Somali nationalism (Somali: Soomaalinimo) is centered on uniting the Somali people who share a common language, religion, culture and ethnicity, and as such constitute a nation unto themselves. The ideology's earliest manifestations in the medieval era are traced to the Adalites whilst in the contemporary era its often traced back to SYL, the first Somali nationalist political organization to be formed was the Somali National League (SNL), established in 1935 in the former British Somaliland protectorate. In the country's northeastern, central and southern regions, the similarly-oriented Somali Youth Club (SYC) was founded in 1943 in Italian Somaliland, just prior to the trusteeship period. The SYC was later renamed the Somali Youth League (SYL) in 1947. It became the most influential political party in the early years of post-independence Somalia.[1] The Somali guerilla militia Al-Shabab is noteworthy for incorporating Somali nationalism into its Islamist ideology.[2][3]

History

| History of Somalia |

|---|

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) |

|

|

Early Somali nationalism developed in the beginning of the 20th century with the concept of "Greater Somalia" that encompassed a theme, Somalis are a nation with a distinct identity and wanted to unite inhabited areas of Somali clans. Pan-Somalism refers to the vision of reunifying these areas to form a single Somali nation. The pursuit of this goal has led to conflict: Somalia engaged after World War II in the Ogaden War with Ethiopia over the Ogaden region, and supported Somali insurgents against Kenya.

Prehistory

Somalia has been inhabited since at least the Paleolithic. During the Stone Age, the Doian and Hargeisan cultures flourished here.[4] The oldest evidence of burial customs in the Horn of Africa comes from cemeteries in Somalia dating back to the 4th millennium BCE.[5] The stone implements from the Jalelo site in the north were also characterized in 1909 as important artefacts demonstrating the archaeological universality during the Paleolithic between the East and the West.[6]

According to linguists, the first Afroasiatic-speaking populations arrived in the region during the ensuing Neolithic period from the family's proposed urheimat ("original homeland") in the Nile Valley,[7] or the Near East.[8]

The Laas Geel complex on the outskirts of Hargeisa in Somaliland dates back around 5,000 years, and has rock art depicting both wild animals and decorated cows.[9] Other cave paintings are found in the northern Dhambalin region, which feature one of the earliest known depictions of a hunter on horseback. The rock art is in the distinctive Ethiopian-Arabian style, dated to 1,000 to 3,000 BCE.[10][11] Additionally, between the towns of Las Khorey and El Ayo in Somaliland lies Karinhegane, the site of numerous cave paintings of real and mythical animals. Each painting has an inscription below it, which collectively have been estimated to be around 2,500 years old.[12][13]

Antiquity and classical era

Ancient pyramidical structures, mausoleums, ruined cities and stone walls, such as the Wargaade Wall, are evidence of an old civilization that once thrived in the Somali peninsula.[14][15] This civilization enjoyed a trading relationship with Ancient Egypt and Mycenaean Greece since the second millennium BCE, supporting the hypothesis that Somalia or adjacent regions were the location of the ancient Land of Punt.[14][16] The Puntites traded myrrh, spices, gold, ebony, short-horned cattle, ivory and frankincense with the Egyptians, Phoenicians, Babylonians, Indians, Chinese and Romans through their commercial ports. An Egyptian expedition sent to Punt by the 18th dynasty Queen Hatshepsut is recorded on the temple reliefs at Deir el-Bahari, during the reign of the Puntite King Parahu and Queen Ati.[14]

The one-humped camel or dromedary is believed to have been domesticated between the 3rd and 2nd millennium BCE, possibly in Somalia.[17] In the classical period, the city-states of Mosylon, Opone, Mundus, Isis, Malao, Avalites, Essina, Nikon and Tabae developed a lucrative trade network connecting with merchants from Phoenicia, Ptolemaic Egypt, Greece, Parthian Persia, Saba, Nabataea, and the Roman Empire. They used the ancient Somali maritime vessel known as the beden to transport their cargo.

After the Roman conquest of the Nabataean Empire and the Roman naval presence at Aden to curb piracy, Arab and Somali merchants agreed with the Romans to bar Indian ships from trading in the free port cities of the Arabian peninsula[18] to protect the interests of Somali and Arab merchants in the lucrative commerce between the Red and Mediterranean Seas.[19] However, Indian merchants continued to trade in the port cities of the Somali peninsula, which was free from Roman interference.[20]

For centuries, Indian merchants brought large quantities of cinnamon to Somalia and Arabia from Ceylon and the Spice Islands. The source of the cinnamon and other spices is said to have been the best-kept secret of Arab and Somali merchants in their trade with the Roman and Greek world; the Romans and Greeks believed the source to have been the Somali peninsula.[21] The collusive agreement among Somali and Arab traders inflated the price of Indian and Chinese cinnamon in North Africa, the Near East, and Europe, and made the cinnamon trade a very profitable revenue generator, especially for the Somali merchants through whose hands large quantities were shipped across sea and land routes.[19]

Birth of Islam and the Middle Ages

Islam was introduced to the area early on from the Arabian peninsula, shortly after the hijra. Zeila's two-mihrab Masjid al-Qiblatayn dates to the 7th century, and is the oldest mosque in the city.[22] In the late 9th century, Al-Yaqubi wrote that Muslims were living along the northern Somali seaboard.[23] He also mentioned that the Adal kingdom had its capital in the city,[23][24] suggesting that the Adal Sultanate with Zeila as its headquarters dates back to at least the 9th or 10th centuries. According to I.M. Lewis, the polity was governed by local dynasties consisting of Somalized Arabs or Arabized Somalis, who also ruled over the similarly established Sultanate of Mogadishu in the Benadir region to the south. Adal's history from this founding period forth would be characterized by a succession of battles with neighbouring Abyssinia.[24] At its height, the Adal kingdom controlled large parts of modern-day Somaliland, Ethiopia, Djibouti, and Eritrea.

In 1332, the Zeila-based King of Adal was slain in a military campaign aimed at halting Abyssinian emperor Amda Seyon I's march toward the city.[25] When the last Sultan of Ifat, Sa'ad ad-Din II, was also killed by Emperor Dawit I in Zeila in 1410, his children escaped to Yemen, before returning in 1415.[26] In the early 15th century, Adal's capital was moved further inland to the town of Dakkar, where Sabr ad-Din II, the eldest son of Sa'ad ad-Din II, established a new base after his return from Yemen.[27][28]

Adal's headquarters were again relocated the following century, this time southward to Harar. From this new capital, Adal organised an effective army led by Imam Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (Ahmad "Gurey" or "Gran"; both meaning "the left-handed") that invaded the Abyssinian empire.[28] This 16th-century campaign is historically known as the Conquest of Abyssinia (Futuh al-Habash). During the war, Imam Ahmad pioneered the use of cannons supplied by the Ottoman Empire, which he imported through Zeila and deployed against Abyssinian forces and their Portuguese allies led by Cristóvão da Gama.[29] Some scholars argue that this conflict proved, through their use on both sides, the value of firearms such as the matchlock musket, cannon, and the arquebus over traditional weapons.[30]

During the Ajuran period, the sultanates and republics of Merca, Mogadishu, Barawa, Hobyo and their respective ports flourished and had a lucrative foreign commerce, with ships sailing to and coming from Arabia, India, Venetia,[32] Persia, Egypt, Portugal, and as far away as China. Vasco da Gama, who passed by Mogadishu in the 15th century, noted that it was a large city with houses several storeys high and large palaces in its centre, in addition to many mosques with cylindrical minarets.[33]

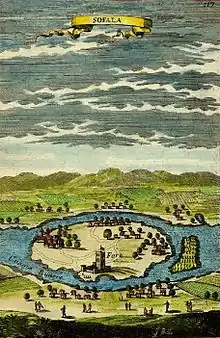

In the 16th century, Duarte Barbosa noted that many ships from the Kingdom of Cambaya in modern-day India sailed to Mogadishu with cloth and spices, for which they in return received gold, wax and ivory. Barbosa also highlighted the abundance of meat, wheat, barley, horses, and fruit on the coastal markets, which generated enormous wealth for the merchants.[34] Mogadishu, the center of a thriving textile industry known as toob benadir (specialized for the markets in Egypt, among other places[35]), together with Merca and Barawa, also served as a transit stop for Swahili merchants from Mombasa and Malindi and for the gold trade from Kilwa.[36] Jewish merchants from the Hormuz brought their Indian textile and fruit to the Somali coast in exchange for grain and wood.[37]

Trading relations were established with Malacca in the 15th century,[38] with cloth, ambergris and porcelain being the main commodities of the trade.[39] Giraffes, zebras and incense were exported to the Ming Empire of China, which established Somali merchants as leaders in the commerce between the Asia and Africa[40] and influenced the Chinese language with the Somali language in the process. Hindu merchants from Surat and Southeast African merchants from Pate, seeking to bypass both the Portuguese blockade and Omani interference, used the Somali ports of Merca and Barawa (which were out of the two powers' jurisdiction) to conduct their trade in safety and without interference.[41]

Early Modern Era and the Scramble for Africa

In the early modern period, successor states of the Adal, Ajuran and Hiraab Imamate, Hiraab began to flourish in Somalia. These included the Warsangali Sultanate, the Bari Dynasties, the Sultanate of Geledi (Gobroon dynasty), the Majeerteen Sultanate (Migiurtinia), and the Sultanate of Hobyo (Obbia). They continued the tradition of castle-building and seaborne trade established by previous Somali empires.

Sultan Yusuf Mahamud Ibrahim, the third Sultan of the House of Gobroon, started the golden age of the Gobroon Dynasty. His army came out victorious during the Bardheere Jihad, which restored stability in the region and revitalized the East African ivory trade. He also received presents from and had cordial relations with the rulers of neighbouring and distant kingdoms such as the Omani, Witu and Yemeni Sultans.

Sultan Ibrahim's son Ahmed Yusuf succeeded him and was one of the most important figures in 19th-century East Africa, receiving tribute from Omani governors and creating alliances with important Muslim families on the East African coast. In northern Somalia, the Gerad Dynasty conducted trade with Yemen and Persia and competed with the merchants of the Bari Dynasty. The Gerads and the Bari Sultans built impressive palaces and fortresses and had close relations with many different empires in the Near East.

In the late 19th century, after the Berlin conference of 1884, European powers began the Scramble for Africa, whereupon the Darawiish built Dhulbahante garesas to counter colonialism. Darawiish social structure included the haroun (i.e. Darawiish government) under Faarax Sugulle, the Darawiish & Dhulbahante king Diiriye Guure and its emir Sayid Mohamed, which collectively carved out a powerful state in Ciid-Nugaal which was subdivided into 13 administrative divisions of which the four largest, Shiikhyaale, Dooxato, Golaweyne, Miinanle were near exclusively Dhulbahante. The other administrative divisions, Taargooye, Dharbash, Indhabadan, Burcadde-Godwein, Garbo (Darawiish), Ragxun, Gaarhaye, Bah-udgoon and Shacni-cali were collectively also overwhelmingly Dhulbahante.[42] The Dervish movement successfully repulsed the British Empire four times and forced it to retreat to the coastal region.[43]

The Darawiish defeated the colonial powers on numerous occasions, most notably, the 1903 victory at Cagaarweyne commanded by Suleiman Aden Galaydh[44] or the killing of general Richard Corfield by Ibraahin Xoorane in 1913,[45] and theses repulsions forcing the British Empire to retreat to the coastal region in the late 1900s.[46] The only two notable defeats of the Darawiish were both commanded by Haji Yusuf Barre, the first time at Jidbaali in 1904, and the second time at the last stand at Taleh when the Dervishes were finally defeated in 1920 by British airpower.[47]

The dawn of fascism in the early 1920s heralded a change of strategy for Italy, as the north-eastern sultanates were soon to be forced within the boundaries of La Grande Somalia according to the plan of Fascist Italy. With the arrival of Governor Cesare Maria De Vecchi on 15 December 1923, things began to change for that part of Somaliland known as Italian Somaliland. Italy had access to these areas under the successive protection treaties, but not direct rule.

The Fascist government had direct rule only over the Benadir territory. Fascist Italy, under Benito Mussolini, attacked Abyssinia (Ethiopia) in 1935, with an aim to colonize it. The invasion was condemned by the League of Nations, but little was done to stop it or to liberate occupied Ethiopia. On 3 August 1940, Italian troops, including Somali colonial units, crossed from Ethiopia to invade British Somaliland, and by 14 August, succeeded in taking Berbera from the British.

A British force, including troops from several African countries, launched the campaign in January 1941 from Kenya to liberate British Somaliland and Italian-occupied Ethiopia and conquer Italian Somaliland. By February, most of Italian Somaliland was captured and in March, British Somaliland was retaken from the sea. The forces of the British Empire operating in Somaliland comprised the three divisions of South African, West African, and East African troops. They were assisted by Somali forces led by Abdulahi Hassan with Somalis of the Isaaq, Dhulbahante, and Warsangali clans prominently participating.

Ogaden campaign

In July 1977, the Ogaden War against Ethiopia broke out after Barre's government sought to incorporate the predominantly Somali-inhabited Ogaden region into a Pan-Somali Greater Somalia. In the first week of the conflict, Somali armed forces took southern and central Ogaden and for most of the war, the Somali army scored continuous victories on the Ethiopian army and followed them as far as Sidamo. By September 1977, Somalia controlled 90% of the Ogaden and captured strategic cities such as Jijiga and put heavy pressure on Dire Dawa, threatening the train route from the latter city to Djibouti. After the siege of Harar, a massive unprecedented Soviet intervention consisting of 20,000 Cuban forces and several thousand Soviet advisers came to the aid of Ethiopia's communist Derg regime. By 1978, the Somali troops were ultimately pushed out of the Ogaden. This shift in support by the Soviet Union motivated the Barre government to seek allies elsewhere. It eventually settled on the Soviet Union's Cold War arch-rival, the United States, which had been courting the Somali government for some time. All in all, Somalia's initial friendship with the Soviet Union and later partnership with the United States enabled it to build the largest army in Africa.[48]

Gallery

Somali Youth League was the first political party in Somalia and played a key role in the nation's road to independence.

Somali Youth League was the first political party in Somalia and played a key role in the nation's road to independence. Ruins of Qa’ableh

Ruins of Qa’ableh

A Dhulbahante garesa in Taleex, the dervish capital

A Dhulbahante garesa in Taleex, the dervish capital

See also

References

- ↑ Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi. Culture and Customs of Somalia. Westport, Connecticut, Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc, 2001. p. 25.

- ↑ Makhaus, Ken (August 2009). "Somalia: What went Wrong?". The RUSI Journal. 154 (4): 8. doi:10.1080/03071840903216395. S2CID 219626653.

- ↑ Allen, William; Gakuo Mwangi, Oscar (25 March 2021). "Al-Shabaab". Oxford Research Encyclopedias: African History. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.785. ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4. Archived from the original on 29 December 2022.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ Peter Robertshaw (1990). A History of African Archaeology. J. Currey. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-435-08041-9.

- ↑ Brandt, S. A. (1988). "Early Holocene Mortuary Practices and Hunter-Gatherer Adaptations in Southern Somalia". World Archaeology. 20 (1): 40–56. doi:10.1080/00438243.1988.9980055. JSTOR 124524. PMID 16470993.

- ↑ H. W. Seton-Karr (1909). "Prehistoric Implements From Somaliland". 9 (106). Man: 182–183. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Zarins, Juris (1990), "Early Pastoral Nomadism and the Settlement of Lower Mesopotamia", (Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research)

- ↑ Diamond J, Bellwood P (2003) "Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions" Science 300, doi:10.1126/science.1078208

- ↑ Bakano, Otto (24 April 2011). "Grotto galleries show early Somali life". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ↑ Mire, Sada (2008). "The Discovery of Dhambalin Rock Art Site, Somaliland". African Archaeological Review. 25 (3–4): 153–168. doi:10.1007/s10437-008-9032-2. S2CID 162960112. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ↑ Alberge, Dalya (17 September 2010). "UK archaeologist finds cave paintings at 100 new African sites". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 June 2013.

- ↑ Hodd, Michael (1994). East African Handbook. Trade & Travel Publications. p. 640. ISBN 0844289833.

- ↑ Ali, Ismail Mohamed (1970). Somalia Today: General Information. Ministry of Information and National Guidance, Somali Democratic Republic. p. 295.

- 1 2 3 Njoku, Raphael Chijioke (2013). The History of Somalia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 29–31. ISBN 978-0313378577.

- ↑ Dalal, Roshen (2011). The Illustrated Timeline of the History of the World. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 131. ISBN 978-1448847976.

- ↑ Abdel Monem A. H. Sayed, Zahi A. Hawass (ed.) (2003). Egyptology at the Dawn of the Twenty-first Century: Archaeology. American Univ in Cairo Press. pp. 432–433. ISBN 9774246748.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ↑ Suzanne Richard (2003) Near Eastern archaeology: a reader, EISENBRAUNS, p. 120 ISBN 1-57506-083-3.

- ↑ Warmington 1995, p. 54.

- 1 2 Warmington 1995, p. 229.

- ↑ Warmington 1995, p. 187.

- ↑ Warmington 1995, pp. 185–6.

- ↑ Briggs, Phillip (2012). Somaliland. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 7. ISBN 978-1841623719.

- 1 2 Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 25. Americana Corporation. 1965. p. 255.

- 1 2 I. M. Lewis (1955). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho. International African Institute. p. 140.

- ↑ M. Th. Houtsma (1987). E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. BRILL. pp. 125–126. ISBN 9004082654.

- ↑ Nizar Hamzeh, A.; Hrair Dekmejian, R. (2010). "A Sufi Response to Political Islamism: Al-Abāsh of Lebanon". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 28 (2): 217–229. doi:10.1017/S0020743800063145. S2CID 154765577.

- ↑ Briggs, Philip (2012). Bradt Somaliland: With Addis Ababa & Eastern Ethiopia. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 10. ISBN 978-1841623719.

- 1 2 Lewis, I. M. (1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. James Currey Publishers. p. 17. ISBN 0852552807.

- ↑ Lewis, I.M. (1999) A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa, LIT Verlag Münster, p. 17, ISBN 3825830845.

- ↑ Black, Jeremy (1996) Cambridge Illustrated Atlas, Warfare: Renaissance to Revolution, 1492–1792, Cambridge University Press, p. 9, ISBN 0521470331.

- ↑ Terry H. Elkiss. The quest for an African Eldorado: Sofala. p. 4.

- ↑ Fage, John Donnelly; Oliver, Roland Anthony (1970). Papers in African Prehistory. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521095662.

- ↑ E. G. Ravenstein (2010). A Journal of the First Voyage of Vasco Da Gama, 1497–1499. Cambridge University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-108-01296-6.

- ↑ Sir Reginald Coupland (1965) East Africa and its invaders: from the earliest times to the death of Seyyid Said in 1856, Russell & Russell, p. 38.

- ↑ Edward A. Alpers (2009). East Africa and the Indian Ocean. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-55876-453-8.

- ↑ Nigel Harris (2003). The Return of Cosmopolitan Capital: Globalization, the State and War. I.B.Tauris. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-1-86064-786-4.

- ↑ R. J. Barendse (2002). The Arabian Seas: The Indian Ocean world of the Seventeenth Century /c R.J. Barendse. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 343–. ISBN 978-0-7656-0729-4.

- ↑ Alpers 1976.

- ↑ Caroline Sassoon (1978) Chinese Porcelain Marks from Coastal Sites in Kenya: Aspects of Trade in the Indian Ocean, XIV–XIX Centuries, Vol. 43–47, British Archaeological Reports, p. 2, ISBN 0860540189.

- ↑ Sir Reginald Coupland (1965) East Africa and Its Invaders: From the Earliest Times to the Death of Seyyid Said in 1856, Russell & Russell, p. 37.

- ↑ Edward A. Alpers (2009). East Africa and the Indian Ocean. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-55876-453-8.

- ↑ Ciise, Jaamac (1976). Taariikhdii daraawiishta iyo Sayid Maxamad Cabdille Xasan. p. 175.

- ↑ Kevin Shillington, Encyclopedia of African History (CRC Press, 2005), p. 1406.

- ↑ "THE FIGHT IN SOMALILAND.|1904-01-02|Rhyl Record and Advertiser - Welsh Newspapers".

- ↑ Taariikhdii daraawiishta iyo Sayid Maxamad Cabdille Xasan, Jaamac Cumar Ciise · 2005 , PAGE 275

- ↑ Kevin Shillington, Encyclopedia of African history, (CRC Press: 2005), p. 1406.

- ↑ Samatar, Said Sheikh (1982). Oral Poetry and Somali Nationalism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 131, 135. ISBN 0-521-23833-1.

- ↑ Oliver Ramsbotham, Tom Woodhouse, Encyclopedia of international peacekeeping operations, (ABC-CLIO: 1999), p.222.