Balochistan

بلۏچستان | |

|---|---|

Balochistan region in pink | |

| Countries | |

| Population (2013) | |

| • Total | c. 18–19 million[1][2][3] |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic groups | Baloch, Pashtuns, Gurjar, Hazara, Sindhi, Saraiki |

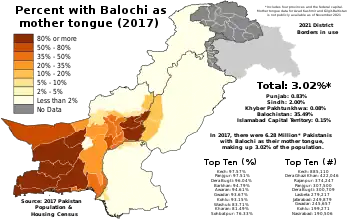

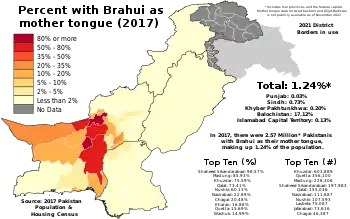

| • Languages | Balochi Minor: Brahui, Dehwari, Pashto, Lasi, Sindhi, Saraiki, Dari, Persian, Hazaragi, Khetrani, Urdu |

| Largest cities | |

Balochistan[4] (/bəˈlɒtʃɪstɑːn, bəˌlɒtʃɪˈstɑːn, -stæn/ bə-LOTCH-ist-a(h)n, -A(H)N; Balochi: بلۏچستان; also romanised as Baluchistan and Baluchestan) is a historical region in Western and South Asia, located in the Iranian plateau's far southeast and bordering the Indian Plate and the Arabian Sea coastline. This arid region of desert and mountains is primarily populated by ethnic Baloch people.[5][6][7]

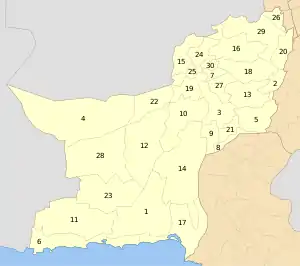

The Balochistan region is split among three countries: Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Administratively it comprises the Pakistani province of Balochistan, the Iranian province of Sistan and Baluchestan, and the southern areas of Afghanistan, which include Nimruz, Helmand and Kandahar provinces.[8][9] It borders the Khyber Paktunkhwa region to the north, Sindh and Punjab to the east, and Iranian regions to the west. Its southern coastline, including the Makran Coast, is washed by the Arabian Sea, in particular by its western part, the Gulf of Oman.

Etymology

The name "Balochistan" is generally believed to derive from the name of the Baloch people.[8] Since the Baloch people are not mentioned in pre-Islamic sources, it is likely that the Baloch were known by some other name in their place of origin and that they acquired the name "Baloch" only after arriving in Balochistan sometime in the 10th century.[10]

Johan Hansman relates the term "Baloch" to Meluḫḫa, the name by which the Indus Valley civilisation is believed to have been known to the Sumerians (2900–2350 BC) and Akkadians (2334–2154 BC) in Mesopotamia.[11] Meluḫḫa disappears from the Mesopotamian records at the beginning of the second millennium BC.[12] However, Hansman states that a trace of it in a modified form, as Baluḫḫu, was retained in the names of products imported by the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC).[13] Al-Muqaddasī, who visited the capital of Makran - Bannajbur, wrote c. 985 AD that it was populated by people called Balūṣī (Baluchi), leading Hansman to postulate "Baluch" as a modification of Meluḫḫa and Baluḫḫu.[14]

Asko Parpola relates the name Meluḫḫa to Indo-Aryan words mleccha (Sanskrit) and milakkha/milakkhu (Pali) etc., which do not have an Indo-European etymology even though they were used to refer to non-Aryan people. Taking them to be proto-Dravidian in origin, he interprets the term as meaning either a proper name milu-akam (from which tamilakam was derived when the Indus people migrated south) or melu-akam, meaning "high country", a possible reference to Balochistani high lands.[15] Historian Romila Thapar also interprets Meluḫḫa as a proto-Dravidian term, possibly mēlukku, and suggests the meaning "western extremity" (of the Dravidian-speaking regions in the Indian subcontinent). A literal translation into Sanskrit, aparānta, was later used to describe the region by the Indo-Aryans.[16]

During the time of Alexander the Great (356–323 BC), the Greeks called the land Gedrosia and its people Gedrosoi, terms of unknown origin.[17] Using etymological reasoning, H. W. Bailey reconstructs a possible Iranian name, uadravati, meaning "the land of underground channels", which could have been transformed to badlaut in the 9th century and further to balōč in later times. This reasoning remains speculative.[18]

History

The earliest evidence of human occupation in what is now Balochistan is dated to the Paleolithic era. Evidence includes hunting camps, lithic scatter, and chipped and flaked stone tools. The earliest settled villages in the region date to the ceramic Neolithic (c. 7000–6000 BCE) and included the site of Mehrgarh in the Kachi Plain. These villages expanded in size during the subsequent Chalcolithic when interaction was amplified. This involved the movement of finished goods and raw materials, including chank shell, lapis lazuli, turquoise, and ceramics. By 2500 BCE (the Bronze Age), the region now known as Pakistani Balochistan had become part of the Indus Valley civilization cultural orbit,[19] providing key resources to the expansive settlements of the Indus river basin to the east.

Classical period

From the 1st century to the 3rd century CE, the region was ruled by the Pāratarājas (lit. "Pārata Kings"), a dynasty of Indo-Parthian kings. The dynasty of the Pāratas is thought to be identical with the Pāradas of the Mahabharata, the Puranas and other Vedic and Iranian sources.[20] The Parata kings are primarily known through their coins, which typically exhibit the bust of the ruler (with long hair in a headband) on the obverse, and a swastika within a circular legend on the reverse, written in Brahmi (usually silver coins) or Kharoshthi (copper coins). These coins are mainly found in Loralai in today's western Pakistan.

During the wars between Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) and Emperor Darius III (336-330 BC), the Baloch were allied with the last Achaemenid emperor. According to Shustheri (1925), Darius III, after much hesitation, assembled an army at Arbela to counter the army of invading Greeks. His cousin Besius was the commander, leading the horsemen from Balkh. Berzanthis was the commander of the Baloch forces, Okeshthra was the commander of the forces from Khuzistan, Maseus was the commander of the Syrian and Egyptian contingent, Ozbed was the commander of the Medes, and Phirthaphirna was leading the Sakas and forces from Tabaristan, Gurgan, and Khurasan. Obviously, as part of a losing side, the Baloch certainly got their share of punishment from the victorious Macedonian forces.[21]

Herodotus in 450 BCE described the Paraitakenoi as a tribe ruled by Deiokes, a Persian king, in northwestern Persia (History I.101). Arrian describes how Alexander the Great encountered the Pareitakai in Bactria and Sogdiana, and had them conquered by Craterus (Anabasis Alexandrou IV). The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (1st century CE) describes the territory of the Paradon beyond the Ommanitic region, on the coast of modern Balochistan.[22]

Medieval period

During the reign of Arab dynasties, medieval Iran suffered the onslaught of Ghaznavids, Mongols, Timurids, and the incursions of Guzz Turks. The relationship between the Baloch and nearly all these powers were hostile, and the Baloch suffered enormously during this long period. The Baloch encounters with these powers and the subsequent Baloch miseries forced the Baloch tribes to move from the areas of conflicts and to settle in the farflung and inaccessible regions. The bloody conflicts with Buyids and Seljuqs were instrumental in waves of migration by the Baloch tribes from Kerman to further east.[23]

The Hindu Sewa Dynasty ruled parts of Balochistan, chiefly Kalat.[24][25] The Sibi Division, which was carved out of Quetta Division and Kalat Division in 1974, derives its name from Rani Sewi, the queen of the Sewa dynasty.[26]

_-_Geographicus_-_RegnumPersicum-ottens-1730_(Mecran).jpg.webp)

The region was fully Islamized by the 9th century and became part of the territory of the Saffarids of Zaranj, followed by the Ghaznavids, then the Ghorids. The relation between the Ghaznavids and the Baloch had never been peaceful. Turan and Makuran came under the Ghaznavids founder Sebuktegin's suzerainty as early as AD 976-977 (Bosworth, 1963). The Baloch tribes fought against Sebuktegin when he attacked Khuzdar in AD 994. The Baloch were in the army of Saffarids Amir Khalaf and fought against Mahmud when the Ghaznavids forces invaded Sistan in AD 1013 (Muir, 1924). Many other occasions were mentioned by the historians of the Ghaznavids era in which the Baloch came into confrontation with the Ghaznavids forces (Nizam al-Mulk, 1960).[27]

There are only passing references of Baloch encounters with the Mongol hordes. In one of the classical Balochi ballads, there is mention of a Baloch chieftain, Shah Baloch, who, no doubt, heroically resisted a Mongol advance somewhere in Sistan.

During the long period of en masse migrations, the Baloch were traveling through settled territories, and it could not have been possible to survive simply as wandering nomads. Perpetual migrations, hostile attitudes of other tribes and rulers, and adverse climactic conditions ruined much of their cattle breeding. Settled agriculture became a necessity for the survival of herds and an increased population. They began to combine settled agriculture with animal husbandry. The Baloch tribes now consisted of sedentary and nomadic population, a composition that remained an established feature of the Baloch tribes until recently.[28]

The Khanate of Kalat was the first unified polity to emerge in the history of Balochistan.[29] It took birth from the confederacy of nomadic Brahui tribes native to the central Balochistan in 1666[30] which under Mir Ahmad Khan I declared independence from the Mughal suzeraignty[29] and slowly absorbed the Baloch principalities in the region.[30] It was ruled over by the Brahui Ahmadzai dynasty till 1948.[31][32] Ahmad Shah Durrani made it vassal of the Afghan Durrani Empire in 1749. In 1758 the Khan of Kalat, Mir Naseer Khan I, revolted against Ahmed Shah Durrani, defeated him, and made his Khanate independent from the Durrani Empire.

Tribalism and nomadism

Baloch tribalism in medieval times was synonymous with pastoral nomadism. Nomadic people, as observed by Heape (1931), regard themselves as the superior of sedentary or agriculturist. It is, perhaps, because the occupation of nomads made them strong, active, and inured to hardship and the dangers which beset a mobile life.[33]

The areas of Balochistan where the Baloch tribes moved in had a sedentary population, and the Baloch tribes were compelled to deal with their sedentary neighbors. Being in a weaker position, the Baloch tribes were in need of constant vigils for their survival in new lands. To deal with this problem, they began to make alliances and organized themselves into a more structured way. The structural solution to this problem was to create tribal confederacies or unions. Thus, in conditions of insecurity and disorder or when threatened by a predatory regional authority or a hostile central government, several tribal communities would form a cluster around a chief who had demonstrated his ability to offer protection and security.[33]

British occupation

The British took over the area in 1839.[34]

In the 1870s, Baluchistan came under control of the British Indian Empire in colonial India.[35] The fundamental objective of the British to enter into a treaty agreement with the Khanate of Kalat was to provide a passage and supplies to the "Army of Indus" on its way to Kandahar through Shikarpur, Jacobabad (Khangadh), Dhadar, Bolan Pass, Quetta, and Khojak Pass. It is interesting to note that the British imperialist interests in Balochistan were not primarily economic as was the case with other regions of India. Rather, it was of a military and geopolitical nature. Their basic objective in their advent in Balochistan was to station garrisons so as to defend the frontiers of British India from any threat coming from Iran and Afghanistan.[34]

Beginning from 1840, there began a general insurrection against the British rule throughout Balochistan. The Baloch were not ready to accept their country as part of an occupied Afghanistan and to be ruled under a puppet Khan. The powerful Mari tribe rose in total revolt. The British retaliated with excessive force, and a British contingent under the command of Major Brown on May 11, 1840, attacked the Mari headquarter of Kahan and occupied Kahan Fort and the surrounding areas (Masson, 1974). The Mari forces withdrew from the area, regrouped, and in an ambush wiped out a whole convoy of British troops near Filiji, killing more than one hundred British troops.[34]

During the time of the Indian independence movement, "three pro-Congress parties were still active in Balochistan's politics", such as the Anjuman-i-Watan Baluchistan, which favoured a united India and opposed its partition.[36][37]

Post-colonial history

In 2021, there was an earthquake that killed dozens of people. This came to be known as the 2021 Balochistan earthquake. There were other major earthquakes in 2013 (2013 Balochistan earthquake and 2013 Saravan earthquake).[38]

Culture

The cultural values which are the pillars of the Baloch individual and national identity were firmly established during the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, a period which not only brought sufferings for the Baloch and forced them into en masse migrations but also brought fundamental sociocultural transformation of the Baloch society. An overlapping of pastoral ecology and tribal structure had shaped contemporary Baloch social values. The pastoralist nomadic way of life and the inclination to resist the assimilation attempts of various powerful ethnic identities shaped the peculiar Baloch ethnic identity. It was the persecution by strong and organized religions for the last two thousand years that has shaped their secular attitude about religion in social or community affairs. Their independent and stubborn behavior as the distinctive feature of the Baloch identity is consistent with their nomadic or agro-pastoral past.[39]

Med o Maraka, for resolution of disputes among the Baloch, is a much-honored tradition. In a broader context, it is, in a way, accepting the guilt by the accused or offender and asking for forgiveness from the affected party. Usually, the offender himself does this by going to the home of the affected person and asking for forgiveness.[40]

Dress code and personal upkeeping are among the cultural values, which distinguish a Baloch from others. The Baloch dress and personal upkeeping very much resemble the Median and Parthian ways. Surprisingly, no significant changes can be observed in the Balochi dress since the ancient times. A typical Balochi outfit consisted of loose-fitting and many-folded trousers held by garters, bobbed hair, shirt (qamis), and a head turban. Generally, both hair and beard were carefully curled, but, sometimes, they depended on long straight locks. A typical dress of a Baloch woman consists of a long frock and trouser (shalwaar) with a headscarf.[41][42]

Music

Zahirok is one of the most important and well-known balochi song genres, often described as the “Balochi classical music” by the Baloch themselves.[43][44]

Instruments in traditional Balochi music include suroz, donali, ghaychak, dohol, sorna, rubab, kemenche, tamburag and benju.[45][46][47][48][49]

Religion

Historically, there is no documented evidence of religious practices of the Baloch in ancient times. Many among the Baloch writers observed that the persecutions of the Baloch by the Sassanid emperors Shapur II and Khosrow II had a strong religious or sectarian element. They believed that there are strong indications that the Baloch were the followers of Mazdakian and Manichean sects of Zoroastrianism religion at the time of their fatal encounters with Sassanid forces. No elaborate structure of religious institutions has been discerned in the Baloch society during the Middle Ages. The Baloch converted to Islam (nearly all Baloch belong to the Sunni sect of Islam) after the Arab conquest of Balochistan during the seventh century.[50]

Governance and political disputes

The Balochistan region is administratively divided among three countries, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iran. The largest portion in area and population is in Pakistan, whose largest province (in land area) is Balochistan. An estimated 6.9 million of Pakistan's population is Baloch. In Iran there are about two million ethnic Baloch[51] and a majority of the population of the eastern Sistan and Baluchestan Province is of Baloch ethnicity. The Afghan portion of Balochistan includes the Chahar Burjak District of Nimruz Province, and the Registan Desert in southern Helmand and Kandahar provinces. The governors of Nimruz province in Afghanistan belong to the Baloch ethnic group. President Pervez Musharraf and the military are responsible for the worsening of the conflict in Balochistan.[52]

The Balochistan region has also experienced a number of insurgencies with separatist militants demanding independence of Baloch regions in the three countries to form "Greater Balochistan".[53] In Pakistan, insurgencies by separatist militants in Balochistan province have been fought in 1948, 1958–59, 1962–63 and 1973–1977, with a new ongoing low-intensity insurgency[54] beginning in 2003.[55] Historically, drivers of the conflict are reported to include "tribal divisions", the Baloch-Pashtun ethnic divisions, "marginalization by Punjabi interests", and "economic oppression".[56] However, over the years, insurgency waged by separatist militants declined as result of crackdown by Pakistani security forces, infighting among the separatist militants and assassinations of Baloch politicians willing to take part in Pakistan's democratic process by the separatist militants.[57] Separatist militants in Pakistan demand more autonomy and a greater share in the region's natural resources. The Baloch population in Pakistan has endured grave violations of human rights, which include extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and torture. These actions are purportedly perpetrated by state security forces and their associates.[58] In 2019, United States declared Baloch Liberation Army, one of the separatist militants fighting the government of Pakistan, a global terrorist group.[54]

In Iran, separatist fighting has reportedly not gained as much ground as the conflict in Pakistan,[59] but has grown and become more sectarian since 2012,[51] with the majority-Sunni Baloch showing a greater degree of Salafist and anti-Shia ideology in their fight against the Shia-Islamist Iranian government.[51] Separatist militants fighting in Iran demand more rights for ethnic Baloch living in Iran's Sistan and Baluchestan Province.[60]

See also

References

- ↑ Iran, Library of Congress, Country Profile . Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ↑ Afghanistan, The World Factbook . Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency (2013). "The World Factbook: Ethnic Groups". Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ↑ Other variations of the spelling, especially on French maps, include Beloutchistan and Baloutchistan also Baloch Land.

- ↑ Dashti, Naseer (October 2012). The Baloch and Balochistan: A Historical Account from the Beginning to the Fall of the Baloch State. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4669-5896-8.

- ↑ "The History of Baloch and Balochistan: A Critical Appraisal".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Dames, Mansel Longworth (1904). The Baloch Race: A Historical and Ethnological Sketch. Royal Asiatic Society.

- 1 2 Pillalamarri, Akhilesh (12 February 2016). "A Brief History of Balochistan". thediplomat.com. THE DIPLOMAT. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ "Human Rights in Balochistan: A Case Study in Failure and Invisibility". HuffPost. 25 March 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ Elfenbein, J. (1988), "Baluchistan iii. Baluchi Language and Literature", Encyclopaedia Iranica

- ↑ Parpola 2015, Ch. 17: "The identification of Meluhha with the Greater Indus Valley is now almost universally accepted."

- ↑ Hansman 1973, p. 564.

- ↑ Hansman 1973, p. 565.

- ↑ Hansman 1973, pp. 568–569.

- ↑ Parpola & Parpola 1975, pp. 217–220.

- ↑ Thapar 1975, p. 10.

- ↑ Bevan, Edwyn Robert (12 November 2015), The House of Seleucus, Cambridge University Press, p. 272, ISBN 978-1-108-08275-4

- ↑ Hansman 1973

- ↑ Doshi, Riddhi (17 May 2015). "What did Harappans eat, how did they look? Haryana has the answers". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on May 17, 2015.

- ↑ Tandon 2006, p. 183.

- ↑ "Encyclopedia Britannica | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ↑ Tandon 2006, pp. 201–202.

- ↑ Pillalamarri, Akhilesh. "A Brief History of Balochistan". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ↑ Fowle, T. C.; Rai, Diwan Jamiat (1923). Baluchistan. Directorate of Archives, Government of Balochistan. p. 100.

The Hindus of Kalat town may indeed be far more indigenous since they claim descent from the ancient Sewa dynasty that ruled Kalat long before the Brahui came to Baluchistan.

- ↑ Balochistan Through the Ages: Geography and history. Nisa Traders. 1979. p. 316.

The country up to and including Multan was conquered by the Arabs and the Hindu dynasty of Sind and probably also the Sewa dynasty of Kalat came to an end.

- ↑ Quddus, Syed Abdul (1990). The Tribal Baluchistan. Ferozsons. p. 49. ISBN 978-969-0-10047-4.

The Sibi division was carved out of the Quetta and Kalat Divisions in April, 1974, and comprises districts of Sibi, Kachhi, Nasirabad, Kohlu and Dera Bugti. The Division derives its name from the town of Sibi or Sewi. The local tradition attributes the origin of this name to Rani Sewi of the Sewa dynasty which ruled this part of the country in ancient times.

- ↑ "The Regions of Sind, Baluchistan, Multan and Kashmir: the Historical, Social and Economic Setting | Programme des Routes de la Soie". fr.unesco.org. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ↑ "Engaged review of contemporary art and thought". www.nakedpunch.com. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- 1 2 "Brahui". Encyclopedia Irannica.

- 1 2 Minahan, James (2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-659-1.

- ↑ "Mastung > History of district". Retrieved 28 June 2021.

The Brahui Khans of Qalat were dominant from the 17th century onwards until the arrival of the British in the 19th century.

- ↑ Siddiqi, Farhan Hanif (2012). The Politics of Ethnicity in Pakistan: The Baloch, Sindhi and Mohajir Ethnic Movements. Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-415-68614-3.

The Brahui Khanate of Kalat sits at the apex of...

- 1 2 "Gale - Institution Finder". galeapps.gale.com. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- 1 2 3 "History – Government of Balochistan". Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ↑ Henige, David P. (1970). Colonial Governors from the Fifteenth Century to the Present: A Comprehensive List. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 89. ISBN 9780299054403.

The British began to assume control over the rough desert region in extreme western India known as Baluchistan in the 1870s.

- ↑ Afzal, M. Rafique (2001). Pakistan: History and Politics 1947-1971. Oxford University Press. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-19-579634-6.

Besides the Balochistan Muslim League, three pro-Congress parties were still active in Balochistan's politics: the Anjuman-i Watan, the Jamiatul Ulama u Hind, and the Qalat State National Party.

- ↑ Ranjan, Amit (2018). Partition of India: Postcolonial Legacies. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780429750526.

Furthermore, Congress leadership of Balochistan was united and there was no disagreement over its president, Samad Khan Achakzai. On the other hand, Qazi Isa was the president of the League in Balochistan. Surprisingly, he was neither a Balochi nor a Sardar. Consequently, all Sardars except Jaffar Khan Jamali, were against Qazi Isa for contesting this seat.

- ↑ "Asian Disaster Reduction Center(ADRC)". www.adrc.asia. Retrieved 2023-06-05.

A 5.9 magnitude quake struck Balochistan province, Pakistan at 03:01 am on 7 October 2021 local time at a depth of 20km. According to the Disaster Management Authority, at least 20 people were killed and about 300 injured.

- ↑ "Balochi Culture". History Pak. 2013-05-29. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ↑ "Baloch | people | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ↑ "Balochi culture dress". Balochi culture dress. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- ↑ "The Baloch race. A historical and ethnological sketch". 1904.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "CULTURE: BUDDING LOVE FOR MUSIC".

- ↑ "Zahirok: The Musical Base of Baloch Minstrelsy".

- ↑ Frishkopf, Michael (2006). "Music of Makran: Traditional Fusion from Coastal Balochistan". Asian Music. University of Texas Press. 37 (2): 164–171. doi:10.1353/amu.2007.0002. Retrieved January 5, 2024 – via University of Alberta.

- ↑ Massoudieh, M. T. (2016-06-21). "BALUCHISTAN iv. Music of Baluchistan". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ↑ "Regional Music". Retrieved January 5, 2024.

- ↑ Khan, Badal. "Zahirok: The Musical Base of Baloch Minstrelsy".

- ↑ Hafeez, Somaiyah (2023-01-01). "Baloch music through history and time". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 2024-01-06.

- ↑ Boyajian, Vahe S. (19 December 2016). "Is There an Ethno-religious Aspect in Balochi Identity?". Iran and the Caucasus. 20 (3–4): 397–405. doi:10.1163/1573384X-20160309. Retrieved 2022-04-21.

- 1 2 3 Grassi, Daniele (20 October 2014). "Iran's Baloch insurgency and the IS". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ↑ "Ex-president Pervez Musharraf: From Pakistan military ruler to fugitive in murder cases". The Indian Express. 2023-02-05. Retrieved 2023-05-20.

- ↑ Shukla, Srijan (20 February 2020). "Who are Baloch Liberation Army? Insurgents who killed 30 in Pakistan in last one week". The Print (India).

- 1 2 "US declares Pakistan's separatist Baluchistan Liberation Army as terrorist group". The Indian Express. 3 July 2019.

- ↑ Hussain, Zahid (Apr 25, 2013). "The battle for Balochistan". Dawn. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ↑ Kupecz, Mickey (Spring 2012). "PAKISTAN'S BALOCH INSURGENCY: History, Conflict Drivers, and Regional Implications" (PDF). International Affairs Review. 20 (3): 106. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ↑ "Balochistan's Separatist Insurgency On The Wane Despite Recent Attack". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 18 April 2019.

- ↑ "The untold story of human rights violations in Balochistan: Unveiling the historical context". DNA India. Retrieved 2023-06-02.

- ↑ Bhargava, G. S. "How Serious Is the Baluch Insurgency?" Asian Tribune (April 12, 2007). Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ↑ "Suicide Attack Kills 27 Members of Iran's Revolutionary Guards". Haaretz. 13 February 2019.

Bibliography

- Hansman, John (1973), "A Periplus of Magan and Meluhha", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 36 (3): 553–587, doi:10.1017/S0041977X00119858, JSTOR 613582, S2CID 140709175

- Hansman, John (1975), "A further note on Magan and Meluhha (Notes and Communications)", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 38 (3): 609–610, doi:10.1017/s0041977x00048126, JSTOR 613711, S2CID 178684667

- Parpola, Asko; Parpola, Simo (1975), "On the relationship of the Sumerian toponym Meluhha and Sanskrit mleccha", Studia Orientalia, 46: 205–238

- Parpola, Asko (2015), The Roots of Hinduism: The Early Aryans and the Indus Civilization, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-022692-3

- Tandon, Pankaj (2006), "New light on the Pāratarājas" (PDF), Numismatic Chronicle, 166: 173–209, JSTOR 42666407

- Thapar, Romila (January 1975), "A Possible Identification of Meluḫḫa, Dilmun and Makan", Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 18 (1): 1–42, doi:10.1163/156852075x00010, JSTOR 3632219

Further reading

- Axmann, Martin (2019). "Baluchistan and the Baluch people". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Fabry, Philippe (1991) Balouchistan, le désert insoumis, Paris, Nathan Image, 136 p., ISBN 2-09-240036-3

External links

- Baluchistan is a map published by The Century Company

- Afghanistan, Beloochistan, etc. is a map from 1893 published by the American Methodist Church

- Balochistan Archives- Preserving our Past

.jpg.webp)