| Slieve Gullion | |

|---|---|

| Sliabh gCuillinn | |

Slieve Gullion from Aughanduff | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 573 m (1,880 ft) |

| Prominence | 478 m (1,568 ft)[1] |

| Listing | County top (Armagh), Marilyn |

| Coordinates | 54°08′N 6°26′W / 54.133°N 6.433°W |

| Naming | |

| English translation | mountain of the steep slope |

| Language of name | Irish |

| Geography | |

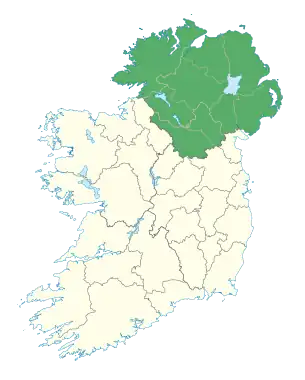

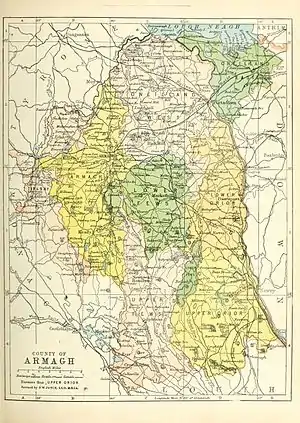

Slieve Gullion Location in Northern Ireland  Slieve Gullion Slieve Gullion (island of Ireland)  Slieve Gullion Slieve Gullion (the United Kingdom) | |

| Location | County Armagh, Northern Ireland |

| Parent range | Ring of Gullion |

| OSI/OSNI grid | J024201 |

Slieve Gullion (from Irish Sliabh gCuillinn, meaning 'hill of the steep slope'[2] or Sliabh Cuilinn, "Culann's mountain")[3] is a mountain in the south of County Armagh, Northern Ireland. The mountain is the heart of the Ring of Gullion and is the highest point in the county, with an elevation of 573 metres (1,880 ft). At the summit is a small lake and two ancient burial cairns, one of which is the highest surviving passage grave in Ireland. Slieve Gullion appears in Irish mythology, where it is associated with the Cailleach and the heroes Fionn mac Cumhaill and Cú Chulainn. It dominates the countryside around it, offering views as far away as Antrim, Dublin Bay and Wicklow on a clear day.[4] Slieve Gullion Forest Park is on its eastern slope.

Villages around Slieve Gullion include Meigh, Drumintee, Forkhill, Mullaghbawn and Lislea. The mountain gives its name to the surrounding countryside, and is the name of an electoral area within Newry, Mourne and Down District Council.

Geography

Slieve Gullion is a steep-sided mountain with a flat top and a height of 573 metres (1,880 ft). It is the eroded remains of a Paleocene volcanic complex. It is surrounded by a ring dike known as the Ring of Gullion, a designated Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). Slieve Gullion has been shaped by glaciation and exhibits a classic 'crag and tail' glacial feature. The 'tail', made up of glacial deposits, points south, ending at Drumintee. The geological formation was the first ring dike to be mapped,[5] although its significance was not understood until similar structures had been described from Scotland. The rocks of the area are complex and have featured in international geological debate since the 1950s. The site has attracted geologists from all over the world and featured in theories to explain the unusual rock relationships. Some of these theories have now become an accepted part of geological science.[6]

Much of Slieve Gullion is covered with forest, heather, or raw stone, while 612 hectares of dry heath on the mountain has been designated a Special Area of Conservation,[7] an Environmentally Sensitive Area,[8] and an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. In July 2006, some areas of gorse were destroyed by a wildfire which may have been started deliberately.[9]

Traces of fields on the mountain's poor soil from farming in earlier times can still be seen. There is also evidence of past quarrying.

History

Burial cairns

There are two burial cairns on top of the hill, on either side of a small lake. The southern one is a large passage tomb, the highest surviving passage tomb in Ireland.[10] In 1961, a team of archaeologists explored the site and set up a 30-person camp near the summit.[11] The tomb's cairn is 30 m (98 ft) wide and 5 m (16 ft) high. The chamber inside is 3.6 m (12 ft) wide, with a corbelled roof up to 4.3 m (14 ft) high. It contained three large blocks of stone seemingly used as basins, and fragments of human bone. Some bits of worked flint and a barbed-end arrowhead were also found, "the meager remnants that survived the centuries of tomb raiding".[12] The entrance is aligned with the setting sun on the winter solstice.[13] Radiocarbon dating suggests it was built c.3500–2900 BCE.[14] The smaller cairn to the north of the lake was built later, perhaps during the Bronze Age. It contains two cist burials, with one containing bits of burnt bone; likely the remains of a single adult.[15]

The two cairns were disturbed by American soldiers training there during World War II.[16] Irish folklore holds that it is bad luck to damage or disrespect such tombs and that doing so could bring a curse.[17][18] Today they are historic monuments protected by law. In recent years, volunteers have helped to repair the burial cairns under the supervision of an archaeologist.[19]

Titus Oates Plot

Around 1680, religious persecution of local Irish Catholics heated up in reaction to Titus Oates' claims of a non-existent Catholic conspiracy aimed at assassinating King Charles II of England and massacring the Protestants of the British Isles. As a result, a Catholic priest named Fr. Mac Aidghalle was murdered while saying mass at a mass rock that still stands atop Slieve Gullion. The perpetrators were a company of redcoats under the command of a priest hunter named Turner. Redmond O'Hanlon, the outlawed but de facto Chief of the Name of Clan O'Hanlon and leading local rapparee, is said in local oral tradition to have avenged the murdered priest and in so doing to have sealed his own fate.[20]

Hillwalking

Slieve Gullion is popular with hillwalkers, with about 20,000 people climbing the hill every year. A road leads to a small car park about halfway up the western side of the mountain. From there a trail leads to the summit. There is also a waymarked trail from the northern side of the mountain. As there is no security on the mountainside, cars parked there are often broken into by thieves, and police have asked visitors not to leave valuables in cars.[21][22]

On the eastern side of the mountain is Slieve Gullion Forest Park, which includes a visitors' centre, café, playground, and the Giant's Lair Story Trail.[23]

Mythology

Slieve Gullion appears in Irish mythology.

Fionn and the Cailleach

In the tale known as The Hunt of Slieve Gullion, Áine and her sister Milucra both seek after the legendary hero Fionn mac Cumhaill (Finn McCool). Knowing that Áine vowed never to marry a man with grey hair, Milucra secretly puts a spell on the lake atop Slieve Gullion, so that anyone who swam in it would become elderly. She tricks Fionn by asking him to fetch her golden ring from the lake, and he emerges as an old man with grey-white hair. His men, the Fianna, force her to give him a restorative potion from her cornucopia. Fionn's youth returns, but his hair does not return to its true colour.[24] This is said to be the origin of his name, Fionn, meaning 'white'. In some versions of the tale, Milucra is revealed to be the Cailleach Bhéara (Calliagh Birra), an ancient goddess.[25]

The names of several features on the mountain refer to the Cailleach Bhéara. The passage grave is known as Calliagh Birra's House and the small lake is called Calliagh Birra's Lough. Lower down, on a hillock called Spellick, is a rock feature called the Calliagh Birra's Chair. Locals would visit it at Lughnasadh and take turns sitting on the chair.[26]

Cú Chulainn

Slieve Gullion is said to be where the legendary hero Cú Chulainn (Cuhullin) received his name and where he spent his childhood as Sétanta.

According to myth, the mountain is named after Culann the metalsmith. Culann invites Conchobhar mac Neasa, king of Ulster, to a feast at his house on the slopes of Slieve Gullion. On his way, Conchobhar stops at the playing field to watch the boys play hurling. He is so impressed by Sétanta's performance that he asks him to join him at the feast. Sétanta promises to join him after he finishes his game. Conchobhar goes ahead, but he forgets about Sétanta, and Culann lets loose his ferocious hound to guard his house. When Sétanta arrives, the hound attacks him, but he kills it; in one version by smashing it against a standing stone, in another by driving a sliotar (hurling ball) down its throat with his hurley. Culann is devastated by the loss of his hound, so Sétanta promises to rear him a replacement, and until it was old enough to do the job, he himself would guard Culann's house. The druid Cathbhadh announces that his name henceforth would be Cú Chulainn, "Culann's Hound".

In the Táin Bó Cuailnge, the nearby Gap of the North is where Cú Chulainn single-handedly fends-off the army of queen Méabh.[27]

See also

References

- ↑ "Cooley/Gullion Area - Slieve Gullion". MountainViews. Ordnance Survey Ireland. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ↑ "Slieve Gullion". PlaceNames NI. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ↑ T.S. Ó Máille (1960) "Cuileann in áitainmneacha", in 'Béaloideas', Journal of the Folklore of Ireland Society XXVIII.

- ↑ Christopher Somerville – 13 June 2009 (13 June 2009). "Walk of the week: Slieve Gullion Co Armagh by Christopher Somerville, Irish Independent, Saturday June 13 2009". Independent.ie. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Slieve Gullion Ring - Overview". Habitas.org.uk. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ↑ "Geology within Ring of Gullion AONB". Doeni.gov.uk. 19 January 2010. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ↑ "Slieve Gullion Special Area of Conservation". Jncc.gov.uk. 25 March 2010. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ↑ "Environmentally Sensitive Areas (Slieve Gullion) Designation (Amendment) Order (Northern Ireland) 1997". Opsi.gov.uk. 17 June 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ↑ FireFightingNews.com (21 July 2006). "Arsonists Strike 2,500 Times In Ulster In Last Three Years". Firefightingnews.com. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ↑ "Slieve Gullion, County Armagh". Mythicalireland.com. 16 March 2000. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ↑ Collins, A.E.P., and B.C.S. Wilson. "The Slieve Gullion Cairns" in the Ulster Journal of Archaeology (1963). p.19.

- ↑ Collins, A.E.P. "The Slieve Gullion Passage-Grave Cairn". Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society 5.1 (1969). pp.180-182

- ↑ 'Mystery and magic in megalithic Ireland' Irish Times, December 3rd, 2011

- ↑ Waddell, John. The Prehistoric Archaeology of Ireland. Wordwell, 2005. p.77

- ↑ Collins & Wilson, pp.31-33

- ↑ Collins & Wilson, p.24

- ↑ Sarah Champion & Gabriel Cooney. "Chapter 13: Naming the Places, Naming the Stones". Archaeology and Folklore. Routledge, 2005. p.193

- ↑ Doherty, Gillian. The Irish Ordnance Survey: History, Culture and Memory. Four Courts Press, 2004. p.89

- ↑ "Slieve Gullion: Volunteers help repair ancient cairn". BBC News. 18 May 2015.

- ↑ Tony Nugent (2013), Were You at the Rock? The History of Mass Rocks in Ireland, The Liffey Press. Pages 80-81.

- ↑ "Vigilance urged after Slieve Gullion Forest Park robberies". Newry Times. 22 August 2017.

- ↑ "Slieve Gullion Park theft prompts police investigation". Newry Times. 8 November 2013.

- ↑ Slieve Gullion Forest Park

- ↑ Monaghan, Patricia. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. Infobase Publishing, 2004. p.109

- ↑ Gregory, Isabella Augusta (Persse). Gods and Fighting Men. John Murray, 1904. pp. 306-09

- ↑ Tempan, Paul. Irish Hill and Mountain Names. MountainViews.ie.

- ↑ Gribben, Arthur. "Táin Bó Cuailnge: A Place on the Map, A Place in the Mind". Western Folklore (1990). p.285