6 to 0.8. This puts them into the passive drag band of PDB6, PDB8, and PDB9.[21] CP8 swimmers tend to have a passive normalized drag in the range of 0.4 to 0.9. This puts them into the passive drag band of PDB6, PDB8, and PDB10.[22]

Spinal cord injuries

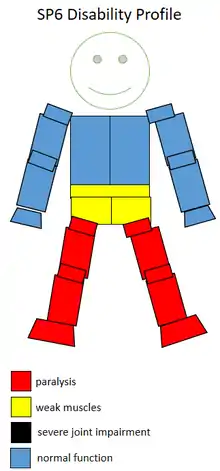

People with spinal cord injuries compete in this class, including F6 and F8 sportspeople.[23][24][25]

F6

This is wheelchair sport classification that corresponds to the neurological level L2 - L5.[26][27] Historically, this class has been known as Lower 4, Upper 5.[26][27] People with lesions at L4 have issues with their lower back muscles, hip flexors and their quadriceps.[24] People with lesions at the L4 to S2 who are complete paraplegics may have motor function issues in their gluts and hamstrings. Their quadriceps are likely to be unaffected. They may be absent sensation below the knees and in the groin area.[28]

People in this class have good sitting balance.[29] People with lesions at L4 have trunk stability, can lift a leg and can flex their hips. They can walk independently with the use of longer leg braces. They may use a wheelchair for the sake of convenience. Recommended sports include many standing related sports.[24] People in this class have a total respiratory capacity of 88% compared to people without a disability.[30]

S8 swimmers with spinal cord injuries tend to be complete paraplegics with lesions below L4 to L5. When swimming, they are able to kick but limited use of their ankles means that their propulsion from kicking can be limited. They normally do diving starts from the platform but are not able to get full power because of limited use of their legs. They do leg turns but have limited propulsion power off the wall.[31]

A study of was done comparing the performance of athletics competitors at the 1984 Summer Paralympics. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100m breaststroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100m backstroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100m freestyle. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 14 x 50 m individual medley. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100m backstroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 4 (SP5, SP6), 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100m breaststroke. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 2 (SP4), 3 (SP4, SP5) and 4 (SP5, SP6) in the 25 m butterfly. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 2 (SP4), 3 (SP4, SP5) and 4 (SP5, SP6) in the 25 m butterfly. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between women in 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 50 m butterfly. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 4 x 50 m individual medley. It found there was little significant difference in performance times between men in 5 (SP6, SP7) and 6 (SP7) in the 100 m freestyle.[7]

F8

F8 is standing wheelchair sport class.[26][32] The level of spinal cord injury for this class involves people who have incomplete lesions at a slightly higher level. This means they can sometimes bear weight on their legs.[33] In 2002, USA Track & Field defined this class as, "These are standing athletes with dynamic standing balance. Able to recover in standing when balance is challenged. Not more than 70 points in legs."[34] In 2003, Disabled Sports USA defined this class as, "In a sitting class but not more than 70 points in the lower limbs. Are unable to recover balance in challenged standing position."[26] In Australia, this class means combined lower plus upper limb functional problems. "Minimal disability."[35] It can also mean in Australia that the athlete is "ambulant with moderately reduced function in one or both lower limbs."[35] They have a normalized drag in the range of 0.6 to 0.7.[36]

History

The classification was created by the International Paralympic Committee. In 2003 the committee approved a plan which recommended the development of a universal classification code. The code was approved in 2007, and defines the "objective of classification as developing and implementing accurate, reliable and consistent sport focused classification systems", which are known as "evidence based, sport specific classification". In November 2015, they approved the revised classification code, which "aims to further develop evidence based, sport specific classification in all sports".[37]

In 1997, Against the odds : New Zealand Paralympians said this classification was graded along a gradient, with S1 being the most disabled and S10 being the least disabled.[38]

At the Paralympic Games

For the 2016 Summer Paralympics in Rio, the International Paralympic Committee had a zero classification at the Games policy. This policy was put into place in 2014, with the goal of avoiding last minute changes in classes that would negatively impact athlete training preparations. All competitors needed to be internationally classified with their classification status confirmed prior to the Games, with exceptions to this policy being dealt with on a case-by-case basis.[39]

Competitions

For this classification, organisers of the Paralympic Games have the option of including the following events on the Paralympic programme: 50 m and 100 m Freestyle, 400 m Freestyle, 100 m Backstroke, 100 m Butterfly, 100 m Breaststroke, and 200 m Individual Medley events.[40]

Paralympic records

The table below records the fastest ever Paralympic record in this class for specific events.

| Event | Class | Time | Name | Nation | Date | Games | Ref | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 m freestyle | S8 | 26.45 | WR | Xiaofu Wang | Sep 14, 2008 | 2008 Beijing | [41] | ||

| 100 m freestyle | S8 | 58.84 | Xiaofu Wang | Sep 8, 2008 | 2008 Beijing | [42] | |||

| 400 m freestyle | S8 | 4:26.25 | WR | Sam Hynd | Sep 12, 2008 | 2008 Beijing | [43] | ||

| 100 m backstroke | S8 | 1:06.33 | WR | Konstantin Lisenkov | Sep 10, 2008 | 2008 Beijing | [44] | ||

| 100 m backstroke | S8 | 1:06.33 | WR | Konstantin Lisenkov | Sep 10, 2008 | 2008 Beijing | [44] | ||

| 100 m butterfly | S8 | 1:00.95 | WR | Peter Alan Stuart Leek | Sep 7, 2008 | 2008 Beijing | [45] | ||

| 100 m freestyle | S8 | 1:05.32 | WR | Maddison Elliott | Jul 25, 2014 | 2014 Commonwealth Games | [45] |

Records not set in finals: h – heat; r – relay 1st leg; rh – relay heat 1st leg

Records

In the S8 50 m Freestyle Long Course, the men's world record is held by China's Xiaofu Wang with a time of 00:26.45 and the women's world record is held by China's Shengnan Jiang with a time of 00:30.85.[46] In the S8 100 m Freestyle Long Course, the men's world record is held by Australia's Peter Leek and the women's world record is held by Australia's Maddison Elliott.[47]

Getting classified

Swimming classification generally has three components. The first is a bench press. The second is water test. The third is in competition observation.[48] As part of the water test, swimmers are often required to demonstrate their swimming technique for all four strokes. They usually swim a distance of 25 meters for each stroke. They are also generally required to demonstrate how they enter the water and how they turn in the pool.[49]

Classification generally has four phases. The first stage of classification is a health examination. For amputees in this class, this is often done on site at a sports training facility or competition. The second stage is observation in practice, the third stage is observation in competition and the last stage is assigning the sportsperson to a relevant class.[50] Sometimes the health examination may not be done on site for amputees in this class because the nature of the amputation could cause not physically visible alterations to the body.[51]

In Australia, to be classified in this category, athletes contact the Australian Paralympic Committee or their state swimming governing body. In the United States, classification is handled by the United States Paralympic Committee on a national level. The classification test has three components: "a bench test, a water test, observation during competition." American swimmers are assessed by four people: a medical classified, two general classified and a technical classifier.[52]

Competitors

Swimmers who have competed in this classification include Amanda Everlove,[53] Sean Fraser,[53] and Heather Frederiksen,[53] who all won medals in their class at the 2008 Paralympics.[53] World champion Robert Griswold is also in this class.

References

- 1 2 3 Buckley, Jane (2011). "Understanding Classification: A Guide to the Classification Systems used in Paralympic Sports". Archived from the original on April 11, 2011. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- 1 2 IPC Swimming Classification

- ↑ Shackell, James (2012-07-24). "Paralympic dreams: Croydon Hills teen a hotshot in pool". Maroondah Weekly. Archived from the original on 2012-12-04. Retrieved 2012-08-01.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Scott, Riewald; Scott, Rodeo (2015-06-01). Science of Swimming Faster. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736095716.

- 1 2 Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- 1 2 Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 van Eijsden-Besseling, M. D. F. (1985). "The (Non)sense of the Present-Day Classification System of Sports for the Disabled, Regarding Paralysed and Amputee Athletes". Paraplegia. International Medical Society of Paraplegia. 23. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Vanlandewijck, Yves C.; Thompson, Walter R. (2011-07-13). Handbook of Sports Medicine and Science, The Paralympic Athlete. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444348286.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Miller, Mark D.; Thompson, Stephen R. (2014-04-04). DeLee & Drez's Orthopaedic Sports Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9781455742219.

- 1 2 3 4 "Classification 101". Blaze Sports. Blaze Sports. June 2012. Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ↑ DeLisa, Joel A.; Gans, Bruce M.; Walsh, Nicholas E. (2005-01-01). Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9780781741309.

- ↑ Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ↑ "ritgerd". www.ifsport.is. Archived from the original on 2016-05-05. Retrieved 2016-07-25.

- ↑ "CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM FOR STUDENTS WITH A DISABILITY". Queensland Sport. Queensland Sport. Archived from the original on April 4, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ↑ "Classification Made Easy" (PDF). Sportability British Columbia. Sportability British Columbia. July 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Clasificaciones de Ciclismo" (PDF). Comisión Nacional de Cultura Física y Deporte (in Mexican Spanish). Mexico: Comisión Nacional de Cultura Física y Deporte. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- 1 2 "Kategorie postižení handicapovaných sportovců". Tyden (in Czech). September 12, 2008. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ↑ Cashman, Richmard; Darcy, Simon (2008-01-01). Benchmark Games. Benchmark Games. ISBN 9781876718053.

- ↑ Broad, Elizabeth (2014-02-06). Sports Nutrition for Paralympic Athletes. CRC Press. ISBN 9781466507562.

- ↑ Richter, Kenneth J.; Adams-Mushett, Carol; Ferrara, Michael S.; McCann, B. Cairbre (1992). "llntegrated Swimming Classification : A Faulted System" (PDF). Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly. 9: 5–13. doi:10.1123/apaq.9.1.5.

- ↑ Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ↑ Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ↑ International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- 1 2 3 Winnick, Joseph P. (2011-01-01). Adapted Physical Education and Sport. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736089180.

- ↑ Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 National Governing Body for Athletics of Wheelchair Sports, USA. Chapter 2: Competition Rules for Athletics. United States: Wheelchair Sports, USA. 2003.

- 1 2 Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- ↑ Goosey-Tolfrey, Vicky (2010-01-01). Wheelchair Sport: A Complete Guide for Athletes, Coaches, and Teachers. Human Kinetics. ISBN 9780736086769.

- ↑ IWAS (20 March 2011). "IWF RULES FOR COMPETITION, BOOK 4 – CLASSIFICATION RULES" (PDF).

- ↑ Woude, Luc H. V.; Hoekstra, F.; Groot, S. De; Bijker, K. E.; Dekker, R. (2010-01-01). Rehabilitation: Mobility, Exercise, and Sports : 4th International State-of-the-Art Congress. IOS Press. ISBN 9781607500803.

- ↑ International Paralympic Committee (February 2005). "SWIMMING CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION MANUAL" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee Classification Manual. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- ↑ Consejo Superior de Deportes (2011). Deportistas sin Adjectivos (PDF) (in European Spanish). Spain: Consejo Superior de Deportes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-04. Retrieved 2016-08-03.

- ↑ Foster, Mikayla; Loveridge, Kyle; Turley, Cami (2013). "S P I N A L C ORD I N JURY" (PDF). Therapeutic Recreation.

- ↑ "SPECIAL SECTION ADAPTATIONS TO USA TRACK & FIELD RULES OF COMPETITION FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES" (PDF). USA Track & Field. USA Track & Field. 2002.

- 1 2 Sydney East PSSA (2016). "Para-Athlete (AWD) entry form – NSW PSSA Track & Field". New South Wales Department of Sports. New South Wales Department of Sports. Archived from the original on 2016-09-28.

- ↑ Tim-Taek, Oh; Osborough, Conor; Burkett, Brendan; Payton, Carl (2015). "Consideration of Passive Drag in IPC Swimming Classification System" (PDF). VISTA Conference. International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved July 24, 2016.

- ↑ "History of Classification". International Paralympic Committee. Archived from the original on August 22, 2023.

- ↑ Gray, Alison (1997). Against the odds : New Zealand Paralympians. Auckland, N.Z.: Hodder Moa Beckett. p. 18. ISBN 1869585666. OCLC 154294284.

- ↑ "Rio 2016 Classification Guide" (PDF). International Paralympic Committee. International Paralympic Committee. March 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Swimming Classification". The Beijing Organizing Committee for the Games of the XXIX Olympiad. 2008. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ↑ "Beijing 2008 Paralympic Games - Men's 50m freestyle - S8: Results Final" (PDF). Beijing Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games. 2008-09-14. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- ↑ "Beijing 2008 Paralympic Games - Men's 100m freestyle - S8: Results Final" (PDF). Beijing Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games. 2008-09-08. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ↑ "Beijing 2008 Paralympic Games - Men's 400m freestyle - S8: Results Final" (PDF). Beijing Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games. 2008-09-12. Retrieved 2008-09-12.

- 1 2 "Beijing 2008 Paralympic Games - Men's 100m backstroke - S8: Results Final" (PDF). Beijing Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games. 2008-09-10. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- 1 2 "Beijing 2008 Paralympic Games - Men's 100m butterfly - S8: Results Final" (PDF). Beijing Organizing Committee for the Olympic Games. 2008-09-07. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-10. Retrieved 2008-09-11.

- ↑ "IPC Swimming World Records Long Course". International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ↑ "Maddison Elliott breaks world record at Commonwealth Games 2014 in swimming for Australia". 2014-07-25. Archived from the original on 2014-07-28. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ "CLASSIFICATION GUIDE" (PDF). Swimming Australia. Swimming Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 24, 2016.

- ↑ "Classification Profiles" (PDF). Cerebral Palsy International Sports and Recreation Association. Cerebral Palsy International Sports and Recreation Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 18, 2016. Retrieved July 22, 2016.

- ↑ Tweedy, Sean M.; Beckman, Emma M.; Connick, Mark J. (August 2014). "Paralympic Classification: Conceptual Basis, Current Methods, and Research Update". Paralympic Sports Medicine and Science. 6 (85). PMID 25134747. Retrieved July 25, 2016.

- ↑ Gilbert, Keith; Schantz, Otto J.; Schantz, Otto (2008-01-01). The Paralympic Games: Empowerment Or Side Show?. Meyer & Meyer Verlag. ISBN 9781841262659.

- ↑ "U.S. Paralympics National Classification Policies & Procedures SWIMMING". United States Paralympic Committee. 26 June 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 "Results". International Paralympic Committee. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)