Contemporary view of the central part of the sanctuary | |

| Location | Akrai |

|---|---|

| Region | Sicily |

The Santoni are a collection of statues carved into a rock face near Palazzolo Acreide, the ancient Akrai, in Sicily.

The statues are the remains of a sanctuary for one of the most mysterious cults of antiquity, the cult of Magna Mater. Although very badly preserved, the site is unique for its scale and for the completeness of the sculptures. It is believed to have been the principal centre of the cult of the goddess Cybele in Sicily.[1]

For stylistic reasons and as a result of archaeological discoveries in the surrounding area, the sanctuary has been dated by scholars to around the fourth or third centuries BC.[1]

Location

The hill on which Akrai was founded had been inhabited since very ancient times. In fact, on its northern slope, a shelter under the rock has yielded abundant evidence of stone age material which shows all the characteristics of the Upper Palaeolithic and is to this day the oldest securely identified habitation in all Sicily.

Thucydides reports that Akrai was founded in 665/4 BC by the Syracusans on a plateau bounded by steep cliffs and by four streams, from which all routes of access could be dominated.[2] The city guaranteed free communication between Syracuse, the Greek cities on the southern coast of Sicily and the Sicel cities in the interior.

During the fourth and fifth centuries AD, Akrai is mentioned as the most important Christian centre of eastern Sicily after Syracuse itself, as affirmed by the vast catacombs found there. It is not known when the city ceased to exist, but the historian Michele Amari suggested that its destruction occurred in 827, during the Islamic conquest of Sicily.[3] The medieval Palazzolo Acreide, the nearest settlement to Akrai, is mentioned for the first time in the geography of Edrisi.[4]

Description

The large sanctuary complex is located along the south side of Orbo Hill, on a rocky outcrop overlooking a path with two flat semi-circular areas at each end. Circular stones, which are probably altars, are visible in the two semi-circular areas and along the path.

The sculptures are found in twelve wide niches carved into the rock, eleven on one level and another one on a lower level. Other smaller niches with no images complete the structure, which has a regular architectural design, indicating that it was a single sanctuary rather than a collection of votive reliefs.[1] The discovery of lamps and small paterae supports the identification of the site as the seat of a cult.[5]

In eleven of the niches the image of the goddess is depicted enthroned with other figures surrounding her. In the twelfth niche she is depicted standing on her feet at life size.

The identification of the goddess in the niches as Cybele (Magna Mater) derives from the comparison of the iconography with representations of her elsewhere in the Greek world, particularly at Athens.[1][5] The goddess is depicted with a pleated chiton and a himation gathered over her left shoulder and falling to her knees. Her hair is in a "melon-like" style with two long ringlets falling down over her shoulders and a modius on her head. At her sides, there are two lions in heraldic positions. A patera is clearly visible in the right hand of some of the sculptures and a tympanum in the left hand. In other sculptures these implements cannot be made out, but the general similarity between the reliefs and light traces of figural relief suggest that they were once present.

Two iconographic postures are used: that of the goddess seated on her throne, often within a naiskos (shrine), which is characteristic of north Ionic and south Aeolic depictions; and that of the goddess standing upright, which is more typical of southern Ionia. Both models can be seen also in Phrygian rural sculpture and in some parts of Asia Minor very similar and nearly contemporary depictions can be found in rural sanctuaries of Magna Mater. The closest parallels are the sanctuary of Meter Steunene of the Aizanoi in Phrygia, the small sanctuary of Kapikaya near Pergamon and the sacred complex of Panajir Dagh near Ephesus.

Minor figures are depicted next to the goddess Cybele in about five of the niches (the poor state of conservation makes it impossible to exclude the possibility that there were originally more of these minor figures). These include Hermes, Attis, Hecate, the Dioscuri, the Galli and the Corybantes. Although the connection of these figures with the goddess can be reconstructed from many literary, epigraphic and monumental sources, the simultaneous presence of all of them is an absolutely unique feature of the Santoni, which is not known from any other example.[1] Three iconographic schemata can be recognised in the combination of these minor figures, each of which is related to specific religious motifs known from Hellenistic and Roman monuments.

The first schema is employed in five of the reliefs and is characterised by the Galli (mythic and ritual priests of the goddess) and the Corybantes (mythical companions of the Galli), depicted as two small figures on either side of Cybele's head. They wear tunics, often with an overcloak and a Phrygian cap and carry their identifying symbols: a tympaneum in their left hand and a rod in their right.

The combination of Cybele, Hermes and Attis seen in another relief is the second iconographic schema known from other Greek depictions. In this relief which is largely intact, Cybele is in an unusual position, standing with her arms outstretched with her left hand on Attis' head and her right hand on Hermes' head, in a protective gesture. Hermes and Attis are recognisable by their attributes (the caduceus and the shepherd's staff respectively) and by their crossed legs.

To the right of Attis a female individual is depicted who is very poorly preserved - only her broad contours and some drapery can be made out properly. She appears to be walking and holding an object in her left hand, which might be a long torch of the sort carried by Hecate Dadophora. This connects to a third iconographical schema known from Hellenistic and Roman monuments: the divine triad of Cybele, Hermes and Hecate.

There is another element worthy of note in this relief: two individuals riding on large horses - probably the Dioscuri, who are also associated with the Magna Mater and her mysteries in epigraphic and artistic sources.

In the richness and complexity of their depictions, the Santoni offer, therefore, a sort of synthesis of the iconography and religious ideas connected to the Magna Mater's cult. The uniqueness of the monument lies primarily in the presence of so many of the individuals which are connected to her in disparate literary, epigraphic and artistic sources. In no other known case are so many found in a single composition.[1]

Excavation and scholarship

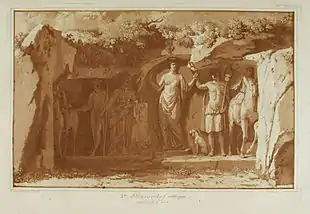

The Santoni were mentioned for the first time by Ignazio Paternò Castello, Prince of Biscari, in his 1781 book, Viaggio per tutte le antichità della Sicilia[6] and again a few years later by the French artist Jean-Pierre Houël who provided a description and classicising reconstructions.[7] Houel's images are not accurate and, along with his interpretation of the Santoni as funerary sculptures, they led later scholars to erroneous conclusions. For example, in the picture from Houel at right, the lions which flank the goddess are instead depicted as dogs (encouraging a viewer to identify her as Artemis).

Proper archaeological investigation began in the nineteenth century, with the work of Baron Gabriele Iudica, royal custodian of antiquities in the Valle di Noto, who went looking for the tombs that Houel had published and found the other groups of sculptures, a paved path, and objects like lamps and small paterae.[8] Iudica shared the interpretation of Houel, considering the sculptures to be funerary monuments.

In 1840, Domenico Lo Faso, Duke of Serradifalco published a description of the site with illustrations by Francesco Saverio Cavallari and, following the interpretation of the Santoni as funerary monuments, identified the main figure as Isis-Persephone. This theory was followed in the next century by Paolo Orsi and by Pace who interpreted the sculptures as Demeter and Kore - the two Sicilian divinities par excellence.

The authority of the last two scholars long overwhelmed the alternative opinion of Alexander Conze who, using Cavallari's illustrations, first made the connection between the Santoni and Anatolian and Greek depictions of Cybele.[9]

In excavations by the Superintendency of Antiquities in 1953, Rosario Carta produced precise illustrations of the sculptures and Prof. Luigi Bernabò Brea took photographs which were published in a volume which allowed the sanctuary to be seen in the wider context of the diffusion of the cult of Cybele through the Greco-Roman world.[5]

The recognition of the unified structure of the site, however, was only established by the detailed study of Prof. Giulia Sfameni Gasparro, who through the comparison of a wide series of documents relating to the religious and historical context in which the sanctuary belongs, reconstructed the meaning of the sanctuary as far as its poor state of conservation allows in her book I Culti Orientali in Sicilia.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Giulia Sfameni Gasparro, "I culti orientali in Sicilia", Leiden, E.J. BRILL, 1973. Cap. II, pp 126-149 & tab. LXVI-CIV. ISBN 9004035796.

- ↑ Thucydides 6.5

- ↑ Michele Amari, "Storia dei Musulmani in Sicilia", Firenze, 1854.

- ↑ "L'Italia descritta nel “Libro di Re Ruggero” compilato da Edrisi", translated by M. Amari & C. Schiaparelli, Roma, 1883.

- 1 2 3 Luigi Bernabò Brea, Akrai, La Cartotecnica, Catania, 1956

- ↑ Ignazio Paternò Principe di Biscari, Viaggio per tutte le antichità della Sicilia, Napoli, 1781 (3ª ed., Palermo 1817).

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Houël, Voyage Pittoresque des Isles de Sicilie, de Malte, et de Lipari, 4 vol., Paris, 1787, Vol. III, 1785, pp 112-114 e tavv. 196-198.

- ↑ Gabriele Iudica, Real custode delle antichità del Val di Noto, Le antichità di Acre, scoperte, descritte e illustrate, Messina 1819.

- ↑ Alexander Conze, "Hermes Cadmilos", Arch. Zeit. 38, 1880, pp. 1-10

Bibliography

- Amari, Michele. Storia dei Musulmani in Sicilia, Firenze, 1854.

- Bernabò Brea, Luigi. Akrai, La Cartotecnica, Catania, 1956.

- Conze, Alexander. "Hermes Cadmilos", Arch. Zeit. 38, 1880, pp. 1–10.

- Houel, Jean. Voyage Pittoresque des Isles de Sicilie, de Malte, et de Lipari, 4 vol., Paris, 1787, Vol. III, 1785, pp 112–114 and tables 196-198.

- Iudica, Gabriele, Real custode delle antichità del Val di Noto, Le antichità di Acre, scoperte, descritte e illustrate, Messina 1819.

- Paternò, Ignazio, Prince of Biscari. Viaggio per tutte le antichità della Sicilia, Napoli, 1781 (3rd ed., Palermo 1817).

- Sfameni Gasparro, Giulia, I culti orientali in Sicilia, Leiden, E.J. BRILL, 1973. Chap. II, pp 126–149 and tables LXVI-CIV. ISBN 9004035796.

- "L'Italia descritta nel “Libro di Re Ruggero” compilato da Edrisi", translated by M. Amari e C. Schiaparelli, Roma, 1883.