Singani is a Bolivian eau-de-vie or brandy distilled from white Muscat of Alexandria grapes. Only produced in the high valleys of Bolivia, it is the country's national distilled spirit and considered part of its cultural patrimony.

Singani has been produced since the 16th century shortly after the Spanish arrived in South America. It was first distilled by monastic orders who needing sacramental wine found it expedient to also distill. Most sources say the name singani derives from a pre-Columbian village of that name near the mission that first distilled the liquor.[1] While its production methods and drinking characteristics more closely resemble eaux-de-vie, it is treated as a brandy for purposes of international trade. It has since been declared a Domain of Origin (Denominación de Origen or DO) and a Geographical Indication (GI) by the Bolivian government.

Since the 1990s, formal Bolivian regulations have codified what has long been practiced, and the vineyards from which singani is made are to be planted at elevations of 1,600 m (5,250 feet) or higher. Singani is thereby known as an altitude product in Bolivian legal terms, the official phrase "of altitude" being also applied to Bolivian wines and grapevine cultivars. Although there are vineyards at elevations much higher than the official minimum, they are difficult to manage, and most production comes from plantations at around 1,800 m (6,000 feet) above sea level close to where the wineries and distillation facilities are located.

Etymology

Linguistic evidence suggests that the word “singani” arises from the native Aymara language word “siwingani”.[2][3] Because the Latin-alphabet representation of Aymara sounds is approximate, this word is alternatively spelled as “sivingani”, “siwinkani”, and similar variants. Sivinga or siwinga is the word for “sedge” (family Cyperaceae), a riparian plant found in Andean valleys protected from weather extremes. The suffix “ni” means “the place of”, which thereby becomes “the place where sedges grow”. With the advent of European settlement, the native word was reduced through syncope (phonetics) to “singani”.[4]

There are various such placenames in Bolivia, historically and today. It is currently not clear which site first became known for producing singani liquor, although there are at least three probable candidates.

The common thread of the etymon is the prehistoric native placename, followed by pre-Columbian settlements of that name at these locations, the founding of missions at those locations, the production of wine, the rise of haciendas with that placename, the production of liquor, and the trading of that liquor into the city of Potosí.

History

Based on genetic studies,[5] two seminal varieties of grape were introduced to the Americas as early as 1520 by Spanish immigrants arriving via the Canary Islands where these varieties were well established, muscat of alexandria and mission (grape). After the former arrived in the Viceroyalty of New Castille (today's Peru and Bolivia), it gave rise to modern varieties such as criolla (grape) and torrontés which are used today in distilled liquors and wine.[5]

Spanish explorers under Francisco Pizzaro reached the Inca empire in 1528. They and accompanying religious orders entered the land far south of Cuzco almost immediately thereafter. By 1538 while Lower Peru was still unsettled due to war, official Spanish cities such as the future archdiocese at Sucre were initiated in Upper Peru or what is today Bolivia.[6] In 1545 a massive silver strike was discovered nearby at the Cerro Rico, Potosi. Because of the importance of this site—nearly all of the silver on the Spanish Main originated from there—special attention from the Spanish Crown and allied missions resulted in the establishment of a greater number of religious settlements in the general area. Within this timeframe the growing mining town of Potosi became the Imperial City of Potosi, at that time one of the largest and richest cities in the world, and by far the largest city in the Americas.[7][8][9] These factors —an unprecedented large city and a profusion of wine-making missions nearby—set the stage for the emergence of singani.

Grapevines were introduced into the mountain valleys of Bolivia by Spanish missionaries arriving as early as 1530, and the production of wine in Bolivia is first known from these places.[3][10] The need for wine was driven by the requirements of the Eucharist liturgy, and wherever there was a mission there would likely be some attempt at winemaking. The date range for the initiation of wine production in Bolivia is from about the 1530s to the 1550s (grapevines take a number of years to mature) which corresponds approximately to the initiation of winemaking in neighboring Peru and Chile. It is generally believed that singani as a name for the distilled spirit arose in that timeframe during the latter half of the 16th Century.[3][10][11]

Most distilled liquor in the Spanish colonies was called aguardiente, many present-day liquor names in the Americas being adopted only by the 17th Century or later.[8][12][13] Three factors would combine to persuade 16th Century Bolivian liquor merchants to label their product: for those who could dominate it, the massively large market and wealth generator of nearby Potosi;[14] the arrival of competing aguardiente products from Lower Peru;[8] and a reliable trade-name—singani—by which their grape liquor could be bought and sold.

The three likely areas where the use of the word singani got its start stretch in an arc from the Potosi to the Spanish royal road connecting Lima and Buenos Aires (partially based on the earlier Inca road system). Sivingani Canton in Mizque Province was an early religious mission center and wine producer in the 1540s.[10] A native settlement called Sivingani lay aside the Uruchini River in the San Lucas municipality of Nor Cinti Province in an area known as the Cintis, and which is believed to have been producing wine and grape-based liquor as early as the 1550s.[3] Another area includes placename settlements in the T'uruchipa Valley,[2] the Vicchoca valley,[3] and Santiago de Cotagaita.[15] Augustinian missions were active in these areas about 1550 and they are among the closest locations to the mining center of Potosi which was the monumental consumer of singani in those days.

After the founding of Potosi in 1545, Spanish settlers traveled from there to the Cintis to give birth, it being too cold and socially turbulent in Potosi.[14] This would create an early connection between this wine region and the imperial city. Subsequently, residents of Potosi who acquired wealth founded villas in the valley of the Cintis. By 1585 this area became the major center of wine and singani production initiating many of the first non-monastic commercial ventures.[10] During the 16th Century, Turuchipa was listed as delivering "vinos endebles" (weak wine) to Potosi, while Cinti delivered wine and distilled liquor.[16] At that time each household in Potosi was observed to possess eight to ten "cántaros" or amphora-like jugs of alcoholic drink.[14] This plus population estimates of 100,000 to 200,000[8] would provide some sense of the overall demand for wine, chicha, and liquor at that time and place.

In the 1600s Bolivia's Tarija region became a supplier of fruit to the singani industry. By the 20th Century Tarija had become the dominant supplier, and wine and singani manufacturers began to consolidate their business there.[10] For example, prominent distiller Kuhlmann moved their operations from the Cinti region to Tarija in 1973 being one of the first to do so.[17] Tarija producers modernized using European equipment and methods and soon displaced other production centers. Today most of Bolivia's grape, wine, and singani industry is centered in Tarija. However, since the year 2000 there has been a resurgence of interest in the original Cinti region, and there are several small producers located there who are reinvigorating early brands.

Over time, as the industry matured, the largest manufacturers of singani settled on a single grape variety for their product, and this plus altitude minimums for vineyards began to be codified in national regulations.

Legal environment

Unlike neighboring pisco which spread itself across two contending countries, singani has always been made only in the territory of Bolivia, and no domain controversy exists as it has for pisco.[18] An exclusive regional product for over 400 years, Bolivia only in recent decades has moved to protect its interests. Part of the motivation was to establish standards so that moonshine could not be called singani. Another impetus was to solidify control of the singani name,[19][20] the unsatisfactory experience of pisco[21][22] and of tequila which can be exported in bulk and bottled under foreign labels being cases in point.[23]

Bolivian Supreme Decree 21948 (1988) declares singani an exclusive and native product of Bolivia, where the word singani cannot be otherwise used, or modified for use, outside of its stated purpose.[24] National Law 1334 of 1992 establishes the domain of origin (DO) classification for singani and the geographical indication (GI), listing specific zones of production.[25] Supreme Decree 24777 (1997) establishes general controls over the DO and prohibited practices.[26] Supreme Decree 25569 (1999) codifies minimum of 1,600 m for altitude wine, and refers to the promotion of altitude singani and wines.[27] Supreme Decree 27113 (2003) describes international enforcement of intellectual property, including the DO and the GI for singani.[28] National Norms NB324001 further defines and controls the process of making singani, it also describes prohibited practices, it spells out the altitude requirement of 1,600 meters for wine, wine products, and cultivars, and sets standards for purity and labeling.[29]

Due to international treaties between the US and other countries, national liquors such as pisco (treaty with Chile), cachaça (treaty with Brazil), and tequila (treaty with Mexico) are listed by the US TTB (Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau) under their own class-type names, and can be used in US commerce so named. No such agreement on type exists with Bolivia and thus singani must be traded in the USA under the nearest existing TTB class which is brandy.[30] Similar to other nations however, Bolivia considers singani not only the national liquor, but a unique product and a cultural patrimony.[3]

The singani area subject to actual production covers about 20,000 acres of mountainous terrain, compared to about 220,000 acres for cognac and 83,000 acres for champagne. Most singani production since about 1980 is concentrated in the Tarija GIs of Arce, Avilés, and Méndez.

Agencies involved in the control and oversight of singani are IBNORCA a publisher of regulations, SENASAG an enforcer of regulations, and CENAVIT a national laboratory and investigation arm. FAUTAPO is an internationally funded source of study, education, promotion, and development of the grape, wine, and singani industry in Bolivia.

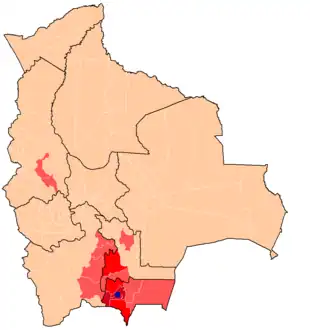

Geographic zones

The legally defined zones for the vineyards and distilleries that produce singani include Provinces in four of the nine Departments of Bolivia. Not all areas of these provinces are suitable for viticulture. In the La Paz provinces the land is steeply vertical and the weather is semi-tropical. In the Potosi provinces the land is very high (over 13,000 feet), cold, windswept and arid. Such conditions limit vineyards to small municipalities and cantons within the provincial areas as listed by Law 1334. Where municipalities of Bolivia establishes the “Certificate of Origin” that accompanies singani, determines the 1,600 meter (5,250 feet) elevation above sea level minimumor cantons of Bolivia are not listed, larger areas of the Province may be suitable for viticulture, otherwise, only the local cantons and municipalities are suitable.

The zones of production for GI Singani are: La Paz Department (Bolivia), Loayza Province and Pedro Domingo Murillo Province, Cantons and Municipalities Luribay and Sapahaqui. Chuquisaca Department, Nor Cinti Province and Sud Cinti Province. Tarija Department, José María Avilés Province, Eustaquio Méndez Province, and Aniceto Arce Province. Potosi Department, Nor Chichas Province, Sud Chichas Province, Cornelio Saavedra Province, and José María Linares Province, with Cantons and Municipalities Turuchipa, Cotagaita, Vicchoca, Tumusla, Poco Poco, Tirquibuco, and Oroncota.

Production

Of all the grape varieties shipped to the new world by Spanish immigrants, the variety vitis vinifera muscat of alexandria was most prized for its intense aroma. This variety and muscat frontignan (muscat blanc à petits grains) are considered to have among the strongest aromatic terpenol profiles of any wine-making grapes, especially when grown in more suited conditions of terroir.[31]

Qualities and terroir

The grapes for singani are produced in the Andes mountains at elevations from 5,250 up to 9,200 feet above sea level. For example, the vineyards at San Juan del Oro in Tarija are at 8,850 feet amsl.[17] The largest vineyards are located at around 6,000 feet, however, due to logistical difficulties at higher elevations. Given the proximity to the equator, thermoclines are higher, with a lower probability of freezing even on winter nights. The structure of surrounding mountain peaks protects growing regions from seasonal cold fronts (surazos) and hailstorms that can damage plants. Mountain air tends to be thin, cold and dry, yet solar radiation is stronger, passing through both warming radiation and intense ultraviolet light. Due to the fact that mountain air cannot hold heat well, grapevines experience dramatic daily air temperature fluctuations. Studies of altitude vineyards by CENAVIT and other organizations suggest that fruit subject to these conditions tends to produce greater concentrations of monoterpene aromatics held in a free state rather than sequestered as oils.[17][32] This is important as oils do not survive the distillation process. The soil is fluvial erosion from surrounding peaks, well structured deep clay and sandy loam with good pitch and permeability.[17] Water is derived from snow melt and mountain rain directly from the adjacent peaks of Iscayachi.[17] Because land in the mountains is mostly vertical, acreage for singani tends to be microclimate mini-plots, one of the reasons hand-cultivation is preferred over difficult-to-deploy agricultural machinery.

Unlike other vinous spirits, nomenclature singani is made only from the Alexandria varietal and is single batch, never blended.[29] Because of singani producers’ methods learned over centuries, the extreme climate at high altitude, the mountain soil and other factors of terroir, singani has a distinct flavor profile. The profile is achieved without barrel aging, much like tequila. The coded regulatory organoleptic properties of singani are, aspect: clear, clean, brilliant; color: colorless; aroma: terpenol profile of alexandria muscat predominates (primarily geraniol, linalool, and nerol);[33] taste (mouthfeel): fine, soft, smooth, with balanced structure.[34]

Singani does not contain sulfites, colorants, marc or lees, flavor enhancers or other additives which may be present in other spirits like brandy.[30][34] Given this, and the lack of aging, and because of similar production techniques, singani resembles eau-de-vie much more than it does brandy. Bolivian regulations have further tightened in recent years and singani is held to significantly stricter standards of chemical purity than what may be allowed in other countries. For example, singani must assay at less than 0.6 mg/L ionic copper whereas many countries that have standards allow 2 to 10 mg/L copper in their liquor products.[29][34][35][36]

Fermentation and distillation

Grapevines are tended year round, but the fruit is harvested only once a year. Clusters of berries are “groomed” by hand before picking so that only berries that meet published standards are collected.[34] Fermentation produces a “must” or raw wine which is held for distillation. Distillation today uses European batch stills and stainless holding tanks to maintain quality. Stills must not introduce insoluble solids or suspended cellulose as when heated they release odors and affect the aromatic quality of Singani.[17] The stills are also run cold and cut off early to deliver Singani's character.[34] The goal of fermentation is to retain and enhance the characteristic terpenol profile. The goal of distillation is to capture the aromatics while removing nearly all fusel oil. The resulting profile must be just right because barrel aging or blending cannot be used to alter it. Distilled liquor is held for precisely 6 months in clean neutral vessels before bottling so as to allow the aroma profile to intensify.

Aging

Much of the profile of aged liquor comes from ethanol interacting with wood which produces vanillins and other co-generated compounds.[37] In singani, all of the aromatic profile must come from the grape itself as it interacts with yeast during the fermentation process. A grape richer in desirable aromatics is therefore preferable to thin, acidic varieties as may be used for cognac. Producers who have experimentally aged singani have reported that singani's distinctive character becomes diminished, and the resultant brown liquor tastes more like other brown liquors than singani. Given current national standards, such a liquor could not rightfully be called singani.

Congeners

As is true for nearly all liquors produced for human consumption, singani comes off the still at a higher proof than it is bottled. This is done to reduce if not eliminate the level of fusel oil. Singani manufacturers take care to keep undesirable substances out of the product so that the characteristic terpenol profile dominates and is not blemished by off-odors such as grassiness (amyl alcohol), pineapple (ethyl butyrate), and other congeners.[34]

Occasional public reports stating that singani and its cousin pisco are a “fiery brandy” that makes a “potent cocktail” are probably referring to local moonshine.[38] Fiery tastes are due to fusel oils and other contaminants characteristic of raw unregulated liquor. Singani has no detectable fusel and actually must taste smooth according to its legal profile.[34] As far as potency goes, singani is bottled at 80 proof and has the same ethanol content as most other liquors on the market.

Producers and brands

There are 3 major singani manufacturers, several medium producers, and a host of small operations. Only the three majors have the reach to supply the entire country, medium suppliers typically cover a particular region, and small firms specialize in very local markets.

SAIV is a large agro-industrial conglomerate with multiple interests and produces Bolivia's Casa Real brand. Family-owned Bodegas Kuhlmann distills two lines of singani, Los Parrales and Tres Estrellas. A publicly traded company, La Concepción, produces the Rujero brand. Together, these three account for most consumption of singani.

Medium level producers are SAGIC with the San Pedro de Oro brand, the Sociedad San Rafael with the Sausini brand, Bodegas Kohlberg with the La Cabana brand, Casa de Plata with the Valluno brand, and singani Ocho Estrellas.

Many Bolivian producers tier their brands with colors, black, red, blue, to reach different markets, much the way whisky producer Johnnie Walker does. In 2004, 4 million bottles of singani were produced by the industry.[17] The amount of production is constrained by the size of the market and by the amount of acreage under cultivation, and is ultimately constrained by the amount of suitable land within the domain. By the year 2010 total acreage in vineyards was between 12,000 and 13,000 acres which includes all uses of grapes, table, wine, and singani.

International awards

Beginning in the year 2005, singani producers, notably Bodegas Kuhlmann, have made a concerted effort to enter international competition. The industry has focused on professional non-commercial contests such as the Concours Mondial de Bruxelles[39] and those sponsored by the French Oenologists Union.[40] Nine gold and grand gold medals have been awarded at the international level in seven consecutive years to this small industry.

Use

Since its inception in the mid- to late 1500s, singani has been often drunk as is, cocktail culture only being introduced in the 19th Century. However, around the year 1608, in the cold environment of mines located above 14,000 feet, Potosi miners mixed hot milk with singani and spices and called it sucumbé, a name of possible African origin, and the oldest singani mixed drink known.

Sometime in the 1800s railroad engineers from Britain and America began to lay down track in the Andes nations including Bolivia. A 19th century favorite back home in Britain was “gin on gin” or gin with alcoholic ginger beer. Unable to get either one in-country, British expatriates improvised with singani and whatever bubbly came to hand. The railroad term “shoofly” (perhaps from “short fly”) refers to a short length of track built as a temporary expedient to the main line and is slang for “workaround”.[41][42] Singani and bubbly beverage was thus dubbed a “shoofly”.[43] Being unpronounceable to locals it emerged as “chuflay”, which is still the favorite cocktail based on singani. Other traditional mixes are the “yungueño”, tumbo (banana passionfruit) cocktail, and “té con té”, which signifies "tea with trago", that is, hot tea with "trago" (an alcoholic drink), either singani or straight cane alcohol. This proto "mixed drink" was an essential part of the long trips in the mountains in unheated buses, and still has its fans even in the tropical parts of Bolivia.

Singani is wildly popular at national festivals, most notably Saint John's Eve and the annual Virgen del Socavón carnival (Carnaval de Oruro). Singani is also the traditional drink at weddings, religious holidays, birthday parties, and other celebrations. A common pastime is to play “cacho”, a cup and dice game similar to yahtzee or generala, while drinking singani either as a penalty or reward depending on the players’ mood.

References

- ↑ "Los Cintis reivindican el origen del singani de la mano de una ley". www.paginasiete.bo (in Spanish). Retrieved 2022-01-24.

- 1 2 Rivadereira Prada, D. Raul (2010). Diccionario de americanismos (PDF) (in Spanish). XV Feria Internacional del Libro. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cardona G., Guillermo W. (May 2012). "Origenes e historia del nombre singani" (PDF). Epoca Ecologica (in Spanish). FUNDESUBO. 2 (21). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2013.

- ↑ "Bolivianismos: Muestra de bolivianismos incorporados en el Diccionario". FMBolivia (in Spanish). May 2011. Archived from the original on 24 March 2013.

- 1 2 Alejandra Milla Tapia; José Antonio Cabezas; Felix Cabello; Thierry Lacombe; José Miguel Martínez-Zapater; Patricio Hinrichsen & María Teresa Cervera (June 2007). "Determining the Spanish Origin of Representative Ancient American Grapevine Varieties". American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 58 (2 242–251). ISSN 0002-9254.

- ↑ "The Hierarchy of the Catholic Church".

- ↑ Demos, John (July 2003). "The high place: Potosi". Common-Place, the Interactive Journal of Early American Life. 3 (4). Archived from the original on 14 November 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Lacoste, Pablo (2004). "La vid y el vino en América del Sur: el desplazamiento de los polos vitivinícolas (siglos XVI al XX)". Universum (Talca) (in Spanish). Talca: Revista Universum. 12 (2). ISSN 0718-2376.

- ↑ Ricardo Brizuela (April 2009). "Pisco vs. pisco, y que hay con el singani?". Diario del Vino (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 30 April 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Canedo Daroca, Marcela (2008). Wines of Bolivia from the highest vineyards in the world. Fundación FAUTAPO Educación para el Desarollo. ISBN 978-99905-960-4-5.

- ↑ "El Singani D.O. y su historia" (in Spanish). Cepas de Altura. 2007. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014.

- ↑ "History of Tequila". El Perdido Tequila. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013.

- ↑ Ayala, Luis K (2010). The rum experience. Rum Runner Press Inc. ISBN 978-0970593801.

- 1 2 3 Bartolome Arzans Orsua y Vela. Lewis Hanke; Gunnar Mendoza (eds.). Historia de la Villa Imperial de Potosi (in Spanish). Brown University Press 1965. Archived from the original on 2013-05-25.

detail search, by title

- ↑ Ramon Rocha (August 2006). "Sobre el origen del singani" (in Spanish). Trancapechoboliviano. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014.

- ↑ Serrano, Carlos (2008). "Sobre las rutas comerciales y el patrimonio minero" (PDF). De Re Metallica (in Spanish). Sociedad Espanola para la defensa del patrimonio geologico y minero. 10–11. ISSN 1577-9033.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ivan Blushe Sagarnaga (2005). Diego Bigongiari (ed.). South American Vineyards, Wineries and Wines. Austral Spectator. ISBN 9872091412.

- ↑ Liralg. "Controversia sobre el origen del pisco" (in Spanish). Centro de Negocio de la Pontífica Universidad Católica del Perú. Archived from the original on 31 May 2012.

item 4671

- ↑ "Singani Peru". Brands of the World. 2011. Archived from the original on 2 January 2012.

- ↑ "Singani Argentina". Sagic Argentina. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013.

- ↑ "Pisco liquer dispute between Chile and Peru". Trade and Environment Database (TED). Case number: 145: American University, WDC.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ↑ Ricardo Brizuela (August 2012). "Ahora si se complica el comprender de quien es el pisco". Diario del Vino (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 30 April 2009.

- ↑ "Trade in Tequila Agreement". International Trade Division, US Department of the Treasury. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ↑ "Decreto Supremo 21948". Gaceta Oficial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia (in Spanish). 1551. Archived from the original on 2015-04-04.

- ↑ "National Congress of Bolivia. Ley No. 1334 de 4 de mayo de 1992 sobre las Denominaciones de Origen, Indicaciones geográficas (Productos Vitícolas y "Singani")". WIPO/OMPI CLEA.

- ↑ "Decreto Supremo 24777". Gaceta Oficial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia (in Spanish). 2023. Archived from the original on 2015-04-04.

- ↑ "Decreto Supremo 25569". Gaceta Oficial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia (in Spanish). 2179. Archived from the original on 2012-05-29.

- ↑ "Decreto Supremo 27113". Gaceta Oficial del Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia (in Spanish). 2506. Archived from the original on 2012-05-06.

- 1 2 3 "Normas Bolivianas NB324001" (PDF). IBNORCA.

- 1 2 "US TTB Title 27, Part 5.22(d)". US Department of the Treasury. Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau.

- ↑ The Forum Œnologie Association. "Muscats du monde". OenoPlurimedia. Archived from the original on 26 November 2012.

- ↑ Javier Gonzales Iwanciw & Pablo Suarez (March 2007). Giles Stacey (ed.). Poverty Reduction at Risk in Bolivia (PDF). Netherlands Climate Assistance Programme.

- ↑ Marais, J. (1983). Terpenes in the aroma of grapes and wines: a review (PDF). Viticultural and Oenological Research Institute of South Africa.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Victor Ricardo Moravek Delfin, ed. (2010). Elaboracion de singani (in Spanish) (1ra ed.). Fundacion FAUTAPO.

Deposito Legal 4-1-2941-10

- ↑ Ignacio Orriols (2006). Elaboracion de Aguardientes (PDF) (in Spanish). Sergude. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2012.

- ↑ Anon (2009). Marchio di qualità con indicazione di origine (PDF) (in Italian). Disciplinare per il settore Grappa. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 April 2015.

- ↑ Andrew G.H. Lea; John R. Piggot, eds. (2003). Fermented beverage production (Second ed.). Kluwer Academic Plenum. ISBN 0-306-47275-9.

- ↑ A.D. Hans Soria O. (2012). "Dificultades no frenan avance de vitivinicultura". Los Tiempos (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 13 November 2012.

- ↑ "Concours Mondial de Bruxells".

- ↑ "Vinalies Internationales".

- ↑ "Trains glossary of common railroading terms". Trains Magazine. Kalmbach Publishing. Archived from the original on 20 January 2013.

- ↑ Director, Bureau of Railroads and Harbors, ed. (2008). "FDM-17-40-35.3" (PDF). Facilities Development Manual. State of Wisconsin Department of Transportation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2015.

- ↑ Nicolas Fernández Naranjo & Dora Gómez de Fernández (1967). El diccionario de bolivianismos (in Spanish). Los Amigos del Libro. ISBN 8478006117.

Further reading

- Canedo Daroca, Marcela (2008). Wines of Bolivia from the highest vineyards in the world. Fundación FAUTAPO Educación para el Desarollo. ISBN 978-99905-960-4-5

- Sagarnaga, Ivan Blushe (2005). Diego Bigongiari. ed. South American Vineyards, Wineries and Wines. Austral Spectator. ISBN 9872091412.

- Lougheed, Vivian and John Harris (2006). Bolivia. Walpole, MA; Hunter Publishing.