.jpg.webp) | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Location | Nob Hill, San Francisco, California |

| Coordinates | 37°47′29″N 122°24′27″W / 37.7915°N 122.4074°W |

| Route | Stockton Street |

| Start | Just to the south of Bush Street |

| End | Just to the south of Sacramento Street |

| Operation | |

| Opened | December 29, 1914 |

| Owner | City of San Francisco |

| Operator | City of San Francisco |

| Traffic | Automotive and pedestrian |

| Technical | |

| Length | 911 feet (278 m) |

| No. of lanes | 3 |

| Electrified | 600 V DC parallel overhead lines (Muni Trolleybus) |

| Tunnel clearance | 13 feet (4 m) |

| Width | 50 feet (15 m) |

| Route map | |

The Stockton Street Tunnel is a tunnel in San Francisco, California, which carries its namesake street underneath a section of Nob Hill near Chinatown for about three blocks. It was opened in 1914. The south portal is located just shy of Bush Street, which is about two blocks to the north of Union Square. The north portal is located just to the south of the Sacramento Street intersection.

Design

The tunnel was built to decrease the grade through the hill. Before the tunnel was built, the maximum grade along the route of Stockton Street north from its intersection with Sutter was 18% and the maximum grade south from the intersection with Sacramento was 12%. The tunnel was built with a maximum grade of 4.29% between Sacramento and Sutter.[1] Initial plans in 1909 called for a tunnel 1,400 feet (430 m) long.[2] The planned tunnel was shortened in 1910 to 750 feet (230 m), with a width of 55 feet (17 m) and a height of 25 feet (7.6 m), with stairways to connect the tunnel with Pine and California streets.[3] The bore was narrowed slightly in 1912, with a total planned width of 42 feet (13 m) and a height of 18 feet (5.5 m).[4]

Construction involved lowering Stockton Street near where it passes into the tunnel from the south, evidence for which can still be seen at the building of 417 Stockton Street (Mystic Hotel), where the basement became the ground floor and the former front door is now a visibly marked window bay on the second floor.[5]

History

The tunnel was primarily built for the streetcars of the now defunct F Stockton line.[6] A petition was filed for a new streetcar line by Frank Stringham, representing an unnamed group of investors, with the San Francisco Board of Supervisors on January 23, 1909. Their intent was to create a nearly level route connecting North Beach with the downtown area.[2] George Skaller later took credit for the initial push for a tunnel, saying that the city had studied the idea for at least 20 years, but would never be built as "all city enterprises, on account of the long and windy red tape connected with city enterprises" were doomed by bureaucracy.[7] Stockton was favored over Grant, which was seen as too narrow, or Kearny, which already was franchised to the United Railways.[7]

Although Skaller initially hoped to raise private funding for the tunnel, the Board of Supervisors imposed a requirement allowing the city to take over the railway after ten years at its physical valuation, and no private investors were willing to fund the project. Instead, Skaller turned to the idea of public funding through a special assessment district, labeling the project as an "improvement" for existing roads.[7] The Stockton Street Tunnel Association launched its fundraising campaign in May 1910, hoping to raise $450,000 (equivalent to $10.3 million in 2022[8]) to cover construction costs by creating a special assessment district to fund the improvements. The estimated assessment for a lot 25 by 100 feet (7.6 by 30.5 m) was $62.50 (equivalent to $1,963 in 2022[9]) in 1910.[3] The project adopted the slogan "The open door to North Beach" in May 1910.[10]

The Stockton Street Railway franchise was relinquished to the city in 1910, and suggestions were made that if ferries from Marin would land in North Beach instead of the Ferry Building, the resulting rise in local property values would offset the cost of the assessment.[11] Two assessment districts were set up, in North Beach and Downtown, and projected traffic was estimated to reach 50,000 to 75,000 passengers per hour during the Panama–Pacific International Exposition of 1915. The precedent set by the assessment districts for the Stockton Street Tunnel sparked interest in building a similar tunnel under Fillmore Street and leveling Rincon Hill to increase usable land,[12] but these added works were not carried through.

Final plans for the tunnel were filed by city engineer Marsden Manson in March 1912.[4] By June 1912, the final legal and funding issues were being resolved, and work was to start "within 30 or 60 days."[13] In July 1913, excavation of the bore was planned to take 100 days.[14] During construction, hotel guests were kept awake by work at night[15] and at least one worker was killed by a cave-in.[16] Revenue service through the tunnel was inaugurated by Mayor James Rolph on December 29, 1914.[5]

Streetcar service through the tunnel ended on January 20, 1951,[17] and was re-designated as route 30.[18] Tracks were removed, but electrified overhead wires were retained for trolleybus service.

In 1984, prodded by Chinatown advocates, San Francisco added safety rails for the sidewalk, new lighting, and waterproofing, after a pedestrian was killed by an automobile.[19]

Gallery

Initial design of south portal (1909)

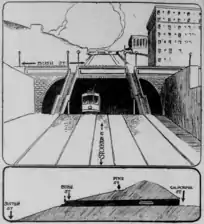

Initial design of south portal (1909) Updated south portal (1910)

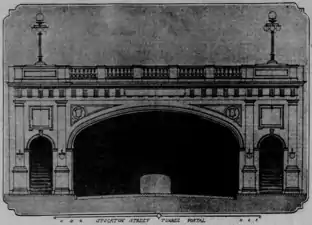

Updated south portal (1910) Final south portal design (1912)

Final south portal design (1912).jpg.webp) North portal from within the tunnel, Chinatown (2016)

North portal from within the tunnel, Chinatown (2016).jpg.webp) Looking out through the south portal (2007)

Looking out through the south portal (2007).jpg.webp) Top of stairs connecting upper Stockton Street with lower Stockton Street (2013)

Top of stairs connecting upper Stockton Street with lower Stockton Street (2013) South portal (2020)

South portal (2020)

In media

SFGATE has remarked on the tunnel's use by filmmakers, noting in particular the "crooked" topography at its southern end at Bush and Stockton streets: "Many dimensions are blurred on the cryptic intersection. [...] The Escher-like dimensions mark the edge of four different neighborhoods. Steep alleys appear from nowhere and plunge onto the sidewalk."[20]

- The opening scene of The Maltese Falcon novel (1929) is set at the corner of Bush and Stockton, atop the southern portal of the tunnel.[20]

- A promotional poster for the 1941 film adaptation of the Maltese Falcon features a man standing in the tunnel, in what SFGATE described as "one of the most evocative noir shots in film history."[20]

- One scene in David Fincher's film The Game (1997) was shot at the same corner.[20]

- In Ron Underwood's film Heart and Souls (1993), a bus crashes above the tunnel and drops to block the Stockton Street Tunnel's entrance.[21]

- In the movie Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings (2021), a fight scene occurs on a bus that travels through the tunnel.[19]

See also

- Central Subway – also tunneled below Stockton Street

- Broadway Tunnel (San Francisco)

References

- ↑ Tilton, E. G. (February 3, 1915). "Method of Constructing Rock Tunnel of 50-Ft. Clear Width, Stockton St., San Francisco". Engineering & Contracting. Vol. 43, no. 5. pp. 93–96. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- 1 2 "Petition for New Franchise Filed". San Francisco Call. January 24, 1909. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- 1 2 "Tunnel Project Rapidly Nears Actual Digging". San Francisco Call. May 13, 1910. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- 1 2 "Classic Style Gives Pleasing Appearance to Subway Entrances". San Francisco Call. March 30, 1912. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- 1 2 King, John (December 21, 2014). "Cityscape: How the Stockton Tunnel made a basement shine". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ "A Brief History of the F-Market & Wharves Line". Market Street Railway. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Skaller, George (August 10, 1912). "Subway Enterprise Is Now Well Started". San Francisco Call. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ↑ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- ↑ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ↑ "'Open Door To North Beach' Is The Slogan That Wins". San Francisco Call. May 14, 1910. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ↑ "Test Case to Fix Tunnel's Legal Status". San Francisco Call. June 12, 1910. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ↑ "Machinery Set In Motion To Build Stockton Street Tunnel". San Francisco Call. December 2, 1911. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ↑ "Construction Work to be Started on Stockton Street Tunnel". San Francisco Call. June 1, 1912. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ↑ "Taking Earth From Stockton Street Bore". San Francisco Call. July 2, 1913. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ↑ "Guests are Kept Awake". San Francisco Call. July 31, 1913. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ↑ "One Killed by Cave-in". Los Angeles Herald. January 3, 1914. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ↑ Perles, Anthony; McKane, John (1982). Inside Muni: The Properties and Operations of the Municipal Railway of San Francisco. Interurban Press. p. 225. ISBN 0-916374-49-1.

- ↑ Elinson, Zusha (March 31, 2012). "After 100 Years, Muni Has Gotten Slower". The New York Times. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- 1 2 Rodriguez, Joe Fitzgerald (September 3, 2021). "In 'Shang-Chi,' a Muni Line Made Possible by Chinatown Community Advocacy". KQED. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Chamings, Andrew (November 17, 2020). "This cryptic corner in downtown San Francisco is a movie treasure". SFGATE. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ↑ "Heart and Souls".

External links

- Wallace, Kevin (December 21, 1952). "The City's Tunnels: When S.F. Can't Go Over, It Goes Under Its Hills". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- Tunneling through San Francisco on a foggy night on YouTube