| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

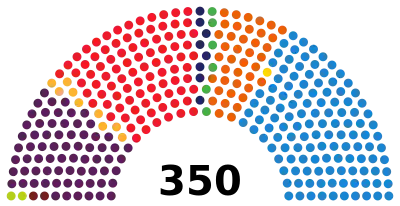

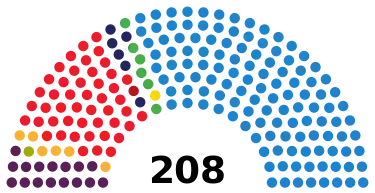

All 350 seats in the Congress of Deputies and 208 (of 266) seats in the Senate 176 seats needed for a majority in the Congress of Deputies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

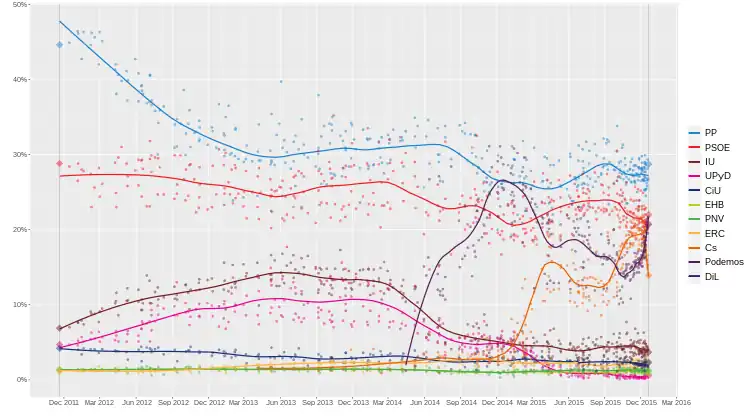

| Opinion polls | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Registered | 36,511,848 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout | 25,438,532 (69.7%) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

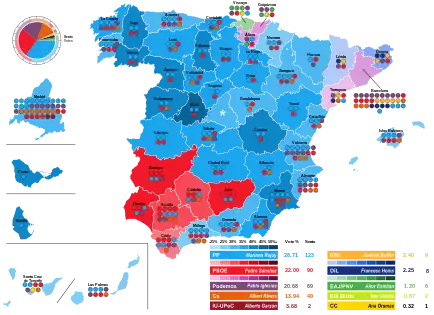

Election results by Congress of Deputies constituency | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 2015 Spanish general election was held on Sunday, 20 December 2015, to elect the 11th Cortes Generales of the Kingdom of Spain. All 350 seats in the Congress of Deputies were up for election, as well as 208 of 266 seats in the Senate. At exactly four years and one month since the previous general election, this remains the longest timespan between two general elections since the Spanish transition to democracy, and the only time in Spain a general election has been held on the latest possible date allowed under law.[1]

After a legislature plagued by the effects of an ongoing economic crisis, corruption scandals affecting the ruling party and social distrust with traditional parties, the election resulted in the most fragmented Spanish parliament up to that time. While the People's Party (PP) of incumbent prime minister Mariano Rajoy emerged as the largest party overall, it obtained its worst result since 1989. The party's net loss of 64 seats and 16 percentage points also marked the largest loss of support for a sitting government since 1982. The opposition Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) obtained its worst result since the Spanish transition to democracy, losing 20 seats and nearly seven points. Newcomer Podemos (Spanish for "We can") ranked third, winning over five million votes, some 20% of the share, 69 seats and coming closely behind PSOE. Up-and-coming Citizens (C's), a party based in Catalonia since 2006, entered the parliament for the first time with 40 seats, though considerably lower than what pre-election polls had suggested.

Smaller parties were decimated, with historic United Left (IU)—which ran in a common platform with other left-wing parties under the Popular Unity umbrella—obtaining the worst result in its history. Union, Progress and Democracy (UPyD), a newcomer which had made gains in both the 2008 and 2011 general elections, was obliterated, losing all of its seats and nearly 90% of its votes. At the regional level, aside from a major breakthrough from Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC), the election saw all regional nationalist parties losing votes; the break up of Convergence and Union (CiU), support for the abertzale left EH Bildu coalition falling sharply, Canarian Coalition (CC) clinging on to a single seat and the expulsion of both Geroa Bai and the Galician Nationalist Bloc (BNG) from parliament; the latter of which had maintained an uninterrupted presence in the Congress of Deputies since 1996.

With the most-voted party obtaining just 123 seats—compared to the 156 of the previous worst result for a first party, in 1996—and a third party winning an unprecedented 69 seats—the previous record was 23 in 1979—the result marked the transition from a two-party system to a multi-party system. After months of inconclusive negotiations and a failed investiture, neither PP or PSOE were able to garner enough votes to secure a majority, leading to a fresh election in 2016.

Overview

Electoral system

The Spanish Cortes Generales were envisaged as an imperfect bicameral system. The Congress of Deputies had greater legislative power than the Senate, having the ability to vote confidence in or withdraw it from a prime minister and to override Senate vetoes by an absolute majority of votes. Nonetheless, the Senate possessed a few exclusive (yet limited in number) functions—such as its role in constitutional amendment—which were not subject to the Congress' override.[2][3] Voting for the Cortes Generales was on the basis of universal suffrage, which comprised all nationals over 18 years of age and in full enjoyment of their political rights. Additionally, Spaniards abroad were required to apply for voting before being permitted to vote, a system known as "begged" or expat vote (Spanish: Voto rogado).[4]

For the Congress of Deputies, 348 seats were elected using the D'Hondt method and a closed list proportional representation, with an electoral threshold of three percent of valid votes—which included blank ballots—being applied in each constituency. Seats were allocated to constituencies, corresponding to the provinces of Spain, with each being allocated an initial minimum of two seats and the remaining 248 being distributed in proportion to their populations. Ceuta and Melilla were allocated the two remaining seats, which were elected using plurality voting.[2][5] The use of the D'Hondt method might result in a higher effective threshold, depending on the district magnitude.[6]

As a result of the aforementioned allocation, each Congress multi-member constituency was entitled the following seats:[7]

| Seats | Constituencies |

|---|---|

| 36 | Madrid |

| 31 | Barcelona |

| 15 | Valencia(–1) |

| 12 | Alicante, Seville |

| 11 | Málaga(+1) |

| 10 | Murcia |

| 9 | Cádiz(+1) |

| 8 | A Coruña, Asturias, Balearic Islands, Biscay, Las Palmas |

| 7 | Granada, Pontevedra, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Zaragoza |

| 6 | Almería, Badajoz, Córdoba, Gipuzkoa, Girona, Tarragona, Toledo |

| 5 | Cantabria, Castellón, Ciudad Real, Huelva, Jaén(–1), León, Navarre, Valladolid |

| 4 | Álava, Albacete, Burgos, Cáceres, La Rioja, Lleida, Lugo, Ourense, Salamanca |

| 3 | Ávila, Cuenca, Guadalajara, Huesca, Palencia, Segovia, Teruel, Zamora |

| 2 | Soria |

For the Senate, 208 seats were elected using an open list partial block voting system, with electors voting for individual candidates instead of parties. In constituencies electing four seats, electors could vote for up to three candidates; in those with two or three seats, for up to two candidates; and for one candidate in single-member districts. Each of the 47 peninsular provinces was allocated four seats, whereas for insular provinces, such as the Balearic and Canary Islands, districts were the islands themselves, with the larger—Majorca, Gran Canaria and Tenerife—being allocated three seats each, and the smaller—Menorca, Ibiza–Formentera, Fuerteventura, La Gomera, El Hierro, Lanzarote and La Palma—one each. Ceuta and Melilla elected two seats each. Additionally, autonomous communities could appoint at least one senator each and were entitled to one additional senator per each million inhabitants.[2][5]

Election date

The term of each chamber of the Cortes Generales—the Congress and the Senate—expired four years from the date of their previous election, unless they were dissolved earlier. The election decree was required to be issued no later than the twenty-fifth day prior to the date of expiry of parliament and published on the following day in the Official State Gazette (BOE), with election day taking place on the fifty-fourth day from publication. The previous election was held on 20 November 2011, which meant that the legislature's term would expire on 20 November 2015. The election decree was required to be published in the BOE no later than 27 October 2015, with the election taking place on the fifty-fourth day from publication, setting the latest possible election date for the Cortes Generales on Sunday, 20 December 2015.[5]

The prime minister had the prerogative to dissolve both chambers at any given time—either jointly or separately—and call a snap election, provided that no motion of no confidence was in process, no state of emergency was in force and that dissolution did not occur before one year had elapsed since the previous one. Additionally, both chambers were to be dissolved and a new election called if an investiture process failed to elect a prime minister within a two-month period from the first ballot.[2] Barred this exception, there was no constitutional requirement for simultaneous elections for the Congress and the Senate. Still, as of 2024 there has been no precedent of separate elections taking place under the 1978 Constitution.

In May 2014, the Spanish newspaper ABC disclosed that the government was considering whether it was possible for a general election to be upheld until early 2016, supported on an ambiguous legal interpretation on the date of expiry of the Cortes Generales.[8] In September 2014, the Spanish media Voz Pópuli and El Plural further inquired on the possibility that the PP cabinet would be planning to delay the legislature's expiry by as much as possible, not holding a new election until February 2016.[9][10] However, legal reports commissioned by the government showed that the deadline for dissolving the Cortes and triggering a general election would be 26 October 2015, meaning that, with the election decree being published on the following day, an election could not be held later than 20 December. An opinion article published in Público on 8 December 2014 suggested that the probable date for the election would then be either on 25 October or on a Sunday in November 2015, not counting All Saints' Day.[11]

After the 2015 local and regional elections, it was suggested that the general election would presumably be held on either 22 or 29 November.[12][13] However, once it was confirmed that the government intended for the approval of the 2016 budget before the election, it was strongly implied that polling day would have to be delayed until December to allow for completion of the budgetary parliamentary procedure, with either 13 or 20 December being regarded as the only legally possible dates for an election to be held.[14] Finally, during an interview on 1 October, Rajoy announced that the election would be held on 20 December, the latest possible date allowed under Spanish law.[15] Being held 4 years and 1 month after the 2011 election, this was the longest time-span between two general elections since the Spanish transition to democracy.[1]

The Cortes Generales were officially dissolved on 27 October 2015 after the publication of the dissolution decree in the BOE, setting the election date for 20 December and scheduling for both chambers to reconvene on 13 January 2016.[7]

Background

Mariano Rajoy won the 2011 general election in a landslide running on a platform that promised to bring a solution to the country's worsening economic situation, marked by soaring unemployment and an out-of-control public deficit. However, shortly after taking office, Rajoy's People's Party (PP) popularity in opinion polls began to erode after its U-turn on economic policy, which included the breaching of many election pledges.[16]

In its first months in power, Rajoy's government approved a series of tax rises,[17] a harsh labour reform that allegedly cheapened dismissals[18]—and which was met with widespread protests and two general strikes in March and November 2012[19][20]—and an austere state budget for 2012.[21] The crash of Bankia, one of the largest banks of Spain, in May 2012 resulted in a dramatic rise of the Spanish risk premium, and in June the country's banking system needed a bailout from the IMF.[22][23] A major spending cut of €65 billion followed in July 2012, including a VAT rise from 18% to 21% which the PP itself had opposed during its time in opposition after the previous Socialist government had already raised VAT to 18%.[24][25] Additional spending cuts and legal reforms followed throughout 2012 and 2013, including cuts in budget credit lines for the health care and education systems, the implementation of a pharmaceutical copayment, a reform of the pension system which stopped guaranteeing the increase of pensioners' purchasing power accordingly to the consumer price index, the suppression of the bonus for public employees, or the withdrawal of public subsidies to the dependent people care system. Other measures, such as a fiscal amnesty in 2012 allowing tax evaders to regularize their situation by paying a 10% tax—later reduced to 3%—and no criminal penalty, had been previously rejected by the PP during its time in opposition.[26] Most of these measures were not included in the PP 2011 election manifesto and, inversely, many of the pledges included within were not fulfilled. Rajoy argued that "reality" prevented him from fulfilling his programme and that he had been forced to adapt to the new economic situation he found upon his accession to government.[27]

In the domestic field, the 2011–2015 period was dominated by a perceived regression in social and political rights. Spending cuts on the health care and education systems had fueled an increase in inequality among those without enough financial resources to afford those services.[28] The government's authorization of the enforcement and increase of court fees, requiring the payment of between €50 and €750 to appeal to the courts, was dubbed as violating the rights of effective judicial protection and free legal assistance. The controversial fees would later be removed in early 2015.[29][30] A new Education Law—the LOMCE—received heavy criticism from the Basque and Catalan regional governments, which dubbed it as a re-centralizer bill, as well as from social sectors which considered that it prompted segregation in primary schools. Another bill, the Citizen Security Law and dubbed the "gag law" by critics, was met with a global outcry because of it being seen as a cracking down on Spaniards' rights of freedom of assembly and expression, laying out strict guidelines on demonstrations—perceived to limit street protests—and steep fines to offenders.[31][32] Through 2013 to 2014, an attempt to amend the existing abortion law by a much stricter regulation allowing abortion only in cases of rape and of health risk to the mother[33][34] was thwarted due to public outrage and widespread criticism both from within and outside the PP itself,[35][36][37] resulting in its proponent, Justice Minister Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón, tendering his resignation.[38][39]

_(15).jpg.webp)

Political corruption became one of the focus issues for Spaniards in the polls after the Bárcenas affair erupted in early 2013, amid revelations that former PP treasurer Luis Bárcenas had used a slush fund to pay out monthly amounts to leading members of the party,[40][41] with further scandals rocking the PP for the remainder of its tenure. By late 2014, the sudden emergence of several episodes of corruption that had taken place over the previous years[42] was compared to the Italian Tangentopoli in the 1990s.[43] Among these were a massive expenses scandal involving former Caja Madrid senior executives and advisers—including members from the PP, PSOE and IU parties and from Spain's main trade unions, UGT and CCOO—, who were accused of using undeclared "black" credit cards for private expenditures;[44][45][46] revelations that the PP could have spent as much as €1.7 million of undeclared money on works on its national headquarters in Madrid between 2006 and 2008;[47] and the Punica case, a major scandal of public work contract kickbacks amounting at least €250 million and involving notable municipal and regional figures from both PSOE and PP, as well as a large number of politicians, councilors, officials and businessmen in the regions of Madrid, Murcia, Castile and León and Valencia.[48][49] Ongoing investigations on the Gürtel scandal on the illegal financing of both the Madrilenian and Valencian branches of the People's Party brought down Health Minister Ana Mato, who was suspect from having benefited of some of the crimes allegedly committed by her former husband Jesús Sepúlveda, charged in the Gürtel case.[50][51]

The Monarchy had also come under public scrutiny as a result of a corruption scandal affecting Duke of Palma Iñaki Urdangarín, the Nóos case, and his spouse Cristina de Borbón, Infanta of Spain and daughter of King Juan Carlos I, for possible crimes of tax fraud and money laundering.[53][54][55] These corruption allegations, coupled with other scandals—such as public anger at King Juan Carlos' elephant hunting trip to Botswana at the height of the economic crisis in 2012[56]—as well as his own health problems, had severely eroded the Spanish Royal Family's popularity among Spaniards,[57] and were said to have taken its toll on the monarch, who announced his abdication on his son Felipe—to become Felipe VI of Spain—in June 2014.[58]

The social response to the ongoing political and economic crisis was mixed. The 15-M Movement had resulted in an increase of street protests and demonstrations calling for a more democratic governmental system, a halt to spending cuts and tax increases and an overall rejection of Spain's two-party system formed by both PP and PSOE. Social mobilization channeled through various protest actions, such as "Surround the Congress" (Spanish for Rodea el Congreso), the so-called "Citizen Tides" (Mareas Ciudadanas) or the "Marches for Dignity" (Marchas de la Dignidad).[59][60][61] In Catalonia, the PP's rise to power and its perceived rightist stance were said to have been the final trigger for the independence movement to fire up. A 1.5-million strong demonstration in Barcelona on 11 September 2012 finally convinced the regional ruling Convergence and Union (CiU) of Artur Mas to switch to independence support, with a snap election being held in November 2012 resulting in a huge rise for pro-independence ERC and the CUP and a meltdown for Socialist support in the region. Finally, the PP decline and the PSOE inability to recover lost support paved the way for the rise of new parties in the national landscape, such as Podemos and Citizens (C's), which began to rise dramatically in opinion polls after 2014 European Parliament election. PSOE leader Alfredo Pérez Rubalcaba resigned the day after the European election,[62] being succeeded by Pedro Sánchez after a party leadership election in July 2014.[63]

Parliamentary composition

The tables below show the composition of the parliamentary groups in both chambers at the time of dissolution.[64][65]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Parties and candidates

The electoral law allowed for parties and federations registered in the interior ministry, coalitions and groupings of electors to present lists of candidates. Parties and federations intending to form a coalition ahead of an election were required to inform the relevant Electoral Commission within ten days of the election call, whereas groupings of electors needed to secure the signature of at least one percent of the electorate in the constituencies for which they sought election, disallowing electors from signing for more than one list of candidates. Concurrently, parties, federations or coalitions that had not obtained a mandate in either chamber of the Cortes at the preceding election were required to secure the signature of at least 0.1 percent of electors in the aforementioned constituencies.[5]

Below is a list of the main parties and electoral alliances which contested the election:

The People's Party (PP) chose to continue its electoral alliance with the Aragonese Party (PAR) under which it had already won the general election in Aragon in 2011.[78] In Asturias, an alliance with Asturias Forum (FAC)—former PP member Francisco Álvarez Cascos's party—was reached. Hastened by FAC's vote collapsing in the 2015 Asturian regional election, this was the first time both parties contested an election together since Cascos's party split in 2011.[79] An agreement with Navarrese People's Union (UPN) was also reached, after a period of negotiations in which the regional party had considered to contest the general election on its own in Navarre.[80] For the Senate, the PP also aligned itself with the Fuerteventura Municipal Assemblies (AMF) to contest the election in the Senate district of Fuerteventura.[81]

Meanwhile, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) and New Canaries (NCa) both announced they would contest the general election together in the Canary Islands. NCa had already contested the 2008 and 2011 elections before: in 2008 they stood alone and won no seats, while in 2011 they won 1 seat as a result of an alliance with Canarian Coalition (CCa), alliance which they chose not to continue in 2015.[82] Extremaduran Coalition and United Extremadura broke up their coalitions with both PSOE and PP, respectively, and chose to contest the general together under a single joint list, Extremeños (Spanish for "Extremadurans").[83]

In order to contest the general election, Podemos set up an extensive alliance system in several autonomous communities with other parties. After the negative results of the Catalunya Sí que es Pot alliance in the September Catalan election, Podemos, Initiative for Catalonia Greens (ICV) and United and Alternative Left (EUiA) reached an agreement with Barcelona en Comú—Barcelona Mayor Ada Colau's party—to form a joint list to contest the general election in Catalonia: En Comú Podem (Catalan for In Common We Can). The coalition was aimed at mirroring Colau's success in the 2015 Barcelona City Council election at Catalan level;[84] if successful, it was planned to be maintained permanently for future electoral contests.[85] In Galicia, Podemos, Anova and United Left (EU) merged into the En Marea ticket (Galician for In Tide). Such a coalition, which represented a qualitative leap from the Galician Left Alternative (AGE) coalition in the 2012 Galician regional election, was aimed at channeling the results of the local "mareas" ("tides") that succeeded throughout Galicia's largest cities in the May local elections. The coalition also received support from those local alliances, such as Marea Atlántica, Compostela Aberta or Ferrol en Común.[86]

For the Valencian Community, the És el moment alliance (Valencian for It is Time) was created as a result of the agreement between Podemos and Compromís, with a strong role from Valencian deputy premier Mònica Oltra.[87][88] United Left of the Valencian Country (EUPV) had also entered talks to enter the alliance, but left after disagreements with both Podemos and Compromís during negotiations.[89] Additionally, Podemos was to contest the general election in the province of Huesca alongside segments of Now in Common within the "Ahora Alto Aragón en Común" coalition (Spanish for Now Upper Aragon in Common).[90] In Navarre, all four Podemos, Geroa Bai, EH Bildu and I-E coalesced under the Cambio-Aldaketa umbrella for the Senate, aiming at disputing first place regionally to the UPN–PP alliance. The agreement was not extended to the Congress election, where all four parties ran separately.[76][77]

In Catalonia and Galicia, Popular Unity (IU–UPeC) did not contest the election as such. The respective regional United Left branches joined En Marea and En Comú Podem, which supported Podemos at the national level. While a nationwide coalition between Podemos and IU had been considered, Podemos did not wish to assume IU's internal issues, and United Left candidate Alberto Garzón had refused to leave IU to integrate Podemos' lists.[91] On the other hand, environmentalist party Equo was successful at reaching an agreement with Podemos, accepting to renounce their label and integrating themselves within Podemos' lists.[92]

After the dissolution of the Convergence and Union (CiU) federation in Catalonia, Democratic Convergence of Catalonia (CDC) joined Democrats of Catalonia and Reagrupament within the Democracy and Freedom alliance after the failure of talks with Republican Left of Catalonia to continue the Junts pel Sí coalition for the general election.[93][94] CDC's former ally, Josep Antoni Duran i Lleida's Democratic Union of Catalonia (UDC), chose to contest the election alone despite losing its parliamentary presence in the Parliament of Catalonia after the 2015 regional election.[95]

Timetable

The key dates are listed below (all times are CET. The Canary Islands used WET (UTC+0) instead):[5][96][97]

- 26 October: The election decree is issued with the countersign of the Prime Minister after deliberation in the Council of Ministers, ratified by the King.[7]

- 27 October: Formal dissolution of the Cortes Generales and official start of ban period for the organization of events for the inauguration of public works, services or projects.

- 30 October: Initial constitution of provincial and zone electoral commissions.

- 6 November: Deadline for parties and federations intending to enter in coalition to inform the relevant electoral commission.

- 16 November: Deadline for parties, federations, coalitions and groupings of electors to present lists of candidates to the relevant electoral commission.

- 18 November: Submitted lists of candidates are provisionally published in the Official State Gazette (BOE).

- 21 November: Deadline for citizens entered in the Register of Absent Electors Residing Abroad (CERA) and for citizens temporarily absent from Spain to apply for voting.

- 22 November: Deadline for parties, federations, coalitions and groupings of electors to rectify irregularities in their lists.

- 23 November: Official proclamation of valid submitted lists of candidates.

- 24 November: Proclaimed lists are published in the BOE.

- 4 December: Official start of electoral campaigning.[7]

- 10 December: Deadline to apply for postal voting.

- 15 December: Official start of legal ban on electoral opinion polling publication, dissemination or reproduction and deadline for CERA citizens to vote by mail.

- 16 December: Deadline for postal and temporarily absent voters to issue their votes.

- 18 December: Last day of official electoral campaigning and deadline for CERA citizens to vote in a ballot box in the relevant consular office or division.[7]

- 19 December: Official 24-hour ban on political campaigning prior to the general election (reflection day).

- 20 December: Polling day (polling stations open at 9 am and close at 8 pm or once voters present in a queue at/outside the polling station at 8 pm have cast their vote). Counting of votes starts immediately.

- 23 December: General counting of votes, including the counting of CERA votes.

- 26 December: Deadline for the general counting of votes to be carried out by the relevant electoral commission.

- 4 January: Deadline for elected members to be proclaimed by the relevant electoral commission.

- 14 January: Deadline for both chambers of the Cortes Generales to be re-assembled (the election decree determines this date, which for the 2015 election was set for 13 January).[7]

- 13 February: Maximum deadline for definitive results to be published in the BOE.

Campaign

Party slogans

| Party or alliance | Original slogan | English translation | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | « España en serio » | "Spain seriously" | [98][99][100] | |

| PSOE | « Un futuro/un presidente para la mayoría » | "A future/a president for the many" | [98][99][100][101] | |

| DiL | « |

" |

[98][99][100][102] | |

| unio.cat | « Solucions! » | "Solutions!" | [98][99][103] | |

| IU–UPeC | « Por un nuevo país » | "For a new country" | [98][99][100] | |

| EH Bildu | « Bildu erabakira » « Únete a la decisión » |

"Join the decision" | [98][104] | |

| EAJ/PNV | « Lehenik Euskadi. Euskadi es lo que importa » | "The Basque Country first. The Basque Country is what matters" | [98][99][104] | |

| UPyD | « Más España » | "More Spain" | [98][99] | |

| ERC–CatSí | « Defensa el teu vot » | "Defend your vote" | [98][99] | |

| Nós | « A forza do noso pobo » | "The strength of our people" | [98] | |

| CCa–PNC | « Luchar por Canarias » | "Fighting for the Canaries" | [98] | |

| GBai | « Defiende Navarra. Nafarron Hitza Madrilen » | "Defend Navarre. The voice of the Navarrese people in Madrid" | [105][106] | |

| Podemos | Main: « Un país contigo. Podemos » En Comú: « El canvi no s'atura » És el moment: « Justament és el moment » En Marea: « Para mudalo todo, para que nada siga igual » |

Main: "A country with you. We Can" En Comú: "The change does not stop" És el moment: "It is precisely the time" En Marea: "To change everything, so that nothing remains the same" |

[98][99][100][107] [108] [109] [110] | |

| C's | « Con ilusión » | "With hope" | [98][99][100] | |

Election debates

A total of four debates involving the leaders of at least two of the four parties topping opinion polls (PP, PSOE, Podemos and C's) were held throughout the pre-campaign and campaign periods.

The first debate was organized by the Demos Association and held in the Charles III University of Madrid on 27 November. The leaders of the four main parties were invited, but in the end only Pablo Iglesias and Albert Rivera attended.[111] The debate was broadcast live on YouTube.[112]

The second debate was held on 30 November. Organized by El País newspaper, it was broadcast live entirely through the websites of El País and Cinco Días, the Cadena SER radio station and on the 13 TV television channel. Pedro Sánchez, as well as Iglesias and Rivera, attended the debate. Mariano Rajoy (PP) was also invited to the debate but declined the offer.[113][114] According to the organizer, PP proposed the presence of Deputy PM Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría instead but it was refused, as she "was not the PP candidate for PM".[115] A poll conducted online immediately after the debate by El País to its readers showed Iglesias winning with 47.0%, followed by Rivera with 28.9% and Sánchez with 24.1%.[116]

A third, televised debate was organized by Atresmedia, held on 7 December and broadcast live simultaneously on its Antena 3 and laSexta TV channels and on the Onda Cero radio station. Rajoy had also been invited to the debate, but the PP announced that Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría would attend in his place instead.[117] The audience for the debate averaged 9.2 million, peaking at more than 10 million.[118] Online polls conducted immediately after the debate by major newspapers coincided in showing Iglesias winning,[119] while political pundits and journalists pointed on his strong performance.[120][121][122]

A fourth, final debate, organized by the TV Academy, was held on 14 December. The signal of the debate was offered to all interested media. Among others, nationwide TV channels La 1, Canal 24 Horas, Antena 3, laSexta and 13 TV broadcast the debate live.[123] Iglesias and Rivera were not invited to the debate, with only Rajoy and Sánchez participating.[124] The audience for the debate averaged 9.7 million.[125] A poll conducted by Atresmedia immediately after the debate showed 34.5% saying that "None of them" won, followed by Sánchez with 33.7%, Rajoy with 28.8% and "Both" with 3.0%.[126]

| Date | Organisers | Moderator(s) | P Present[lower-alpha 13] S Surrogate[lower-alpha 14] NI Not invited A Absent invitee | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | PSOE | IU–UPeC | UPyD | Podemos | C's | DiL | unio.cat | PNV | Audience | Ref. | |||

| 18 October | laSexta (Salvados) |

Jordi Évole | A | A | NI | NI | P Iglesias |

P Rivera |

NI | NI | NI | 25.2% (5,214,000) |

[127] |

| 21 November | Cuatro (Un Tiempo Nuevo) |

Silvia Intxaurrondo | S Maroto |

S López |

S Sixto |

P Herzog |

S Errejón |

S Girauta |

NI | NI | NI | 3.2% (449,000) |

[128] |

| 26 November | Ángel Carmona | S Maroto |

S González |

S Sánchez |

P Herzog |

S Errejón |

S De Páramo |

NI | NI | NI | — | [129] | |

| 27 November | UC3M | Carlos Alsina | A | A | NI | NI | P Iglesias |

P Rivera |

NI | NI | NI | — | [130] |

| 30 November | El País | Carlos de Vega | A | P Sánchez |

NI | NI | P Iglesias |

P Rivera |

NI | NI | NI | — | [131] |

| 6 December | laSexta (El Objetivo)[lower-alpha 15] |

Ana Pastor | P Casado |

P Saura |

P Garzón |

NI | P Álvarez |

P Garicano |

NI | NI | NI | 7.2% (1,268,000) |

[132] |

| 7 December | Atresmedia | Ana Pastor Vicente Vallés |

S Santamaría |

P Sánchez |

NI | NI | P Iglesias |

P Rivera |

NI | NI | NI | 48.2% (9,233,000) |

[133] |

| 9 December | TVE (El debate de La 1) |

Julio Somoano | S Casado |

S Hernando |

P Garzón |

P Herzog |

S Errejón |

S De la Cruz |

S Puig |

S Surroca |

P Esteban |

12.1% (2,342,000) |

[134] |

| 14 December | TV Academy | Manuel Campo Vidal | P Rajoy |

P Sánchez |

NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | NI | 48.7% (9,728,000) |

[135] |

- Opinion polls

| Debate | Polling firm/Commissioner | PP | PSOE | Pod. | C's | Tie | None | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 November | El País[136] | 24.1 | 47.0 | 28.9 | – | – | – | |

| 7 December | Redondo & Asociados[137] | 30.7 | 16.4 | 23.9 | 22.0 | – | – | 7.0 |

| CIS[138] | 18.3 | 8.9 | 31.3 | 12.0 | 2.7 | 16.2 | 10.6 | |

| 14 December | Atresmedia[139] | 28.8 | 33.7 | 3.0 | 34.5 | – | ||

| CIS[138] | 26.1 | 26.9 | 3.5 | 37.1 | 6.4 | |||

Development

Opinion polls heading into the campaign had shown the PP firmly in first position, with both PSOE and C's tied for second place and Podemos trailing in fourth. However, as the campaign started and election day neared, Podemos numbers had begun to rebound while C's slipped. Podemos centered its campaign around the slogan of "remontada" (Spanish for "comeback"), trying to convey voters a message of illusion and optimism.[140] After the Atresmedia televised debate on 7 December—in which Iglesias was said to have outperformed all other three with his final address[141]—and following a series of gaffes by C's leaders that had affected their party's campaign,[142] Podemos experienced a surge in opinion polls. By Monday 14 December it had reached a statistical tie with C's, and kept growing and approaching the PSOE, vying for second place, in the polls conducted—but unpublished by Spanish media—after the legal ban on opinion polls during the last week of campaigning had entered into force.[143] On 18 December, the final day of campaigning, Podemos staged a massive rally in la Fonteta arena in Valencia, in support of the Compromís–Podemos–És el moment coalition and as the closing point of their campaign. With a capacity of over 9,000 people, 2,000 were left outside as the interior was entirely filled.[144][145] It was noted by some media as a remarkable feat, as the PSOE had been unable to entirely fill the same place just a few days earlier on 13 December.[146]

The most notable incident during the electoral campaign was an attack on Mariano Rajoy during a campaign event in Pontevedra on 16 December. At 18:50, while walking with Development Minister Ana Pastor in the vicinity of the Pilgrim Church, a 17-year-old approached him and punched him in the temple. The assailant was restrained by the Prime Minister's security guards and was subsequently transferred to the police station in the city. Rajoy, who was red-faced and stunned for a few seconds, continued to walk without his glasses, broken during the assault.[147][148] The assailant turned out to be related to Rajoy's wife, as he was the son of a cousin of Elvira Fernández, and also a member of a family known for sympathizing with the People's Party.[149]

The following day, Rajoy attended a European Council meeting in Brussels, where Angela Merkel and other European leaders approached him showing their support to him after the assault.[150] During the meeting a camera recorded Rajoy, Merkel and other leaders discussing the electoral prospects of Spanish parties. Rajoy revealed to them that, according to PP internal opinion polls, Podemos was rising quickly and approaching the PSOE, to the point that there was the possibility of it becoming the second political force of the country. Merkel expressed concern about such an event.[151]

Opinion polls

Results

Congress of Deputies

| ||||||

| Parties and alliances | Popular vote | Seats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | ±pp | Total | +/− | ||

| People's Party (PP)1 | 7,236,965 | 28.71 | –16.33 | 123 | –64 | |

| Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) | 5,545,315 | 22.00 | –6.76 | 90 | –20 | |

| We Can–In Common–Commitment–In Tide (Podemos) | 5,212,711 | 20.68 | New | 69 | +65 | |

| In Tide (Podemos–Anova–EU)5 | 410,698 | 1.63 | +1.31 | 6 | +6 | |

| Citizens–Party of the Citizenry (C's) | 3,514,528 | 13.94 | New | 40 | +40 | |

| United Left–Popular Unity in Common (IU–UPeC)6 | 926,783 | 3.68 | –1.81 | 2 | –6 | |

| Republican Left of Catalonia–Catalonia Yes (ERC–CatSí) | 604,285 | 2.40 | +1.34 | 9 | +6 | |

| Valencian Country Now (Ara PV)7 | 2,503 | 0.01 | –0.02 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Democracy and Freedom (DiL)8 | 567,253 | 2.25 | –1.92 | 8 | –8 | |

| Basque Nationalist Party (EAJ/PNV) | 302,316 | 1.20 | –0.13 | 6 | +1 | |

| Animalist Party Against Mistreatment of Animals (PACMA) | 220,369 | 0.87 | +0.45 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Basque Country Gather (EH Bildu)9 | 219,125 | 0.87 | –0.50 | 2 | –5 | |

| Union, Progress and Democracy (UPyD) | 155,153 | 0.62 | –4.08 | 0 | –5 | |

| Canarian Coalition–Canarian Nationalist Party (CCa–PNC)10 | 81,917 | 0.32 | –0.27 | 1 | –1 | |

| We–Galician Candidacy (Nós)11 | 70,863 | 0.28 | –0.48 | 0 | –2 | |

| Democratic Union of Catalonia (unio.cat) | 65,388 | 0.26 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Vox (Vox) | 58,114 | 0.23 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Zero Cuts–Green Group (Recortes Cero–GV) | 48,675 | 0.19 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| More for the Balearic Islands (Més)12 | 33,877 | 0.13 | ±0.00 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Communist Party of the Peoples of Spain (PCPE) | 31,179 | 0.12 | +0.01 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Yes to the Future (GBai) | 30,642 | 0.12 | –0.05 | 0 | –1 | |

| El Pi–Proposal for the Isles (El Pi) | 12,910 | 0.05 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Citizens of Democratic Centre (CCD) | 10,827 | 0.04 | +0.04 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Blank Seats (EB) | 10,084 | 0.04 | –0.36 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Spanish Phalanx of the CNSO (FE–JONS) | 7,495 | 0.03 | +0.02 | 0 | ±0 | |

| For the Left–The Greens (X Izda) | 7,314 | 0.03 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| We Are Valencian (SOMVAL) | 6,103 | 0.02 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| For a Fairer World (PUM+J) | 4,586 | 0.02 | –0.09 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Internationalist Solidarity and Self-Management (SAIn) | 4,400 | 0.02 | –0.01 | 0 | ±0 | |

| The Eco-pacifist Greens (Centro Moderado) | 3,278 | 0.01 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Land Party (PT) | 3,026 | 0.01 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Canaries Decides (LV–UP–ALTER)13 | 2,883 | 0.01 | +0.01 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Libertarian Party (P–LIB) | 2,854 | 0.01 | ±0.00 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Humanist Party (PH) | 2,846 | 0.01 | –0.03 | 0 | ±0 | |

| United Extremadura–Extremadurans (EU–eX)14 | 2,021 | 0.01 | +0.01 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Spanish Communist Workers' Party (PCOE) | 1,909 | 0.01 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| National Democracy (DN) | 1,704 | 0.01 | ±0.00 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Feminist Initiative (IFem) | 1,604 | 0.01 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Regionalist Party of the Leonese Country (PREPAL) | 1,419 | 0.01 | ±0.00 | 0 | ±0 | |

| In Positive (En Positiu) | 1,276 | 0.01 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| United Free Citizens (CILUS) | 1,189 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Grouped Rural Citizens (CRA) | 1,032 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Navarrese Freedom (Ln) | 1,026 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Forward Valencians (Avant) | 1,003 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Málaga for Yes (mlgXSÍ) | 934 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Family and Life Party (PFyV) | 714 | 0.00 | ±0.00 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Andalusians of Jaén United (AJU) | 711 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Independents for Aragon (i) | 676 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Democratic Forum (FDEE) | 456 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| To Solution (Soluciona) | 409 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Social Justice, Citizen Participation (JS,PC) | 406 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Death to the System (+MAS+) | 313 | 0.00 | ±0.00 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Liberal Party of the Right (PLD) | 205 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Welcome (Ongi Etorri) | 110 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Blank ballots | 188,132 | 0.75 | –0.62 | |||

| Total | 25,211,313 | 350 | ±0 | |||

| Valid votes | 25,211,313 | 99.11 | +0.40 | |||

| Invalid votes | 227,219 | 0.89 | –0.40 | |||

| Votes cast / turnout | 25,438,532 | 69.67 | +0.73 | |||

| Abstentions | 11,073,316 | 30.33 | –0.73 | |||

| Registered voters | 36,511,848 | |||||

| Sources[152][153] | ||||||

Footnotes:

| ||||||

Senate

| ||||||

| Parties and alliances | Popular vote | Seats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | ±pp | Total | +/− | ||

| People's Party (PP)1 | 20,105,650 | 30.31 | –16.45 | 124 | –12 | |

| Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE)2 | 14,887,751 | 22.44 | –3.53 | 47 | –7 | |

| We Can–In Common–Commitment–In Tide (Podemos) | 12,244,416 | 18.46 | New | 16 | +15 | |

| In Tide (Podemos–Anova–EU)6 | 992,696 | 1.50 | +1.26 | 2 | +2 | |

| Citizens–Party of the Citizenry (C's) | 7,417,388 | 11.18 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| United Left–Popular Unity in Common (IU–UPeC)7 | 2,372,637 | 3.58 | –1.28 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Republican Left–Catalonia Yes (ERC–CatSí) | 1,895,501 | 2.86 | +1.81 | 6 | +6 | |

| Valencian Country Now (Ara PV)8 | 7,888 | 0.01 | –0.01 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Democracy and Freedom (DiL)9 | 1,531,259 | 2.31 | –1.78 | 6 | –3 | |

| Animalist Party Against Mistreatment of Animals (PACMA) | 1,036,736 | 1.56 | +0.97 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Basque Nationalist Party (EAJ/PNV) | 907,267 | 1.37 | –0.09 | 6 | +2 | |

| Union, Progress and Democracy (UPyD) | 620,704 | 0.94 | –0.73 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Basque Country Gather (EH Bildu)10 | 564,575 | 0.85 | –0.43 | 0 | –3 | |

| Change (Cambio/Aldaketa)11 | 282,889 | 0.43 | –0.02 | 1 | +1 | |

| We–Galician Candidacy (Nós)12 | 279,325 | 0.42 | –0.52 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Vox (Vox) | 196,457 | 0.30 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Zero Cuts–Green Group (Recortes Cero–GV) | 174,481 | 0.26 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Canarian Coalition–Canarian Nationalist Party (CCa–PNC)13 | 156,636 | 0.24 | –0.18 | 1 | ±0 | |

| Democratic Union of Catalonia (unio.cat) | 154,702 | 0.23 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Communist Party of the Peoples of Spain (PCPE) | 105,250 | 0.16 | +0.04 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Blank Seats (EB) | 88,802 | 0.13 | –0.69 | 0 | ±0 | |

| More for Mallorca (Més)14 | 60,527 | 0.09 | +0.01 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Spanish Phalanx of the CNSO (FE–JONS) | 37,688 | 0.06 | +0.04 | 0 | ±0 | |

| El Pi–Proposal for the Isles (El Pi) | 30,557 | 0.05 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| For a Fairer World (PUM+J) | 20,187 | 0.03 | –0.12 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Citizens of Democratic Centre (CCD) | 20,150 | 0.03 | +0.03 | 0 | ±0 | |

| We Are Valencian (SOMVAL) | 19,950 | 0.03 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Internationalist Solidarity and Self-Management (SAIn) | 18,377 | 0.03 | –0.01 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Land Party (PT) | 10,128 | 0.02 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| United Extremadura–Extremadurans (EU–eX)15 | 10,065 | 0.01 | ±0.00 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Regionalist Party of the Leonese Country (PREPAL) | 9,905 | 0.01 | ±0.00 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Humanist Party (PH) | 9,789 | 0.01 | –0.05 | 0 | ±0 | |

| The Eco-pacifist Greens (Centro Moderado) | 9,440 | 0.01 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Libertarian Party (P–LIB) | 7,777 | 0.01 | ±0.00 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Canaries Decides (LV–UP–ALTER)16 | 6,337 | 0.01 | ±0.00 | 0 | ±0 | |

| United for Gran Canaria (UxGC) | 5,885 | 0.01 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Navarrese Freedom (Ln) | 5,710 | 0.01 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Feminist Initiative (IFem) | 5,623 | 0.01 | +0.01 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Forward Valencians (Avant) | 4,948 | 0.01 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| In Positive (En Positiu) | 4,548 | 0.01 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| National Democracy (DN) | 4,456 | 0.01 | ±0.00 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Gomera Socialist Group (ASG) | 4,435 | 0.01 | New | 1 | +1 | |

| We Are Menorca (Som Menorca)17 | 4,129 | 0.01 | +0.01 | 0 | ±0 | |

| Forward Badajoz (BA) | 4,025 | 0.01 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| United Free Citizens (CILUS) | 3,140 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Independents for Aragon (i) | 2,716 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Andalusians of Jaén United (AJU) | 1,836 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Grouped Rural Citizens (CRA) | 1,624 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| To Solution (Soluciona) | 1,573 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Family and Life Party (PFyV) | 1,569 | 0.00 | ±0.00 | 0 | ±0 | |

| We (Nosotros) | 1,472 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Social Justice, Citizen Participation (JS,PC) | 1,399 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Merindades of Castile Initiative (IMC) | 1,225 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Democratic Forum (FDEE) | 1,222 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Aragonese Bloc (BAR) | 1,183 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| For the Left–The Greens (X Izda) | 1,009 | 0.00 | New | 0 | ±0 | |

| Blank ballots[lower-alpha 16] | 979,371 | 4.06 | –1.30 | |||

| Total | 66,336,401 | 208 | ±0 | |||

| Valid votes | 24,119,913 | 96.78 | +0.48 | |||

| Invalid votes | 801,743 | 3.22 | –0.48 | |||

| Votes cast / turnout | 24,921,656 | 68.26 | –0.17 | |||

| Abstentions | 11,590,192 | 31.74 | +0.17 | |||

| Registered voters | 36,511,848 | |||||

| Sources[65][152][153][154] | ||||||

Footnotes:

| ||||||

Aftermath

Outcome

The election results produced the most fragmented parliament in recent Spanish history. As opinion polls had predicted, the People's Party (PP) was able to secure first place with a clear lead over its rivals, but it lost the absolute majority it had held since 2011 in the Congress of Deputies. Its 123 seat-count was the worst result ever obtained by a winning party in a Spanish general election—previously been 156 seats in 1996. Its result was also slightly below the party's expected goal of reaching 30% of the vote.[155] The party's net loss of seats (64 fewer than in 2011) and vote share drop (minus 16 percentage points) was the PP's largest fall in popular support in its history, as well as the worst showing for a sitting government in Spain since 1982. Overall, it was also the worst result obtained by the PP in a general election since 1989, back to the party's refoundation from the People's Alliance.

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) obtained its worst election result in recent history, with just 22% of the total party vote and 90 seats, well below Pedro Sánchez's target of at least 100 seats.[156] Losing 20 seats and nearly 7 percentage points to its already negative 2011 result, this was the first time since the Spanish transition to democracy that one of the two largest parties fell below the 100-seat mark. Overall, while able to hold on to its second place nationally in terms of votes and seats, it lost the second and first place to Podemos in 8 out of the 17 autonomous communities, and finished fourth in Madrid, the capital's district. It was able to narrowly win in Andalusia and Extremadura—which it had resoundingly lost to the PP in 2011—thanks to the PP vote collapse in those regions, but it lost in Barcelona for the first time ever in a general election, and its sister party, the Socialists' Party of Catalonia (PSC), was reduced to third party status in Catalonia after decades of political dominance.

The combined results for the top two parties was also the worst for any general election held since 1977, gathering just 51% of the total party vote and 213 seats, just slightly above the required 3/5 majority for an ordinary constitutional reform. The result was regarded as a loss for bipartisanship in Spain as a whole, as the era of bipartisan politics was declared officially over by newcomers Podemos and Citizens, as well as by both national and international media.[157][158][159]

Podemos, which contested a general election for the first time after having been founded in January 2014, obtained an unprecedented 21% of the vote and 69 seats together with its regional alliances, the best result ever obtained by a third party in a Spanish election. Coming short by 340,000 votes of securing its campaign goal of becoming the main left-wing party in Spain, it managed to secure second place in 6 out of the 17 autonomous communities and came top in another two—the Basque Country and Catalonia. This result was ahead of what initial pre-campaign and campaign opinion polls had predicted, and was in line with a late-campaign surge in support for the party. Citizens (C's) also had a strong performance for a national party in Spain, but its fourth place, 14% of the share and 40 seats were considered a letdown for party leader Albert Rivera, mainly as a consequence of the high expectations that had been generated around his candidacy. Pre-election opinion polls had placed C's near or above 20% of the vote share, and many also suggested a strong possibility of C's disputing second place to PSOE. Finally, it only came ahead of either PSOE or PP in Madrid and Catalonia.[160][161] The party also found itself in a weaker political position than predicted, as the "kingmaker" position that was thought to go to C's under opinion polling projections finally went to PSOE, with the Congress' fragmentation resulting from the election meaning that neither the PP–C's nor the PSOE–Podemos–IU blocs would be able to command a majority on their own.

Government formation

| Investiture Pedro Sánchez (PSOE) | |||

| Ballot → | 2 March 2016 | 4 March 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Required majority → | 176 out of 350 |

Simple | |

130 / 350 |

131 / 350 | ||

219 / 350 |

219 / 350 | ||

Abstentions

|

1 / 350 |

0 / 350 | |

| Absentees | 0 / 350 |

0 / 350 | |

| Sources[162] | |||

Notes

- ↑ Total figures include results for En Comú Podem, És el moment and En Marea.

- 1 2 Results for PP (44.63%, 186 deputies and 136 senators) and FAC (0.41%, 1 deputy and 0 senators) in the 2011 election.

- 1 2 ICV–EUiA (3 deputies and 1 senator), which contested the 2011 election within the IU–LV and Entesa alliances, joined the En Comú Podem alliance ahead of the 2015 election. Compromís (1 deputy) joined the És el moment alliance.

- 1 2 Results for CiU in the 2015 election.

- ↑ 1 UPyD seat was vacant as a result of Irene Lozano's resignation to join the PSOE on 16 October 2015.[67]

- ↑ 1 PP appointed seat remained vacant until 14 December 2016.[69]

- ↑ Juan Morano, former PP legislator.[70]

- ↑ Including results for PSC–PSOE, which contested the 2011 Senate election within the Entesa alliance.

- ↑ Results for IU–LV in the 2011 election, not including ICV–EUiA.

- ↑ Results for Amaiur in the 2011 election.

- 1 2 3 EH Bildu (0 senators), GBai (0 senators), Podemos (0 senators) and I–E (n) (0 senators) joined the Cambio/Aldaketa alliance ahead of the 2015 Senate election in Navarre.

- ↑ Results for BNG in the 2011 election.

- ↑ Denotes a main invitee attending the event.

- ↑ Denotes a main invitee not attending the event, sending a surrogate in their place.

- ↑ Economic debate.

- ↑ The percentage of blank ballots is calculated over the official number of valid votes cast, irrespective of the total number of votes shown as a result of adding up the individual results for each party.

References

- 1 2 Jiménez Gálvez, José María (1 October 2015). "Rajoy fija el periodo más largo de la democracia sin elecciones generales". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Constitución Española". Constitution of 29 December 1978 (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ↑ "Constitución española, Sinopsis artículo 66". Congress of Deputies (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ↑ Reig Pellicer, Naiara (16 December 2015). "Spanish elections: Begging for the right to vote". cafebabel.co.uk. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Ley Orgánica 5/1985, de 19 de junio, del Régimen Electoral General". Organic Law No. 5 of 19 June 1985 (in Spanish). Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ↑ Gallagher, Michael (30 July 2012). "Effective threshold in electoral systems". Trinity College, Dublin. Archived from the original on 30 July 2017. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Real Decreto 977/2015, de 26 de octubre, de disolución del Congreso de los Diputados y del Senado y de convocatoria de elecciones" (PDF). Boletín Oficial del Estado (in Spanish) (257): 100784–100786. 27 October 2015. ISSN 0212-033X.

- ↑ Alcáraz, Mayte (13 May 2014). "Rajoy estudia agotar el plazo legal para que las elecciones sean en 2016". ABC (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ Maqueda, Antonio (22 September 2014). "El PP se plantea retrasar las elecciones hasta febrero de 2016 a la espera de una recuperación más fuerte y estable". Voz Pópuli (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "La vicepresidenta encarga informes jurídicos para retrasar las elecciones generales a 2016". El Plural (in Spanish). 22 September 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ Sánchez, Manuel (8 December 2014). "A once meses de las elecciones generales... o menos". Público (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "Rajoy maneja los días 22 ó 29 de noviembre para las elecciones generales". Madrid: Europa Press. 27 May 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "Rajoy planea convocar las elecciones generales el 22 o 29 de noviembre". El Periódico de Catalunya. Madrid. 27 May 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "La aprobación de los Presupuestos lleva las elecciones generales hasta el 13 de diciembre". Libertad Digital (in Spanish). 4 August 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ Casqueiro, Javier (1 October 2015). "Rajoy anuncia que las elecciones generales serán el 20 de diciembre". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ Castro, Irene (19 November 2013). "Diez incumplimientos electorales de Mariano Rajoy". eldiario.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Elordi Cué, Carlos (31 December 2011). "Rajoy aprueba el mayor recorte de la historia y una gran subida de impuestos". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Gómez, Manuel Vicente (10 February 2012). "La reforma facilita y abarata el despido". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "El 29 de marzo, huelga general". El Mundo (in Spanish). Madrid. Agencias. 9 March 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Doncel, Luis; Gómez, Manuel Vicente (17 October 2012). "Los sindicatos convocarán una huelga general para el 14 de noviembre". El País (in Spanish). Brussels / Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "El Gobierno presenta los presupuestos generales con un recorte de 27.300 millones". 20 minutos (in Spanish). Agencias. 30 March 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Jiménez, Miguel; Pozzi, Sandro (9 June 2012). "El FMI adelanta el informe que aboca a España al rescate bancario". El País (in Spanish). Madrid / New York. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Gragera de León, Flor (24 July 2012). "Los pasos hacia el escándalo de Bankia". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ González, Jesús Sérvulo (11 July 2012). "El ajuste más duro de la democracia". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "El Gobierno aprueba quitar la paga extra esta Navidad a los funcionarios y la subida del IVA". 20 minutos (in Spanish). 13 July 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Jiménez, Miguel (4 June 2012). "Las 15 preguntas clave sobre la amnistía fiscal del Gobierno". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "Dos años de Gobierno de Rajoy: recortes no anunciados y leyes que no estaban en el guión". 20 minutos (in Spanish). 21 December 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Martínez, Silvia (18 March 2015). "Europa alerta de que los recortes podan derechos en España". El Periódico de Catalunya (in Spanish). Brussels. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "Gallardón defiende las tasas judiciales porque "van a garantizar más la justicia gratuita"". ABC (in Spanish). Madrid. Agencias. 23 November 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Blanco, Teresa (27 February 2015). "El Gobierno elimina para las personas físicas el polémico 'tasazo' de Gallardón". El Economista (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Kassam, Ashifa (12 March 2015). "Spain puts 'gag' on freedom of expression as senate approves security law". The Guardian. Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Ejerique, Raquel (30 June 2015). "Los siete derechos fundamentales que limita la 'Ley Mordaza'". eldiario.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Calvo, Vera Gutiérrez; Rodríguez Sahuquillo, María (20 December 2013). "El Gobierno aprueba la ley del aborto más restrictiva de la democracia". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "Spain government approves restrictive abortion law despite opposition". The Guardian. Madrid. Associated Press. 20 December 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "La indignación ante la reforma de la ley del aborto, de las redes sociales a la calle". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. 20 December 2013. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "Rajoy confirma la retirada de la ley del aborto por falta de consenso". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. 23 September 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "Spain abortion: Rajoy scraps tighter law". BBC News. 23 September 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Gutiérrez Calvo, Vera; Romero, José Manuel (23 September 2014). "Rajoy deja caer al ministro Gallardón en busca del centro político". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Cruz, Marisa (23 September 2014). "Gallardón se va de la política al ser desautorizado en público por Rajoy". El Mundo (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Urreiztieta, Esteban; Inda, Eduardo (18 January 2013). "Bárcenas pagó sobresueldos en negro durante años a parte de la cúpula del PP". El Mundo (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Inda, Eduardo; Urreiztieta, Esteban (14 July 2013). "Los SMS entre Rajoy y Bárcenas". El Mundo (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "Los escándalos que revelan la dimensión de la corrupción en España" (in Spanish). BBC Mundo. 29 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Juliana, Enric (28 October 2014). "La quiebra moral". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ de Barrón, Íñigo (6 October 2014). "Caja Madrid: a bottomless money pit for Spain's political parties?". El País. Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Pérez, Fernando Jesús (8 October 2014). "Ex-IMF chief targeted in Caja Madrid credit card investigation". El País. Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "'Phantom' credit card scandal haunts Spanish elite". Financial Times. 8 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Pérez, Fernando Jesús (24 October 2014). "El PP pagó otros 750.000 euros en b por obras en su sede central en 2006". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Pérez, Fernando Jesús; Hernández, José Antonio (27 October 2014). "El juez destapa la trama del 3% madrileño". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Marraco, Manuel (27 October 2014). "51 detenidos y un fraude de 250 millones en ayuntamientos y CCAA". El Mundo (in Spanish). Madrid. Agencias. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Pérez, Fernando J.; Romero, José Manuel (26 November 2014). "Ana Mato y el PP se beneficiaron de los fondos delictivos de la red Gürtel". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Elordi Cué, Carlos (26 November 2014). "Dimite Ana Mato para no hundir a Mariano Rajoy". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Manetto, Francesco (2 February 2015). "Podemos inicia su campaña electoral con una marcha en Madrid". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Manresa, Andreu (3 April 2013). "El juez cita como imputada a la infanta Cristina en el 'caso Urdangarin'". El País (in Spanish). Palma de Mallorca. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "Spain's Princess Cristina in court over corruption case". BBC News. 8 February 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "Tax trial confirmed for Spain's Princess Cristina". BBC News. 7 November 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Tremlett, Giles (15 April 2012). "Spain's King Juan Carlos under fire over elephant hunting trip". The Guardian. Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Garea, Fernando (2 June 2014). "La monarquía, en el peor momento de popularidad". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "King Juan Carlos of Spain abdicates". BBC News. 2 June 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "El Congreso de los Diputados amanece blindado por la Policía por la protesta del 25-S". 20 minutos (in Spanish). Agencias. 25 September 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Uzal, Virginia; Giménez, Luis (22 March 2014). "Madrid se llena de 'Dignidad' y anochece con cargas policiales". Público (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "Las Mareas Ciudadanas se manifestan este domingo en Madrid en contra de la troika". Público (in Spanish). Madrid. Agencias. 21 February 2015. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ Garea, Fernando (26 May 2014). "Rubalcaba tira la toalla y convoca en julio un congreso extraordinario tras la debacle". El País (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ B. García, Luis (13 July 2014). "Pedro Sánchez proclama "el principio del fin de Mariano Rajoy como presidente del Gobierno"". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ↑ "Grupos Parlamentarios en el Congreso de los Diputados y el Senado". Historia Electoral.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- 1 2 "Composición del Senado 1977-2024". Historia Electoral.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ↑ "Grupos parlamentarios". Congress of Deputies (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ↑ "Irene Lozano abandona UPyD e irá en las listas del PSOE para las generales" (in Spanish). RTVE. 16 October 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ↑ "Grupos Parlamentarios desde 1977". Senate of Spain (in Spanish). Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- ↑ "Ignacio Cosido, elegido senador por la Comunidad sólo con los votos del PP". Diario de Valladolid (in Spanish). 14 December 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ↑ "Juan Morano pedirá la baja en el PP y pasará al Grupo Mixto en el Senado tras desmarcarse en el conflicto del carbón". Europa Press (in Spanish). 3 July 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "ELECCIONES GENERALES. 20 de diciembre de 2015. Coaliciones válidamente constituidas ante la Junta Electoral Central" (PDF). congreso.es (in Spanish). Congress of Deputies. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ↑ "Alberto Garzón se convierte en el candidato de IU a las generales". infoLibre (in Spanish). 23 January 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ↑ "'Entre tod@s sí se puede Córdoba' y Unidad Popular rompen". Europa Press (in Spanish). 13 November 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ↑ "La reforma fiscal pone fin a la etapa liberal del PNV que abraza con fuerza la socialdemocracia". El Correo (in Spanish). 7 October 2013. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "Carlos Callón, un filólogo para llevar a Madrid un proyecto gallego 'feito na casa'" (in Spanish). RTVE. 24 November 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- 1 2 "Podemos y EH Bildu llegan a un acuerdo en Navarra para ir en una candidatura conjunta al Senado". eldiario.es (in Spanish). 2 November 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- 1 2 "Los candidatos del cuatripartito quieren que en Madrid 'se oiga la voz del cambio en Navarra'". Diario de Navarra (in Spanish). 6 November 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "Rajoy firma en Zaragoza el pacto de coalición con el PAR ante el 20D". El Periódico de Aragón (in Spanish). 5 November 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ↑ "Rajoy anuncia que el PP irá en coalición con el partido de Cascos en Asturias para las elecciones generales". El Mundo (in Spanish). 5 November 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "UPN y PP concurrirán juntos a las próximas elecciones generales". Diario de Navarra (in Spanish). 30 October 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "PP y AMF reeditan la coalición para acudir juntos al Senado por Fuerteventura". eldiario.es (in Spanish). 13 November 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ Santana, Txema (18 October 2015). "El PSOE acudirá a las generales en coalición con Nueva Canarias". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "Extremadura Unida y Extremeños pactan una coalición para ir juntos en las generales". eldiario.es (in Spanish). 12 November 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "Ada Colau impone a Pablo Iglesias su candidato y la marca 'En Comú' por delante del nombre de Podemos". El Mundo (in Spanish). 29 October 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "Pablo Iglesias y Ada Colau buscan sellar una coalición permanente en Catalunya tras el 20-D". El Periódico de Catalunya (in Spanish). 1 December 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "Podemos, Anova y EU registran su coalición En Marea" (in Spanish). Europa Press. 7 November 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "Podemos y Compromís cierran su acuerdo para el 20-D en Valencia". Público (in Spanish). 6 November 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "Compromís impone su nombre en el pacto con Podemos". El Mundo (in Spanish). 7 November 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "Compromís y Podemos se presentarán al 20D en coalición sin EUPV". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 6 November 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "Ahora en Común y Podemos se presentarán a las elecciones generales con una lista única en Huesca". eldiario.es (in Spanish). 17 October 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "Alberto Garzón no quiere ser el enterrador y Pablo Iglesias no quiere ser el enfermero". eldiario.es (in Spanish). 6 October 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "Uralde se perfila como cabeza de lista de Podemos y Equo en Euskadi para las generales". eldiario.es (in Spanish). 6 October 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "CDC y ERC oficializan que irán por separado el 20-D". El Periódico de Catalunya (in Spanish). 30 October 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "CDC concurrirá a las generales bajo el nombre de Democràcia i Llibertat". El Periódico de Catalunya (in Spanish). 6 November 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ Baquero, Camilo S. (19 October 2015). "Duran Lleida repetirá como candidato en plena crisis de Unió". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "Representation of the people Institutional Act". Central Electoral Commission. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- ↑ "Elecciones Generales 20 de diciembre de 2015. Calendario Electoral" (PDF). juntaelectoralcentral.es (in Spanish). Central Electoral Commission. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Á. Carpio, José (3 December 2015). "Pistoletazo a la campaña electoral del 20D, la más abierta y dinámica de los últimos años". RTVE (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Pi, Jaume (3 December 2015). "Los lemas de la campaña". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ruiz Marull, David (11 June 2016). "Lemas sin alma para el 26J". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ↑ Sanz, Gabriel (9 December 2015). ""Un presidente para la mayoría", nuevo lema del PSOE". ABC (in Spanish). Madrid. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "'Possible', el lema de Democràcia i Llibertat". El Periódico de Catalunya (in Spanish). Barcelona. 1 December 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "Unió presenta el lema "¡Soluciones!" para las elecciones generales". Expansión (in Spanish). 30 November 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- 1 2 "PNV, EH Bildu y Podemos abren campaña en Vitoria, y PSE, PP e IU en Bilbao". Europa Press (in Spanish). Bilbao. 2 December 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "Koldo Martínez: "Tenemos el testigo de Uxue y seguiremos corriendo para defender Navarra"". Pamplona Actual (in Spanish). 3 December 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ "Koldo Martínez dice que "cada voto a Geroa Bai va a defender Navarra"". eldiario.es (in Spanish). 18 December 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ "Podemos presenta su lema de campaña: 'Un país contigo'". Expansión (in Spanish). 23 November 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "Colau y Domènech, estrellas del espot coral de campaña de En Comú Podem". El Periódico de Catalunya (in Spanish). 3 December 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "Compromís-Podemos incluye en la cartelería electoral a Oltra y Ribó". Levante-EMV (in Spanish). 3 December 2015. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "¿Qué eslogan ha elegido cada partido de cara al 20-D?". Voz Libre (in Spanish). 3 December 2015. Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ↑ "Iglesias and Rivera will attend a debate before university students to which Rajoy and Sánchez are also invited". Europa Press (in Spanish). 5 November 2015.

- ↑ "Spain to Debate". Asociación Demos (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ↑ Gómez, Rosario G. (6 November 2015). "The first digital debate of democracy, on day 30". El País (in Spanish).

- ↑ "Sánchez, Rivera and Iglesias, protagonists of the first electoral debate on Internet on the next 30 November". Europa Press (in Spanish). 12 November 2015.

- ↑ Gómez, Rosario G.; Casqueiro, Javier (25 November 2015). "EL PAÍS did not accept Santamaría in its debate with party leaders". El País (in Spanish).

- ↑ "The winner of the debate and mentions between candidates". El País (in Spanish). 30 November 2015.

- ↑ "ATRESMEDIA makes history again with the most expected debate by citizens with the four main parties on 7D". laSexta (in Spanish). 24 November 2015. Archived from the original on 2 December 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ↑ "'The Decisive Debate', the most watched broadcast of the year on TV with 9.2 million viewers (48.2%)". Vertele.com (in Spanish). 8 December 2015.

- ↑ "Pablo Iglesias, winner of Atresmedia's 'decisive debate'". El Huffington Post (in Spanish). 8 December 2015. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- ↑ "Soraya 'decisive' and Iglesias moral winner". El Mundo (in Spanish). 8 December 2015.

- ↑ "El Español ratings: Iglesias (7) wins and Sánchez (5.3) ranks fourth". El Español (in Spanish). 8 December 2015.

- ↑ "The PP admits privately that Pablo Iglesias won the debate". Cadena SER (in Spanish). 8 December 2015.

- ↑ "La Sexta gives the edge in the 'bipartisan debate' aired on 13 channels". El Huffington Post (in Spanish). 14 December 2015. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ↑ "Rajoy and Sánchez will debate face-to-face on 14 December". Levante-EMV (in Spanish). 24 November 2015.

- ↑ "El debate Rajoy – Sánchez, lo más visto del año con 9.7 millones y victoria de laSexta" [The Rajoy-Sánchez debate, the most watched broadcast of the year with 9.7 million and victory of laSexta]. Vertele.com (in Spanish). 15 December 2015.

- ↑ "Atresmedia poll: 34.5% vote "none of them" candidates has won". Antena3.com (in Spanish). 15 December 2015. Archived from the original on 17 December 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ↑ "'Salvados' logra récord de audiencia con el debate entre Rivera e Iglesias". El País (in Spanish). 19 October 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ↑ "'Un tiempo nuevo' emite un debate 'a seis' entre los principales partidos". La Opinión de A Coruña (in Spanish). 21 November 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ↑ "Cómo seguir y a qué hora es el 'Debate en 140 Caracteres' de Twitter". Europa Press (in Spanish). 26 November 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ↑ "Iglesias y Rivera, a clase; Rajoy y Sánchez, de novillos". El Español (in Spanish). 27 November 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ↑ "'El Gran Debate' de 'El País', emitido por 13TV, arrasa en las redes sociales". ecoteuve.es (in Spanish). 1 December 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ↑ "Mariano Rajoy y David Bisbal disparan los audímetros este fin de semana". Bluper (in Spanish). 7 December 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ↑ "El debate electoral a cuatro se convierte en la emisión más vista de 2015". Cadena SER (in Spanish). 8 December 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ↑ "El 'debate a nueve' de TVE acierta en audiencias con 2,3 millones de espectadores". Bluper (in Spanish). 10 December 2015. Archived from the original on 24 January 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ↑ "El cara a cara entre Rajoy y Sánchez, lo más visto del año". El País (in Spanish). 15 December 2015. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- ↑ "El ganador del debate y menciones entre candidatos". El País (in Spanish). 30 November 2015.

- ↑ "Santamaría ganó el debate a cuatro y Pedro Sánchez quedó en último lugar, según un sondeo". Europa Press (in Spanish). 11 December 2015.

- 1 2 "Postelectoral Elecciones Generales 2015. Panel (2ª Fase)" (PDF). CIS (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- ↑ "El 34,5% de encuestados cree que ni Mariano Rajoy ni Pedro Sánchez ha ganado el cara a cara". laSexta (in Spanish). 15 December 2015.

- ↑ "Podemos arrives to the election in an euphoria state after a successful "comeback" campaign". Europa Press (in Spanish). 19 December 2015.

- ↑ "Pablo Iglesias excels in his final debate address with a blunt message: "Yes we can"". La Información (in Spanish). 7 December 2015. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016.

- ↑ Mateo, Juan José (8 January 2016). "Citizens recognizes strategic mistakes in the 20-D campaign". El País (in Spanish).

- ↑ "Podemos' "comeback" won it (and the PP)". El Mundo (in Spanish). 20 December 2015.

- ↑ "Podemos and Compromís fill 'la Fonteta'". El Mundo (in Spanish). 18 December 2015.

- ↑ "'La Fonteta' is left small for the central rally of Compromís-Podemos". ABC (in Spanish). 18 December 2015.

- ↑ "Pablo Iglesias sells out all tickets in the place that Pedro Sánchez could not fill in Valencia". ABC (in Spanish). 16 December 2015.

- ↑ "A teen punches Mariano Rajoy in a street of Pontevedra". Cadena SER (in Spanish). 16 December 2015.

- ↑ "Rajoy, assaulted with a punch in his face by a minor during a walk in Pontevedra". La Sexta (in Spanish). 16 December 2015. Archived from the original on 20 December 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ↑ "The youngster that assaulted Rajoy, son of a cousin of Viri, the Prime Minister's wife". 20minutos (in Spanish). 17 December 2015.

- ↑ "Rajoy, wrapped by Merkel and Cameron in Brussels after the assault". La Sexta (in Spanish). 17 December 2015. Archived from the original on 24 December 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ↑ "Rajoy explains Merkel that Podemos can end up in second place". El Periódico de Catalunya (in Spanish). 18 December 2015.

- 1 2 "Elecciones celebradas. Resultados electorales". Ministry of the Interior (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- 1 2 "Elecciones Generales 20 de diciembre de 2015". Historia Electoral.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- ↑ "Elecciones al Senado 2015". Historia Electoral.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ↑ "The PP trusts in reaching 30% despite the attack's management and corruption" (in Spanish). La Información. 13 December 2015. Archived from the original on 14 December 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ↑ "The PSOE lowers its poor target for 20D ahead of the coming disaster" (in Spanish). esdiario. 9 December 2015.

- ↑ "Spain entombs bipartisanship and leaves government in the air". El Mundo (in Spanish). 20 December 2015.

- ↑ "Spain's general election weakens decades of bipartisan hegemony". Financial Times. 21 December 2015.

- ↑ "Spanish election: national newcomers end era of two-party dominance". The Guardian. 21 December 2015.

- ↑ "Citizens' expectations are diluted in the polls" (in Spanish). laSexta. 20 December 2015. Archived from the original on 24 December 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ↑ "Why Citizens did not meet expectations". El Español (in Spanish). 22 December 2015.

- ↑ "Congreso de los Diputados: Votaciones más importantes". Historia Electoral.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 28 September 2017.

External links

Media related to Spanish general election, 2015 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Spanish general election, 2015 at Wikimedia Commons

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)