| Qing invasion of Joseon | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Korean–Jurchen conflicts, Ming-Qing transition | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 80,000–90,000 | 100,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | |

|---|---|

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Byeongja Horan |

| McCune–Reischauer | Pyŏngcha Horan |

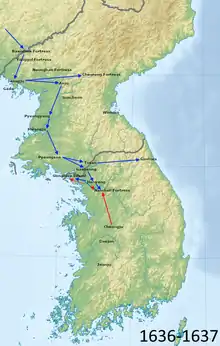

The Qing invasion of Joseon (Korean: 병자호란; Hanja: 丙子胡亂) occurred in the winter of 1636 when the newly established Qing dynasty invaded the Joseon dynasty, establishing the former's status as the hegemon in the Imperial Chinese Tributary System and formally severing Joseon's relationship with the Ming dynasty. The invasion was preceded by the Later Jin invasion of Joseon in 1627.

The invasion resulted in a Qing victory. Joseon was forced to establish a tributary relationship with the Qing Empire, as well as cut ties with the declining Ming. The crown prince of Joseon along with his younger brother were taken as hostages, but they came back to Joseon after a few years. One of the two later became the King Hyojong. He is best known for his plan for an expedition to the Qing dynasty.

Names

In Korean, the Qing invasion (1636–1637) is called 'Byeongja Horan' (병자호란), where 1636 is a 'Byeongja' year in the sexagenary cycle and 'Horan' means a disturbance caused by northern or western foreigners, from 胡 (ho; northern or western, often nomadic barbarians) + 亂 (ran; chaos, disorder, disturbance, turmoil, unrest, uprising, revolt, rebellion).[2]

Background

The Kingdom of Joseon continued to show ambivalence toward the Qing dynasty after the invasion in 1627. Later Jin accused Joseon of harboring fugitives and supplying the Ming army with grain. In addition, Joseon did not recognize Hong Taiji's newly declared dynasty. The Manchu delegates Inggūldai and Mafuta received a cold reception in Hanseong, and King Injo refused to meet with them or even send a letter, which shocked the delegates. A warlike message to Pyongan Province was also carelessly allowed to be seized by Inggūldai.[3]

The beile (Qing princes) were furious with Joseon's response to Qing overtures and proposed an immediate invasion, but Hong Taiji chose to conduct a raid against Ming first. At one point the Qing forces under Ajige got as close to Beijing as the Marco Polo Bridge. Although they were ultimately repelled, the raid made it clear that Ming defenses were no longer fully capable of securing their borders. After this successful operation, Hong Taiji turned towards Joseon and launched an attack in December 1636.[3]

Prior to the invasion, Hong Taiji sent Abatai, Jirgalang, and Ajige to secure the coastal approaches to Korea, so that Ming could not send reinforcements.[4] The defector Ming mutineer Kong Youde, ennobled as the Qing dynasty's Prince Gongshun, joined the attacks at Ganghwa Island and Ka Island. The defectors Geng Zhongming and Shang Kexi also played prominent roles in the Korean invasion.[4]

Diplomatic front

After the 1627 invasion, Joseon maintained a nominal but reluctant friendship with Later Jin. However, the series of events involving three countries (Joseon, Later Jin, and Ming) caused the deterioration of the relationship between Later Jin and Joseon.

Defection of the Ming generals Kong and Geng

Having previously defected to the Later Jin by the end of the Wuqiao mutiny, Kong Youde and Geng Zhongming assisted the Qing with sizable forces numbering 14,000 soldiers and 185 warships under their command. Appreciating the usefulness of their navy in future war effort, Later Jin offered highly favorable terms of service to Kong and Geng and their forces.[5]

Joseon received conflicting requests for aid from both Later Jin and Ming during the mutiny. An official letter of installation of King Injo's late father (Prince Jeongwon) from the Ming government resulted in Joseon siding with Ming and supplying their soldiers only. This gave Later Jin the impression that Joseon would side with Ming when in decisive engagements and suppressing Joseon became a prerequisite for a future successful campaign against Ming. In addition, the naval strength of the Ming defectors gave Later Jin leaders confidence that they could easily strike Joseon leadership even if they evacuated to a nearby island such as Ganghwa. This provided Later Jin with military background in maintaining a strong position against Joseon.[6]

Inadequate war preparation of Joseon

First, a Ming envoy, Lu Weining, visited Joseon in June 1634 to preside over the installation ceremony of the crown prince of Joseon. However, the envoy requested an excessive bribe in return for the ceremony. In addition, quite a few Ming merchants who accompanied the envoy sought to make a huge fortune by forcing unfair trades upon their Joseon counterparts. This envoy visit eventually cost Joseon more than 100,000 taels of silver.[7]

Having accomplished the installations of both his father Prince Jeongwon and his son with help from the Ming, King Injo now attempted to relocate the memorial tablet of his late father into the Jongmyo Shrine. As Prince Jeongwon had never ruled as the king, this attempt was met with severe opposition from government officials, which lasted until early 1635. Adding to this, the mausoleum of King Seonjo was accidentally damaged in March 1635 and the political debate about its responsibility continued for the next few months. These political gridlocks prohibited Joseon from taking sufficient measures to prepare for a possible invasion from Later Jin.[8][9]

Severance of diplomatic relations

In February 1636, Later Jin envoys led by Inggūldai visited Joseon to participate in the funeral of Joseon's late queen. However, as the envoys included 77 high-ranking officials from the recently conquered Mongolian tribes, the real purpose of the envoys was to boast the recent expansion of the Later Jin sphere of influence and examine the opinion of Joseon about the upcoming ascension of Hong Taiji as the "Emperor". The envoys informed King Injo about their ever-growing strength and requested celebration of Hong Taiji's ascension from Joseon.

This greatly shocked Joseon, as the Ming Emperor was the only legitimate emperor from their perspective. It was followed by extremely hostile opinions growing towards Later Jin in both government and non-government sectors. Envoys themselves had to go through life-threatening experiences as Sungkyunkwan students called for their execution and fully armed soldiers loitered around the places in the itinerary of the envoys. Finally, the envoys wore forced to evacuate from Joseon and return to Later Jin territory. The diplomatic relationship between Later Jin and Joseon was virtually severed.[10]

Hong Taiji became the Emperor in April 1636 and changed the name of his country from Later Jin to Qing. Envoys from Joseon who were at the ceremony refused to bow to the emperor. Although the emperor spared them, the Joseon envoys had to carry his message home. The message included denunciation of the past Joseon activities that were against the interest of Later Jin/Qing and also declared the intention of invading Joseon unless Joseon showed willingness to alter its policy by providing one of Joseon's princes as hostage.[11]

After confirming the message, hardliners against Qing gained voice in Joseon. They even requested execution of the envoys for failing to immediately destroy the message in front of Hong Taiji himself. In June 1636, Joseon eventually transmitted their message to Qing, which blamed Qing for the deteriorating relations between the two nations.[12]

Eve of battle

Now, preparation for war was all that remained for Joseon. Contrary those who supported a war, officials who suggested viable plans and strategies were not taken seriously. Instead,King Injo, afraid of head-on clash with the mighty Qing army, listened to the advice of Choe Myeong-gil and Huang Sunwu, a Ming military advisor, and decided to dispatch peace seeking messengers to Shenyang in September 1636. Although the messengers gathered some intelligence about the situation in Shenyang, they were denied a meeting with Hong Taiji. This further enraged hardliners in Joseon and led to the dismissal of Choe Myeong-gil from office. Although King Injo dispatched another team of messengers to Shenyang in early December, this was after the execution of the Qing plan to invade Joseon on November 25.[13]

War

On 9 December 1636, Hong Taiji led Manchu, Mongol, and Han Chinese Banners in a three pronged attack on Joseon. Chinese support was particularly evident in the army's artillery and naval contingents.[4]

Im Gyeong-eop with 3,000 men at the Baengma Fortress in Uiju successfully held off attacks by the 30,000 strong western division led by Dodo. Dodo decided not to take the fortress and passed it instead. Similarly elsewhere Manchu forces of the main division under Hong Taiji bypassed northern Joseon fortresses as well. Dorgon and Hooge led a vanguard Mongol force straight to Hanseong to prevent King Injo from evacuating to Ganghwa Island like in the previous war. On 14 December, Hanseong's garrisons were defeated and the city was taken. Fifteen thousand troops were mobilized from the south to relieve the city, but they were defeated by Dorgon's army.[1]

King Injo, along with 13,800 soldiers, took refuge at the Namhan Mountain Fortress (Namhansanseong) which did not have enough provisions stockpiled for such a large number of people.[14] Hong Taiji's main division, 70,000 strong, laid siege to the fortress. Provincial forces from around the country began moving in to relieve King Injo and his small retinue of defenders. Forces under Hong Myeong-gu and Yu Lim, 5,000 strong, engaged 6,000 Manchus on 28 January. The Manchu cavalry attempted frontal assaults several times but was turned back by heavy musket fire. Eventually they circumnavigated a mountain and ambushed Hong's troops from the rear, defeating them. Protected by the mountainous terrain, Yu's forces fared better and successfully decimated the Manchu forces after defeating their attacks several times throughout the day. The Joseon troops within the fortress, which consisted of both capital and prefectural armies, also successfully defended the fortress against Manchu assaults, forcing their actions to be relegated to small-scale clashes for a few weeks.[15]

Despite working on tight rations by January 1637, the Joseon defenders were able to effectively counter Manchu siegeworks with sorties and even managed to blow up the powder magazine of an artillery battery that was assailing the East Gate of the fortress, killing its commander and many soldiers. Some walls crumbled under repeated bombardment, but were repaired overnight. Despite their successes, Dorgon occupied Ganghwa Island on 27 January, and captured the second son and consorts of King Injo. King Injo surrendered the day after.[16]

The surrendering delegation was received at the Han River, where King Injo turned over his Ming seals of investiture and three pro-war officers to Qing, as well as agreeing to the following terms of peace, which required Joseon to:[2]

- stop using the Ming era name, and abandon the use of the Ming seal, imperial patent, and jade books.

- send King Injo's first and second sons (Yi Wang and Yi Ho), as well as the sons or brothers of ministers as hostages to Shenyang.

- accept the Qing calendar.

- accept Qing as tributary overlord.

- send troops and supplies to assist Qing in the war against Ming.

- supply warships for transporting Qing soldiers.

- encourage ministers of Joseon and Qing to become related by marriage.

- deny entry to refugees from Qing territory.

- no longer build & rebuild fortresses.

Hong Taiji set up a platform in Samjeondo in the upper reach of the Han River.[17] Injo of Joseon kneeling thrice and bowed nine times, as was customary with the other subjects of the Qing court. Then he was called to eat with the others, sitting the closest to the left of Hong Taiji, higher than even the Hošo-i Cin Wang.[18] A monument in honor of the so-called excellent virtues of the Manchu Emperor was erected at Samjeondo, where the ceremony of submission had been conducted. In accordance with the terms of surrender, Joseon sent troops to attack Ka Island at the mouth of the Yalu River.

Ming officer Shen Shikui was well ensconced in Ka Island's fortifications and hammered his attackers with heavy cannon for over a month. In the end, Ming and Joseon defectors including Kong Youde landed 70 boats on the eastern side of the island and drew out his garrison in that direction. On the next morning, however, he found that the Qing—"who seem to have flown"—had landed to his rear in the northwest corner of the island in the middle of the night. Shen refused to surrender, but was overrun and beheaded by Ajige. Official reports put the casualties as at least 10,000, with few survivors. The Ming general Yang Sichang then withdrew the remaining Ming forces in Korea to Denglai in northern Shandong.[4]

Aftermath

Many Korean women were kidnapped and raped at the hands of the Qing forces, and as a result were not welcomed by their families even if they were released by the Qing after being ransomed. Divorce demands rose, causing social unrest, but the government rejected the divorce requests and said the repatriated women should not be regarded as having been disgraced.[19] In 1648 Joseon was forced to provide several royal princesses as concubines to the Qing regent Prince Dorgon.[20][21][22][23] In 1650 Dorgon married the Joseon Princess Uisun (義順公主), the daughter of Prince Geumnim, who had to be adopted by King Hyojong beforehand.[24][25] Dorgon married another Joseon princess at Lianshan.[26]

Koreans continued to harbor a defiant attitude towards the Qing dynasty in private while they officially yielded obedience and sentiments of Manchu "barbarity" continued to pervade Korean discourse. Joseon scholars secretly used Ming era names even after that dynasty's collapse and some people thought that Joseon should have been the legitimate successor of the Ming dynasty and Chinese civilization instead of the "barbaric" Manchu's Qing. Despite the peace treaty forbidding construction of fortresses, fortresses were erected around Hanseong and in the northern region. The future Hyojong of Joseon lived as a hostage for seven years in Mukden (Shenyang). He planned an invasion of Qing called Bukbeol (북벌, 北伐, Northern expedition) during his ten years on the Joseon throne, though the plan died with his death on the eve of the expedition.[27]

From 1639 until 1894, the Joseon court trained a corps of professional Korean-Manchu translators. They replaced earlier interpreters of Jurchen, who had been trained using textbooks in the Jurchen script. Joseon's first textbooks of Manchu were drawn up by Shin Gye-am, who had previously been an interpreter of Jurchen, and he transliterated old Jurchen textbooks into the Manchu script.[28] Shin's adapted textbooks, completed in 1639, were used for the yeokgwa (special examinations for foreign languages) until 1684.[28] The Manchu examination replaced the Jurchen examination, and the examination's official title was not changed from "Jurchen" to "Manchu" until 1667.[28]

For much of Joseon's historical discourse following the invasion, the Qing invasion was seen as a more important event than the Japanese invasions of Korea from 1592 to 1598, which, while devastating, had not ended in complete defeat for Joseon. The defeat at the hands of the "barbarian" Manchus, the humiliation of the Joseon kings and Yi family, as well as the destruction of the Ming dynasty, had a deeper psychological impact on contemporary Korean society than the Japanese invasions. The Japanese invasions had not created a fundamental change in the Ming world order of which Joseon had been part. It was only after the rise of Japan during the 19th century and the following invasion and annexation of Korea that the 16th-century Japanese invasions by Toyotomi Hideyoshi became more significant.[27]

Popular culture

- The novel Namhansanseong by South Korean novelist Kim Hoon is based on the second invasion.[29]

- The 2009 musical, Namhansanseong, is based on the novel of the same name, but focuses on the lives of common people and their spirit of survival during harsh situations. It stars Yesung of boy band Super Junior as villain "Jung Myung-su", a servant-turned-interpreter. It was shown from 9 October to 14 November at Seongnam Arts Center Opera House.[30]

- The 2011 South Korean movie War of the Arrows is based on an event in which Choe Nam-yi risked his life to save his sister.

- The 2015 south korean drama Splendid politics.

- The 2017 South Korean movie The Fortress is based on real historical events during the Qing invasion of Joseon.

- The 2023 South Korean TV series My dearest tells the story of events of this invasion using two pairs of fictional lovers, and placing them as protagonists in key events of the invasion and its aftermath.

See also

References

Citations

- 1 2 Kang 2013, p. 151.

- 1 2 "병자호란(丙子胡亂) Byeongjahoran". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- 1 2 Swope 2014, p. 114.

- 1 2 3 4 Swope (2014), p. 115.

- ↑ Swope 2014, p. 101.

- ↑ Han, Myungki (2008-03-12). "Re-reading Byeongja Horan". No. 62.

- ↑ Han, Myungki (2008-03-19). "Re-reading Byeongja Horan". No. 63.

- ↑ Han, Myungki (2008-03-26). "Re-reading Byeongja Horan". No. 64.

- ↑ Han, Myungki (2008-04-02). "Re-reading Byeongja Horan". No. 65.

- ↑ Han, Myungki (2008-04-30). "Re-reading Byeongja Horan". No. 69.

- ↑ Han, Myungki (2008-05-07). "Re-reading Byeongja Horan". No. 70.

- ↑ Han, Myungki (2008-05-21). "Re-reading Byeongja Horan". No. 72.

- ↑ Han, Myungki (2008-05-28). "Re-reading Byeongja Horan". No. 73.

- ↑ Kang 2013, p. 152-153.

- ↑ Kang 2013, p. 154.

- ↑ Kang 2013, p. 154-155.

- ↑ Hong-s?k O (2009). Traditional Korean Villages. Ewha Womans University Press. pp. 109–. ISBN 978-89-7300-784-4.

- ↑ Jae-eun Kang (2006). The Land of Scholars: Two Thousand Years of Korean Confucianism. Homa & Sekey Books. pp. 328–. ISBN 978-1-931907-30-9.

- ↑ Pae-yong Yi (2008). Women in Korean History 한국 역사 속의 여성들. Ewha Womans University Press. pp. 114–. ISBN 978-89-7300-772-1.

- ↑ Hummel, Arthur W., ed. (1991). Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing period : (1644 - 1912) (Repr. ed.). Taipei: SMC Publ. p. 217. ISBN 9789576380662.

- ↑ Wakeman, Frederic Jr. (1985). The great enterprise : the Manchu reconstruction of imperial order in seventeenth-century China (Book on demand. ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 892. ISBN 9780520048041.

dorgon korean princess.

- ↑ Dawson, Raymond Stanley (1976). Imperial China (illustrated ed.). Penguin. p. 306. ISBN 9780140218992.

- ↑ Hummel, Arthur W. Sr., ed. (1943). . Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office.

- ↑ 梨大史學會 (Korea) (1968). 梨大史苑, Volume 7. 梨大史學會. p. 105.

- ↑ The annals of the Joseon princesses.

- ↑ Kwan, Ling Li. Transl. by David (1995). Son of Heaven (1. ed.). Beijing: Chinese Literature Press. p. 217. ISBN 9787507102888.

- 1 2 Lee 2017, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Song Ki-joong (2001). The Study of Foreign Languages in the Chosŏn Dynasty (1392-1910). Jimoondang. p. 159. ISBN 8988095405.

- ↑ Koh Young-aah "Musicals hope for seasonal bounce" Korea Herald. 30 March 2010. Retrieved 2012-03-30

- ↑ "2 Super Junior members cast for musical" Asiae. 15 September 2009. Retrieved 2012-04-17

Bibliography

- Kang, Hyeok Hweon (2013), "Big Heads and Buddhist Demons: The Korean Musketry Revolution and the Northern Expeditions of 1654 and 1658" (PDF), Journal of Chinese Military History, 2, archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-10-02, retrieved 2019-04-24

- Kang, Jae-eun (2006). The Land of Scholars: Two Thousand Years of Korean Confucianism. Translated by Suzanne Lee. Homa & Sekey Books. ISBN 1931907307. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Lee, Ji-Young (2017), China's Hegemony: Four Hundred Years of East Asian Domination, Columbia University Press

- O, Hong-sŏk (2009). Traditional Korean Villages. Vol. 25 of The spirit of Korean cultural roots(Volume 25 of Uri munhwa ŭi ppuri rŭl chʻajasŏ). Ewha Womans University Press. ISBN 978-8973007844. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Swope, Kenneth M. (2014), The Military Collapse of China's Ming Dynasty, 1618–44, Abingdon: Routledge, ISBN 9781134462094.

- Yi, Pae-yong (2008). Women in Korean History 한국 역사 속의 여성들 (illustrated ed.). Ewha Womans University Press. ISBN 978-8973007721. Retrieved 10 March 2014.