Alexander "Sandy" Stoddart FRSE (born 1959) is a Scottish sculptor, who, since 2008, has been the Queen's Sculptor in Ordinary in Scotland and is now the King's Sculptor in Ordinary. He works primarily on figurative sculpture in clay within the neoclassical tradition. Stoddart is best known for his civic monuments, including 10-foot (3.0 m) bronze statues of David Hume and Adam Smith, philosophers during the Scottish Enlightenment, on the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, and others of James Clerk Maxwell, William Henry Playfair and John Witherspoon. Stoddart says of his own motivation, "My great ambition is to do sculpture for Scotland", primarily through large civic monuments to figures from the country's past.[1]

Stoddart was born in Edinburgh and raised in Renfrewshire, where he developed an early interest in the arts and music, and later trained in fine art at the Glasgow School of Art (1976–1980) and read the History of Art at the University of Glasgow. During this time he became increasingly critical of contemporary trends in art, such as pop art, and concentrated on creating figurine pieces in clay. Stoddart associates the lack of form in modern art with social decay; in contrast, his works include many classical allusions.

Biography

Early life

Stoddart's grandfather was an evangelical Baptist preacher, and his parents met through that church.[2] He was born in Edinburgh, though his father, also an artist, moved the family to the village of Elderslie in Renfrewshire, where the young Stoddart immediately noticed the monument there at William Wallace's purported birthplace. Today, Stoddart lives and works in nearby Paisley. At school Stoddart became interested in music (and remains so) but decided he was not good enough to become a professional.[2]

Education

Stoddart went, aged seventeen, to train in fine art at the Glasgow School of Art where he studied from 1976 to 1980. There he settled on sculpture and initially worked within the modernist idiom.[2] Stoddart has recalled an epiphany moment several times: when, after finishing a riveted metal pop-art sculpture (praised by his tutors) he found a bust of the Apollo Belvedere, "I thought my pop-riveted thing was rubbish by comparison. It's extraordinarily easy to pop-rivet two bits of metal together and extraordinarily difficult to make a figure like the Apollo, but I thought I had to try."[2][3]

Stoddart wrote his undergraduate thesis on the life and work of John Mossman, an English sculptor who worked in Scotland for fifty years. His work remains an influence on Stoddart.[4] Stoddart graduated in 1980 with a Bachelor of Arts degree, first class, though he was demoralised by his peers' ignorance of art history: "the name Raphael meant nothing to them". He went on to read History of Art at the University of Glasgow.[2] Afterwards, he worked for six "difficult" years in the studio of Ian Hamilton Finlay.[3] Although Hamilton Finlay is considered one of the most important Scottish artists of the 20th century, Stoddart profoundly disagrees with his working methods: "Finlay was the godfather of a problem that's rampant everywhere today. He called the people who made his work 'collaborators'. What we call them nowadays is 'fabricators'. They're talented people who are plastically capable, but they never meet their 'artist'. They're grateful, desperate and thwarted."[2]

He is an Honorary Professor at the University of the West of Scotland.[5] On 30 December 2008, it was announced that Stoddart had been appointed Her Majesty's Sculptor in Ordinary in Scotland.[6]

Aesthetic viewpoint

Stoddart is deeply critical of modernism and contemporary art, and scornful of "public art", a phrase which makes him search for "a glass of whisky and a revolver".[2] He has repeatedly criticised winners of the Turner Prize, such as Damien Hirst — "there's plenty of them" — and Tracey Emin, whom he calls "the high priestess of societal decline".[2] Stoddart said of his own repeated public denouncements, "Somebody will be exhibiting a bunch of bananas in a gallery, and they'll [radio producers] get me on to talk dirty about it".[2] Stoddart has characterised modern art as dominated by left-wing politics, to the extent that "certain artistic forms likewise became suspect: the tune; the rhyme; the moulding; the plinth" as coercive and overly traditional.[7] He argued that an equestrian statue of the Mariner King, William IV, should be placed on the fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square, as originally intended.[7]

A painting by Titian is like a Leningrad, holding out against the forces of the world... Whereas the art of Tracey Emin is a complete capitulation to the world. Cutting a shark in half and putting it in a tank of piss is just art giving up. I find it very odd when they describe art as challenging, because I always thought art was meant to calm you like a lullaby, not challenge you like some skinhead in an underpass.[7]

He developed an interest in music at school, where he learned to play the piano, which he still does daily. He called his own medium, sculpture, "an art inferior to the super-art of music," and nominated Richard Wagner as the greatest composer.[3] Stoddart developed his theme on the quietism of monumental art and its relation to Schopenhaurian resignation in a lecture to the Wagner Society of Scotland on 2 March 2008.[8]

Stoddart works within the neo-classical tradition of art, and believes that greatness and respect for posterity are important considerations. In 2010 he rebuffed a query about his interest in sculpting a memorial to Bill McLaren, a rugby union broadcaster: "I do not do sportsmen and I certainly do not do sports commentators. I do artists, philosophers and poets", he said, warning that memorials are often hastily erected.[9] Advocates of the memorial described the remarks as insensitive.[9]

Despite their idiomatic differences, Raymond McKenzie argues that the works of both Ian Hamilton Finlay and Stoddart combine formal and intellectual elegance with sharp, sometimes satirical critiques of contemporary society.[10]

Although Stoddart is apprehensive of modern and contemporary art, he considers his work to be part of a more broadly-construed "Modernist" tradition.

"And yet, after having said all this about Modernism, I consider myself a Modernist – but in the context of a vast application of the term extending miles beyond the pokey wee official area to which usually it is confined. For in truth there are really two kinds of Modernism to be uncovered in the space of the last two and a half centuries, and it is to the first and largest of these that I belong and to which, in my small way, I contribute. This is the Modernism that was born in neo-classicism and has, as its great central titan, the mighty Richard Wagner."[11]

Works

Civic monuments

In his own work, Stoddart has developed "heroic-realist" neo-classical representations of historical figures.[5] Stoddart works as a civic-monumentalist for Scotland, and described the need his work fills thus: "We need serious monuments which don't have the Braveheart touch. If we're to be a nation, we need that. Fletcher of Saltoun is absolutely urgent if we're to show we mean business. We don't do it with a stupid Parliament building that looks like a Barcelona-inspired cafeteria. It's a bloody outrage."[3]

He has made sculptures of David Hume and Adam Smith, philosophers of the Scottish Enlightenment, which stand in the Royal Mile in Edinburgh. Hume is depicted in a philosopher's toga, representing the timelessness of philosophical thought, a decision which was criticised as atavistic after the unveiling in 1996, though Stoddart remained stoic, "So here I discovered that the right thing, done in public, will often earn one great disapproval: a lesson for life – in the modern age at least."[2] Local philosophy students soon began a tradition of rubbing the statue's toe to absorb some of his knowledge. Though Stoddart placed the foot over the edge of the plinth to encourage such engagement, the irony of the practice given Hume's critiques of superstition has been remarked upon.[12]

Smith, a philosopher who forged the new discipline of economics, is, by contrast, depicted in contemporary attire, showing his concern for the practical matters of economic activity, a gown draped over his shoulder retains the connection to philosophy and academia.[1] Smith's economic ideas are also encoded into the statue: the plough behind him represents the agrarian economics he supplanted, the beehive before, is a symbol of the industry he predicted would come. His hand, resting on a globe, is obscured by the gown: a literal presentation of Smith's famous metaphor of the invisible hand.[13] The life-and-a-half size statue of Smith, is cast in bronze from a plaster model by the sculptor and was unveiled in 2008. It was funded by private subscriptions organised by the Adam Smith Institute.[14]

Stoddart's statue of James Clerk Maxwell, a physicist, stands in George Street in Edinburgh and a memorial to Robert Louis Stevenson, a novelist, is on Corstorphine Road.[3] His monument to John Witherspoon stands in Paisley, with a copy outside Princeton University.

There are several pieces by Stoddart in Glasgow's Merchant City quarter. Italia, a 2.6 metre, glass re-in-forced polymer statue on top of Ingram Street represents the contribution of Italian traders to the area. Classical in style, the female form is swathed in a chiton and carries symbols of ancient Italy: a palm branch in her right hand and an inverted cornucopia in her left.[15] On John Street, a trio of figures, Mercury, Mercurius and Mercurial form a triangle. The first two, identical figures, sit above the John St. façade of the Italian centre; their English and Roman names signify the two different manifestations of the deity in Roman mythology. Here, they embody a "dialogue" between ancient lore and modern city life. Opposite, on a plinth on the street, stands Mercurial, cast in bronze and with the adjectival form of the name, it complements the duality of the other two with an underlying unity.[16]

Putative projects include a monument to Willie Gallacher, the Paisley-born Communist MP, championed by Tony Benn and funded by a public appeal and "Oscar", an amphitheatre carved into the rock on the Scottish coast dedicated to Ossian, the mythical Scot bard.[3][17]

In 2019 Stoddart made a 14-foot-tall (4.3 m) statue of Leon Battista Alberti for Walsh Family Hall of Architecture of the University of Notre Dame, in the United States, his single tallest work.[18]

Busts, cabinet displays and architectural sculpture

During 2000 to 2002 the Queen's Gallery at Buckingham Palace was renovated in the neo-classical style under the direction of John Simpson, envisioned as "building visible history".[19] For the walls in the two-storied entrance hall, Stoddart made architectural friezes which interpret Homeric themes in twentieth century Britain.[20] For the Sackler Library in Oxford University, he made a 6-by-25-foot (1.8 m × 7.6 m) bronze frieze, depicting an allegory of traditionalist and modernist values.[21] Stoddart has also worked on busts of living figures whom he admires, often fellow-classicists including philosopher Roger Scruton, architects Robert Adam and John Simpson, architectural historian David Watkin, and politician Tony Benn.[1]

In the period 2017-2019 Stoddart worked with architect Craig Hamilton to create a new mausoleum for the Goldhammer family in Highgate Cemetery.[22][23]

Gallery

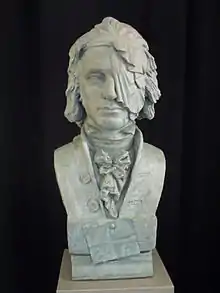

Heroic Bust, Henry Moore by Alexander Stoddart 1992

Heroic Bust, Henry Moore by Alexander Stoddart 1992 Bust of Thomas Muir

Bust of Thomas Muir A Roman copy of the Head of Apollo of the Belvedere in the British Museum

A Roman copy of the Head of Apollo of the Belvedere in the British Museum

Honours and awards

In 2012, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh.[24]

References

Sources

McKenzie, R. Public Sculpture of Glasgow. Liverpool University Press, 2001. ISBN 0853239371

Notes

- 1 2 3 Aslet, Clive. Alexander Stoddart: talking statues Archived 3 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The Daily Telegraph, 12 July 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Jack, Ian. Set in stone Archived 14 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian. 6 June 2009. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Alexander Stoddart interview: 'I believe in the elite for all'. The Scotsman, 22 November 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ Nisbet, Gary. "Alexander (Sandy) Stoddart". Glasgow – City of Sculpture. Archived from the original on 14 August 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- 1 2 "Alexander Stoddart CV". Archived from the original on 20 January 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ↑ No ordinary sculptor Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. The Scottish Government. 30 December 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 Stoddart, Alexander. How the West Was Won. The Spectator, 28 June 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ↑ Vol. 12. No. 1, February 2008, Wagner Society of Scotland Newsletter, Forthcoming Events. "An Evening With Alexander Stoddart". Archived from the original on 29 November 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 "Sculptor sneers at Bill McLaren tribute by Marc Horne". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- ↑ McKenzie (2001:499).

- ↑ "Interview with Alexander Stoddart". Manner of Man Magazine. Retrieved 22 July 2012.

- ↑ Wiseman, Richard. It moved me:Statue of David Hume on the Royal Mile Archived 3 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The Times, 29 March 2009. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- ↑ A monument to Adam Smith Archived 3 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Adam Smith Institute. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ↑ Crowd sees Smith statue unveiled. BBC News, 4 July 2008. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ↑ McKenzie (2001:215).

- ↑ McKenzie (2001:216).

- ↑ "Adam Smith by Sandy Stoddart". Morris Singer Art Founders. Archived from the original on 6 August 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ↑ "From Paisley to Indiana: Scottish sculptor unveils epic new work for the University of Notre Dame". The Herald. Glasgow. 25 February 2019. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ↑ "The Queen's Gallery". Jubilee Journal. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ↑ Grafton, A. et al. The Classical Tradition. Harvard University Press: Cambridge (2010), p. 632.

- ↑ Architectural sculpture. Archived 5 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine www.alexanderstoddart.com. Retrieved 4 November 2010.

- ↑ https://architecturefoundation.org.uk/tours/building-tour-goldhammer-sepulchre-with-craig-hamilton

- ↑ RIBA Journal 16 June 2017

- ↑ "Dr Alexander Stoddart FRSE". The Royal Society of Edinburgh. Archived from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 26 June 2018.