Joseph Brant Thayendanegea | |

|---|---|

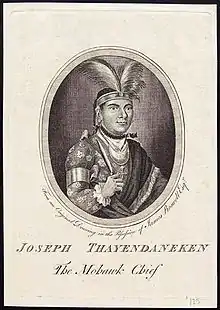

.jpg.webp) A 1776 portrait of Brant by George Romney | |

| Born | Thayendanegea March 1743 Ohio Country along the Cuyahoga River |

| Died | November 24, 1807 (aged 64) |

| Nationality | Mohawk |

| Spouses | |

| Children | John Brant |

| Relatives | Molly Brant (sister) |

| Signature | |

| |

Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant (March 1743 – November 24, 1807) was a Mohawk military and political leader, based in present-day New York and, later, Brantford, in what is today Ontario, who was closely associated with Great Britain during and after the American Revolution. Perhaps the best known Native American of his generation, he met many of the most significant American and British people of the age, including both United States President George Washington and King George III of Great Britain.

While not born into a hereditary leadership role within the Iroquois Confederacy, Brant rose to prominence due to his education, abilities, and connections to British officials. His sister, Molly Brant, was the wife of Sir William Johnson, the influential British Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the Province of New York. During the American Revolutionary War, Brant led Mohawk and colonial Loyalists known as Brant's Volunteers against the rebels in a bitter partisan war on the New York frontier. He was falsely accused by the Americans of committing atrocities and given the name "Monster Brant."

In 1784, Quebec Governor Frederick Haldimand, issued a proclamation that granted Brant and his followers land to replace what they had lost in New York during the Revolution. This tract was about 810,000 hectares (2,000,000 acres) in size, 12 miles (19.2 kilometers) wide along the whole length of the Ouse or Grand River in what is now southwestern Ontario.[2] Brant relocated with many of the Iroquois to the area where the Six Nations Reserve is now located, and remained a prominent leader until his death.

Early years

Brant was born in the Ohio Country in March 1743, somewhere along the Cuyahoga River[3] during the hunting season when the Mohawk traveled to the area from Kanienkeh ("the Land of the Flint"), the Mohawk name for their homeland in what is present-day Upstate New York. He was named Thayendanegea, which in the Mohawk language means "He places two bets together", which came from the custom of tying the wagered items to each other when two parties placed a bet.[4] As the Mohawk were a matrilineal culture, he was born into his mother's Wolf Clan.[4] The Haudenosaunee League, of which the Mohawks were one of the Six Nations, was divided into clans headed by clan mothers.[5] Anglican Church records at Fort Hunter, New York, noted that his parents were Christians and their names were Peter and Margaret Tehonwaghkwangearahkwa.[6] His father died when Joseph was young.[4] One of Brant's friends in later life, John Norton, wrote that Brant's parents were not born Iroquois, but were rather Hurons taken captive by the Iroquois as young people; the Canadian historian James Paxton wrote this claim was "plausible" but "impossible to verify", going on to write that this issue is really meaningless as the Iroquois considered anybody raised as an Iroquois to be Iroquois, drawing no line between those born Iroquois and those adopted by the Iroquois.[5]

After his father's death, his mother Margaret (Owandah) returned to New York from Ohio with Joseph and his sister Mary (also known as Molly). His mother remarried, and her new husband was known by whites as Barnet or Bernard, which was commonly contracted to Brandt or Brant.[4] Molly Brant may have actually been Brant's half-sister rather than his sister, but in Mohawk society, they would have been considered full siblings as they shared the same mother.[5] They settled in Canajoharie, a Mohawk village on the Mohawk River, where they had lived previously. The Mohawk, in common with the other nations of the Haudenosaunee League, had a very gendered understanding of social roles with power divided by the male royaner (chiefs or sachems) and the clan mothers (who always nominated the male leaders). Decisions were reached by consensus between the clan mothers and the chiefs.[7] Mohawk women did all the farming, growing the "Three Sisters" of beans, corn, and squash, while men went hunting and engaged in diplomacy and wars.[7] In the society in which Brant grew up, there was an expectation that he would be a warrior as a man.[7]

The part of the New York frontier where Brant grew up had been settled in the early 18th century by immigrants known as the Palatines, from the Electoral Palatinate in what is now Germany.[8] Relations between the Palatines and Mohawks were friendly, with many Mohawk families renting out land to be farmed by the Palatines (though Mohawk elders complained that their young people were too fond of the beer brewed by the Palatines). Thus Brant grew up in a multicultural world surrounded by people speaking Mohawk, German, and English.[9] Paxton wrote that Brant self-identified as Mohawk, but because he also grew up with the Palatines, Scots, and Irish living in his part of Kanienkeh, he was comfortable with aspects of European culture.[9] The common Mohawk surname Brant was merely the Anglicized version of the common German surname Brandt.[10]

Brant's mother Margaret was a successful businesswoman who collected and sold ginseng, which was greatly valued in Europe for its medical qualities, selling the plant to New York merchants who shipped it to London.[9] Through her involvement in the ginseng trade, Margaret first met William Johnson, a merchant, fur trader, and land speculator from Ireland, who was much respected by the Mohawk for his honesty, being given the name Warraghiagey ("He Who Does Much Business") and who lived in a mansion known as Fort Johnson by the banks of the Mohawk river.[10] Johnson, who was fluent in Mohawk and who lived with two Mohawk women in succession as his common-law wives, had much influence in Kanienkeh.[11] Among the white population, the Butler and Croghan families were close to Johnson while the influential Mohawk families of Hill, Peters and Brant were also his friends.[11] Johnson's Mohawk wife, Caroline, was the niece of the royaner Hendrick Tejonihokarawa, known as "King Hendrick", who visited London to meet Queen Anne in 1710.[12]

In 1752, Margaret began living with Brant Canagaraduncka (alternative spelling: Kanagaraduncka), a Mohawk royaner, and in March 1753 bore him a son named Jacob, which greatly offended the local Church of England minister, the Reverend John Ogilvie, when he discovered that they were not married.[10] On September 9, 1753, his mother married Canagaraduncka at the local Anglican church.[13] Canagaraduncka was also a successful businessman, living in a two-story European style house with all of the luxuries that would be expected in a middle class English household of the period.[10] Her new husband's family had ties with the British; his grandfather Sagayeathquapiethtow was one of the Four Mohawk Kings to visit England in 1710. The marriage bettered Margaret's fortunes, and the family lived in the best house in Canajoharie. Her new alliance conferred little status on her children as Mohawk titles and leadership positions descended through the female line.[14]

Canagaraduncka was a friend of William Johnson, the influential and wealthy British Superintendent for Northern Indian Affairs, who had been knighted for his service. During Johnson's frequent visits to the Mohawk, he always stayed at the Brants' house. Brant's half-sister Molly established a relationship with Johnson, who was a highly successful trader and landowner. His mansion Johnson Hall impressed the young Brant so much that he decided to stay with Molly and Johnson. Johnson took an interest in the youth and supported his English-style education, as well as introducing him to influential leaders in the New York colony. Brant was described as a teenager as an easy-going and affable man who spent his days wandering around the countryside and forests with his circle of friends, hunting and fishing.[15] During his hunting and fishing expeditions, which lasted for days and sometimes weeks, Brant often stopped by at the homes of Palatine and Scots-Irish settlers to ask for food, refreshment and to talk.[16] Brant was well remembered for his charm, with one white woman who let Brant stay with her family for a couple of days in exchange for him sharing some of the deer he killed and to provide a playmate for her boys who were about the same age, recalling after the Revolutionary War that she could never forget his "manly bearing" and "noble goodhearted" ways.[16]

In 1753, relations between the League and the British had become badly strained as land speculators from New York began to seize land belonging to the Iroquois.[17] Led by chief Hendrick Theyanoguin, known to the British as Hendrick Peters, a delegation arrived in Albany to tell the Governor of New York, George Clinton: "The Covenant Chain is broken between you and us. So brother you are not to expect to hear of me any more and Brother we desire to hear no more of you".[18] The end of the "Covenant Chain" as the Anglo-Iroquois alliance had been known since the 17th century was considered a major change in the balance of power in North America.[18] In 1754, the British with the Virginia militia led by George Washington in the French and Indian War in the Ohio river valley were defeated by the French, and in 1755 a British expedition into the Ohio river valley led by General Edward Braddock was annihilated by the French.[18]

Johnson, as Superintendent of Indian Affairs, had the task of persuading the Iroquois Six Nations to fight in the Seven Years' War on the side of the British Crown, despite their own inclinations towards neutrality, and on June 21, 1755, called a conference at Fort Johnson with the Iroquois chiefs and clan mothers to ask them to fight in the war and offered them many gifts.[19] As a 12-year-old, Brant attended the conference, though his role was only as an observer who was there to learn the ways of diplomacy.[19] At the Battle of Lake George, Johnson led a force of British Army troops raised in New York together with Iroquois against the French, where he won a costly victory.[20] As the Iroquois disliked taking heavy losses in war owing to their small population, the Battle of Lake George which had cost the Iroquois many dead set off a deep period of mourning across Kanienkeh and much of the Six Nations leadership swung behind a policy of neutrality again.[20] Johnson was to be sorely tried during the next years as the Crown pressed him to get the Iroquois to fight again while most of the Six Nations made it clear that they wanted no more fighting.[21] Kanagradunckwa was one of the few Mohawk chiefs who favored continuing to fight in the war, which won him much gratitude from Johnson.[21]

Seven Years' War and education

Starting at about age 15 during the French and Indian War (part of the Seven Years' War), Brant took part with Mohawk and other Iroquois allies in a number of British actions against the French in Canada: James Abercrombie's 1758 expedition via Lake George that ended in utter defeat at Fort Carillon; Johnson's 1759 Battle of Fort Niagara; and Jeffery Amherst's 1760 expedition to Montreal via the St. Lawrence River. He was one of 182 Native American warriors awarded a silver medal from the British for his service.

At Fort Carillon (modern Ticonderoga, New York), Brant and the other Mohawk warriors watched the battle from a hill, seeing the British infantry being cut down by the French fire, and returned home without joining the action, being thankful that Abercrombie had assigned the task of storming the fort to the British Army and keeping the Mohawks serving only as scouts.[21] However, the expedition to Fort Carillon introduced Brant to three men who were figure prominently later in his life, namely Guy Johnson, John Butler, and Daniel Claus.[22] At about the same time, Brant's sister, Molly moved into Fort Johnson to become Johnson's common-law wife.[23] The Iroquois did not see anything wrong with the relationship between the twenty-something Molly and the forty-five year old Johnson, and shortly before moving into Fort Johnson, Molly gave birth to a son, Peter Warren Johnson, the first of the eight children she was to have by Sir William.[24]

During the siege of Fort Niagara, Brant served as a scout. Along with a force of British Army soldiers, New York militiamen, and other Iroquois warriors, he took part in an ambush of a French relief force at the Battle of La Belle-Famille, which may have been the first time that Brant saw action.[25] The French force, while marching through the forest towards Fort Niagara, were annihilated during the ambush. On July 25, 1759, Fort Niagara surrendered.[26] In 1760, Brant joined the expeditionary force under General Jeffrey Amherst, which left Fort Oswego on August 11 with the goal of taking Montreal.[26] After taking Fort Lévis on the St. Lawrence, Amherst refused to allow the Indians to enter the fort, fearing that they would massacre the French prisoners in order to take scalps, which caused the majority of the Six Nations warriors to go home, as they wanted to join the British in plundering the fort.[26] Brant stayed on and in September 1760 helped to take Montreal.[26]

In 1761, Johnson arranged for three Mohawk, including Brant, to be educated at Eleazar Wheelock's "Moor's Indian Charity School" in Connecticut. This was the forerunner of Dartmouth College, which was later established in New Hampshire. Brant studied under the guidance of Wheelock, who wrote that the youth was "of a sprightly genius, a manly and gentle deportment, and of a modest, courteous and benevolent temper".[27] Brant learned to speak, read, and write English, as well as studying other academic subjects.[27] Brant was taught how to farm at the school (considered to be woman's work by the Iroquois), math and the classics.[28] Europeans were afterwards astonished when Brant was to speak of the Odyssey to them. He met Samuel Kirkland at the school, later a missionary to Indians in western New York. On May 15, 1763, a letter arrived from Molly Brant at the school ordering her younger brother to return at once, and he left in July.[27] In 1763, Johnson prepared for Brant to attend King's College in New York City.

The outbreak of Pontiac's Rebellion upset his plans, and Brant returned home to avoid hostility toward Native Americans. After Pontiac's rebellion, Johnson did not think it safe for Brant to return to King's College. The ideology behind Pontiac's war was of a pan-Indian theology that at first appeared in the 1730s being taught by various prophets, most notably the Lenape prophet Neolin, which held the Indians and whites were different peoples created by the Master of Life who belonged on different continents and urged the rejection of all aspects of European life.[29] In Kanienkeh, the Mohawks had sufficiently good relations with their Palatine and Scots-Irish neighbours that Neolin's anti-white message never caught on.[29] Pontiac's War caused panic all over the frontier as the news that various Indian tribes had united against the British and were killing all whites, causing terrified white settlers to flee to the nearest British Army forts all over the frontier.[30] Johnson as the superintendent of northern Indian affairs was heavily involved in diplomatic efforts to keep more Indian tribes from joining Pontiac's war, and Brant often served as his emissary.[27] During Pontiac's rebellion, leaders on both sides tended to see the war as a racial war in which no mercy was to be given, and Brant's status as an Indian loyal to the Crown was a difficult one.[31] Even his former teacher Wheelock wrote to Johnson, asking if it was true that Brant "had put himself at the Head of a large party of Indians to fight against the English".[27] Brant did not abandon his interest in the Church of England, studying at a missionary school operated by the Reverend Cornelius Bennet of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, in Canajoharie.[27] However, in Mohawk society, men made their reputations as warriors, not scholars, and Brant abandoned his studies to fight for the Crown against Pontiac's forces.[31]

In February 1764, Brant went on the warpath, joining a force of Mohawk and Oneida warriors to fight for the British.[30] On his way, Brant stayed at the village of Oquaga, whose chief Issac was a Christian, and who became Brant's friend.[30] Brant may have had an ulterior motive when staying with Issac or perhaps romance blossomed, for Issac's daughter was soon to become his wife.[30] In March 1764, Brant participated in one of the Iroquois war parties that attacked Lenape villages in the Susquehanna and Chemung valleys. They destroyed three good-sized towns, burning 130 houses and killing the cattle.[30] No enemy warriors were seen.[32] The Algonquian-speaking Lenape and Iroquois belonged to two different language families; they were traditional competitors and often warred at their frontiers.

Marriages and family

On July 22, 1765, in Canajoharie, Brant married Peggie, also known as Margaret. Said to be the daughter of Virginia planters, Peggie had been taken captive when young by Native Americans. After becoming assimilated with midwestern Indians, she was sent to the Mohawk.[33] They lived with his parents, who passed the house on to Brant after his stepfather's death. He also owned a large and fertile farm of 80 acres (320,000 m2) near the village of Canajoharie on the south shore of the Mohawk River; this village was also known as the Upper Mohawk Castle. Brant and Peggie raised corn and kept cattle, sheep, horses, and hogs. He also kept a small store. Brant dressed in "the English mode" wearing "a suit of blue broad cloth".

Peggie and Brant had two children together, Isaac and Christine, before Peggie died from tuberculosis in March 1771. Brant later killed his son, Isaac, in a physical confrontation.[34][35] Brant married a second wife, Susanna, but she died near the end of 1777 during the American Revolutionary War, when they were staying at Fort Niagara.

While still based at Fort Niagara, Brant started living with Catharine Adonwentishon Croghan, whom he married in the winter of 1780. She was the daughter of Catharine (Tekarihoga), a Mohawk, and George Croghan, the prominent Irish colonist and British Indian agent, deputy to William Johnson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern District. Through her mother, Adonwentishon became clan mother of the Turtle clan, the first in rank in the Mohawk Nation. The Mohawk had a matrilineal kinship system, with inheritance and descent through the maternal line. As the clan matriarch, Adonwentishon had the birth right of naming the Tekarihoga, the principal hereditary sachem of the Mohawk who would come from her clan. Through his marriage to Catherine, Brant also became connected to John Smoke Johnson, a Mohawk godson of Sir William Johnson and relative of Hendrick Theyanoguin.

With Catherine Croghan, Brant had seven children: Joseph, Jacob (1786–1847), John (selected by Catherine as Tekarihoga at the appropriate time; he never married), Margaret, Catherine,[36] Mary, and Elizabeth (who married William Johnson Kerr, grandson of Sir William Johnson and Molly Brant; their son later became a chief among the Mohawk).

Career

With Johnson's encouragement, the Mohawk named Brant as a war chief and their primary spokesman. Brant lived in Oswego, working as a translator with his then-wife Peggy, also known as Neggen or Aoghyatonghsera, where she gave birth to a son who was named Issac after her father.[37] At the end of the year, the Brants moved to back to his hometown of Canajoharie to live with his mother.[38] Brant owned about 80 acres of land in Canajoharie, though it is not clear who worked it.[38] For the Mohawk, farming was woman's work, and Brant would have been mocked by his fellow Mohawk men if he farmed his land himself.[38] It is possible that Brant hired women to work his land, as no surviving record mentions anything about Brant being ridiculed in Canajoharie for farming his land. In 1769, Neggen gave birth to Brant's second child, a daughter named Christina.[38] In early 1771, Neggen died of tuberculosis, leaving the widower Brant with two children to raise.[38]

In the spring of 1772, Brant moved to Fort Hunter to stay with the Reverend John Stuart. He became Stuart's interpreter and teacher of Mohawk, collaborating with him to translate the Anglican catechism and the Gospel of Mark into the Mohawk language.[38] His interest in translating Christian texts had begun during his early education. At Moor's Charity School for Indians, he did many translations. Brant became Anglican, a faith he held for the remainder of his life. Brant, who by all accounts was heartbroken by the death of his wife, found much spiritual comfort in the teachings of the Church of England.[38] However, he was disappointed when the Reverend Stuart refused his request to marry him to Susanna, the sister of Neggen.[38] For the Haudenosaunee, it was the normal custom for a widower to marry his sister-in-law to replace his lost wife, and Brant's marriage to Susanna was considered to be quite acceptable to them.[38]

Aside from being fluent in English, Brant spoke at least three, and possibly all, of the Six Nations' Iroquoian languages. From 1766 on, he worked as an interpreter for the British Indian Department. During this time, Brant became involved in a land dispute with Palatine fur trader George Klock who specialized in getting Mohawks drunk before having them sign over their land to him.[39] Brant demanded that Klock stop obtaining land via this method and return the land he already owned. The dispute led Klock to sail to London in an attempt to have King George III support him, but he refused to see the "notorious bad character" Klock.[38] Upon his return to the New York province, Brant stormed into Klock's house in an attempt to intimidate him into returning the land he had signed over to him; the meeting ended with Mohawk warriors sacking Klock's house while Klock later claimed that Brant had pistol-whipped him and left him bleeding and unconscious.[38] At a meeting at Johnston Hall with the Haudenosaunee leaders, Johnson attempted to mediate the dispute with Klock and died later the same night.[38] Though disappointed that Johnson was not more forceful in supporting the Haudenosaunee against Klock, Brant attended the Church of England services for Johnson, and then together with his sister Molly, Brant performed a traditional Iroquois Condolence ceremony for Johnson.[40] Johnson Hall was inherited by his son John Johnson, who evicted his stepmother, Molly Brant, who returned to Canajoharie with the 8 children she had borne Sir William to live with her mother.[40] Sir John Johnson wished only to attend to his estate and did not share his father's interests in the Mohawk.[40] Daniel Claus, the right-hand man of Sir William, had gone to live in Montreal, and Guy Johnson, the kinsman of Sir William, lacked the charm and tact necessary to maintain social alliances.[40]

Johnson's death left a leadership vacuum in Tryon County which led to a group of colonists to form, on August 27, 1774, a Committee of Public Safety that was ostensibly concerned with enforcing the boycott of British goods ordered by the Continental Congress, but whose real purpose was to challenge the power of the Johnson family in Tryon County.[41] In the summer and fall of 1774, Brant's main concern was his ongoing dispute with Klock, but given his family's close links with the Johnson family, he found himself opposing the Committee of Public Safety.[42]

American Revolution

In 1775, he was appointed departmental secretary with the rank of Captain for the new British Superintendent's Mohawk warriors from Canajoharie. In April 1775, the American Revolution began with fighting breaking out in Massachusetts, and in May 1775, Brant traveled to a meeting at German Flatts to discuss the crisis.[43] While traveling to German Flatts, Brant felt first-hand the "fear and hostility" held by the whites of Tryon County who hated him both for his tactics against Klock and as a friend of the powerful Johnson family.[43] Guy Johnson suggested that Brant go with him to Canada, saying that both their lives were in danger.[44] When Loyalists were threatened after the war broke out in April 1775, Brant moved to the Province of Quebec, arriving in Montreal on July 17.[45] The governor of Quebec, General Guy Carleton, personally disliked Johnson, felt his plans for employing the Iroquois against the rebels to be inhumane, and treated Brant with barely veiled contempt.[45] Brant's wife Susanna and children went to Onoquaga in south central New York, a Tuscarora Iroquois village along the Susquehanna River, the site of present-day Windsor.

On November 11, 1775, Guy Johnson took Brant with him to London to solicit more support from the government. They hoped to persuade the Crown to address past Mohawk land grievances in exchange for their participation as allies in the impending war.[45] Brant met George III during his trip to London, but his most important talks were with the colonial secretary, George Germain.[45] Brant complained that the Iroquois had fought for the British in the Seven Years' War, taking heavy losses, yet the British were allowing white settlers like Klock to defraud them of their land.[45] The British government promised the Iroquois people land in Quebec if the Iroquois nations would fight on the British side in what was shaping up as open rebellion by the American colonists. In London, Brant was treated as a celebrity and was interviewed for publication by James Boswell.[46] He was received by King George III at St. James's Palace. While in public, he dressed in traditional Mohawk attire. He was accepted into freemasonry and received his ritual apron personally from King George.[45]

Brant returned to Staten Island, New York, in July 1776. He participated with Howe's forces as they prepared to retake New York. Although the details of his service that summer and fall were not officially recorded, Brant was said to have distinguished himself for bravery. He was thought to be with Clinton, Cornwallis, and Percy in the flanking movement at Jamaica Pass in the Battle of Long Island in August 1776.[47] He became lifelong friends with Lord Percy, later Duke of Northumberland, in what was his only lasting friendship with a white man.

On his return voyage to New York City, Brant's ship was attacked by an American privateer, during which he used one of the rifles he received in London to practice his sniping skills.[48] In November, Brant left New York City and traveled northwest through Patriot-held territory.[45] Disguised, traveling at night and sleeping during the day, he reached Onoquaga, where he rejoined his family. Brant asked the men of Onquaga to fight for the Crown, but the warriors favored neutrality, saying they wished to have no part in a war between white men.[48] In reply, Brant stated that he had received promises in London that if the Crown won, Iroquois land rights would be respected while he predicted if the Americans won, then the Iroquois would lose their land, leading him to the conclusion that neutrality was not an option.[48] Brant noted that George Washington had been a prominent investor in the Ohio Company, whose efforts to bring white settlement to the Ohio river valley had been the cause of such trouble to the Indians there, which he used to argue did not augur well if the Americans should win. More importantly, one of the "oppressive" acts of Parliament that had so incensed the Americans was the Royal Proclamation of 1763, forbidding white settlement beyond the Appalachians, which did not bode well for Indian land rights should the Americans be victorious.[49]

Brant's own relations with the British were strained. John Butler who was running the Indian Department in the absence of Guy Johnson had difficult relations with Brant.[48] Brant found Butler patronizing while Brant's friend Daniel Claus assured him that Butler's behavior was driven by "jealousy and envy" at the charismatic Brant.[48] At the end of December, Brant was at Fort Niagara. He traveled from village to village in the confederacy throughout the winter, urging the Iroquois to enter the war as British allies.[48] Many Iroquois balked at Brant's plans. In particular, the Oneida and Tuscarora gave Brant an unfriendly welcome.[48] Joseph Louis Cook, a Mohawk leader who supported the rebel American colonists, became a lifelong enemy of Brant's.

The full Grand Council of the Six Nations had previously decided on a policy of neutrality at Albany in 1775. They considered Brant a minor war chief and the Mohawk a relatively weak people. Frustrated, Brant returned to Onoquaga in the spring to recruit independent warriors. Few Onoquaga villagers joined him, but in May he was successful in recruiting Loyalists who wished to retaliate against the rebels. This group became known as Brant's Volunteers. Brant's Volunteers consisted of a few Mohawk and Tuscarora warriors and 80 white Loyalists.[48] Paxton commented it was a mark of Brant's charisma and renown that white Loyalists preferred to fight under the command of a Mohawk chief who was unable to pay or arm them while at the same time that only a few Iroquois joined him reflected the generally neutralist leanings of most of the Six Nations.[48] The majority of the men in Brant's Volunteers were white.[48]

In June, he led them to Unadilla to obtain supplies. There he was confronted by 380 men of the Tryon County militia led by Nicholas Herkimer. The talks with Herkimer, a Palatine who had once been Brant's neighbour and friend, were initially friendly.[50] However, Herkimer's chief of staff was Colonel Ebenezer Cox, the son-in-law of Brant's archenemy Klock, and he continually made racist remarks to Brant, which at one point caused Brant's Mohawk warriors to reach for their weapons.[50] Brant and Herkimer were able to defuse the situation with Brant asking his warriors to step outside while Herkimer likewise told Cox to leave the room.[50] Herkimer requested that the Iroquois remain neutral but Brant responded that the Indians owed their loyalty to the King.

Northern campaign

Service as war leader, 1777–78 and "Monster Brant"

In July 1777 the Six Nations council decided to abandon neutrality and enter the war on the British side. Four of the six nations chose this route, and some members of the Oneida and Tuscarora, who otherwise allied with the rebels. Brant was not present, but was deeply saddened when he learned that Six Nations had broken into two with the Oneida and Tuscarora supporting the Americans while the Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca chose the British.[48] Sayenqueraghta and Cornplanter were named as the war chiefs of the confederacy. The Mohawk had earlier made Brant one of their war chiefs; they also selected John Deseronto.

In July, Brant led his Volunteers north to link up with Barry St. Leger at Fort Oswego. St. Leger's plan was to travel downriver, east in the Mohawk River valley, to Albany, where he would meet the army of John Burgoyne, who was coming from Lake Champlain and the upper Hudson River. St. Leger's expedition ground to a halt with the Siege of Fort Stanwix. General Herkimer raised the Tryon County militia, which consisted mostly of Palatines, to march for the relief of Fort Stanwix while Molly Brant passed along a message to her brother that Herkimer was coming.[51] Brant played a major role in the Battle of Oriskany, where an American relief expedition was stopped on August 6.[51] As Herkimer marched through the forest at the head of a force of 800, they were ambushed by the Loyalists, who brought down heavy fire from their positions in the forest.[51] The Americans stood their ground, and after six hours of fighting, the battle ended inconclusively, though the Americans losses, at about 250 dead, were much greater than the Loyalist losses.[51] The Canadian historian Desmond Morton described Brant's Iroquois warriors as having "annihilated a small American army".[52]

Though Brant stopped Herkimer, the heavy losses taken by the Loyalist Iroquois at Oriskany led the battle to be considered a disaster by the Six Nations, for whom the loss of any life was unacceptable, making the 60 Iroquois dead at Oriskany a catastrophe by Iroquois standards.[51] St. Leger was eventually forced to lift the siege when another American force approached, and Brant traveled to Burgoyne's main army to inform him.[53] The Oneida, who had sided with the Americans together with the Tryon County militia sacked Canajoharie, taking particular care to destroy Molly Brant's house.[51] Burgoyne restricted participation by native warriors, so Brant departed for Fort Niagara, where his family joined him and he spent the winter planning the next year's campaign. His wife Susanna likely died at Fort Niagara that winter. (Burgoyne's campaign ended with his surrender to the Patriots after the Battles of Saratoga.) Helping Brant's career was the influence of his sister Molly, whom Daniel Claus had stated: "one word from her [Molly Brant] is more taken notice of by the Five Nations than a thousand from a white man without exception".[54] The British Army officers found Molly Brant to be bad-tempered and demanding, as she expected to be well rewarded for her loyalty to the Crown, but as she possessed much influence, it was felt to be worth keeping her happy.[54]

In April 1778, Brant returned to Onoquaga. He became one of the most active partisan leaders in the frontier war. He and his Volunteers raided rebel settlements throughout the Mohawk Valley, stealing their cattle, burning their houses, and killing many. The British historian Michael Johnson called Brant the "scourge of the American settlements of New York and Pennsylvania", being one of the most feared Loyalist irregular commanders in the war.[55] Morton wrote the fighting on the New York frontier was not so much between Americans and the British as "a cruel civil war between Loyalist and Patriot, Mohawk and Oneida, in a crude frontier tradition".[56] On May 30, Brant led an attack on Cobleskill. At the Battle of the Cobleskill, Brant ambushed an American force of 50 men, consisting of Continental Army regulars and New York militiamen, killing 20 Americans and burning down the farms.[54] In September, along with Captain William Caldwell, he led a mixed force of Indians and Loyalists in a raid on German Flatts. During the raid on German Flatts, Brant burned down almost the entire village, sparing only the church, the fort, and two houses belonging to Loyalists.[57] Brant's fame as a guerrilla leader was such that the Americans credited him with being behind any attack by Loyalist Haudenosaunee, even when he was not.[58] In the Battle of Wyoming in July, the Seneca were accused of slaughtering noncombatant civilians. Although Brant was suspected of being involved, he did not participate in that battle, which nonetheless gave him the unflattering epithet of "Monster Brant".[57]

In September 1778 Brant's forces attacked Percifer Carr farm where rebel/patriotic scouts under Adam Helmer were located. Three of the scouts were killed; Helmer took off running to the north-east, through the hills, toward Schuyler Lake and then north to Andrustown (near present-day Jordanville, New York) where he warned his sister's family of the impending raid and obtained fresh footwear. He also warned settlers at Columbia and Petrie's Corners, most of whom then fled to safety at Fort Dayton. When Helmer arrived at the fort, severely torn up from his run, he told Colonel Peter Bellinger, the commander of the fort, that he had counted at least 200 of the attackers en route to the valley (see Attack on German Flatts). The straight-line distance from Carr's farm to Fort Dayton is about thirty miles, and Helmer's winding and hilly route was far from straight. It was said that Helmer then slept for 36 hours straight. During his sleep, on September 17, 1778, the farms of the area were destroyed by Brant's raid. The total loss of property in the raid was reported as: 63 houses, 59 barns, full of grain, 3 grist mills, 235 horses, 229 horned cattle, 279 sheep, and 93 oxen. Only two men were reported killed in the attack, one by refusing to leave his home when warned.

In October 1778, Continental soldiers and local militia attacked Brant's home base at Onaquaga while his Volunteers were away on a raid. The soldiers burned the houses, killed the cattle, chopped down the apple trees, spoiled the growing corn crop, and killed some native children found in the corn fields. The American commander later described Onaquaga as "the finest Indian town I ever saw; on both sides [of] the river there was about 40 good houses, square logs, shingles & stone chimneys, good floors, glass windows." In November 1778, Brant joined his Mohawk forces with those led by Walter Butler in the Cherry Valley massacre.[59] Brant disliked Butler, who he found to be arrogant and patronizing, and several times threatened to quit the expedition rather than work with Butler.[57] As Brant's force was mostly Seneca and he was a Mohawk, his own relations with the men under his command were difficult.[57]

Butler's forces were composed primarily of Seneca angered by the rebel raids on Onaquaga, Unadilla, and Tioga, and by accusations of atrocities during the Battle of Wyoming. The force rampaged through Cherry Valley, a community in which Brant knew several people. He tried to restrain the attack, but more than 30 noncombatants were reported slain in the attack.[57] Several of the dead at Cherry Valley were Loyalists like Robert Wells who was butchered in his house with his entire family.[57] Paxton argued that it is very unlikely that Brant would have ordered Wells killed, who was a long-standing friend of his.[57] Patriot Americans believed that Brant had commanded the Wyoming Valley massacre of 1778, and also considered him responsible for the Cherry Valley massacre. At the time, frontier rebels called him "the Monster Brant", and stories of his massacres and atrocities were widely propagated. The violence of the frontier warfare added to the rebel Americans' hatred of the Iroquois and soured relations for 50 years. While the colonists called the Indian killings "massacres", they considered their own forces' widespread destruction of Indian villages and populations simply as part of the partisan war, but the Iroquois equally grieved for their losses. Long after the war, hostility to Brant remained high in the Mohawk Valley; in 1797, the governor of New York provided an armed bodyguard for Brant's travels through the state because of threats against him.

Some historians have argued that Brant had been a force for restraint during the campaign in the Mohawk Valley. They have discovered occasions when he displayed compassion, especially towards women, children, and non-combatants. One British officer, Colonel Mason Bolton, the commander of Fort Niagara, described in a report to Sir Frederick Haldimand, described Brant as treating all prisoners he had taken "with great humanity".[57] Colonel Ichabod Alden said that he "should much rather fall into the hands of Brant than either of them [Loyalists and Tories]."[60] But, Allan W. Eckert asserts that Brant pursued and killed Alden as the colonel fled to the Continental stockade during the Cherry Valley attack.[61] Morton wrote: "An American historian, Barbara Graymount, has carefully demolished most of the legend of savage atrocities attributed to the Rangers and the Iroquois and confirmed Joseph Brant's own reputation as a generally humane and forbearing commander".[56] Morton wrote that the picture of Brant as a mercenary fighting only for "rum and blankets" given to him by the British was meant to hide the fact "that the Iroquois were fighting for their land" as most American colonists at the time "rarely admitted that the Indians had a real claim to the land".[56] As the war went on and became increasingly unpopular in Britain, opponents of the war in Great Britain used the "Monster Brant" story as a way of attacking the Prime Minister, Lord North, arguing the Crown's use of the "savage" Mohawk war chief was evidence of the immorality of Lord North's policies.[56] As Brant was a Mohawk, not British, it was easier for anti-war politicians in Britain to make him a symbol of everything that was wrong with the government of Lord North, which explains why paradoxically the "Monster Brant" story was popular on both sides of the Atlantic.[56]

Lt. Col. William Stacy of the Continental Army was the highest-ranking officer captured by Brant and his allies during the Cherry Valley massacre. Several contemporary accounts tell of the Iroquois stripping Stacy and tying him to a stake, in preparation for what was ritual torture and execution of enemy warriors by Iroquois custom. Brant intervened and spared him. Some accounts say that Stacy was a Freemason and appealed to Brant on that basis, gaining his intervention for a fellow Mason.[62][63][64][65] Eckert, a historian and historical novelist, speculates that the Stacy incident is "more romance than fact", though he provides no documentary evidence.[66]

During the winter of 1778–1779, Brant's wife Susanna, died, leaving him with the responsibility of raising their two children, Issac and Christina alone.[57] Brant chose to have children stay in Kanienkeh, deciding that a frontier fort was no place for children.[57] For Brant, being away from his children as he went to campaign in the war was a source of much emotional hardship.[57]

Commissioned as officer, 1779

In February 1779, Brant traveled to Montreal to meet with Frederick Haldimand, the military commander and Governor of Quebec. Haldimand commissioned Brant as Captain of the Northern Confederated Indians. He also promised provisions, but no pay, for his Volunteers. Assuming victory, Haldimand pledged that after the war ended, the British government would restore the Mohawk to their lands as stated before the conflict started. Those conditions were included in the Proclamation of 1763, the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768, and the Quebec Act in June 1774. Haldimand gave Brant the rank of captain in the British Army as he found Brant to the most "civilized" of the Iroquois chiefs, finding him not to be a "savage".[57]

In May, Brant returned to Fort Niagara where, with his new salary and plunder from his raids, he acquired a farm on the Niagara River, six miles (10 km) from the fort. To work the farm and to serve the household, he used slaves captured during his raids. Brant also bought a slave, a seven-year-old African-American girl named Sophia Burthen Pooley. She served him and his family for six years before he sold her to an Englishman named Samuel Hatt for $100.[67][68] He built a small chapel for the Indians who started living nearby. There he also married for a third time, to Catherine Croghan (as noted above in Marriage section).

Brant's honors and gifts caused jealousy among rival chiefs, in particular the Seneca war chief Sayenqueraghta. A British general said that Brant "would be much happier and would have more weight with the Indians, which he in some measure forfeits by their knowing that he receives pay". In late 1779, after receiving a colonel's commission for Brant from Lord Germain, Haldimand decided to hold it without informing Brant.[69]

Over the course of a year, Brant and his Loyalist forces had reduced much of New York and Pennsylvania to ruins, causing thousands of farmers to flee what had been one of the most productive agricultural regions on the eastern seaboard.[70] As Brant's activities were depriving the Continental Army of food, General George Washington ordered General John Sullivan in June 1779 to invade Kanienkeh and destroy all of the Haudenosaunee villages.[70] In early July 1779, the British learned of plans for a major American expedition into Iroquois Seneca country. To disrupt the Americans' plans, John Butler sent Brant and his Volunteers on a quest for provisions and to gather intelligence in the upper Delaware River valley near Minisink, New York. After stopping at Onaquaga, Brant attacked and defeated American militia at the Battle of Minisink on July 22, 1779. Brant's raid failed to disrupt the Continental Army's plans, however.

In the Sullivan Expedition, the Continental Army sent a large force deep into Iroquois territory to attack the warriors and, as importantly, destroy their villages, crops and food stores. Brant's Volunteers harassed, but were unable to stop Sullivan who destroyed everything in his path, burning down 40 villages and 160,000 bushels of corn.[70] The Haudenosauee still call Washington "Town Destroyer" for the Sullivan expedition.[70] As Brant looked over the devastated land of Kanienkeh he wrote in a letter to Claus: "We shall begin to know what is to befal [befall] us the People of the Long House".[70] Brant and the Iroquois were defeated on August 29, 1779, at the Battle of Newtown, the only major conflict of the expedition. Sullivan's Continentals swept away all Iroquois resistance in New York, burned their villages, and forced the Iroquois to fall back to Fort Niagara. Brant wintered at Fort Niagara in 1779–80. To escape the Sullivan expedition, about 5,000 Senecas, Cayugas, Mohawks and Onondagas fled to Fort Niagara, where they lived in squalor, lacking shelter, food and clothing, which caused many to die over the course of the winter.[70]

Brant pressed the British Army to provide more for his own people while at the same time finding time to marry for a third time.[70] Brant's third wife, Adonwentishon, was a Mohawk clan mother, a position of immense power in Haudenosauee society, and she did much to rally support for her husband.[71] Haldimand had decided to withhold Brant the rank of colonel in the British Army that he had been promoted to, believing that such a promotion would offend other Loyalist Haudenosauee chiefs, especially Sayengaraghta, who viewed Brant as an upstart and not their best warrior, but he did give him the rank of captain.[69] Captain Brant tried his best to feed about 450 Mohawk civilians who had been placed in his care by Johnson, which caused tensions with other British Army officers who complained that Brant was "more difficult to please than any of the other chiefs" as he refused to take no for an answer when he demanded food, shelter and clothing for the refugees.[69] At one point, Brant was involved in a brawl with an Indian Department employee whom he had accused of not doing enough to feed the starving Mohawks.[70]

Wounded and service in Detroit area, 1780–1783

In early 1780, Brant resumed small-scale attacks on American troops and white settlers in the Mohawk and Susquehanna river valleys.[69] In February 1780, he and his party set out, and in April attacked Harpersfield.[69] In mid-July 1780 Brant attacked the Oneida village of Kanonwalohale, as many of the nation fought as allies of the American colonists.[69] Brant's raiders destroyed the Oneida houses, horses, and crops. Some of the Oneida surrendered, but most took refuge at Fort Stanwix.

Traveling east, Brant's forces attacked towns on both sides of the Mohawk River: Canajoharie on the south and Fort Plank. He burned his former hometown of Canajoharie because it had been re-occupied by American settlers. On the raiders' return up the valley, they divided into smaller parties, attacking Schoharie, Cherry Valley, and German Flatts. Joining with Butler's Rangers and the King's Royal Regiment of New York, Brant's forces were part of a third major raid on the Mohawk Valley, where they destroyed settlers' homes and crops. In August 1780, during a raid with the King's Royal Regiment of New York in the Mohawk valley, about 150,000 bushels of wheat were burned.[69] Brant was wounded in the heel at the Battle of Klock's Field.

In April 1781, Brant was sent west to Fort Detroit to help defend against Virginian George Rogers Clark's expedition into the Ohio Country. In August 1781, Brant soundly defeated a detachment of Clark's force, capturing about 100 Americans and ending the American threat to Detroit.[69] Brant's leadership was praised by British Army officers who described him as an intelligent, charismatic and very brave commander.[69] He was wounded in the leg and spent the winter 1781–82 at the fort. During 1781 and 1782, Brant tried to keep the disaffected western Iroquois nations loyal to the Crown before and after the British surrendered at Yorktown in October 1781.

In June 1782, Brant and his Indians went to Fort Oswego, where they helped rebuild the fort.[69] In July 1782, he and 460 Iroquois raided forts Herkimer and Dayton, but they did not cause much serious damage. By 1782, there was not much left to destroy in New York and during the raid Brant's forces killed 9 men and captured some cattle.[69] Sometime during the raid, he received a letter from Governor Haldimand, announcing peace negotiations, recalling the war party and ordering a cessation of hostilities.[59] Brant denounced the British "no offensive war" policy as a betrayal of the Iroquois and urged the Indians to continue the war, but they were unable to do so without British supplies.

Other events in the New World and Europe as well as changes in the British government had brought reconsideration of British national interest on the American continent. The new governments recognized their priority to get Britain out of its four interconnected wars, and time might be short. Through a long and involved process between March and the end of November 1782, the preliminary peace treaty between Great Britain and America would be made; it would become public knowledge following its approval by the Congress of the Confederation on April 15, 1783. In May 1783, a bitter Brant, when he learned about the treaty of Paris, wrote "England had sold the Indians to Congress".[72] Much to Brant's dismay, not only did the Treaty of Paris fail to mention the Haudenosaunee, but the British negotiators took the viewpoint that the Iroquois would have to negotiate their own peace treaty with the Americans, who Brant knew were a vengeful mood against him.[72] Like all of the Indians who fought for the Crown, Brant felt a profound sense of betrayal when he learned of the Treaty of Paris, complaining that the British diplomats in Paris did nothing for the Indian Loyalists.[73] Nearly another year would pass before the other foreign parties to the conflict signed treaties on September 3, 1783, with that being ratified by Congress on January 14, 1784, and formally ending the American Revolutionary War.

The American Revolutionary War is known to the Haudenosaunee as "the Whirlwind" that led to many of them being exiled from Kanienkeh to Canada, and the decision of Joseph and Molly Brant to be loyal to the Crown as the best way of preserving the Haudenosaunee lands and way of life has been controversial, with many Hadenosaunee historians believing that neutrality would have worked better.[37] However, Paxton noted that after the war the United States imposed treaties that forced the Tuscarora and the Oneida who fought for the United States to surrender most of their land to white settlement; which Paxton used to argue that if all Six Nations had fought for the United States or remained neutral, they still would have lost most of their land.[37] In this context, Paxton maintained that the decision of the Brant siblings in 1775 to support the Crown, which at least promised to respect Haudenosaunee land rights was the most rational under the circumstances.[37]

After the war

In ending the conflict with the Treaty of Paris (1783), Britain accepted the American demand that the boundary with British Canada should revert to its location after the Seven Years' War with France in 1763, and not the revisions of the Quebec Act as war with the colonists approached. The difference between the two lines was the whole area south of the Great Lakes, north of the Ohio River and east of the Mississippi, in which the Six Nations and western Indian tribes were previously accepted as sovereign. For the Americans, the area would become the Northwest Territory from which six-and-a-half new States would later emerge. While British promises of protection of the Iroquois domain had been an important factor in the Six Nations' decision to ally with the British, they were bitterly disappointed when Britain ceded it and acknowledged the territory as part of the newly formed United States. Just weeks after the final treaty signing, the American Congress on September 22, stated its vision of these Indian lands with the Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783; it prohibited the extinguishment of aboriginal title in the United States without the consent of the federal government, and was derived from the policy of the British Proclamation of 1763.

Brant's status as a successful war leader who was popular with the warriors, his relationships with various British officials and his marriage to Adonwentishon, the clan mother of the turtle clan, made him a spokesman for his people, and Brant emerged as a more powerful leader after the war than what he had been during the war.[74] In 1783, Brant consulted with Governor Haldimand on Indian land issues and in late summer of 1783, Brant traveled west and helped initiate the formation of the Western Confederacy. In his speeches during his trip, Brant advocated pan-Indianism, saying that if First Nations peoples would only stick together then the Americans might be held at bay while allowing the Indians to play off the British against the Americans.[75] Brant argued that if all of the Indians held together to negotiate peace with the United States, then they would obtain better terms as he argued the Indians needed to prove to the Americans that they were not "conquered peoples".[75] In August and September he was present at unity meetings in the Detroit area, and on September 7 at Lower Sandusky, Ohio, was a principal speaker at an Indian council attended by Wyandots, Lenape, Shawnees, Cherokees, Ojibwas, Ottawas, and Mingos.[59] The Iroquois and 29 other Indian nations agreed to defend the 1768 Fort Stanwix Treaty boundary line with European settlers by denying any Indian nation the ability to cede any land without common consent of all. At same time, Brant in his talks with Haldimand was attempting to have a new homeland created for the Iroquois.[76] Initially, the new homeland was to be the Bay of Quinte, but Brant decided he wanted the Grand river valley instead.[76] Haldimand did not want to give the Grand river valley to the Iroquois, but with many Haudenosaunee warriors openly threatening to attack the British, whom they accused of betraying them with the Treaty of Paris, Haldimand did not want to alienate Brant, the most pro-British of the chiefs.[77]

Brant was at Fort Stanwix from late August into September for initial peace negotiations between the Six Nations and New York State officials, but he did not attend later treaty negotiations held there with the commissioners of the Continental Congress in October. Brant expressed extreme indignation on learning that the commissioners had detained as hostages several prominent Six Nations leaders and delayed his intended trip to England attempting to secure their release.[59] The Treaty of Fort Stanwix was signed on October 22, 1784, to serve as a peace treaty between the Americans and the Iroquois, but it forced the cession of most Iroquois land, as well as greater lands of other tribes to the west and south. Some reservations were established for the Oneida and Tuscarora, who had been allies of the American rebels.

With Brant's urging and three days later, Haldimand proclaimed a grant of land for a Mohawk reserve on the Grand River in the western part of the Province of Quebec (present-day Ontario) on October 25, 1784. Later in the fall, at a council at Buffalo Creek, the clan matrons decided that the Six Nations should divide, with half going to the Haldimand grant and the other half staying in New York. Starting in October 1784, Brant supervised the Iroquois settlement of the Grand river valley, where some eighteen hundred people settled.[78] At the new settlement of Brant's Town (modern day Brantford, Ontario), Brant had the Mohawks move into two-room log houses while the center of the community was the local Anglican church, St. Paul's.[79] Brant built his own house at Brant's Town which was described as "a handsome two story house, built after the manner of the white people. Compared with the other houses, it may be called a palace." Brant's home had a white fence, a Union Flag flying in front, and was described as being equipped with "chinaware, fine furniture, English sheets, and a well-stocked liquor cabinet".[80] The British historian Michael Johnson described the lifestyle of the Anglophile Brant along the Grand as "something of the style of an English squire".[55] Deeply interested in the Anglican church, Brant used his spare time to translate the Gospel of St. Mark from English into Mohawk.[81] He had about twenty white and black servants and slaves. Brant thought the government made too much over the keeping of slaves, as captives were used for servants in Indian practice. He had a good farm of mixed crops and also kept cattle, sheep, and hogs. At one point he owned 40 black slaves.[82]

Brant was nostalgic for Kanienkeh, and as much possible, Brant tried to recreate the world he had left behind in the Grand river valley.[83] As part of Brant's efforts to recreate Kanienkeh on the Grand, he tried unsuccessfully to persuade all of the Haudenosaunee who gone into exile into Canada to settle on the Grand river valley.[78] Many of the Haudenosaunee who went into exile preferred to take up the British offer on land on the Bay of Quinte, which was further from the United States.[78] Within the Mohawk people, the traditional division between those living in the town of Tiononderoge and those living in the town of Canajoharie persisted, with most of the Tiononderoge Mohawks preferring the Bay of Quinte to the Grand river valley.[78] Brant did not discourage whites from settling around the Grand River valley, and at the beginning of every May, Brant hosted a reunion of Loyalist veterans from New York.[83] At Brant's Town, veterans of Brant's Volunteers, the Indian Department and Butler's Rangers would meet to remember their war services while Brant and other former officers would give speeches to the veterans amid much dancing, drinking and horse racing to go along with the reunions.[83]

Though the Grand River valley had been given to Iroquois, Brant allowed white veterans of Brant's Volunteers to settle on his land.[83] The very first white settlers on the Grand were Hendrick Nelles and his family; the Huff brothers, John and Hendrick; Adam Young and his family, and John Dochsteder, all veterans of the Brant's Volunteers, whom Brant invited to settle.[84] Brant was to trying to recreate the "human geography" of Kanienkeh along the Grand as the families he allowed to settle by the Grand River had all been his neighbours in Kanienkeh before the war.[83] Brant gave leases with an average size of 400 acres to former Loyalists along the Grand river, which became an important source of revenue for the Iroquois, as well recreating the multi-racial and multi-cultural world that Brant had grown up in.[85] Not all the Iroquois appreciated Brant's willingness to allow white veterans to settle in the Grand river valley with two Mohawk veterans, Aaron and Issac Hill threatening at a community meeting to kill Brant for "bringing white people to settle in their lands", which ended with the Hills leaving for the Bay of Quinte.[85] Paxton wrote that European and American writers coming from a patriarchal culture almost completely ignored the clan mothers and tended to give Iroquois headmen, orators, and sachems far more power than what they possessed, and it is easy to exaggerate Brant's power.[86] However, Paxton noted that way in which critics like the Hills attacked Brant as the author of certain policies "suggests that Brant was no empty vessel. Rather, he had transformed his wartime alliances into a broad-based peacetime coalition capable of forwarding a specific agenda".[86] Much to everyone's surprise, Molly Brant did not settle at Brant's Town, instead settling in Kingston.[85] Molly wanted the best education for her eight children, and felt Kingston offered better schools than what were to be found in the settlement run by her brother.[85]

In November 1785, Brant traveled to London to ask King George III for assistance in defending the Indian confederacy from attack by the Americans. The government granted Brant a generous pension and agreed to fully compensate the Mohawk for their losses, but they did not promise to support the confederacy. (In contrast to the settlement which the Mohawk received, Loyalists were compensated for only a fraction of their property losses.) The Crown promised to pay the Mohawk some £15,000 and to pay both Joseph and his sister Molly pensions for their war services.[87] During his time in London, Brant attended masquerade balls, visited the freak shows, dined with the debauched Prince of Wales and finished the Anglican Mohawk Prayer Book that he had begun before the war.[87] He also took a diplomatic trip to Paris, returning to Quebec City in June 1786.

Upon his return, Brant was notably more critical of the British, for instance calling the Colonial Secretary, Lord Sydney, a "stupid blockhead" who did not understand the Iroquois.[88] At the same time, Brant's relations with John Johnson declined with Johnson siding with the Hills against Brant's land policies along the Grand river valley.[88] In December 1786 Brant, along with leaders of the Shawnee, Lenape, Miami, Wyandot, Ojibwa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi nations, met at the Wyandot village of Brownstown and renewed the wartime confederacy in the West by issuing a statement to the American government declaring the Ohio River as the boundary between them and the whites. Nevertheless, despite Brant's efforts to produce an agreement favorable to the Brownstown confederacy and to British interests, he also would be willing to compromise later with the United States.[89] In 1789, a trivial incident strained Brant's relations with the British. Brant attempted to enter Fort Niagara carrying his weapons, and was told by a sentry that as an Indian, he would have to lay down his arms.[88] An indignant Brant refused, saying that as both a Mohawk warrior chief and as a British Army officer, he would keep his weapons, and the commandant of Fort Niagara agreed that Brant would enter with his weapons.[88] Nonetheless, the incident left a sour taste in Brant's mouth as he noted that other officers in the British Army were not asked to remove their weapons when entering a fort. From 1790 onward, Brant had been planning on selling much of the land along the Grand river granted by the Haldimand proclamation and using the money from the sales to finance the modernization of the Haudenosaunee community to allow them equal standing with the European population.[90]

In 1790, after Americans attacked the Western Confederacy in the Northwest Indian War sending General Josiah Harmar on a putative expedition, member tribes asked Brant and the Six Nations to enter the war on their side. Brant refused; he instead asked Lord Dorchester, the new governor of Quebec, for British assistance. Dorchester also refused, but later in 1794, he did provide the Indians with arms and provisions. After the defeat of General Harmar in 1790 at the hands of Little Turtle, the United States became interested in having Brant mediate as the War Secretary Henry Knox wrote several letters to Brant asking him to persuade Little Turtle of the Western Confederacy to lay down his arms.[91] Harmar's defeat proved to the U.S. government that Indians of the Northwest were not "conquered peoples", and it would require a war to bring them under U.S authority.[88] Brant exaggerated his influence with the Western Confederacy in his letters to U.S. officials, knowing if the Americans were courting him, then the British would likewise engage in gestures to keep his loyalty.[91] Brant was attempting to revive the traditional "play-off" system in order to strengthen the position of his people.[92] However, Brant knew that the British were not willing to go to war with the United States to save the Western Confederacy, and his position was not as strong as it seemed.[92]

As a mediator, Brant suggested to the Americans that they cease white settlement in most of the lands west of the Ohio river while advising the Western Confederacy to negotiate with the Americans, saying that after Harmar's defeat they held the upper hand and now was the time to negotiate peace before the Americans brought more military forces into the Old Northwest.[92] Brant also advised the Americans to negotiate with the Western Confederacy as a whole instead with the individual nations and at the same time used his talks with the Americans to impress upon the British that they needed to have respect for First Nations land rights in Upper Canada.[92] The peoples of the Northwest had often had difficult relations with the Iroquois in the past, and were primarily interested in enlisting Brant's aid as a way of bringing the British into the war on their side.[92] In June 1791, Brant was publicly challenged by representatives of the Western Confederacy to "take up the hatchet" against the Americans, and by refusing, his influence, whatever it was, on the Western Confederacy ended forever.[92] Though Brant had warned the Western Confederacy that they were fighting a war that they could not hope to win, in November 1791 Little Turtle inflicted a crushing defeat on the American general Arthur St. Clair, which made Brant appear both cowardly and foolish.[92] After St. Clair's defeat, Little Turtle sent Brant the scalp of Richard Butler, who had one of the U.S. Indian commissioners who negotiated the Treaty of Fort Stanwix, together with the message: "You chief Mohawk, what are you doing? Time was when you roused us to war & told us that if all the Indians would join with the King they should be a happy people & become independent. In a very short time you changed your voice & went to sleep & left us in the lurch".[92] It was widely noted in the Northwest that amongst the victorious warriors who defeated St. Clair were the Shawnee, Miami, Ottawa, Wyandots, Chippewas, Potawatomi, Cherokee, Mingoes and Lepnai, but none were from the Six Nations.[92]

In 1792, the American government invited Brant to Philadelphia, then capital of the United States, where he met President George Washington and his cabinet for the first time. The Americans offered him a large pension, and a reservation in upstate New York for the Mohawks to try to lure them back. Brant refused, but Pickering said that Brant did take some cash payments. Later in 1794, Washington privately told Henry Knox to "buy Captain Brant off at almost any price" in order to avoid further conflict with Brant and the Mohawks.[93] While in Philadelphia, Brant attempted a compromise peace settlement between the Western Confederacy and the Americans, but he failed. In 1793, Brant spoke at a council meeting of the Western Confederacy where he suggested that they accept the American settlements north of the Ohio river while excluding white settlement to the rest of the land west of the Ohio as the price of peace.[94] Brant was outvoted and the assembled chiefs announced that no white settlement west of the Ohio were the only peace terms they were willing to accept.[94] The war continued, and the Indians were defeated in 1794 at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. The unity of the Western Confederacy was broken with the peace Treaty of Greenville in 1795. The defeat of the Western Confederacy led to the Americans losing interest in Brant as a mediator, causing the collapse of his attempts to play the British off against the Americans.[95]

Brant often clashed with General John Graves Simcoe, the governor of Upper Canada.[96] In 1791, following tensions between French-speakers and English-speakers, the province of Quebec had been divided into two new colonies, Lower Canada (modern southern Quebec) and Upper Canada (modern southern Ontario). Brant had begun selling some of the land he owned along the Grand river to British settlers with the intention of investing the profits into a trust that would make the Six Nations economically and politically independent of the British.[97] Simcoe sabotaged Brant's plans by announcing that the Six Nations were only allowed to sell land to the Crown, which would then resell it to white settlers.[98] On January 14, 1793, Simcoe issued a "patent" to the Haldimand proclamation, which stated that the Brant's lands did not extend to the beginning of the Grand river as the Haldimand proclamation had stated, and that the Haudenousaunee did not have the legal right to sell or lease their land to private individuals, and instead were to deal only with the Crown.[99] Brant rejected the Simcoe patent, saying that Simcoe did not have the right to alter the Haldimand proclamation; the question of whether the Iroquois owned all the land to the beginning of the Grand river to its mouth or not is still, as of the 21st century, part of an ongoing land dispute.[99] Simoce justified his "patent" with reference to the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which had forbidden white settlement west of the Ohio river while at the same time giving the Indian tribes living west of the Ohio the right to sell the land only to the Crown, which was the ultimate owner of the land with the Indians merely having the right of "occupancy".[99] Brant disregarded the Simoce's "patent" and in 1795–96 sold blocks of land along the Grand river, receiving some £85,000 sterling together with interest of £5,119 annually.[100] Simcoe disallowed these land sales as illegal and refused to give the buyers land deeds, but he made no effort to evict the buyers, who continued to own the land.[100]

When in the spring of 1795, Brant's son Issac murdered an American deserter named Lowell who had settled in the Mohawk community at Grand River, Simcoe insisted that the Crown was paramount in Upper Canada and Issac Brant would have to face trial for murder in an Upper Canada court, which would try him according to English common law.[98] Brant by contrast insisted that Six Nations were sovereign along their lands on the Grand, and his son would face justice in a traditional Mohawk trial before community elders, denying that Simcoe had the legal right to try any Mohawk.[98] The issue of whether the Six Nations were sovereign along their lands besides the Grand River as Brant insisted or possessing a limited sovereignty subjected to the authority of the Crown as argued by Simcoe had been brought to a head by the question of whether Issac Brant was to be tried by an Upper Canada court or by Mohawk elders, and Brant's actions were motivated than by his desire to protect his son.[98] Simcoe threatened to call out the Upper Canada militia to take Issac Brant by force, when his father refused to turn him over, but was overruled by Lord Dorchester, who told Simcoe that the murder of one deserter from the U.S. Army was scarcely worth a war with the Six Nations, especially as Britain was at war with revolutionary France.[101] Brant had responded to Simcoe's threat to call out the Upper Canada militia that "it would be seen who the most interest with the militia and that the Governor wold not be able to make them Act against him".[90] Most of the white settlers along the Grand River had been given their lands by Brant and many of the men had fought with him during the Revolutionary War, and Brant believed that they would not act against him if it came to a showdown with Simcoe.[90] In 1798, a Moravian missionary who traveled along the Grand river wrote "all the settlers are in a kind of vassalage to him [Brant]".[90]

The issue resolved itself later that year when during the distribution of presents from the Crown to the Iroquois chiefs at Head of the Lake (modern Burlington, Ontario), Issac had too much to drink in the local tavern and began to insult his father.[90] Joseph Brant happened to be in a neighbouring room, and upon hearing what Issac was saying, marched in and ordered his son to be silent, reminding him that insulting one's parents was a grave breach of courtesy for the Mohawk.[90] When an intoxicated Issac continued to insult him, Joseph slapped him across the face, causing Issac to pull out his knife and take a swing at his father.[90] In the ensuring fight, Joseph badly wounded his son by turning his own knife against him, by deflecting the blow which caused the knife to strike Issac's head instead, and later that night Issac died of his wounds.[90] Brant was to be haunted by the death of his son for the rest of his life, feeling much guilt over what he had done.[90]

In 1796, Upper Canada appeared to be on the brink of war with the Mississaugas.[100] In August 1795, a Mississauga chief named Wabakinine had arrived at Upper Canada's capital York (modern Toronto, Ontario) with his family.[100] A British soldier, Private Charles McCuen was invited by Wabakinine's sister into her bed, and neither saw fit to inform Wabakinine of their planned tryst under his roof.[100] When Wabakinine woke up to relieve himself after a night of heavy drinking, he saw an unknown naked white man with his sister, and apparently assuming he had raped her, attacked him.[100] In the ensuring struggle, McCuen killed Wabakinine and, though charged with murder, was acquitted by a jury under the grounds of self-defense.[100] The Mississaguas were incensed with the verdict and threatened war if McCuen was not turned over to them to face their justice, a demand the Crown refused.[102]

Despite their differences with Brant over the land sales on the Grand, the Crown asked him for his help, and Brant visited the Mississaugas to argue for peace, persuading them to accept the verdict, reminding them that under Mississauga law self-defense was a valid excuse for killing someone, and even Wabakinine's sister had stated the sex was consensual and she had tried to stop her brother when he attacked McCuen, screaming she had not been raped, but that he would not listen.[102] Historically, the Haudenosaunee and Mississauga were enemies with the Six Nations, mocking the Mississauga as "fish people" (a reference to the Mississauga practice of covering their bodies with fish oil), and it was a sign of Brant's charisma and charm that he was able to persuade the Mississauga not to go war with the Crown as they had been threatening.[102] Afterwards, Brant was able to form an alliance with the Mississauga with the men of the latter taking to shaving their hair in the distinctive hairstyle of the Mohawk, popularly known as a "mohawk".[102] The governor of Upper Canada, Peter Russell, felt threatened by the pan-Indian alliance, telling the Indian Department officials to "foment any existing Jealously between the Chippewas [Mississauga] & the Six Nations and to prevent ... any Junction or good understanding between these two Tribes".[102] Brant for his part complained to Russell that "my sincere attachment [to Britain] has ruined the interests of my Nation".[103]

In early 1797, Brant traveled again to Philadelphia to meet the British diplomat Robert Liston and United States government officials. In a speech to Congress, Brant assured the Americans that he would "never again take up the tomahawk against the United States". At this time the British were at war with France and Spain. While in Philadelphia, Brant also met with the French diplomat Pierre August Adet where he stated: "[H]e would offer his services to the French Minister Adet, and march his Mohawks to assist in effecting a revolution and overturning the British government in the province."[104] When Brant returned home to Canada, there were fears of a French attack. Peter Russell wrote: "the present alarming aspect of affairs – when we are threatened with an invasion by the French and Spaniards from the Mississippi, and the information we have received of emissaries being dispersed among the Indian tribes to incite them to take up the hatchet against the King's subjects." He also wrote that Brant "only seeks a feasible excuse for joining the French, should they invade this province". London ordered Russell to prohibit the Indians from alienating their land. With the prospects of war to appease Brant, Russell confirmed Brant's land sales. Governor Russell wrote: "The present critical situation of public affairs obliges me to refrain from taking that notice of Capt. Brant's conduct on this occasion which it deserves".[105]

When Brant arrived in York in June 1797 asking for Russell to confirm the land sales along the Grand, the governor asked for the opinion of the executive council of Upper Canada who told him to confirm the land sales.[105] In July 1797 a message from London arrived from the Colonial Secretary, the Duke of Portland, forbidding Brant to sell land along the Grand.[105] Russell offered Brant an annuity that would be equal to the land sales along the Grand, which Brant refused.[105] In a report to London, Russell wrote that Brant "had great Influence not only with his own Tribe, but with the rest of the Five Nations, and most of the neighbuoring Indians; and that he was very capable of doing much mischief".[105] To keep Brant loyal to the Crown, Russell then struck a deal under which the Brant would transfer the land along the Grand river to the Crown, which would sell it to the white settlers with the profits going to the Six Nations.[105] Brant then declared: "[T]hey would now all fight for the King to the last drop of their blood." In September 1797, London had decided that the Indian Department was too sympathetic towards the Iroquois, and transferred authority from dealing with them to the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, Russell, a move that Brant was openly displeased with.[106] The veterans of the Revolutionary War like John Johnson who fought alongside Brant were more sympathetic towards Brant's efforts to maintain independence for his people, which was why London had removed them from dealing with Brant.[106] William Claus, the new man appointed to handle Indian affairs in Upper Canada, wanted the traditional paternal relationship with the Indians as wards of the Crown.[107] On February 5, 1798, some 380,000 acres of land along the Grand belonging to Brant was transferred to the Crown, and Brant hired a lawyer from Niagara named Alexander Stewart to manage the money from the land sale.[105]