ᮅᮛᮀ ᮞᮥᮔ᮪ᮓ Urang Sunda | |

|---|---|

A Sundanese couple wearing neo-traditional wedding attire | |

| Total population | |

| c. 40-42 million[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 36,701,670 (2010)[1] | |

| | 34 million |

| | 2,400,000 |

| | 1,500,000 |

| | 600,000 |

| | 300,000 |

| | 100,000 |

| | 90,000 |

| | 80,000 |

| | 60,000 |

| | 50,000 |

| | 40,000 |

| | 30,000 |

| | 20,000 |

| ~1,500 (2015)[2] | |

| Languages | |

| |

| Religion | |

| |

| Related ethnic groups | |

The Sunda or Sundanese (Indonesian: Orang Sunda; Sundanese: ᮅᮛᮀ ᮞᮥᮔ᮪ᮓ, romanized: Urang Sunda) are an indigenous ethnic group native to the western region of Java island in Indonesia, primarily West Java. They number approximately 42 million and form Indonesia's second most populous ethnic group. They speak the Sundanese language, which is part of the Austronesian languages.

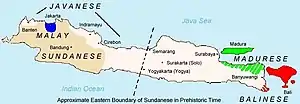

The western third of the island of Java, namely the provinces of West Java, Banten, and Jakarta, as well as the westernmost part of Central Java, is called by the Sundanese people Tatar Sunda or Pasundan (meaning Sundanese land).[3]

Sundanese migrants can also be found in Lampung and South Sumatra, and to a lesser extent in Central Java and East Java. The Sundanese people can also be found on several other islands in Indonesia such as Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Bali and Papua.

Origins

Migration theories

The Sundanese are of Austronesian origins and are thought to have originated in Taiwan. They migrated through the Philippines and reached Java between 1,500 BC and 1,000 BC.[4] Nevertheless, there is also a hypothesis that argues that the Austronesian ancestors of contemporary Sundanese people originally came from Sundaland, a massive sunken peninsula that today forms the Java Sea, the Malacca and Sunda Straits and the islands between them.[5] According to a recent genetic study, Sundanese, together with Javanese and Balinese, has almost an equal ratio of genetic marker shared between Austronesian and Austroasiatic ancestries.[6]

Origin myth

The Sunda Wiwitan belief contains the mythical origin of Sundanese people; Sang Hyang Kersa, the supreme divine being in ancient Sundanese belief created seven bataras (deities) in Sasaka Pusaka Buana (The Sacred Place on Earth). The oldest of these bataras is called Batara Cikal and is considered the ancestor of the Kanekes people. The other six bataras ruled various locations in Sunda lands in Western Java. A Sundanese legend of Sangkuriang contains the memory of the prehistoric ancient lake in Bandung basin highland, which suggest that Sundanese already inhabit the region since the Mesolithic era, at least 20,000 years ago. Another popular Sundanese proverb and legend mentioned the creation of Parahyangan (Priangan) highlands, the heartland of the Sundanese realm; "When the hyangs (gods) were smiling, the land of Parahyangan was created". This legend suggested the Parahyangan highland as the playland or the abode of gods, as well as suggesting its natural beauty.

History

Hindu-Buddhist Kingdoms era

The earliest historical polity that appeared in the Sundanese realm in the Western part of Java was the kingdom of Tarumanagara, which flourished between the 4th and 7th centuries. Hindu influences reached the Sundanese people as early as the 4th century AD, as is evident in Tarumanagara inscriptions. The adoption of this dharmic faith in the Sundanese way of life was, however, never as intense as their Javanese counterparts. It seems that despite the central court beginning to adopt Hindu-Buddhist culture and institution, the majority of common Sundanese still retained their native natural and ancestral worship. By the 4th century, the older megalithic culture was probably still alive and well next to the penetrating Hindu influences. Court cultures flourished in ancient times, for example, during the era of Sunda Kingdom. However, the Sundanese appear not to have had the resources nor desire to construct large religious monuments.[7] The traditional rural Sundanese method of rice farming, by ladang or huma (dry rice farming), also contributed to small populations of sparsely inhabited Sundanese villages.

Geographic constraints that isolate each region also led Sundanese villages to enjoy their simple way of life and their independence even more. That was probably the factor that would contribute to the carefree nature, egalitarian, conservative, independent and somewhat individualistic social outlook of the Sundanese people. The Sundanese seems to love and revere their nature in spiritual ways, leading to them adopting some taboos to conserve nature and maintain the ecosystem. The conservative tendency and their somewhat opposition to foreign influences are demonstrated in extreme isolationist measures adopted keenly by Kanekes or Baduy people. They have rules against interacting with outsiders and adopting foreign ideas, technology, and ways of life. They have also set some taboos, such as not cutting trees or harming forest creatures, to conserve their natural ecosystem.

One of the earliest historical records that mention the name "Sunda" appears in the Sanghyang Tapak inscription dated 952 saka (1030 AD) discovered in Cibadak, near Sukabumi. In 1225, a Chinese writer named Chou Ju-kua, in his book Chu-fan-chi, describes the port of Sin-t'o (Sunda), which probably refers to the port of Banten or Kalapa. By examining these records, it seems that the name "Sunda" started to appear in the early 11th century as a Javanese term used to designate their western neighbours. A Chinese source more specifically refers to it as the port of Banten or Sunda Kelapa. After the formation and consolidation of the Sunda Kingdom's unity and identity during the Pajajaran era under the rule of Sri Baduga Maharaja (popularly known as King Siliwangi), the shared common identity of Sundanese people was more firmly established. They adopted the name "Sunda" to identify their kingdom, their people and their language.

Dutch colonial era

Inland Pasundan is mountainous and hilly, and until the 19th century, it was thickly forested and sparsely populated. The Sundanese traditionally live in small and isolated hamlets, rendering control by indigenous courts difficult. The Sundanese, traditionally engage in dry-field farming. These factors resulted in the Sundanese having a less rigid social hierarchy and more independent social manners.[7] In the 19th century, Dutch colonial exploitation opened much of the interior for coffee, tea, and quinine production, and the highland society took on a frontier aspect, further strengthening the individualistic Sundanese mindset.[7]

Contemporary era

There is a widespread belief among Indonesian ethnicities that the Sundanese are famous for their beauty. In his report "Summa Oriental" on the early 16th century Sunda Kingdom, Portuguese apothecary Tomé Pires mentioned: "The (Sundanese) women are beautiful, and those of the nobles chaste, which is not the case with those of the lower classes". Sundanese women are, as the belief goes, one of the most beautiful in the country due to the climate (they have a lighter complexion than other Indonesians) and a diet featuring raw vegetables (they are said to possess especially soft skin). Bandungite ladies, popularly known as Mojang Priangan are reputedly pretty, fashion smart and forward-looking.[8] Probably because of this, many Sundanese people today pursue careers in the entertainment industry.

Language

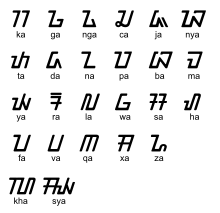

The Sundanese language is spoken by approximately 36 million people in 2010[9] and is the second most widely spoken regional language in Indonesia.[10] The 2000 Indonesia Census put this figure at 30.9 million. This language is spoken in the southern part of the Banten province,[11] and most of West Java and eastwards as far as the Pamali River in Brebes, Central Java.[12]

Sundanese is also closely related to Malay and Minang as it is to Javanese, as seen by the Sundanese utilising different language levels denoting rank and respect – a concept borrowed from the Javanese.[7] It shares similar vocabularies with Javanese and Malay. There are several dialects of Sundanese, from the Sunda–Banten dialect to the Sunda–Cirebonan dialect in the eastern part of West Java until the western part of Central Java Province. Some of the most distinct dialects are from Banten, Bogor, Priangan, and Cirebon. In Central Java, Sundanese is spoken in some of the Cilacap region and some of the Brebes region. It is known that the most refined Sundanese dialect — which is considered as its original form – are those spoken in Ciamis, Tasikmalaya, Garut, Bandung, Sumedang, Sukabumi, and especially Cianjur (The dialect spoken by people living in Cianjur is considered as the most refined Sundanese). The dialect spoken on the north coast, Banten and Cirebon are considered less refined, and the language spoken by Baduy people is considered the archaic type of Sundanese language,[13] before the adoption of the concept of language stratification to denote rank and respect as demonstrated (and influenced) by Javanese.

Today, the Sundanese language is primarily written in Latin script. However, there is an effort to revive the Sundanese script, which was used between the 14th and 18th centuries. For example, street names in Bandung and several cities in West Java are now written in both Latin and Sundanese scripts.

Religion

| Part of a series on |

| Religion of Java |

|---|

|

The initial religious systems of the Sundanese were animism and dynamism with reverence to ancestral (karuhun) and natural spirits identified as hyang, yet bears some traits of pantheism. The best indications are found in the oldest epic poems (wawacan) and among the remote Baduy tribe. This religion is called Sunda Wiwitan ("early Sundanese").[14] The rice agriculture had shaped the culture, beliefs and ritual system of traditional Sundanese people, among other the reverence to Nyai Pohaci Sanghyang Asri as the goddess of rice and fertility. The land of Sundanese people in western Java is among the earliest places in the Indonesian archipelago that were exposed to Indian Hindu-Buddhist influences. Tarumanagara followed by Sunda Kingdom adopted Hinduism as early as the 4th century. The Batujaya stupa complex in Karawang shows Buddhist influences in West Java, while Cangkuang Shivaic temple near Garut shows Hindu influence. The 16th-century sacred text Sanghyang siksakanda ng karesian contains the religious and moral rules, guidance, prescriptions and lessons for ancient Sundanese people. aka Around the 15th to 16th centuries, Islam began to spread among the Sundanese people by Indian Muslim traders, and its adoption accelerated after the fall of the Hindu-animist Sunda Kingdom and the establishment of the Islamic Sultanates of Banten and Cirebon in coastal West Java. Numerous ulama (locally known as "kyai") penetrated villages in the mountainous regions of Parahyangan and established mosques and schools (pesantren) and spread the Islamic faith amongst the Sundanese people. Small traditional Sundanese communities retained their indigenous social and belief systems, adopting self-imposed isolation, and refused foreign influences, proselytism and modernisation altogether, such as those of the Baduy (Kanekes) people of inland Lebak Regency. Some Sundanese villages such as those in Cigugur Kuningan retained their Sunda Wiwitan beliefs, while some villages such as Kampung Naga in Tasikmalaya, and Sindang Barang Pasir Eurih in Bogor, although identifying themselves as Muslim, still uphold pre-Islamic traditions and taboos and venerated the karuhun (ancestral spirits). Today, most Sundanese are Sunni Muslims.

After western Java fell under the control of Dutch East India Company (VOC) in the early 18th century, and later under the Dutch East Indies, Christian evangelism towards the Sundanese people was started by missionaries of Genootschap voor In- en Uitwendige Zending te Batavia (GIUZ). This organisation was founded by Mr F. L. Anthing and Pastor E. W. King in 1851. However, it was Nederlandsche Zendelings Vereeniging (NZV) that sent their missionaries to convert the Sundanese peoples. They started the mission in Batavia, later expanding into several towns in West Java such as Bandung, Cianjur, Cirebon, Bogor and Sukabumi. They built schools, churches and hospitals for native people in West Java. Compared to the large Sundanese Muslim population, the numbers of Christian Sundanese are scarce. Today, Christians in West Java are mostly Chinese Indonesians residing in West Java, with only small numbers of native Sundanese Christians.

In contemporary Sundanese social and religious life, there is a growing shift towards Islamism, especially amongst urban Sundanese.[15][16] Compared to the 1960s, many Sundanese Muslim women today have decided to wear hijab. The same phenomenon was also found earlier in the Malay community in Sumatra and Malaysia. Modern history saw the rise of political Islam through the birth of Darul Islam Indonesia in Tasikmalaya, West Java, back in 1949, although this movement was later cracked down by the Indonesian Republic. In modern contemporary political landscapes, the Sundanese realm in West Java and Banten also provides widespread support for Islamic parties such as the Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) and the United Development Party (PPP). There are numbers of Sundanese ulama and Islamic preachers who have been successful in gaining national popularity, such as Kyai Abdullah Gymnastiar and Mamah Dedeh who have become TV personalities through their dakwah show. There is an increasing number of Sundanese people who consider the Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca) as something that enjoys social prestige. On the other hand, there is also a movement led by the minority Sundanese conservative traditionalist adat, the Sunda Wiwitan community, who are struggling to achieve wider acceptance and recognition of their faith and way of life.

Culture

Family and social relations

Sundanese culture is similar to that of Javanese culture. However, it differs in that it has a much less rigid system of social hierarchy.[7] The Sundanese, in their mentality and behavior, greater egalitarianism and antipathy to yawning class distinctions, and community-based material culture, differ from the feudal hierarchy apparent among the people of Javanese principalities.[17] Central Javanese court culture nurtured an atmosphere conducive to elite, stylised, impeccably polished forms of art and literature. Sundanese culture bore few traces of these traditions.[18]

Culturally, the Sundanese people adopt a bilateral kinship system, with male and female descent of equal importance. In Sundanese families, the important rituals revolved around life cycles, from birth to death, adopting many previous Animist and Hindu-Buddhist, as well as Islamic, traditions. For example, during the seventh month of pregnancy, there is a prenatal ritual called Nujuh Bulanan (identical to Naloni Mitoni in Javanese tradition) which traces its origins to Hindu ritual. Shortly after the birth of a baby, a ritual called Akekahan (from Arabic word: Aqiqah) is performed; an Islamic tradition in which the parents slaughter a goat for a baby girl or two goats for a baby boy, the meat later being cooked and distributed to relatives and neighbors. The circumcision ceremony is performed on prepubescent boys and celebrated with Sisingaan (lion) dance.

The wedding ceremony is the highlight of Sundanese family celebration involving complex rituals from naroskeun and neundeun omong (marriage proposal and agreement conducted by parents and family elders), siraman (bridal shower), seserahan (presenting wedding gifts for the bride), akad nikah (wedding vows), saweran (throwing coins, mixed with flower petals and sometimes also candies, for the unmarried guests to collect and believed to bring better luck in romance), huap lingkung (bride and groom feed each other by the hand, with arms entwined to symbolize love and affection), bakakak hayam (bride and groom ripping a grilled chicken through holding each of its legs; a traditional way to determine which one will dominate the family which is the one that gets the larger or head part), and the wedding feast inviting whole family and business relatives, neighbours, and friends as guests. Death in a Sundanese family is usually performed through a series of rituals in accordance with traditional Islam, such as the pengajian (reciting Al Quran) including providing berkat (rice box with side dishes) for guests. The Quran recitation is performed daily, from the day of death through the seventh day following; later performed again on the 40th day, a year, and the 1,000th day after the passing. This tradition today, however, is not always closely and faithfully followed since growing numbers of Sundanese are adopting a less traditional Islam which does not maintain many of the older traditions.

Artforms

Sundanese literature was basically oral. Their arts (such as architecture, music, dance, textiles, and ceremonies) substantially preserved traditions from an earlier phase of civilization, stretching back even to the Neolithic, and never overwhelmed (as eastward, in Java) by aristocratic Hindu-Buddhist ideas.[18] The art and culture of Sundanese people reflect historical influences by various cultures that include prehistoric native animism and shamanism traditions, ancient Hindu-Buddhist heritage, and Islamic culture. The Sundanese have very vivid, orally-transmitted memories of the grand era of the Sunda Kingdom.[18] The oral tradition of Sundanese people is called Pantun Sunda, a chant of poetic verses employed for story-telling. It is the counterpart of the Javanese tembang, similar to but independent from Malay pantun. The Pantun Sunda often recount Sundanese folklore and legends such as Sangkuriang, Lutung Kasarung, Ciung Wanara, Mundinglaya Dikusumah, the tales of King Siliwangi, and popular children's folk stories such as Si Leungli.

Music

Traditional Sundanese arts include various forms of music, dance, and martial arts. The most notable types of Sundanese music are angklung bamboo music, kecapi suling music, gamelan degung, reyog Sunda and rampak gendang. The Angklung bamboo musical instrument is considered one of the world heritages of intangible culture.[19]

.jpg.webp)

The most well known and distinctive Sundanese dances are Jaipongan,[20] a traditional social dance which is usually, but mistakenly, associated with eroticism. Other popular dances such as the Merak dance describe colourful dancing peafowls. Sisingaan dance is performed mainly in the Subang area to celebrate the circumcision ritual where the boy is seated upon a lion figure carried by four men. Other dances such as the Peafowl dance, Dewi dance and Ratu Graeni dance show Javanese Mataram courtly influences.

Wayang golek puppetry is the most popular wayang performance for Sundanese people. Many forms of kejawen dance, literature, gamelan music and shadow puppetry (wayang kulit) derive from the Javanese.[7] Sundanese puppetry is more influenced by Islamic folklore than the influence of Indian epics present in Javanese versions.[7]

The Pencak silat martial art in Sundanese tradition can be traced to the historical figure King Siliwangi of the Sunda Pajajaran kingdom, with Cimande as one of the most prominent schools. The recently developed Tarung Derajat is also a popular martial art in West Java. Kujang is the traditional weapon of the Sundanese people.

Architecture

The architecture of a Sundanese house is characterised by its functionality, simplicity, modesty, uniformity with little details, its use of natural thatched materials, and its quite faithful adherence to harmony with nature and the environment.[21]

Sundanese traditional houses mostly take basic form of gable roofed structure, commonly called kampung style roof, made of thatched materials (ijuk black aren fibers, kirai, hateup leaves or palm leaves) covering wooden frames and beams, woven bamboo walls, and its structure is built on short stilts. Its roof variations might includes hip and gablet roof (a combination of gable and hip roof).

The more elaborate overhanging gablet roof is called Julang Ngapak, which means "bird spreading wings". Other traditional Sundanese house forms including Buka Pongpok, Capit Gunting, Jubleg Nangkub, Badak Heuay, Tagog Anjing, and Perahu Kemureb.[22]

Next to houses, rice barn or called leuit in Sundanese is also an essential structure in the traditional Sundanese agricultural community. Leuit is essential during Seren Taun harvest ceremony.[23]

Cuisine

Sundanese cuisine is one of the most famous traditional food in Indonesia, and it is also easily found in most Indonesian cities. The Sundanese food is characterised by its freshness; the famous lalab (raw vegetables salad) eaten with sambal (chili paste), and also karedok (peanuts paste) demonstrate the Sundanese fondness for fresh raw vegetables. Similar to other ethnic groups in Indonesia, Sundanese people eat rice for almost every meal. The Sundanese like to say, "If you have not eaten rice, then you have not eaten at all." Rice is prepared in hundreds of different ways. However, it is simple steamed rice that serves as the centrepiece of all meals.

Next to steamed rice, the side dishes of vegetables, fish, or meat are added to provide a variety of tastes as well as for protein, mineral and nutrient intake. These side dishes are grilled, fried, steamed or boiled and spiced with any combination of garlic, galangal (a plant of the ginger family), turmeric, coriander, ginger, and lemongrass. The herb-rich food wrapped and cooked inside banana leaf called pepes (Sundanese: pais) is popular among Sundanese people. Pepes are available in many varieties according to their ingredients; carp fish, anchovies, minced meat with eggs, mushroom, tofu or oncom. Oncom is a fermented peanut-based ingredient that is prevalent within Sundanese cuisine, just like its counterpart, Tempe, which is popular among Javanese people. Usually, the food itself is not too spicy, but it is served with a boiling sauce made by grinding chilli peppers and garlic together. On the coast, saltwater fish are common; in the mountains, fish tend to be either pond-raised carp or goldfish. A well-known Sundanese dish is lalapan, which consists only of raw vegetables, such as papaya leaves, cucumber, eggplant, and bitter melon.[24]

In general, Sundanese food tastes rich and savoury, but not as rich as Padang food, nor as sweet as Javanese food.[25]

In Sundanese culture, there is a culture of eating together known as Cucurak in the Bogor area or Munggahan in the Priangan area. This tradition is usually carried out together with extended family or colleagues when approaching Ramadan.[26]

Occupations

The traditional occupation of Sundanese people is agricultural, especially rice cultivation. Sundanese culture and tradition are usually centred around the agricultural cycle. Festivities such as the Seren Taun harvest ceremony are held in high importance, especially in the traditional Sundanese community in Ciptagelar village, Cisolok, Sukabumi; Sindang Barang, Pasir Eurih village, Taman Sari, Bogor; and the traditional Sundanese community in Cigugur Kuningan.[27] The typical Sundanese leuit (rice barn) is an important part of traditional Sundanese villages; it is held in high esteem as the symbol of wealth and welfare. Since early times, the Sundanese have predominantly been farmers.[18] They tend to be reluctant to be government officers or legislators.[28]

Next to agriculture, Sundanese people often choose business and trade to make a living although most are traditional entrepreneurs, such as travelling food or drink vendors, establishing modest warung (food stalls) or restaurants, as the vendor of daily consumer's goods or open a modest barber shop. Their affinity for establishing and running small-scale entrepreneurship is most likely contributed by the Sundanese tendency to be independent, carefree, egalitarian, individualistic and optimistic. They seem to abhor the rigid structure and rules of government offices. Several traditional travelling food vendors and food stalls such as Siomay, Gado-gado and Karedok, Nasi Goreng, Cendol, Bubur Ayam, Roti Bakar (grilled bread), Bubur kacang hijau (green beans congee) and Indomie instant noodle stall are notably run by Sundanese.

Nevertheless, there are numbers of Sundanese that successfully carved their career as intellectuals or politicians in national politics, government offices and military positions. Some notable Sundanese has gained positions in the Indonesian government as governor, municipal major, vice president and state ministers, also as officers and general in the Indonesian military.

Sundanese is also popularly known as cheerful and mercurial folks, as they love to joke and tease around. The wayang golek artform of Cepot, Dawala, and Gareng punakawan characters demonstrate the Sundanese quirky side. Some Sundanese might find art and culture as their passion and become artists, either in fine art, music or performing art. Today, there are several Sundanese involved in the music and entertainment industry, with some of Indonesia's most famous singers, musicians, composers, cinema directors, film and sinetrons (soap opera) actors being of Sundanese origin.[29]

Notable people

Notable Sundanese that has been recognised as Indonesian national heroes include Dewi Sartika that fought for equality for women's education, and statesmen such as Oto Iskandar di Nata and Djuanda Kartawidjaja. Former governor of Jakarta Ali Sadikin, former vice president Umar Wirahadikusumah, and former defence minister Agum Gumelar, and ministers of foreign affairs such as Mochtar Kusumaatmadja, Hassan Wirajuda and Marty Natalegawa, Meutya Hafid are among notable Sundanese in politics. Ajip Rosidi and Achdiat Karta Mihardja are among Indonesian distinguished poets and writers.

Today, in the modern Indonesian entertainment industry, there are large numbers of Sundanese artists that have become Indonesia's most famous singers, musicians, composers, cinema directors, film and sinetron actors. Famous dangdut singers Rhoma Irama, Elvy Sukaesih and, musicians and composers such as Erwin Gutawa and singers such as Roekiah, Hetty Koes Endang, Vina Panduwinata, Nicky Astria, Nike Ardilla, Poppy Mercury, Rossa, Gita Gutawa and Syahrini, Indonesian sinetrons actors such as Raffi Ahmad, Jihan Fahira and Asmirandah Zantman, also stunt choreographer, movie action star Kang Cecep Arif Rahman, also film director Nia Dinata, are among artists of Sundanese background. Famous wayang golek puppet master was Asep Sunandar Sunarya, while Sule, Jojon and Kang Ibing are a popular comedians. In sports, Indonesian athletes of Sundanese background include badminton Olympic gold medalists Taufik Hidayat and Ricky Subagja.

See also

Notes

- ↑ The total figure is merely an estimation; sum of all the referenced populations below.

References

- ↑ Kewarganegaraan, Suku Bangsa, Agama dan Bahasa Sehari-hari Penduduk Indonesia - Hasil Sensus Penduduk 2010. Badan Pusat Statistik. 2011. ISBN 9789790644175.

- ↑ "Sikap Luwes Rahasia Perantau Sunda di Jepang". ANTARAJABAR. 2015.

- ↑ Sejarah tatar Sunda (in Indonesian). Satya Historika. 2003. ISBN 978-979-96353-7-2.

- ↑ Taylor (2003), p. 7.

- ↑ Oppenheimer, Stephen (1998). Eden in the east: the drowned continent. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-81816-3.

- ↑ "Pemetaan Genetika Manusia Indonesia". Kompas.com (in Indonesian).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hefner (1997)

- ↑ Cale, Roggie; Eric Oey; Gottfried Roelcke (1997). Java, West Java. Periplus. p. 128. ISBN 9789625932446. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ↑ "Sundanesiska". Nationalencyklopedin. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ Taylor (2003), p. 120-121

- ↑ R. Schefold (2014). R. Schefold & Peter J.M. Nas (ed.). Indonesian Houses: Volume 2: Survey of Vernacular Architecture in Western Indonesia, Volume 2. BRILL. p. 577. ISBN 978-900-4253-98-8.

- ↑ Hetty Catur Ellyawati (2015). "Pengaruh Bahasa Jawa Cilacap Dan Bahasa Sunda Brebes Terhadap Pencilan Bahasa (Enklave) Sunda Di Desa Madura Kecamatan Wanareja Kabupaten Cilacap". Universitas Semarang. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- ↑ The Sundanese

- ↑ Dadan Wildan, Perjumpaan Islam dengan Tradisi Sunda, Pikiran Rakyat, 26 March 2003

- ↑ Jajang A. Rohmana (2012). "Sundanese Sufi Literature And Local Islamic Identity: A Contribution of Haji Hasan Mustapa's Dangding" (PDF). State Islamic University (UIN) Sunan Gunung Djati, Bandung, Indonesia. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- ↑ Andrée Feillard & Lies Marcoes (1998). "Female Circumcision in Indonesia : To " Islamize " in Ceremony or Secrecy". Archipel. 56: 337–367. doi:10.3406/arch.1998.3495. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- ↑ James Minahan (2012). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 305–306. ISBN 978-159-8846-59-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Alit Djajasoebrata, Bloemen van net Heelal: De kleurrijke Wereld van de Textiel op Java, A. W. Sijthoffs Uitgeversmaatschappij bv, Amsterdam, 1984

- ↑ KAsep (11 March 2010). "Angklung, Inspirasi Udjo bagi Dunia" (in Indonesian). Kasundaan.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ↑ KAsep (19 November 2009). "Jaipong - Erotismeu Itu Kodrati" (in Indonesian). Kasundaan.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ↑ Mihályi, Gabriella. "ArchitectureWeek - Culture - The Sundanese House - 2007.0307". www.architectureweek.com. Retrieved 2018-05-16.

- ↑ Nurrohman, Muhammad Arif (11 February 2015). "Julang Ngapak, Filosofi Sebuah Bangunan". Budaya Indonesia.

- ↑ "What to discover in West Java cultural village Ciptagelar". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 2018-05-16.

- ↑ KAsep. "Kuliner" (in Indonesian). Kasundaan.org. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ↑ madjalahkoenjit (6 May 2008). "Kuliner Sunda, Budaya yang Tak Lekang Oleh Waktu" (in Indonesian). Koenjit. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- ↑ "Mengenal Tradisi Cucurak, Cara Warga Bogor Sambut Ramadhan". megapolitan.kompas.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ↑ Seren Taun Bogor

- ↑ Ajip Rosidi, Pikiran Rakyat, 2003

- ↑ Rosidi, Ayip. Revitalisasi dan Aplikasi Nilai-nilai Budaya Sunda dalam Pembangunan Daerah.

Further reading

- Hefner, Robert (1997), Java's Five Regional Cultures. taken from Oey, Eric, ed. (1997). Java. Singapore: Periplus Editions. pp. 58–61. ISBN 962-593-244-5.

- Lentz, Linda (2017). The Compass of Life: Sundanese Lifecycle Rituals and the Status of Muslim Women in Indonesia. Carolina Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-61163-846-2.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (January 2003). Indonesia. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10518-5.