Samuel Fisher | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1605/6 |

| Died | 1681 |

| Nationality | English |

| Education | University of Oxford |

| Occupation(s) | Anglican clergyman, later nonconformist teacher. |

| Years active | 1630–81 |

| Spouse | Unknown |

| Children | Samuel, Hannah, Charles. |

| Religion | Presbyterian |

| Church | Church of England, later Nonconformist. |

| Ordained | 18 December 1630 |

| Writings | An Antidote against the Fear of Death A Love Token for Mourners A Fast Sermon. |

Offices held | Rector of Upton Magna Preacher at St Alban, Wood Street Vicar of Mary's, Shrewsbury Minister of Bride's, London Rector of Mary's, Thornton-le-Moors Licensed Presbyterian preacher in Birmingham. |

| Part of a series on |

| Puritans |

|---|

|

Samuel Fisher (c.1605–buried 5 September 1681)[1] was an English Puritan clergyman and writer, who was committed to a Presbyterian polity. After serving as a rural rector in Shropshire during the period of Charles I's absolute monarchy, he worked in London and Shrewsbury during the English Civil War and under the Commonwealth and in Cheshire during the Protectorate. After the Great Ejection of 1662 he settled in Birmingham, where he worked as a nonconformist preacher. The precise course of his career is a matter of some controversy.

Identity

This article concerns a Presbyterian minister who served at Shrewsbury approximately between 1645 and 1650 and afterwards at Thornton-le-Moors in Cheshire, retiring to Birmingham after his ejection. There were several Puritan clergy named Samuel Fisher and their lives seem to have become confused in some of the sources. The namesake with whom he is most often confused was a contemporary Puritan minister of Lydd who became a Quaker. An article of considerable length is devoted to this man's life in Athenae Oxonienses,[2] a generally reliable early source. The important Victorian archivist and genealogist Joseph Foster incorporated the same birth and academic details in his Alumni Oxonienses,[3] while also featuring other men called Samuel Fisher of the same period. From these, the Dictionary of National Biography article selected details, beginning with birth at Stratford-upon-Avon in 1617, as the basis for the subject of this article. In his much more recent article in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography,[1] Stephen Wright has proposed that the early life and academic records of the two ministers have been transposed, making Northampton the Presbyterian minister's birthplace. Barbara Coulton's recent Regime and Religion, a study of Shrewsbury through the Reformation and English Civil War, states that the Shrewsbury Samuel Fisher was not the one born at Stratford,[4] suggesting that a new consensus has now emerged that allows a biographical thread to be traced. However, it is not universal: the ODNB article on the Quaker minister still gives him the same parentage and academic record as Wright proposes for the Presbyterian minister who forms the subject of this article.[5]

Early life and education

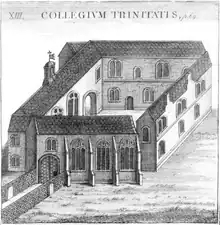

Stephen Wright identifies the Presbyterian Fisher as the son of John Fisher of Northampton, born late in 1605 or early in 1606, who matriculated at Trinity College, Oxford in 1623.[1] The argument for this takes into account the matriculation record, which gives this individual's age as 18. This squares well with a date of birth, calculated from a published sermon and will, between 8 November 1605 and 10 March 1606. Assuming Wright's argument is correct, the remainder of Fisher's academic record, sees him graduating B.A. at Trinity in 1627 and M.A. in 1630 at New Inn Hall, an institution now subsumed into Balliol College, Oxford, but then independent and a hotbed of Puritanism.

Samuel Fisher's career in maps

| Location | Dates | Nature of post | Illustration | Caption | Approximate coordinates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upton Magna | 1635–42 | Rectory in the gift of the Barker family of Haughmond Abbey |  | St Lucia's church, Upton Magna, mainly Norman with 19th century restoration. | 52°42′29″N 2°39′45″W / 52.708070°N 2.662441°W |

| Withington | 1635–42 | A chapelry of Upton Magna. |  | St John the Baptist, Withington: an entirely Victorian building on the site of the original chapel. | 52°42′46″N 2°37′40″W / 52.712803°N 2.627755°W |

| St Alban, Wood Street | 1643–6 | London church in hands of sequestrators after previous incumbent joined royalists. |  | Tower, all that is left of St Alban. Rebuilt by Wren, restored in the 19th century and destroyed in the Blitz, nothing remains of the building of Fisher's day. | 51°31′00″N 0°05′39″W / 51.516585°N 0.094087°W |

| Mary's, Shrewsbury | 1646–50 | Former Royal Peculiar, a vicarage in gift of Shrewsbury corporation. Fisher was also appointed ministerial or teaching elder in the Shropshire First Classis or Classical Presbytery. |  | Nave of St Mary's, which is largely medieval, although the exterior was greatly altered in the 18th and 19th centuries. | 52°42′31″N 2°45′05″W / 52.708733°N 2.751399°W |

| Bride's, London | 1651, 1652–4 | A vicarage taken over by its own vestry after its vicar, James Palmer, went into voluntary sequestration in 1645. |  | The church as shown in the mid-16th century Copperplate map of London. | 51°30′50″N 0°06′20″W / 51.513767°N 0.105518°W |

| Mary's, Thornton | 1654–62 | Rectory in the gift of Sir George Booth. |  | St. Mary's, Thornton-le-Moors, photographed from the churchyard. | 51°30′50″N 0°06′20″W / 51.513767°N 0.105518°W |

| Birmingham | 1662–81(?) | Nonconformist preacher, licensed as Presbyterian teacher under Royal Declaration of Indulgence, 1672. | 52°28′37″N 1°53′36″W / 52.476958°N 1.893243°W | ||

Early career

The Clergy of the Church of England database (CCEd) has a record of Samuel Fisher's ordination as priest at Eccleshall by Thomas Morton, then Bishop of Lichfield, on 18 December 1630.[6] The five years, 1630–5, between Fisher's ordination and his appointment as rector at Upton Magna, are largely unaccounted for. Rigg's account in the Dictionary of National Biography[7] implies that he worked at St Bride's Church in London before coming to Shropshire: this is almost certainly untrue, as he is known to have worked there in the 1650s.[8] Fisher's ordination by Thomas Morton seems to connect him from the outset of his career with the West Midlands and his preaching at Shrewsbury in 1633 shows that he was moderately known as a preacher in the region before his presentation to the rectory. However, it is not known how or where, or even if, he had an ecclesiastical living during this period.

Despite the mystery as to his activities in this period, Fisher did make a significant public impact on Friday 20 September 1633, when he preached a sermon in Shrewsbury. The previous week had seen a canonical visitation by Bishop Robert Wright, which had been used to enforce and to propagate High Church ideas and practices. It had provided support for Peter Studley, the very divisive curate or incumbent of St Chad's Church, Shrewsbury, who hosted the bishop as preacher in his church on 8 September, speaking on obedience to the king as a religious duty. The bishop dined with Studley, who concluded matters a week later by publicly reading out a list of injunctions on church fittings and decorations. Fisher's sermon was probably intended as a counter-blast to this Laudian triumphalism. He attacked the enforced conformity to Laudian norms, which he considered a threat to the "free passage of out blessed Gospel" and potentially a path to a restoration of popery.[9] He probably spoke in St Mary's Church, Shrewsbury, which was in the gift of the town's corporation and could provide a platform for a guest preacher: the Puritan incumbent at the time, who had probably secured the services of Fisher, was the James Betton. Another possibility is an invitation from the Puritan Julines Herring, appointed the town's public preacher at St Alkmund's Church in 1618[10] but a parishioner of St Mary's.[11]

Upton Magna

Richard Baxter remembered his old friend Fisher as being "some-time of Withington, then of Shrewsbury."[12] Wright locates him there around 1640 as a curate of Thomas Blake before a move to Upton Magna. Withington was at that time a chapelry of the parish of Upton Magna,[13] not a separate parish, and is treated as such by CCEd. In the Middle Ages Upton Magna had been dominated by Haughmond Abbey, a great Augustinian house which stood within it and held considerable property in the parish.[14] However, in the 12th century Bishop Roger de Clinton had confirmed that it was Shrewsbury Abbey that then held the tithes and advowson of both the church at Upton and its chapels, specifying Withington as one of them.[15] Some of Fisher's letters were sent from Withington at dates when he is known to have been rector of Upton Magna, but this shows no more than that he worked across the whole parish, although he may have resided at Withington.

After the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Haughmond was granted to Edward Littleton, who sold it to Sir Rowland Hill,[16] the first Protestant Lord Mayor of London. Hill's heiress at Haughmond was his sister Elizabeth, who married John Barker.[17] The resulting branch of the Barker family lived at Haughmond, using part of the monastic buildings. It seems that the Barkers acquired advowson of their local church, as a Mr Barker is named as his patron by Fisher in a letter.[18] This was John's grandson, Walter Barker of Haughmond,[4] High Sheriff of Shropshire in 1621[19] and a Parliamentarian from the beginning of the Civil War.[20] Entries in CCEd indicate that Fisher was appointed as Rector of Upton Magna on 21 July 1635. This was recorded both in William Laud's Register[21] and in the Liber cleri, recording Bishop Wright's visitation of 1639.[22] The death and burial at Withington of the previous rector, Lawrence Lee, are recorded in the register, on 1 May and 10 May 1635 respectively.[23] Bishop Wright's 1639 visitation found Thomas Blake serving as curate of Tamworth, Staffordshire,[24] a post he had held since at least 1629, a year before Fisher's ordination.[25] The word curate in this case was used to indicate a vicar, rector or other incumbent who had cure of souls, not an assistant minister, although it could be used equally well for either. The database gives no indication that Fisher ever worked as an assistant to Blake, or that Blake ever worked at Upton Magna, although such records can never be exhaustive. However, there is a record in the 1639 Liber cleri of an additional curate, Richard Drayton, in this case presumably an assistant to Fisher, at Upton Magna.[26]

As Fisher was Barker's choice, it is likely that the two men had similar views from the outset, so it is not surprising to find Fisher taking up the Puritan cause during his incumbency at Upton Magna. He seems to have followed controversies in Shrewsbury, which was very close. In a preface to some sermons he published in the 1650s, Fisher denounced those who had endangered his liberty by traducing his doctrine. While this might have applied to several phases of his career, he added in the margin: "Mr Studley and some others."[1] At the time of Fisher's appointment Studley had become mired in a controversy over his book, The Looking-glasse of Schisme in which he sought to explain a sensational murder at Clun as the result of the Puritan principles of the killer.[27] The book was published in London in 1634 and reissued in an expanded edition in 1635.[28] Under Thorough, the experiment in absolute monarchy then in force, a reasoned reply by Richard More, a layman of St Chad's parish, could not be published and it did not appear until 1641. After the furore, Studley resigned from St Chad's and moved a few miles to a living at Pontesbury. Whether his offence to Fisher was more personal than the contents of his polemic is unknown. Certainly Fisher was not one to ignore intemperate abuse of his faith. He wrote to Sir Robert Harley, then serving as MP for Herefordshire in the Long Parliament, to report some anti-Puritan banter that might have serious implications.

- 1640, December 18. Withington — The knowledge has come to my hands of some scandalous words uttered by a seminary priest. The words were these, "That those Lords who had put up the petition to his Majestye were a company of Puritan rascalls, base fellows and base scabbs." The name of the man who spoke thus is Francis Rowley. They were spoken in the house of Francis Saunders, vintner in Whitchurch. He hath been also heard to say that it is a better deed to kill one of our religion than to give a hungry man a meal's meat, who is ready to starve. This Rowley lives in Whitchurch. If this man were apprehended and the words examined by some careful Justices of the Peace I think they could be proved.

- Postscript. After writing the above I acquainted my patron Mr. Barker with Rowley's words, and his purpose is to open this business to Sir Richard Newport.[18]

With civil war looming in the summer of 1642, Fisher[1] and Barker[20] worked through local landed gentry networks to mobilise support for the Puritan and Parliamentarian causes. Much was hoped of Newport, who was closely connected by marriage and proximity: Newport's sister, Margaret, had been married to John Barker, Walter's brother from whom he had inherited the estate,[19] and his home at High Ercall Hall made him a close neighbour. Fisher did all he could to persuade Newport to side with Parliament,[29] with the help of Barker's cousin, Robert Charlton of Apley Castle.[20] However, a local royalist gentry circle around Francis Ottley pre-empted their efforts, seizing control of Shrewsbury and inviting Charles I to bring his army from Nottingham to occupy the town.[30] Charlton and Barker tried to send a large sum of money down the River Severn to the Parliamentarians at Bristol but it was intercepted by the Sheriff, John Welde, at Bridgnorth. Charlton escaped but Barker was detained.[31] Newport, after affecting indecision, gave the king £6000 in exchange for becoming Baron Newport.[32] Fisher seems to have fled the scene, perhaps to London. There is no record of a replacement being installed at Upton Magna.

London

On 23 January 1643 the House of Commons resolved "That the Profits belonging to the Parish Church of St. Albon's, Woodstreet, shall be forthwith sequestred: And that Mr. Fisher, an orthodox Divine, be appointed to preach there to the Parishioners, in the Stead and Place of Dr. Watts; and to receive the Profits thereof."[33] The House of Lords confirmed this on 3 March,[34] giving considerably more detail of the case, which increases the probability that this was the Samuel Fisher who had been driven out of Shropshire. Watts had been missing for six months, apparently took part in the Battle of Brentford on the royalist side and was rumoured to be serving as chaplain to Prince Rupert. A committee of sequestrators was empowered to seize the property and income of the church and to pay "Samuell Fisher, Master of Arts, a Godly, Learned, and Orthodox Divine, who is hereby appointed and required to preach every Lords-day, and to officiate as Parson, and to take Care for the Discharge of the Cure of the said Place in all the Duties thereof..." The new incumbent resigned in 1646, which fits well with the re-appearance of Samuel Fisher in Shropshire in August of that year.[1]

Shrewsbury

Appointment

Fisher was appointed by Shrewsbury's council to St Mary's, at the latest on 21 August 1646.[35] The date is given in Owen and Blakeway's 1805 History of Shrewsbury, which gives it also as the date on which the corporation voted Thomas Blake £5 annually as incumbent of St Alkmund's,[36] so it may represent the date of his official confirmation in office, rather than his actual starting date. Rigg thought that it was here Fisher was "curate to Thomas Blake."[7] A petition of 1596 to the corporation referred to a vacancy that then existed in the "Curatship of St. Maris,"[37] showing that the incumbent of St Mary's was generally known as the curate, as was the case at other Shrewsbury churches. Fisher was a curate alongside Blake, not to him or under him. He replaced James Betton, who had returned to Shrewsbury after it fell to Parliamentarians in February 1645 but later moved to Worthen.[38] The terms were generous: the public preacher's salary of £46 13s. 4d. and an additional £20 from lands bought with a bequest. The other important incumbent in the town centre was Thomas Paget, elected curate of St Chad's by the congregation. He was an older man who had made a considerable impression in 1641 by presenting Parliament with a book by his brother John that advocated a Presbyterian polity.

The Presbyterian project

A Presbyterian reorganisation of the English Church was now a leading priority, in line with Parliament's promises to its Scottish Covenanter allies in the Civil War. Only eight counties got as far as attempting to put such a scheme into practice and Shropshire was one of them.[39] The Shropshire scheme is outlined in a document, dated 29 April 1647, and issued over the signature of Edward Montagu, 2nd Earl of Manchester.[40] Entitled The Severall Divisions and Persons for Classicall Presbyteries in the County of Salop,[41] the scheme envisaged a division of the county or "province" into six areas, each covered by an organisational unit of the Church, termed a classis or classical presbytery.[42] Each classis was given a list of constituent parishes, followed by two lists of personnel: first a list of "Minister fit to bee" of it (corresponding in modern terminology to the teaching elders), and then a list of "Others fit to bee" of it (the ruling or lay elders). Shrewsbury was at the centre of Shropshire's First Classis. As Puritans of the period used the term "saint" either generally to refer to all Christians, or, in a more restricted sense, to Apostles or New Testament figures, the town centre churches were shorn of the honorific title. St Alkmund's became Alkmonds, St Chad's was rendered Cedds. Fisher's church, however, was treated inconsistently, being Saint Maries on first mention, but then simply Maries. Fisher was placed fourth in the list of clergy, below Betton, Paget and Blake, but above the other four ministers, who served rural parishes, including James Smith in Fisher's old home at Upton Magna. The laymen are headed by the mayor of Shrewsbury, Thomas Knight, although it is not stated whether ex officio or in his personal capacity. Other lay elders included Richard Pigot, the headmaster of Shrewsbury School, a number of powerful Shrewsbury merchants, particularly drapers, and gentry from the immediate area, including Fisher's old associate Robert Charlton of Apley. The most powerful figure in the classis, the town and the county was Humphrey Mackworth, as he was the military governor and headed the ruling parliamentary committee, as well as being a member of every other governing committee, an alderman of the town[43] and a JP. He must have been well known to Fisher, as he was a veteran of the lay opposition to Peter Studley at St Chad's, and, as the town's lawyer, had helped defend its control at St Mary's and St Chad's when threatened by Laud's intervention in its charter renewal.[44]

Controversy and flight

The Puritan coalition was soon in trouble, locally as well as nationally. In 1648 Mackworth was forced to play an active part in the Second English Civil War, precipitated by the king's conspiracy with the Scottish Engagers to regain his throne.[45] Fisher, described as "pastor of Marye's Salop", was one of 57 ministers to sign a document entitled A Testimony of the Ministers in the Province of Salop to the Truth of Jesus Christ and to the Solemn League and Covenant: as also against the Errors, Heresies and Blasphemies of these times and the Toleration of them.[46] This was a denunciation by committed Presbyterians of Independency or Congregationalism, an alternative Puritan model of church government that did away with structures above the local level. While Betton and Blake were also prominent among the signatories, Paget, Mackworth's own parish minister, did not sign. After Pride's Purge, the army coup that removed the moderate Presbyterians from the House of Commons, Mackworth backed the regicide and was an enthusiastic supporter of the Commonwealth of England.[43] Fisher and Blake remained with the Presbyterian mainstream, as the Covenant had envisaged a Presbyterian national Church with the monarch as its head. However, the Presbyterian polity in Shropshire withered rapidly, with only the fourth classis remaining as a fully functioning structure.[39] This was based on Whitchurch and Wem, although often known as the Bradford North Classis, after the hundred in which it fell, and was dominated by the stalwart Presbyterian Sir John Corbet,[47] one of the purged MPs.

At Shrewsbury open division came with Parliament's imposition in March 1650 of the Oath of Engagement: "I do declare and promise, that I will be true and faithful to the Commonwealth of England, as it is now established, without a King or House of Lords."[48] This was so clearly at odds with the Covenant that it was impossible for Fisher and Blake to subscribe. They preached against it, while Paget took to his pulpit and wrote for the opposite side.[49] Early notice of the English Council of State's determination to impose the Engagement at Shrewsbury came from the handling of Fisher's old friend and relative Sir Robert Harley, who had refused to subscribe. A staunch Parliamentarian, he wrote to Mackworth, also a relative, asking permission to retire to Shrewsbury.[50] Mackworth, however, was not free to allow him to settle, and on 8 May turned down his request.

- I have received yours of the 29th of April wherein you intimate your desire of coming to reside in tins garrison. I acquainted your servant Shilton with my resolution of adhering to the present government. I am now entrusted by the Parliament for the security of this garrison, and in pursuance of some private instructions I have received I shall desire that if you be not fully "satisfied to the subscribeinge of the engagement," that you will at present rather forbear than retain your intention of coming to reside here.

Harley was forced to spend his last years at Ludlow. Mackworth had made clear, as he was told to do, that the main consideration in handling dissent at Shrewsbury was state security. Fisher and Blake continued to preach against the engagement and their opposition was well known in London, where it was noted by Bulstrode Whitelocke.[49]

The general atmosphere of crisis was then greatly intensified by an outbreak of bubonic plague at Frankwell in June, which soon spread throughout Shrewsbury.[51] On 16 August the Council of State ordered Mackworth "to turn out of his garrison all such persons as, either in the pulpit or elsewhere, by seditious words endeavour to stir up sedition and uproar among the people."[52] A week later the Council named Blake and Fisher, ordering Mackworth to detain them and to "examine them as to their former and late offences."[53] Fisher later wrote of their "continual expectation of arrest" during this period, when he and Blake saw their pastoral work during the plague as the priority.[54] The epidemic reached its peak in September and October, only petering out in January 1651.[55] Fisher and Blake seem to have left towards the end of 1650.[35] At Myddle they stayed with the minister, Joshua Richardson, who had also refused the Engagement.[56] Myddle had been allocated to the second classis and the leading lay Puritan locally was Robert Corbet of Stanwardine.[57] The difference in political atmosphere away from the county town and fortress was so great that they were allowed to preach. Richard Gough, Robert Corbet's secretary, mentioned their visit in his famous Antiquities & Memoirs of Myddle:

- The two chiefe and ablest Ministers in Shrewsbury, viz. Mr. Thomas Blake, Minister of St. Chads, and Mr. Fisher of St. Mary's removed to Myddle and dwelt both in Mr. Gittin's house att the higher well; they preached often att Myddle. Mr. Fisher was a man of myddle stature and age, a fatt plump body, a round visage, and blacke haire.[58]

Some of the detail is not quite right, but Gough's physical description of the minister seems to be the only one extant. Later they ventured further north and stayed at West Felton with Samuel Hildersham and his wife Mary.[56] He was a Puritan writer, the son of Arthur Hildersham, and had been a leading figure in the second classis: they had the use of his substantial library for several months.

Shrewsbury faced a further crisis in 1651, when governor Mackworth had to face down a demand that he surrender the town to Charles Stuart's mainly Scottish army.[43] This contributed to delays in finding a replacement for Fisher at St Mary's. In 1652 the corporation and congregation approached Francis Tallents to take on the task.[59] He had scruples about supplanting Fisher, with whom he shared a Presbyterian orientation and a close friendship with Richard Baxter. However, Fisher magnanimously wrote to the parish through Richard Pigot, the headmaster, expressing "not his willingness alone, but his earnest desire to have Mr. Tallents settle with them."[60]

London again

Fisher preached at Bride's, London, (with the "Saint" omitted) apparently for two separate short periods, between his flight from Shrewsbury and his admission to the rectory of Thornton. The details are contained in the architect Walter Godfrey's monograph on the church, started as Wren's later building lay ruined in 1940. The advowson of the church belonged to Westminster Abbey – until the Dissolution of the Monasteries to the Abbot and Convent, afterwards to the Dean and Chapter.[61] During the Civil War, the Vestry, which was strongly committed to the cause of Parliament and radically Puritan, took control. The incumbent, James Palmer, a moderate Puritan, was pressured into accepting voluntary sequestration on 18 October 1645 and the Vestry thereafter appointed a series of preachers closer to their own tastes. Fisher accepted the post of "lecturer" at Bride's on 28 April 1651. Two other short incumbencies followed and Fisher was then "entertained minister" from 30 June 1652 on a salary of 40s. per week[62] – a good rate that reflected his considerable experience and ability. No reason is given for the interlude, but April 1651 seems rather early for Fisher to appear in London, where he was fairly notorious in some quarters. The parish minutes record that:

- a Sacrament be administered by Mr. Fisher on the next Sabbath day come Sennitt in the parishe to suche as have been admitted of formerly to the Eldershipp and to suche that come to give accompt to the Minister and Elders of their faith, as he, Mr. Fisher, hath propounded it.

This relatively restricted admission to Lord's Supper is closely in line with Richard Baxter's demand in that candidates for communion be confronted with the New Covenant and "might knowingly and seriously professe their consent, (and if they subscribed their names, it would be more solemly engaging) and this before they receive the sacrament of the Lord's Supper."[63] It is in clear contrast to the inclusive teaching and practice of Thomas Blake, who engaged in controversy over this issue with Baxter and his circle over several years.[64]

While at Bride's, Fisher delivered funeral orations for two women of the congregation: Mrs Holgate and Mrs Baker. He published these, with an introduction penned on 25 September 1654 at Thornton, under the title: A Love-Token for Mourners: Teaching Spiritual Dumbness and Submission under Gods Smarting Rod.[65] He was described as "Samuel Fisher M.A., late preacher at Bride's, London, now at Thornton in Cheshire." The valedictions were accompanied by An antidote against the fear of death, a reflection he had written during the difficult days of summer 1650 at Shrewsbury, advertised as Some thoughts which the author used to flatter and allure his soul to be well pleased with death, when he with the Rev. Mr. Blake stayed in Shrewsbury (in the time of God's last visitation of that place by the pestilence) to execute their pastoral office amongst their people that did abide there in that doleful time, when they were under the continual expectation of arrest."

The next known appointment at Bride's was of John Herring on 8 October 1654,[62] some months after Fisher had taken up residence at Thornton.

Thornton

%252C_1st_Baron_Delamer_of_Dunham_Massey%252C_Circle_of_Godfrey_Kneller.jpg.webp)

On 25 May 1654[1] Fisher took up the rectory of Thornton-le-Moors, Cheshire, which was in the gift of Sir George Booth of Dunham Massey,[66] a notable landowner who headed the Presbyterian cause in Cheshire and a long-term rival of Brereton, the main local representative of the army.[67] Thornton had seen its share of conflict, both religious and military. Samuel Clarke served there, apparently with some difficulty and discomfort, in the 1620s under Dr George Byron, the Laudian incumbent.[68] When the Parliamentarians triumphed in the Chester area in 1646, Byron, was turned out in favour of the Puritan Richard Chapman.[69] Richard Bowker was ordained and certified by the Manchester classis to be a minister at Thornton on 9 August 1653.[66] He had presented himself for ordination on 12 July, when it was noted: "Mr. Richard Bowker presented himself for ordination. He hath been examined in the languages, in Greek, logic, philosophy, ethics, physics, metaphysicks, and approved; had an instrument given him to be affixed."[70] It seems that he acted as assistant to Fisher, although he later moved to be minister in Middlewich. Fisher was later assisted by Samuel Edgley, a candidate for ordination.[66]

Cheshire never had a classical presbytery,[71] and had been dependent on the Manchester classis for many important functions. A voluntary association was proposed by a meeting of Cheshire ministers at Wilmslow on 14 September 1653, making it contemporary with the association founded by Baxter in Worcestershire.[72] Its establishment was agreed at a meeting in Knutsford the following month.[71] Like Baxter's movement, it was intended to carry some of the ordaining and disciplinary functions left in abeyance by the collapse of the national Presbyterian project in 1648.[73] The workings and extent of the association are unclear but Fisher was closely associated with the leading figures in it and his judgement respected by them. In November 1656 Henry Newcome, one of the founders, had the opportunity of taking up the incumbency of Julian's church in Shrewsbury after losing a valuable post in Manchester. Baxter wrote a detailed and encouraging letter to him, but at the end deferred to Fisher's closer knowledge.

- But then I confess, you have one reason that I am unable to confute, — which is the contrary judgment of your neighbour ministers. They may see more than I can, (especially such as judicious and honest Mr. Fisher, who knoweth both places.) And, therefore, I presume not peremptorily to advise you, but to cast in my thoughts; which, if they seem unsatisfactory to you, reject them.[74]

Newcome and his friend Adam Martindale were among the Presbyterian ministers who knew of the preparations for Booth's Rebellion of August 1659[75] and it seems that there was a wide circle of supporters among the ministers, although no specific evidence of Fisher's position. Although Fisher's patron played an initially farcical role in the events that brought about the Restoration of the monarchy, he was the first chosen of the MPs deputed to carry the Convention Parliament's response to the Declaration of Breda to Charles II.[67] Despite all the hopes of a Presbyterian establishment, Fisher and Edgley were turned out of Thornton in the Great Ejection of 1662.[66] The living was taken by a Mr Shaw, who had been Booth's chaplain but decided to conform to the Act of Uniformity 1662.

Birmingham

Fisher seems to have spent the rest of his life at Birmingham. There he became a leading member of a regional network of nonconformists, who tried to take advantage of the Royal Declaration of Indulgence of 15 March 1672 to gain legal recognition for their meetings. A petition referring to the Indulgence was submitted by Birmingham Presbyterians some time in April.[76]

To the Kings Most Excellent Matie

The humble Addresse & Petitiõ of severall Inhabitants of the Towne of Birmingham in the County of Warwicke in the Name of them &c. and sundry others of the same Towne, humbly sheweth

That your Majestyes gracious declaratiõ of ye 15th of March last past wherein your Maties Indulgence to us is soe fully manifested, is wth all humble thankfulnes acknowledged by us. And professing our Loyalty to your Sacred Matie wth all Sincerity, and resolving, by the grace of God, to use the Liberty, soe freely given to us, with that Moderatiõ & peaceableness, that your Majesty may not have Cause to repent the favour afforded to us therein. Wee are humble Petitioners to yor Sacred Matie, that in pursuance thereof, your Majesty will bee gratiously pleased, to allow and Lycense Mr Samuel Fisher Master in Arts of the Presbiterian perswasiõ to excercise his Ministeriall functiõ amongst us, and that the house of the said Samuel Fisher, and the Town-Hall scituate in Birmingham, may bee places allowed for their meeting under his Ministry

In which Royall, & humbly desired favour to Mr Samuel Fisher and us

Your Majestyes most humble Petitionrs

Shall ever pray.

Tho: Rowney

John Hunt

Francis Himmons

William Egmond

John AshfordGeorge Jackson

Samuel Taylor

Josiah Yate

Isaac Ashford

Daniel Ashford.

At this time the work of co-ordinating requests to government was co-ordinated in part of the West Midlands by Fisher's eldest son, Samuel Fisher junior, and it seems that it was he[77] who, a little later, also sent to London petitions relating to nonconformist communities in Darlaston, Sedgley, and Rowley Regis, as well as a further house in Birmingham.[78] These were all channelled through Robert Blayney, clerk of the Worshipful Company of Haberdashers, allegedly a former confidant of Oliver Cromwell,[79] who handled a large volume of correspondence with government officials for the nonconformists outside London. It is likely that the petition relating to Fisher's Birmingham meetings was accompanied by a covering letter[80] from Charles Fisher, the preacher's younger son, who probably lived in London and was known personally to Blayney. This made clear that the signatories included some of the principal citizens of Birmingham. Samuel junior's letter relating to Darlaston finished with the postscript "I pray remember my fathers business," suggesting there had been some delay in dealing with it.[81] Shortly after, it was returned to Blayney, with an "Endorsed" mark. Licences for Samuel Fisher's house in Birmingham to be a Presbyterian meeting place and for him to operate as a Presbyterian teacher in it were entered in government records on 1 May 1672,[82] along with two of the Staffordshire licences, suggesting Blayner did actually expedite matters for Birmingham when he received the further requests from Samuel junior.[83] Blayney picked up the Birmingham licences two days later.[84]

Last years and death

Fisher seems to have resided in Birmingham until his death. He made his will 8 November 1677, including a bequest to a friend called Richard Blayney.[1]

Fisher was buried on 5 September 1681 at St Martin's, Birmingham.

Marriage and Family

Fisher married but his wife's name is unknown. There were at least three children who survived to adulthood: Samuel junior, Hannah and Charles. Both his wife and Charles had died by the time his will was made in 1677. His chief beneficiary was Hannah, who cared for her parents into old age.

Publications

- An Antidote against the Fear of Death; being meditations in a time and place of great mortality (Shrewsbury, 1650).

- A Love Token for Mourners, teaching spiritual dumbness and submission under God's smarting rod, in two funeral sermons, London, 1655.

- A Fast Sermon, preached 30 January 1692–3.

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Wright, Stephen. "Fisher, Samuel". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9508. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Athenae Oxonienses, pp. 701–3

- ↑ Joseph Foster, Alumni Oxonienses, p. 501, also Bennell-Bloye

- 1 2 Coulton, p. 165, note 43.

- ↑ Villani, Stefano. "Fisher, Samuel". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9507. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ CCEd Record ID: 69926

- 1 2 Rigg, James McMullen (1889). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 19. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ↑ Godfrey, Rectors and vicars.

- ↑ Coulton, pp. 86–7.

- ↑ Coulton, p. 75.

- ↑ Coulton, p. 79.

- ↑ Reliquae Baxterianae, p. 98.

- ↑ Withington Parish Register, p. iv.

- ↑ Gaydon and Pugh (eds.), Houses of Augustinian canons: Abbey of Haughmond

- ↑ Eyton, p. 264.

- ↑ Hope and Brakspear, p. 284.

- ↑ Visitation of Shropshire 1623, Barker of Wollerton, Coulshurst and Haughmond, p. 27.

- 1 2 Portland manuscripts, Volume 3, p. 70.

- 1 2 Visitation of Shropshire 1623, Barker of Wollerton, Coulshurst and Haughmond, p. 28.

- 1 2 3 Coulton, p. 93.

- ↑ CCEd Record ID: 200740

- ↑ CCEd Record ID: 134896

- ↑ Withington Parish Register, p. 17.

- ↑ CCEd Record ID: 120124

- ↑ Palmer, p. 234.

- ↑ CCEd Record ID: 119904

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, Volume 2, pp. 214–5.

- ↑ Coulton, p. 86.

- ↑ Auden (1907), p. 249.

- ↑ Coulton, p. 91.

- ↑ Coulton, p. 94.

- ↑ Coulton, p. 92.

- ↑ House of Commons Journal, Volume 2, 23 January 1643

- ↑ House of Lords Journal, Volume 5, 3 March 1643

- 1 2 Owen and Blakeway, Volume 2, p. 378.

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, Volume 2, p. 281.

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, Volume 2, p. 376.

- ↑ Coulton p. 106.

- 1 2 Coulton, p. 107.

- ↑ Auden (1907), p. 270.

- ↑ Auden, p. 263.

- ↑ The scheme is reproduced in full by Auden, pp. 263–70. and Shaw, pp. 406–12.

- 1 2 3 Gaunt, Peter. "Mackworth, Humphrey". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37716. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Coulton, p. 87.

- ↑ Coulton, p. 108.

- ↑ Auden, pp. 270–1.

- ↑ Auden, p. 267.

- ↑ Auden (1907), p. 242.

- 1 2 Coulton, p. 113.

- ↑ Portland manuscripts, Volume 3, p. 188.

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, Volume 1, p. 465.

- ↑ Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, 1650, 16 August, p. 290.

- ↑ Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, 1650, 23 August, p. 301.

- ↑ Coulton, p. 114.

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, Volume 1, p. 466.

- 1 2 Coulton, p. 115.

- ↑ Auden, p. 265.

- ↑ Gough, p. 178.

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, Volume 2, p. 379.

- ↑ Owen and Blakeway, Volume 2, p. 380.

- ↑ Godfrey, History of St Bride's: The advowson.

- 1 2 Godfrey, History of St Bride's: The seventeenth century to the Great Fire.

- ↑ Richard Baxter, Aphorismes of Justification, p. 107.

- ↑ William, Lamont. "Blake, Thomas (1596/7–1657)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2583. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Urwick, p. 467.

- 1 2 3 4 Urwick, p. 64.

- 1 2 Kelsey, Sean. "Booth, George". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2877. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Urwick, p. 63.

- ↑ Shaw, p. 329.

- ↑ Urwick, p. 167.

- 1 2 Urwick, p. xxxii.

- ↑ Shaw, pp. 152–3.

- ↑ Shaw, p. 159.

- ↑ Autobiography of Henry Newcome, Volume 2, p. 346.

- ↑ Urwick, p. xxxvi.

- ↑ Turner, Original Documents, Volume 1, p. 279, Document 320 (237)

- ↑ Turner, Original Documents, Volume 3, p. 316.

- ↑ Turner, Original Documents, Volume 1, pp. 262–3, Documents 320 (191–3)

- ↑ Turner, Original Documents, Volume 3, p. 475.

- ↑ Turner, Original Documents, Volume 1, pp. 235–6, Documents 320 (112)

- ↑ Volume 3, p. 462.

- ↑ Turner, Original Documents, Volume 1, p. 455, Document E (58)

- ↑ Volume 3, p. 463.

- ↑ Turner, Original Documents, Volume 1, p. 298, Document 320 (302)

References

- Auden, J. E. (1907). "Ecclesiastical History of Shropshire during the Civil War, Commonwealth and Restoration". Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological and Natural History Society. 3. Shropshire Archaeological and Natural History Society. 7: 241–310. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Baxter, Richard (1649). Aphorismes of Justification. London: Francis Tyton. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- Baxter, Richard (1696). Sylvester, Matthew (ed.). Reliquae Baxterianae. London: Parkhurst et al. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- "CCEd search". Clergy of the Church of England Database. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- Coulton, Barbara (2010). Regime and Religion: Shrewsbury 1400–1700. Little Logaston: Logaston Press. ISBN 978-1-906663-47-6.

- Eyton, Robert William (1858). Antiquities of Shropshire. Vol. 7. London: John Russell Smith. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Foster, Joseph, ed. (1891). Alumni Oxonienses, 1500–1714. Vol. 2. London: Parker. Retrieved 1 July 2015. Also at Foster, Joseph, ed. (1891). Alumni Oxonienses, 1500–1714, Faber-Flood. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Gaunt, Peter. "Mackworth, Humphrey". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37716. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Gaydon, A.T.; Pugh, R. B., eds. (1973). A History of the County of Shropshire. Vol. 2. Institute for Historical Research. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Godfrey, Walter H. (1940). Survey of London Monograph 15, St Bride's Church, Fleet Street. Institute for Historical Research. Originally published by Guild & School of Handicraft. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- Gough, Richard (1700). Antiquities & Memoirs of the Parish of Myddle, County of Salop (1895 ed.). Shrewsbury: Adnitt and Naunton. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- Green, Mary Anne Everett, ed. (1876). Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series, 1650. London: Longman. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Helms, M. W.; Hampson, Gillian; Henning, Basil Duke (1983). "Booth, Sir George, 2nd Bt. (1622–84), of Dunham Massey, Cheshire.". In Henning, Basil Duke (ed.). The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1660–1690. Boydell and Brewer.

- Historical Manuscripts Commission, ed. (1894). The Manuscripts of His Grace the Duke of Portland, preserved at Welbeck Abbey. Vol. 3. HMSO. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Hope, William Henry St John; Brakspear, Harold (1909). "Haughmond Abbey, Shropshire". The Archaeological Journal. Archaeological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 66: 281–310. doi:10.1080/00665983.1909.10853116. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Journal of the House of Commons: Volume 2, 1643–1644. Institute of Historical Research. 1802. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- Journal of the House of Lords: Volume 5, 1642–1643. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- Kelsey, Sean. "Booth, George". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2877. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- William, Lamont. "Blake, Thomas (1596/7–1657)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2583. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Newcome, Henry (1852). Parkinson, Richard (ed.). The Autobiography of Henry Newcome, M.A. Vol. 2. Manchester: Chetham Society. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Owen, Hugh; Blakeway, John Brickdale (1825). A History of Shrewsbury. Vol. 2. London: Harding Leppard. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- Owen, Hugh; Blakeway, John Brickdale (1825). A History of Shrewsbury. Vol. 2. London: Harding Leppard. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Palmer, Charles Ferrers (1845). The History of the Town and Castle of Tamworth. Tamworth: Jonathan Thompson. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Phillimore, William Phillimore Watts, ed. (1905). Shropshire Parish Registers: Diocese of Lichfield. Vol. 5. Shropshire Parish Register Society. Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- Rigg, James McMullen (1889). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 19. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Shaw, William A. (1900). A History of the English Church during the Civil Wars and under the Commonwealth, 1640–1660. Vol. 2. London: Longmans, Green. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Tresswell, Robert; Vincent, Augustine (1889). Grazebrook, George; Rylands, John Paul (eds.). The Visitation of Shropshire, taken in the year 1623. Vol. 1. London: Harleian Society. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Turner, G. Lyon, ed. (1911). Original Records of Early Nonconformity under Persecution and Indulgence. Vol. 1. London and Leipzig: T. Fisher Unwin. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Turner, G. Lyon, ed. (1914). Original Records of Early Nonconformity under Persecution and Indulgence. Vol. 3. London and Leipzig: T. Fisher Unwin. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Urwick, William, ed. (1864). Historical Sketches of Nonconformity in the County Palatine of Chester. London and Manchester: Kent and co., Septimus Fletcher. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- Villani, Stefano. "Fisher, Samuel". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9507. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Wood, Anthony A. (1817). Bliss, Philip Bliss (ed.). Athenae Oxonienses. Vol. 3. London. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- Wright, Stephen. "Fisher, Samuel". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9508. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)