John Gladstone | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of Parliament for Lancaster | |

| In office 1818–1820 | |

| Preceded by | John Fenton-Cawthorne |

| Succeeded by | John Fenton-Cawthorne |

| Member of Parliament for Woodstock | |

| In office 1820–1826 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Henry Dashwood |

| Succeeded by | Marquess of Blandford |

| Member of Parliament for Berwick-upon-Tweed | |

| In office 1826–1827 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Francis Blake |

| Succeeded by | Sir Francis Blake |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Gladstones 11 December 1764 Leith, Midlothian |

| Died | 7 December 1851 (aged 86) Fasque House, Kincardineshire |

| Resting place | St. Andrew's Chapel, Kincardineshire |

| Political party | Tory |

| Spouse(s) | Jane Hall (m. 1792–1798) Anne MacKenzie Robertson (m. 1801–1835) |

| Children | |

| Parents |

|

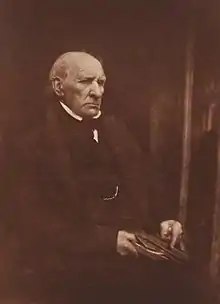

Sir John Gladstone, 1st Baronet, FRSE (11 December 1764 – 7 December 1851) was a Scottish merchant, slave owner, and Tory politician best known for being the father of British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone.

Born in Leith, Midlothian, through his commercial activities he acquired ownership over several slave plantations in the British colonies of Jamaica and Demerara-Essequibo; the Demerara rebellion of 1823, one of the most significant slave rebellions in the British Empire, was started on one of Gladstone's plantations. The extent of his ownership of slaves was such that after slavery was abolished, by the passage of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 by the Parliament of the United Kingdom, he received the largest of all compensated emancipation payments made via the Slave Compensation Act 1837.

Gladstone then proceeded to expel the majority of the newly emancipated African freedmen from his plantations and imported large numbers of Indian indentured-labourers to his plantations, through false promises of providing them schools and medical attention. However, upon arrival they were paid no wages, the repayment of their debts being deemed sufficient, and worked under conditions that continued to resemble slavery in everything except name .

During this period, he sat in Parliament from 1818 to 1827. Dying in 1851, Gladstone's involvement in slavery heavily influenced the proslavery thought of his son during his early political career.

Early life

Born John Gladstones on King Street in Leith north of Edinburgh, John Gladstones was the eldest son of the merchant Thomas Gladstones, and his wife, Helen Neilson. They lived on Coalhill, at the south end of the Shore, Leith. John was the second of the family's sixteen children. John Gladstones left school in 1777 at the age of 13, later describing his education as "a very plain one – to read English, a little Latin, writing and figures comprehending the whole."[1] John was apprenticed to Alexander Ogilvy, manager of the Edinburgh Roperie and Sailcloth Company ropeworks in Leith. On completing his apprenticeship in 1781, he entered his father's corn and flour trading and provisioning business.[2]

Thomas Gladstones was aware of the limitations of Leith, especially compared with the opportunities then opening up in Glasgow and in Liverpool. In 1784, he sent John to the German Baltic ports to buy grain, transacting his business through an interpreter. In 1786, he travelled to Liverpool, Manchester and London to sell his father's corn and sulphuric acid.[3] But the following year, with his father's financial support, John Gladstones was determined to move to Liverpool. Once he had settled in Liverpool, Gladstones dropped the final "s" from his surname (although this was not formally changed by royal licence until 1835).[4][5] Almost immediately he went into partnership with grain merchants Edgar Corrie and Jackson Bradshaw. The business of Corrie, Gladstone & Bradshaw, and the wealth of its members, soon grew very large.[6] John Gladstone spent a year in the United States, travelling to New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia and Maryland to purchase wheat, maize, flax-seed, hemp, tobacco, timber, leather, turpentine and tar.[7]

From 1835, under royal licence, he officially dropped the "s" at the end of his name.[8]

John Gladstone lived on Bold Street from the time he moved to Liverpool until after his first marriage in 1790 to Jane Hall, daughter of a lesser Liverpool merchant. John never travelled abroad again: but the new couple settled into Rodney Street. Jane had no children, and their marriage lasted barely six years. Although he was a devout Presbyterian, there was no Scottish church in Liverpool and Gladstone and the other Scots resident in Liverpool worshipped at Renshaw Street Unitarian Chapel. In 1792, Gladstone, William Ewart and some other Scots built a Scottish chapel on Oldham Street and the Caledonian School opposite it for the education of their children. Gladstone also had a new home built for himself at 62 Rodney Street, Liverpool, at the cost of £1,570 (equivalent of £229,320 in 2019). It was finished in September 1793.[9]

Marriage and family

In 1792, John Gladstone married Jane Hall (1765–1798), the daughter of Joseph Hall, a Liverpool merchant. Her health was never good and she died in 1798.

On 29 April 1800, he married Anne Mackenzie Robertson (1772–1835) at St Peter's Parish Church in Liverpool. She was the daughter of Andrew Robertson, a solicitor and Justice of the Peace and the Provost of Dingwall in Ross-shire.[10] They had six children together:

- Anne Mackenzie Gladstone (1802–1829)

- Sir Thomas Gladstone, 2nd Baronet (1804–1889)

- Robertson Gladstone (1805–1875)

- John Neilson Gladstone (1807–1863)

- William Ewart Gladstone (1809–1898)

- Helen Jane Gladstone (1814–1880)[11]

Around 1804, John Gladstone ceased to attend the Presbyterian church, attending the Church of England St Mark's Church from then on with his family. The Church of Scotland had also never been to Mrs Gladstone's liking because of the Episcopalian tradition of the Robertson family and her own strong evangelicalism.[12] Gladstone decided that he wanted to move his young family away from the city centre, and in 1813 the Gladstone family finally settled at Seaforth House, two years after construction had begun. A mansion on 100 acres (0.40 km2) of Litherland marsh, four miles (6 km) north-northwest of Liverpool, the Seaforth estate combined the mansion, a home farm and a village of cottages, and here John Gladstone could live as a landed gentleman. In 1815 he built St Thomas's Anglican Church at Seaforth, the rector of which, the Reverend William Rawson, established a school in the parsonage for educating the sons of local gentlemen, including the Gladstone boys. He also built St Andrew's Episcopal Church in Renshaw Street, with a school attached to it for educating poor children.[13]

Business

After sixteen years of operations, the partnership of Corrie, Gladstone & Bradshaw was dissolved in 1801 and its business was continued by John Gladstone under the name of John Gladstone & Company. He took his brother Robert into partnership with him in 1801, and eventually all six of his brothers moved to Liverpool to work in various mercantile businesses. John Gladstone's business became very extensive, having a large trade with Russia, and as sugar importers and West India merchants. In 1814, when the monopoly of the British East India Company was broken and trade with India was opened to competition, Gladstone's firm was the first to send a private ship (Kingsmill), from Liverpool to Calcutta.[lower-alpha 1] He also invested in property, constructing a number of houses in Liverpool and purchasing an estate just outside the city. He made a fortune trading in corn with the United States and cotton with Brazil.

Slave owner

Gladstone acquired large sugar plantations in Jamaica and Demerara, and was Chairman of the West India Association. The Demerara Rebellion of 1823, a massive slave revolt, happened on his plantation in the colony of Demerara-Essequibo (in present-day Guyana) and was brutally crushed by the army and militia.[15] The leader of the Demerara revolt of 1823 was Jack Gladstone, an enslaved man who worked as a cooper on the "Success" plantation, owned by John Gladstone. He was named Gladstone in accordance with the convention of the enslaved taking the surnames of their masters.

With help from his son William, Gladstone was awarded a payment as a slave owner in the aftermath of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833 with the Slave Compensation Act 1837.[16][17][18] Gladstone's claim was the single largest of any recipient made by the Slave Compensation Commission and he had the largest number of slaves.[19][20] His fellow Lowland Scot, James Blair made the single biggest claim for one plantation, but Gladstone's claims were spread out over multiple plantations and were worth far more. Gladstone was associated with eleven different claims. He owned 2,508 slaves in British Guiana and Jamaica and received a £106,769 payment (equivalent to £10,320,000 in 2021).[18]

After the abolition of slavery, John Gladstone sought indentured labourers from India to work in his sugar plantations. Knowing that a number of Indians had been sent to the island of Mauritius, a British colony in the Indian Ocean, as indentured labour,[21] Gladstone expressed a desire to obtain indentured labour from India for his plantations in the West Indies in a letter dated 4 January 1836 to Messrs Gillanders, Arbuthnot & Co. of Calcutta.[22] The conditions imposed on these indentured labourers were so appalling that they fled in numbers and the 'experiment' was abandoned by Gladstone.[23] Whilst trying to recruit indentured labourers, he wrote that the work in the sugar plantations was light and conditions generally good, including schools and medical attention.[24] This was a picture he had derived from information given by plantation managers, who did not communicate the routine abuse of slaves nor their miserable conditions of malnutrition, overcrowding, and overwork. It ignored the comprehensive and damning evidence on the reality of slavery in the British and French Caribbean, provided by many writers of the time such as missionaries and other returning Britons.[23] The appalling reality of lives on the Gladstone owned plantations in Demerara is well documented.[23]

Politics

Gladstone was also interested in politics. At first he had been a Whig, but from 1812 onwards his political outlook appears to have changed due to a number of factors. In religion he had long ceased to have any sympathy with Unitarianism or Presbyterianism. He had become alienated from the Whig and Radical circles in Liverpool, and feared the disorder caused by the Napoleonic Wars.[25] The friendships he formed with Tories George Canning and Kirkman Finlay also had a great influence on his changing political outlook, and he became a Tory. In 1812 he presided over a meeting at Liverpool which was called to invite George Canning to represent Liverpool in the House of Commons.[26]

In 1817 John Gladstone decided to enter parliament. Although he wanted to stand for election in Liverpool, there was no vacancy, and he was obliged to explore other possibilities, including Ross-shire and Stafford, before deciding to stand for Lancaster in the general election of 1818.[27] At the general election of 1818, Gladstone chose to stand for Woodstock, due to the heavy financial cost of the Lancaster constituency.[28] He made few speeches in the House of Commons, but he was regarded as having done good work in committees and was known as one of the most informed MPs when it came to commerce. He was in favour of a qualified reform of the franchise and of Greek independence during the 1820s.[29]

When George Canning left his Liverpool seat in 1822, Gladstone sought to be elected as his successor. However, William Huskisson was chosen instead, and this rejection by Liverpool soured Gladstone's relationship with the city.[30] In 1826, he was elected as the second MP for Berwick-upon-Tweed in a hard-fought contest which he won by only six votes. In the following year, disgruntled supporters in Berwick, who had expected to profit from his election, brought an election petition against him alleging bribery, treating and accepting illegal votes. The election committee upheld their complaints and he was unseated on 19 March 1827.[31]

At the 1837 general election he sought to return to parliament when he contested the Dundee seat, but he was easily defeated by the constituency's incumbent Whig MP Sir Henry Brook Parnell who won 663 votes to Gladstone's 381.[32]

Later life

In around 1820 John Gladstone began searching for an estate in his native Scotland, and in December 1829 he purchased the Fasque Estate in Kincardineshire from Sir Alexander Ramsay for £80,000 (equivalent to £8,848,932 in 2019). He decided to return, with his family, to Scotland. Only Robertson would remain in Liverpool to look after the business.[33] In a sense the decision to leave Liverpool was easy, with the family attachment to Liverpool and Seaforth now much weakened following the death of Gladstone's eldest child, Anne, in 1829. Mrs Gladstone had never made any real connection with Liverpool, because of her shyness, her frequent illnesses and her involvement with her children.[33] Gladstone and his family left Seaforth in 1830, spending the next few years living in Royal Leamington Spa and Torquay seeking health for Mrs Gladstone and their daughter, Helen, before taking up residence at Fasque House in the summer of 1833.[34] The family spent their winters in Edinburgh at their townhouse at 11 Atholl Crescent[35]

In 1838, using the wealth he had amassed from his plantations and other business ventures, John Gladstone paid for several philanthropic works in his original home town of Leith, including St Thomas's Church, an adjacent manse, a free school for boys, a free school for girls, a "house for female incurables", and a public rose garden. In 1846 Gladstone was created a baronet by the outgoing Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel.[36]

Sir John Gladstone, 1st Baronet, of Fasque and Balfour in the County of Kincardine, died at Fasque House in December 1851, 4 days shy of his 87th birthday, and was buried at St Andrew's Episcopal Church at Fasque. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Sir Thomas Gladstone, 2nd Baronet. He has been described by Checkland as "a strong, vigorous and overpowering man, whose life was strewn with quarrels, great and small."[37]

Memorials

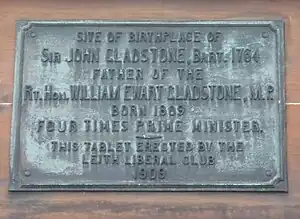

A plaque was erected in 1909 at the corner of Great Junction Street and King Street in Leith commemorating the site of the birthplace of John Gladstone.

Gladstone Place on Leith Links is named in his honour as is "Gladstones" public house on Mill Lane in Leith.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Other vessels trading with India in which he had an ownership interest included: Roscoe, Duke of Lancaster, Seaforth, Theodosia, Richard, Bencoolen, and Westmoreland.[14]

Citations

- ↑ Sydney Checkland, The Gladstones: A Family Biography, 1764–1851 (Cambridge University Press, 1971), pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Checkland 1971, p. 11.

- ↑ Checkland 1971, p. 13.

- ↑ Phillimore, William Phillimore Watts; Fry, Edward Alexander (1905). An Index to Changes of Name : Under Authority of Act of Parliament or Royal License, and Including Irregular Changes from I George III to 64 Victoria, 1760 to 1901 (PDF). Phillimore & Co. p. 129. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ↑ Mosley, Charles, ed. (2003). Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knighthood (107 ed.). Burke's Peerage & Gentry. p. 1557. ISBN 0-9711966-2-1.

- ↑ Checkland 1971, p. 14.

- ↑ Checkland 1971, p. 24.

- ↑ Cassell's Old and New Edinburgh; vol. 6, p. 250

- ↑ Checkland 1971, pp. 31, 33.

- ↑ ThePeerage.com: Anne MacKenzie Robertson

- ↑ https://iow-chs.org/island-people/helen-jane-gladstone-1814-80/

- ↑ Checkland 1971, p. 46.

- ↑ Checkland 1971, p. 79.

- ↑ Checkland (1954), p. 218.

- ↑ Michael Craton, "Proto-peasant revolts? The late slave rebellions in the British West Indies 1816-1832." Past & Present 85 (1979): 99-125 online.

- ↑ "John Gladstone: Profile & Legacies Summary". Legacies of British Slave-ownership. UCL Department of History 2014. 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- ↑ Roland Quinault, "Gladstone and slavery." Historical Journal 52.2 (2009) 369.

- 1 2 "John Gladstone". Legacies of British Slave-ownership. University College London. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ↑ Manning, Sanchez (24 February 2013). "Britain's colonial shame: Slave-owners given huge payouts after abolition". Independent on Sunday. London. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ↑ "Britain's Forgotten Slave Owners". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ↑ History of the South Asian Diaspora. wesleyan.edu

- ↑ "Copy of letter from John Gladstone, Esq. to Messrs. Gillanders, Arbuthnot & Co". 4 January 1836. Archived from the original on 28 December 2007. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- 1 2 3 Sheridan, Richard B. (2002). "The Condition of slaves on the sugar plantations of Sir John Gladstone in the colony of Demerara 1812 to 1849". New West Indian Guide. 76 (3/4): 243–269. doi:10.1163/13822373-90002536. hdl:1808/21075.

- ↑ Letter from John Gladstone, Esq. to Messrs. Gillanders, Arbuthnot & Co., Liverpool, 4 January 1836. http://www.indiana.edu/~librcsd/etext/scoble/JANU1836.HTM accessed 24 November 2015

- ↑ Checkland 1971, p. 51.

- ↑ Checkland 1971, p. 61.

- ↑ Checkland 1971, p. 102.

- ↑ Checkland 1971, p. 104.

- ↑ Checkland 1971, p. 106.

- ↑ Checkland 1971, p. 162.

- ↑ Fisher, David R. "Gladstone, John (1764-1851), of 62 Rodney Street, Liverpool; Seaforth House, Lancs. and 5 Grafton Street, Mdx". www.historyofparliamentonline.org. The History of Parliament Trust. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ↑ Hazel, John W. (1977). John W Hazel's Book of Records. Dundee: D. Winter & Son Ltd. p. 46.

- 1 2 Checkland 1971, p. 222.

- ↑ Checkland 1971, pp. 227, 238.

- ↑ Checkland 1971, p. 282.

- ↑ "No. 20618". The London Gazette. 30 June 1846. p. 2391.

- ↑ Checkland 1971 , p. 311.

References

- Burnard, Trevor, and Kit Candlin. "Sir John Gladstone and the debate over the amelioration of slavery in the British West Indies in the 1820s." Journal of British Studies 57.4 (2018): 760–782.

- Checkland, S. G. (1954). "John Gladstone as Trader and Planter". The Economic History Review. 7, New Series (2): 216–229. doi:10.2307/2591623. JSTOR 2591623.

- Checkland, S. G. (1971). The Gladstones: A Family Biography 1764-1851. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-07966-7.

- Jenkins, Roy (1996). Gladstone. London. pp. 4–11, 14–8, 28, 73, 78–9, 89, 96, 177–9, 432n, 627. ISBN 0-333-66209-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Quinault, Roland. "Gladstone and slavery." The Historical Journal 52.2 (2009): 363–383. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X0900750X focus on father and son

- Shannon, Richard (1984). Gladstone: Volume I 1809 - 1865. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-1591-8.

- Sheridan, Richard B. "The condition of the slaves on the sugar plantations of Sir John Gladstone in the colony of Demerara, 1812-49." New West Indian Guide/Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 76.3-4 (2002): 243-269 online.

- Taylor, Michael. "The British West India interest and its allies, 1823–1833." English Historical Review 133.565 (2018): 1478–1511. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/cey336, focus on slavery

- Gladstone, John. The Correspondence Between John Gladstone, Esq., MP, and James Cropper, Esq., on the Present State of Slavery in the British West Indies and in the United States of America: And on the Importation of Sugar from the British Settlements in India: with an Appendix; Containing Several Papers on the Subject of Slavery. (West India Association, 1824)., a primary source. online