Sir Edward Elgar's Symphony No. 1 in A♭ major, Op. 55 is one of his two completed symphonies. The first performance was given by the Hallé Orchestra conducted by Hans Richter in Manchester, England, on 3 December 1908. It was widely known that Elgar had been planning a symphony for more than ten years, and the announcement that he had finally completed it aroused enormous interest. The critical reception was enthusiastic, and the public response unprecedented. The symphony achieved what The Musical Times described as "immediate and phenomenal success", with a hundred performances in Britain, continental Europe and America within just over a year of its première.

The symphony is regularly programmed by British orchestras, and features occasionally in concert programmes in North America and continental Europe. It is well represented on record, with recordings ranging from the composer's 1931 version with the London Symphony Orchestra to modern digital recordings, of which more than 40 have been issued since the mid-1980s.

Composition and première

Nearly ten years before composing his first symphony, Elgar had been intrigued by the idea of writing a symphony to commemorate General Charles George Gordon rather as Beethoven's Eroica was originally intended to celebrate Napoleon Bonaparte.[1] In 1899 he wrote to his friend August Jaeger (the "Nimrod" of the Enigma Variations), "Now as to Gordon: the thing possesses me, but I can't write it down yet."[1] After he completed his oratorio The Kingdom in 1906 Elgar had a brief fallow period. As he passed his 50th birthday he turned to his boyhood compositions which he reshaped into The Wand of Youth suites during the summer of 1907.[2] He began work on a symphony and when he went to Rome for the winter[3] he continued work on it, finishing the first movement. After his return to England he worked on the rest of the symphony during the summer of 1908.[2]

Elgar had abandoned the idea of a "Gordon" symphony, in favour of a wholly non-programmatic work. He had come to consider abstract music as the pinnacle of orchestral composition. In 1905 he gave a lecture on Brahms's Symphony No. 3, in which he said that when music was simply a description of something else it was carrying a large art somewhat further than he cared for. He thought music, as a simple art, was at its best when it was simple, without description, as in the case of the Brahms symphony.[4] The first page of the manuscript carries the title, "Symphony for Full Orchestra, Op. 55."[5] To the music critic Ernest Newman he wrote that the new symphony was nothing to do with Gordon, and to the composer Walford Davies he wrote, "There is no programme beyond a wide experience of human life with a great charity (love) and a massive hope in the future."[2]

The symphony was dedicated "To Hans Richter, Mus. Doc. True Artist and true Friend."[5] It was premiered on 3 December 1908 in the Free Trade Hall in Manchester, with Richter conducting the Hallé Orchestra. Neviille Cardus, as a young man of 20, stood at the back of the hall and "listened with excitement as the broad and long opening melody marched before us ... broad as the broad back of Hans Richter".[6]

The London première followed four days later, at the Queen's Hall, with the London Symphony Orchestra conducted by Richter.[2] At the first rehearsal for the London concert, Richter addressed the orchestra, "Gentlemen, let us now rehearse the greatest symphony of modern times, written by the greatest modern composer – and not only in this country." William Henry Reed, who played in the LSO at that concert, recalled, "Arriving at the Adagio, [Richter] spoke almost with the sound of tears in his voice and said: 'Ah! this is a real Adagio – such an Adagio as Beethove' would 'ave writ'."[5]

The Musical Times said in 1909, "To state that Elgar's Symphony has achieved immediate and phenomenal success is the bare truth". Within weeks of the première the symphony was performed in New York under Walter Damrosch, Vienna under Ferdinand Löwe, St. Petersburg under Alexander Siloti, and Leipzig under Artur Nikisch. There were performances in Chicago, Boston, Toronto and 15 British towns and cities.[7] By February 1909 the New York Philharmonic Orchestra had given two more performances at Carnegie Hall and had taken the work to "some of the largest inland cities ... It is doubtful whether any symphonic work has aroused so great an interest since Tchaikowsky's Pathétique."[8] In the same period the work was played six times in London, under the baton of Richter, the composer, and Henry Wood.[7] Within just over a year there were a hundred performances worldwide.[9]

The Musical Times printed a digest of press comments on the symphony. The Daily Telegraph was quoted as saying, "[T]hematic beauty is abundant. It is exquisite in the adagio, and in the first and second allegros, the latter a kind of scherzo; when the rhythmic impulse, the power and the passion are at their extreme height, when the music becomes almost frenzied in its superb energy, the sense of sheer beauty is still strong." The Morning Post, wrote, "This is a work for the future, and will stand as a legacy for coming generations; in it are the loftiness and nobility that indicate a masterpiece, though its full appreciation will only be from the most serious-minded; to-day we recognise it as a possession of which to be proud." The Evening Standard said, Here we have the true Elgar – strong, tender, simple, with a simplicity bred of inevitable expression. ... The composer has written a work of rare beauty, sensibility, and humanity, a work understandable of all."[10]

The Musical Times refrained from quoting The Observer, which was the only dissenting voice among the main newspapers. It complained that the work was derivative of Mendelssohn, Brahms and Wagner, and thought the theme of the slow movement "cheap ready-made material". It allowed, however, that "Elgar's orchestration is so magnificently modern that the dress disguises the skeleton."[11] This adverse view was in contrast with the praise in The Times: "[A] great work of art, which is lofty in conception and sincere in expression, and which must stand as a landmark in the development of the younger school of English music." In The Manchester Guardian, Samuel Langford described the work as "sublime ... the work is the noblest ever penned for instruments by an English composer."[12]

The Times noted the influence of Wagner and Brahms: "There are characteristic reminiscences of Parsifal... and rhythmically the chief theme looks like an offspring of Brahms" but concluded "it is not only an original work, but one of the most original and most important that has been added to the stock of recent music."[13] The New York Times, which also detected the influence of Parsifal, and, in the finale, of Verdi's Aida, called the symphony "a work of such importance that conductors will not lightly let it drop."[14]

Musical analysis

The work's main key is A-flat major, rare for a symphony. It is scored for three flutes (one doubling piccolo), two oboes and cor anglais, two clarinets and bass clarinet, two bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (including snare drum, bass drum and cymbals), two harps, and strings. It is in four movements:

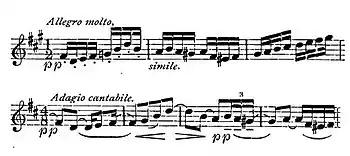

- Andante. Nobilmente e semplice — Allegro

- Allegro molto

- Adagio

- Lento — Allegro

The symphony is in a cyclic form: the incomplete "nobilmente" theme from the first movement returns in the finale for a complete grandioso statement after various transformations throughout the work. Elgar wrote, "the opening theme is intended to be simple &, in intention, noble & elevating ... the sort of ideal call – in the sense of persuasion, not coercion or command – & something above every day & sordid things."[15] The musicologist Michael Kennedy writes "One cannot call it a motto-theme, but it is an idée fixe, and after its first quiet statement, the full orchestra repeat it fortissimo. It gently subsides back to woodwind and violas and abruptly switches to D minor, an extraordinary choice of key for the first allegro of a Symphony in A flat."[16] Reed speculates that Elgar's choice of D minor was a gesture against academic rules.[17] According to the conductor Sir Adrian Boult, the clashing keys arose because someone made a bet with Elgar that he could not compose a symphony in two keys at once.[16] It has also been speculated that the contrast was intended to represent two sides of Elgar's own personality - the successful and popular 'Bard of Empire' is heard in the noble A flat motif, set against the inner worries that continually troubled him.[18] The movement is in traditional sonata form with two main themes, a development and a recapitulation. It ends quietly, "an effect of magical stillness".[19]

The second movement is a brisk allegro. Elgar did not call it a scherzo, and though Reed calls it "vivacious",[20] others, including Kennedy, have found it restless and even sinister in parts.[19] A middle section, in B♭, is in Elgar's Wand of Youth vein. He asked orchestras to play it "like something you hear down by the river."[19] As the movement draws to a close it slows down, and its first theme is transformed into the main theme of the slow movement,[21] despite their contrasting tempi and different keys. According to Reed, "Someone once had the temerity to ask Elgar which version, the allegro or the adagio, was written first; but the question was not very well received and the subject was not pursued."[22]

Kennedy says of the adagio that it is "unique among Elgar slow movements in the absence of that anguished yearning usually to be found in his quieter passages. There is no Angst here, instead a benedictory tranquillity ..."[23] The second subject of the movement remains in the tranquil vein, and the movement ends in what Reed calls "the astounding effect of the muted trombones in the last five bars ... like a voice from another world."[22]

The finale begins in D minor with a slow repeat of one of the subsidiary themes of the first movement, showing Elgar in "one of his most dreamy and mysterious moods."[22] After the introduction there is a restless allegro, with a succession of themes including an "impulsive march-rhythm".[23] In a manner recalling the motivic transformation between the second and third movement, this material is later heard at half speed accompanied by harp arpeggios and with a lyrical string melody. The movement builds to a climax and ends with the nobilmente opening theme of the symphony returning "orchestrated with glittering splendour" to bring the work to a "triumphant and confident" conclusion.[24]

Duration

The composer's 1931 EMI recording of the First Symphony plays for 46 minutes and 30 seconds.[25] The BBC's archives show that in a 1930 broadcast performance Elgar took 46 minutes.[26] Elgar was noted for his brisk tempi in his own music, and later performances have been slower. Elgar's contemporaries, Sir Henry Wood and Sir Hamilton Harty took respectively 50:15 (1930) and 59:45 in 1940.[26] In 1972, while preparing a new recording, Georg Solti studied Elgar's 1931 performance. Solti's fast tempi, based on the composer's own, came as a shock to Elgarians accustomed to the broader tempi taken by Harty, Sir John Barbirolli and others in the mid-20th century.[27] Barbirolli's 1963 recording takes 53:53; Solti takes 48:48. Later examples of slower tempi include a 1992 recording conducted by Giuseppe Sinopoli (55:18), and a 2001 live recording conducted by Sir Colin Davis (54:47).[28]

Recordings

The first recording of the symphony was made by the London Symphony Orchestra in 1931, conducted by the composer for His Master's Voice. The recording was reissued on long-playing record (LP) in 1970,[29] and on compact disc in 1992 as part of EMI's "Elgar Edition" of all the composer's electrical recordings of his works.[30]

After 1931 the work received no further gramophone recordings until Sir Adrian Boult's 1950 recording. During the 1950s there was only one other new recording of the symphony, and in the 1960s there were only two. In the 1970s there were four new recordings. In the 1980s there were six, and the 1990s saw twelve. Ten new recordings were released in the first decade of the 21st century.[31] Most of the recordings have been by British orchestras and conductors, but exceptions include the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra, Dresden Staatskapelle, and Sydney Symphony Orchestra, and conductors Vladimir Ashkenazy, Daniel Barenboim, Bernard Haitink, Tadaaki Otaka, André Previn, Constantin Silvestri, Giuseppe Sinopoli, and Leonard Slatkin.[31][32]

BBC Radio 3's "Building a Library" feature, a comparative review of all available recordings, has considered the symphony three times since 1982. The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music, 2008 edition, contains two pages of reviews of the work. The two recordings recommended by both the BBC and The Penguin Guide are by Boult and the London Philharmonic Orchestra (1977) and Vernon Handley with the same orchestra (1979).[32] [33]

Notes

- 1 2 Reed p. 96

- 1 2 3 4 Kennedy, p. 53

- ↑ "Court Circular", The Times, 6 November 1907, p. 12

- ↑ "Brahms's Third Symphony – Sir E. Elgar's Analysis, The Manchester Guardian, 9 November 1905, p. 8

- 1 2 3 Reed, p. 97

- ↑ Cardus, Neville (1947). Autobiography. London: Collins Fontana. p. 48.

- 1 2 The Musical Times, 1 February 1909, p. 102

- ↑ "Opera in New York – Our Own Correspondent", The Observer, 14 February 1909, p. 5

- ↑ Jack, Adrian. "Edward Elgar, Symphony No 1". BBC Radio 3. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ↑ All extracts in this paragraph are from the digest in The Musical Times, 1 January 1909, pp. 153–54

- ↑ "Music: The Elgar Symphony", The Observer, 13 December 1908, p. 9

- ↑ Langford, Samuel, The Manchester Guardian, 3 December 1908, p. 5; and 4 December 1908, p. 9.

- ↑ "The Queen's-Hall Orchestra", The Times, 2 January 1909, p. 11

- ↑ "Elgar's Symphony – First Time Here". The New York Times, 4 January 1909, p. 9

- ↑ Elgar, Edward. Letter to Ernest Newman, 4 November 1908, reproduced in Edward Elgar: Letters of a Lifetime, ed. Jerrold Northrop Moore (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990), p. 200.

- 1 2 Kennedy, p. 54

- ↑ Reed, p. 158

- ↑ Stephen Johnson, notes to LSO Live recording LSO0017 (2002).

- 1 2 3 Kennedy, p. 55

- ↑ Reed, p. 160

- ↑ Excepting bar 7 of the slow movement where the top A is omitted and the shape is very slightly modified

- 1 2 3 Reed, p. 162

- 1 2 Kennedy, p. 56

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 57 and Reed p. 163

- ↑ EMI CD CDM 5-672-6-2: timings of the movements: I = 17:22, II = 7:37, III = 10:18, and IV = 11:13

- 1 2 Cox, David, "Edward Elgar" in The Symphony 2: Elgar to the Present Day, ed. Robert Simpson (1967), Penguin Books, Harmondsworth. OCLC 500339917.

- ↑ March, p. 431.

- ↑ Notes to EMI CD 9689242; Decca CD 475-8226; DG CD 000289-453-1032-9; and LSO Live CD LSO 0072.

- ↑ Gramophone, December 1970, p. 120

- ↑ Reviews, Gramophone, December 1992, p. 92

- 1 2 Gramophone archive

- 1 2 March, pp. 431–32

- ↑ "Building a Library" BBC CD Review archive, 23 January 1982

References

- Cox, David. "Edward Elgar", in The Symphony, ed. Robert Simpson. Penguin Books Ltd, Middlesex, England, 1967. Vol. 1 ISBN 0-14-020772-4 Vol 2. ISBN 0-14-020773-2

- Kennedy, Michael. Elgar Orchestral Music. BBC Publications, London, 1970

- McVeagh, Diana. "Edward Elgar", in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie. 20 vol. London, Macmillan Publishers Ltd., 1980. ISBN 1-56159-174-2

- McVeagh, Diana."Edward Elgar", Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy. Retrieved 8 May 2005, (subscription access)

- March, Ivan (ed). The Penguin Guide to Recorded Classical Music, Penguin Books, London, 2007. ISBN 978-0-14-103336-5

- Reed, W H. Elgar, J M Dent and Sons Ltd, London, 1943