| T cell deficiency | |

|---|---|

| |

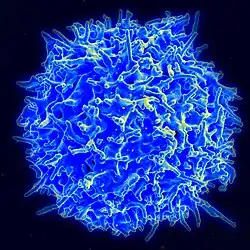

| Human T Cell | |

| Specialty | Immunology |

| Symptoms | Eczematous[1] |

| Types | Primary or Secondary[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Delayed hypersensitivity skin test, T cell count[1][3][4] |

| Treatment | Bone marrow transplant, Immunoglobulin replacement[1][2] |

T cell deficiency is a deficiency of T cells, caused by decreased function of individual T cells, it causes an immunodeficiency of cell-mediated immunity.[1] T cells normal function is to help with the human body's immunity, they are one of the two primary types of lymphocytes(the other being B cells).

Symptoms and signs

Presentations differ among causes, but T cell insufficiency generally manifests as unusually severe common viral infections (respiratory syncytial virus, rotavirus), diarrhea, and eczematous or erythrodermatous rashes.[1] Failure to thrive and cachexia are later signs of a T-cell deficiency.[1]

Mechanism

In terms of the normal mechanism of T cell we find that it is a type of white blood cell that has an important role in immunity, and is made from thymocytes.[5] One sees in the partial disorder of T cells that happen due to cell signaling defects, are usually caused by hypomorphic gene defects.[6] Generally, (micro)deletion of 22Q11.2 is the most often seen.[7]

Pathogens of concern

The main pathogens of concern in T cell deficiencies are intracellular pathogens, including Herpes simplex virus, Mycobacterium and Listeria.[8] Also, intracellular fungal infections are also more common and severe in T cell deficiencies.[8] Other intracellular pathogens of major concern in T cell deficiency are:

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of T cell deficiency can be ascertained in those individuals with this condition via the following:[1][4][3]

- Delayed hypersensitivity skin test

- T cell count

- Detection via culture(infection)

Types

Primary or secondary

- Primary (or hereditary) immunodeficiencies of T cells include some that cause complete insufficiency of T cells, such as severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), Omenn syndrome, and Cartilage–hair hypoplasia.[1]

- Secondary causes are more common than primary ones.[9] Secondary (or acquired) causes are mainly:[9]

Complete or partial deficiency

- Complete insufficiency of T cell function can result from hereditary conditions (also called primary conditions) such as severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), Omenn syndrome, and cartilage–hair hypoplasia.[1]

- Partial insufficiencies of T cell function include acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), and hereditary conditions such as DiGeorge syndrome (DGS), chromosomal breakage syndromes (CBSs), and B-cell and T-cell combined disorders such as ataxia-telangiectasia (AT) and Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome (WAS).[1]

Treatment

In terms of the management of T cell deficiency for those individuals with this condition the following can be applied:[2][1]

- Killed vaccines should be used(not live vaccines in T cell deficiency)

- Bone marrow transplant

- Immunoglobulin replacement

- Antiviral therapy

- Supplemental nutrition

Epidemiology

In the U.S. this defect occurs in about 1 in 70,000, with the majority of cases presenting in early life.[1] Furthermore, SCID has an incidence of approximately 1 in 66,000 in California.[10]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Medscape > T-cell Disorders. Author: Robert A Schwartz, MD, MPH; Chief Editor: Harumi Jyonouchi, MD. Updated: May 16, 2011

- 1 2 3 "Immunodeficiency (Primary and Secondary). Information". patient.info. Retrieved 2017-05-18.

- 1 2 Fried, Ari J.; Bonilla, Francisco A. (2017-05-19). "Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Management of Primary Antibody Deficiencies and Infections". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 22 (3): 396–414. doi:10.1128/CMR.00001-09. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 2708392. PMID 19597006.

- 1 2 "T-cell count: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2017-05-18.

- ↑ Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts k, Walter P (2002) Molecular Biology of the Cell. Garland Science: New York, NY pg 1367

- ↑ Cole, Theresa S.; Cant, Andrew J. (2010). "Clinical experience in T cell deficient patients". Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology. 6 (1): 9. doi:10.1186/1710-1492-6-9. ISSN 1710-1492. PMC 2877019. PMID 20465788.

- ↑ Prasad, Paritosh (2013). Pocket Pediatrics: The Massachusetts General Hospital for Children Handbook of Pediatrics. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. Google books gives no page. ISBN 9781469830094. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- 1 2 Page 435 in: Jones, Jane; Bannister, Barbara A.; Gillespie, Stephen H. (2006). Infection: Microbiology and Management. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-2665-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Page 432, Chapter 22, Table 22.1 in: Jones, Jane; Bannister, Barbara A.; Gillespie, Stephen H. (2006). Infection: Microbiology and Management. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-2665-6.

- ↑ "B-Cell and T-Cell Combined Disorders: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". 2018-12-11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

Further reading

- Verbsky, James W.; Chatila, Talal A. (2017-05-12). "T Regulatory Cells in Primary Immune Deficiencies". Current Opinion in Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 11 (6): 539–544. doi:10.1097/ACI.0b013e32834cb8fa. ISSN 1528-4050. PMC 3718260. PMID 21986549.