| Batang uprising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Chiefdom of Batang Chiefdom of Litang Batang Monastery Samphel Monastery |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Tashi Gyaltsen Drakpa Gyaltsen Sonam Dradul † Atra Khenpo Phurjung Tawa |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Tibetan Khampa tribesmen, Tibetan Chieftain defectors from Qing army |

Eight Banners | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown Khampa casualties | Feng Quan, unknown Qing casualties | ||||||

The Batang uprising (Chinese: 巴塘事變) was an uprising by the Khampas of Kham against the assertion of authority by Qing China.

The uprising began as an opposition to the new policies of land reclamation and limits of the monastic community. The policies were implemented by Feng Quan, Qing's assistant amban to Tibet, stationed in Chamdo (in western Kham).[3][lower-alpha 1] Feng Quan was murdered in the uprising and [3] four French Catholic missionaries, perceived as Qing allies, fell victim to mobs led by lamas. One was killed immediately (his remains were never found), another was tortured for twelve days before he was executed, while the other two were pursued for three months and beheaded upon capture.[3] Ten Catholic churches were burned down and a mass of locals that had converted to Catholicism were killed.[3] Under French pressure to protect missionaries and domestic pressure to stop the threat of the British invading from the west frontier,[4] Feng Quan's successor Zhao Erfeng led a bloody punitive campaign to quell the uprising in 1906. Zhao brought political, economic, and cultural reform to Batang and the rest of Kham.[4] Direct rule of Batang under Qing was established by Zhao. With the 1911 Chinese Revolution, Zhao was murdered in turn and the status quo ante was reestablished.

Background

Power structure of Batang

The Batang town in Kham was at the frontier of Qing China where authority was shared between local Kham chiefs and local Tibetan Buddhist monastery. The lamas in the monastery were under the suzerainty of Lhasa, Tibet. While Kham chiefs as well as Tibet were under the Qing rule, the Qing authority over Tibet was weak.

The role of the British and the Qing

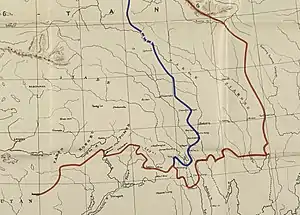

The British expedition to Tibet in 1904 had repercussions in the frontier region between Tibet and China (called "March country" or "Marches").[5] A Qing intervention within Tibet's frontier east of the Dri River (upper Yangtze river, also called Jinsha) was triggered in an effort to open up Tibet's frontier roads to Qing forces.

The role of the French missionaries

Tibetan Khampas in the frontier marches are known for their hostility towards outsiders, and for their strong devotion to their monasteries from specific schools of Tibetan Buddhism, and to the Dalai Lamas.[6]

Decades before the Batang uprising, around 1852 the French Catholic Marist missions from Paris Foreign Missions Society, operating under Qing China's protectorate and ushered into Kham's frontier region, were "[d]riven back from the frontier and forced to withdraw to the Western confines of the Chinese provinces of Sichuan and Yunnan," where they "vegetated for a century within small Christian communities", until expelled by Communist China in 1952.[7][8][9]

From 1873 to 1905, there were five attacks on churches (this Batang uprising being the fifth), known as "missionary cases" in historiography.[10] Upon the complaint of the French consul, the Foreign Ministry of Qing settle the cases and gradually got involved into Batang politics.[10]

Feng Quan's reform

Qing China sent Feng Quan as the new Qing's assistant amban,[3] stationing him in Chamdo.[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] Qing emperor instructed him to develop, assimilate, and bring the Kham regions under strong Qing central control.[11][12] Feng Quan began initiating land reforms among traditional autonomous polities of kingdoms governed by warrior chiefs, and initiating a reduction to the number of monks, whose monasteries were among the autonomous polities.[13][14][6] Feng Quan recruited Chinese soldiers and Sichuan farmers to convert idle land in Batang to cultivable land in the hope of attracting settlers.[15]

Batang battles

The Chiefdoms of Batang and Litang and the Tibetan monasteries rose up. 26–27 March 1905 marked the first bloodshed when a handful of Sichuan farmers were killed at the farm.[16] On 6 April, Feng Quan was murdered, which the locals justified by claiming he had "promoted French military uniforms and military marches and therefore could not have been a genuine commissioner sent by the Qing".[17]

Compensation of beheaded missionaries

Four French missionaries were killed by the locals, including Henri Mussot (牧守仁) on March 30 or 31, Jean-André Soulié (蘇烈) on April 14, and Pierre-Marie Bourdonnec (蒲德元) as well as Jules Dubernard (余伯南) on July 23.[3] Among them, Soulié was tortured for twelve days before execution.[3] Ten Catholic churches were burned down and a mass of locals converted to Catholicism were killed.[3] A compensation was reached between the Sichuan government's foreign affairs office (四川洋務局), the French consul in Chengdu and Bishop Pierre-Philippe Giraudeau (倪德隆).[18] Sichuan compensated 121,500 silver tael of silver sycees, which would be paid from the tea tax revenues of Dartsedo town, Sichuan.[18]

Punitive campaign

The Qing Chinese responded to the Batang uprising with a punitive campaign. The Sichuan Army under the command of Chinese General Ma Wei-ch'i was said to launch the first retaliations against the Khampas - Chiefs, Lamas and lay people - at Batang, and against the monastery.[19]

The punitive invasion by Han Bannerman General Zhao Erfeng in Kham is well documented, including the German origin of the army's rifles,[20] and he was later called "the Butcher of Kham" for his work. Monks and Khampas were subjected to execution, beheadings, and dousings with fire. The monks at Batang reportedly withstood the invasion until 1906, but afterwards they and the monks from Chatring monastery were all killed, and their monasteries were destroyed.[21] The Prince of Batang was also beheaded for taking part in the uprising.[22]

Monasteries continued to be targeted by Zhao's forces,[23] as did all autonomous polities in Kham as the raids spread and Zhao appointed Qing Chinese officials to positions of authority.[6][24] Zhao's retaliatory invasion in Kham lasted through Qing China's larger invasion of Lhasa in 1910, and on to 1911, when Zhao was killed.[6] Zhao's death[6] was reportedly undertaken by his own men, during the collapse of the Qing dynasty and the rise of Chinese Republican revolutionary forces, around the time of the Xinhai Revolution.

A former Khampa Chushi Gangdruk Tibetan guerrilla named Aten gave his account of the war, where he states the war started in 1903 when the Manchu Qing sent Zhao Erfeng to seize control of Tibetan areas, to control Batang and Litang. Aten recounted Zhao's destruction of Batang, and said Zhao used holy texts as shoeliners for his troops and that "[m]any Tibetans were executed by decapitation or by another typically Chinese method, mass burial while still alive." Aten also called the Manchus "alien conquerors".[25]

Beijing author Tsering Woeser has defended the Tibetans in the Batang uprising, saying that Zhao Erfeng invaded the region to "brutally stop Tibetan protests", while listing the atrocities committed by Zhao.[26]

The Qing military invasion at Batang attempted to change the power structure in the region fundamentally.[27] The historical system of autonomous polities was also attacked, and the region was briefly under Chinese military occupation, until 1911.[28]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Chamdo was in western Kham in Lhasa-controlled Tibet whereas Batang was in eastern Kham under Qing control (as part of Sichuan). Feng Quan felt the need to implement reforms in Batang before reaching Chamdo. The deliberate blurring of the two areas cause by Qing policies eventually led to the formation of an integrated province named Xikang.

- ↑ Both the senior and assistant ambans were normally stationed in Lhasa, but Feng Quan was ordered to station in Chamdo, a town roughly halfway between Lhasa and Sichuan. Xiliang, the Viceroy of Sichuan, argued to the Qing court that "having a senior official stationed in Kham would restore social order, provide better protection for foreign missionaries, and allow merchants and official communications to pass through the region." See Coleman 2014, pp. 213–215

References

- ↑ Coleman 2002, p. 52.

- ↑ Wang 2011, p. 98.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Coleman 2014, p. 247-248.

- 1 2 Coleman 2014, p. 262-263.

- ↑ Scottish Rock Garden Club (1935). George Forrest, V. M. H.: explorer and botanist, who by his discoveries and plants successfully introduced has greatly enriched our gardens. 1873-1932. Printed by Stoddart & Malcolm, ltd. p. 30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jann Ronis, "An Overview of Kham (Eastern Tibet) Historical Polities", The University of Virginia

- ↑ Collection Petits Cerf, Book Review of Françoise Fauconnet-Buzelin's "Martyrs oubliés du Tibet (Les)", Nov 2012

- ↑ Tuttle, Gray (2005). Tibetan Buddhists in the Making of Modern China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0231134460.

- ↑ Prazniak, Roxann (1999). Of Camel Kings and Other Things: Rural Rebels Against Modernity in Late Imperial China. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 147. ISBN 1461639638.

- 1 2 Coleman 2014, p. 93-94, 102.

- ↑ Lamb 1966, p. 186.

- ↑ Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1997). The Snow Lion and the Dragon: China, Tibet, and the Dalai Lama. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 26.

- ↑ Yudru Tsomu, "Taming the Khampas: The Republican Construction of Eastern Tibet" Modern China Journal, Vol. 39, No. 3 (May 2013), pp. 319-344

- ↑ Garri, Irina (2020), "The rise of the Five Hor States of Northern Kham. Religion and politics in the Sino-Tibetan borderlands", Études mongoles et sibériennes, centrasiatiques et tibétaines (51), doi:10.4000/emscat.4631, S2CID 230547448

- ↑ Coleman 2014, p. 207-209.

- ↑ Coleman 2014, p. 231.

- ↑ Coleman 2014, p. 245.

- 1 2 Coleman 2014, p. 257-258.

- ↑ Teichman 1922, p. 21.

- ↑ Pistono, Matteo (2011). In the Shadow of the Buddha: One Man's Journey of Discovery in Tibet. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-47548-5.

- ↑ Wellens, Koen (2010). Religious Revival in the Tibetan Borderlands: The Premi of Southwest China (illustrated ed.). University of Washington Press. pp. 241–2. ISBN 978-0295990699.

- ↑ Woodward, David (2004). Have a Cup of Tibetan Tea. Xulon Press. p. 101. ISBN 1594678006.

- ↑ Schaeffer, Kurtis R.; Kapstein, Matthew; Tuttle, Gray, eds. (2013). Sources of Tibetan Tradition (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. xxxvi. ISBN 978-0231135986.

- ↑ Van Spengen, Wim (2013). Tibetan Border Worlds: A Geohistorical Analysis of Trade and Traders. Routledge. p. 39. ISBN 978-1136173585.

- ↑ Norbu, Jamyang (1986). Warriors of Tibet: the story of Aten, and the Khampas' fight for the freedom of their country. Wisdom Publications. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-86171-050-8.

- ↑ Woeser (September 15, 2011). "The Hero Propagated by Nationalists". High Peaks Pure Earth. High Peaks Pure Earth has translated a blogpost by Woeser written in July 2011 for the Tibetan service of Radio Free Asia and posted on her blog on August 4, 2011. Radio Free Asia. Archived from the original on September 20, 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Coleman, IV, William M. (2014). Making the State on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier: Chinese Expansion and Local Power in Batang, 1842-1939 (PDF) (Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences). Columbia University. pp. 190–260.

- ↑ Goldstein, M.C. (1994). "Change, Conflict and Continuity among a community of nomadic pastoralists—A Case Study from western Tibet, 1950-1990". In Barnett, Robert; Akiner, Shirin (eds.). Resistance and Reform in Tibet. London: Hurst & Co.

This article incorporates text from East India (Tibet): Papers relating to Tibet [and Further papers ...], Issues 2-4, by ((Great Britain. Foreign Office, India. Foreign and Political Dept, India. Governor-General)), a publication from 1904, now in the public domain in the United States.

This article incorporates text from East India (Tibet): Papers relating to Tibet [and Further papers ...], Issues 2-4, by ((Great Britain. Foreign Office, India. Foreign and Political Dept, India. Governor-General)), a publication from 1904, now in the public domain in the United States.

Bibliography

- Bautista, Julius; Lim, Francis Khek Gee (2009), Christianity and the State in Asia: Complicity and Conflict, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-01887-1

- Coleman, William M. (2014), Making the State on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier: Chinese Expansion and Local Power in Batang, 1842-1939 (PDF), Columbia University

- Coleman, William M. (2002), "The Uprising at Batang: Khams and its Significance in Chinese and Tibetan History", in Lawrence Epstein (ed.), Khams Pa Histories: Visions of People, Place and Authority : PIATS 2000 : Tibetan Studies : Proceedings of the Ninth Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Leiden 2000, International Association for Tibetan Studies / BRILL, pp. 31–56, ISBN 90-04-12423-3

- Lamb, Alastair (1966), The McMahon Line: A Study in the Relations Between, India, China and Tibet, 1904 to 1914, Vol. 1: Morley, Minto and Non-Interference in Tibet, Routledge & K. Paul

- Mehra, Parshotam (1974), The McMahon Line and After: A Study of the Triangular Contest on India's North-eastern Frontier Between Britain, China and Tibet, 1904-47, Macmillan, ISBN 9780333157374 – via archive.org

- Singh, Pardaman (1921). Tibet and Her Foreign Relations. University of California.

- Teichman, Eric (1922), Travels of a Consular Officer in Eastern Tibet, Cambridge University Press – via archive.org

- Wang, Xiuyu (2011). China's Last Imperial Frontier: Late Qing Expansion in Sichuan's Tibetan Borderlands. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-6810-3.