Prehistory of Ohio provides an overview of the activities that occurred prior to Ohio's recorded history. The ancient hunters, Paleo-Indians (13000 B.C. to 7000 B.C.), descended from humans that crossed the Bering Strait. There is evidence of Paleo-Indians in Ohio, who were hunter-gatherers that ranged widely over land to hunt large game. For instance, mastodon bones were found at the Burning Tree Mastodon site that showed that it had been butchered. Clovis points have been found that indicate interaction with other groups and hunted large game. The Paleo Crossing site and Nobles Pond site provide evidence that groups interacted with one another. The Paleo-Indian's diet included fish, small game, and nuts and berries that gathered. They lived in simple shelters made of wood and bark or hides. Canoes were created by digging out trees with granite axes.

The weather warmed and forest grew more dense with next period of the Archaic people (8000 B.C. to 500 B.C.). Although they were also hunter-gatherers, they did not travel as far for food and began to live longer periods of time in one place. They dug pits to store food and built studier lodging. Tools, like spear-throwers, were more sophisticated. Base camps were established for winter lodging. The Glacial Kame culture, a late Archaic group, traded for sea shell and copper with other groups and were used as a sign of prestige within the group, for respected healers and hunters. The objects were buried with their owners. By the Woodland period (800 B.C. to A.D. 1200) of the Post-Archaic Period, people lived in villages, developed a rich ritual and artistic life, began building earthworks and mounds, some of which were used for burial. While they still hunted and gathered food, they cultivated crops. The Adena and Hopewell cultures flourished during the Early and Middle Woodland periods, respectively. The population of Woodland people expanded dramatically and groups lived in larger villages with defensive walls or ditches built for protection. Ritual and artistic endeavors waned during the Late Woodland period, as did trading with other groups. There were not new earthworks or mounds during this later period.

During the late prehistoric period (A.D. 900 to 1650), villages were larger, often built on high ground, near a river, and often surrounded by a wooden stockade. Earthworks returned during this period, but were not built in the frequency that they were during the Woodland period. The Serpent Mound, the country's largest effigy mound, was created by the Fort Ancient culture. Maize became a staple of their diet, while squash and beans were cultivated. The centers of villages were the locations where ceremonial rituals were conducted.

The Early Contact period (1600–1750) began when Ohio tribes met Europeans, but they had begun to acquire European trade items in as much as a hundred years before they met through trade with other Native American groups. They traded for glass beads, brass, and copper items. Direct contact began in the late 17th century when traders, white explorers, and settlers came to Ohio. With them came smallpox which devastated Native American tribes, particularly affecting children and the elderly.

Background

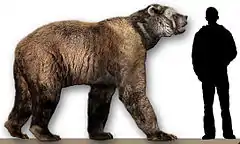

Humans and animals migrated over the Bering Strait to populate the Americas. They then traveled over hundreds of years into what is now the United States. The animals that came from Asia include mastodons, mammoths, elk, bison, caribous, and muskox.[1] Some of the earliest humans may have migrated through Canada to the Great Lakes region and then south from there, according to some archaeologists. During the time of the migration and until about 7,500 years ago, the Great Lakes extended south as far as Allen County, Ohio.[1]

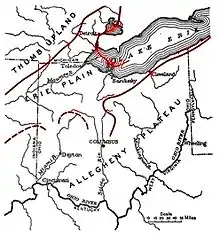

The glaciers left bogs and small lakes and the flat Erie Plain along the Lake Erie shore. The Glaciated Allegheny Plateau southeast of Cleveland included steep Appalachian Mountains foothills that thousands of years ago had a dense Beech-Maple forest. By the time that Europeans made contact with Native Americans, the Erie Plain had wide river estuaries, coastal marshes, small prairies, and a mixed oak forest. The Central Till Plain had areas of native beech-oak-hickory woodland and "rolling terrain of glacial soils".[2]: 1

Paleo-Indian period

The paleolithic period (13000 B.C. to 7000 B.C.) occurred during the last centuries of the Ice age. The native people of Ohio descended from those who crossed the Bering Strait land bridge from Asia to North America. The Paleo Indians are the earliest hunter-gatherers that ranged across what is now the state of Ohio. Their diet was based upon the food that they hunted—evidenced by distinctive spear points—fished, and gathered. Mammoth and mastodon, now extinct, were the big game animals that they hunted. They also hunted small game and deer. Fish was in their diet, as was fruit and nuts that they gathered seasonally.[3] Bones from the Burning Tree Mastodon indicate that Paleo-Indians hunted and butchered the mastodon. Because evidence of Paleo-Indians is generally limited to the finding of stone tools, this has been considered a "one of the most spectacular Paleoindian finds in Ohio."[4]

Clovis culture

.jpg.webp)

The Clovis culture (9500 to 8000 B.C.) is the earliest known Paleo Indian culture in Ohio. They are named by the type of spear point that they used, the clovis point, which were discovered by archaeologists near Clovis, New Mexico. The points were attached to spears for hunting[3] and are believed to have been used to hunt mastodons and mammoths.[5] They ranged across the land for food and lived in shelters made of wooden pole covered with hides or tree bark. Their diet consisted of small and large game animals that they hunted, fish, berries and nuts. They created tools from flint, particularly Flint Ridge flint from Licking County and Upper Mercer flint from Coshocton County.[3] They used flint because it was hard, durable, easy to flake when heated up, and could be made to have very sharp edges.[6] Their tools included scrapers, knives, and spear points.[2]: 1

Culturally, there was a laissez-faire attitude. People could remain with a group of people, join another group of people, or split off from groups. If they were particularly skilled in a certain area, like healing, hunting, or another important skill, they earned the respect of the tribe. Elders were respected for their knowledge and experience. They usually, though, did not have chiefs.[3] Most Native American people descended from the Clovis people.[7]

Clovis artifacts dated to 13,000 years ago were found at the Paleo Crossing site in Medina County provides evidence of Paleo-Indians in northern Ohio and may be the area's oldest residents and archaeologist Dr. David Brose believes that they may be "some of the oldest certain examples of human activity in the New World."[7] Small bands of hunters used the four acre site as a place to meet up with one another and exchange information, perform ceremonial rituals, and plan hunts for big game.[2]: 2 The site contains charcoal recovered from refuse pits. There were also two post holes and tools that were made from flint from the Ohio River Valley in Indiana, 500 miles from Paleo Crossing, which indicates that the hunter-gatherers had a widespread social network and traveled across distances relatively quickly.[7] The 22-acre Nobles Pond site in Stark County was a larger meeting place for bands of hunters, with a large collection of tools made from Ohio flint.[2]: 2 [4]

Other early sites are the Sandy Springs Site in Adams County, Sheriden Cave in Wyandot County, and the Welling site in Coshocton County.[8]

Archaic

Archaic people (8000 B.C. to 500 B.C.) lived in a warmer climate after the end of the Ice Age and with thicker forests than their ancestors.[9] The climate was similar to present-day Ohio in that the climate evolved into having four seasons.[10] They used technology in a more sophisticated manner, and the same openness for members to join other groups of people or set out on their own. Over time, they began to live longer periods of time in one place, dug pits to store food and built studier lodging.[9] Traveling for food, they hunted turkeys, deer, waterfowl, and passenger pigeons. They also fished and gathered berries, acorns and hickory nuts.[10] As the climate changed, there were different foods available, resulting in dietary changes.[11]

This period is divided up by archaeologists into Early (10,000-8,000 before present) and Middle Archaic cultures (8,000-5,000 before present) because there are different technological and cultural characteristics between the two groups. Early Archaic groups were smaller, but as the population increased they lived in larger groups. In the Middle Archaic period there was an increased variety of food.[10] Later in the Archaic period, people developed trade routes which introduced new goods and ideas and bands became more culturally diverse.[11]

The Archaic people continued to make their tools from flint, but they made a wider range of tools.[9] The stone tools of the Paleo-Indians disappeared.[2]: 3 The Early Archaic group had more spear points.[10] New stone tools were made of the same flint to chert, but included spear points with large corner- and side-notches and large chert knives.[2]: 3 Their shapes varied depending upon how they were to be used and some may have been attached to short handles to use like knives or to long spears for hunting.[12] The Middle Archaic group created a wide range of tools, including knives, grinding tools and stones, scraping tools, plummets, and net sinkers.[10] Mortars and pestles were used to grind food, like acorns, hickory nuts, walnuts, seeds, tubers, and rootes.[2]: 3

They made spear-throwers, or atlatls, that could be thrown with greater force and at a farther distance and with more accuracy.[9][11] Bannerstones made of slate were attached to the shafts of the spear-thrower.[2]: 3 They made axes out of granite, which they used to cut down trees and hollow out canoes or build houses.[9][2]: 3 Slate was carved and polished and used as decorations or weights.[9] They made jewelry, weights, and sinkers by grinding stone.[11] They created base camps for the winter.[10] A day in the life of an Archaic family member could include building a fire, fishing, grinding nuts for storage, and carving out a dugout canoe.[10]

The last several thousands of years of the Archaic period saw a dramatic increase in the number of Archaic sites, indicating a rise in the population. There have also been a larger number of stone tools found during this period, including flake tools, drills, knives, scrapers, projectile points, and tools for grinding food. Fishing tackle, such as harpoon heads, net sinkers, and bone hooks, indicated that they were fishing in Lake Erie and in rivers. With climate change, beech-maple forests were well established.[2]: 3, 5

Archaic sites include along the Maumee River or at Dupont Site, Weilnau Site, Raisch-Smith Site, [10] Bowman Site in Montgomery County, and the Stephan Site in Darke County.[8]

Glacial Kame culture

The Glacial Kame culture, a late Archaic group, traded for sea shell and copper with other groups and were used as a sign of prestige within the group, such as respected healers and hunters. The objects were buried with their owners.[9]

Post Archaic

Woodland period

.jpg.webp)

People from the Woodland Period (800 B.C. to A.D. 1200) lived in small villages of several households, with more permanent houses. They domesticated plants and grew sunflower, maygrass, squash, lamb's quarter and erect knotweed. This meant a very different way of life than relying on hunting and gathering. Another characteristic is that they made pottery. Burial mounds were used to bury the dead. People of the Hopewell and Adena cultures created elaborate earthworks in geometric patterns, like the Newark Earthworks, earthworks found near Chillicothe at the Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, and earthworks at Portsmouth and Marietta.[13] They embraced artistic and ritual endeavors, creating works with materials obtained due to larger trade networks.[14]

The cultures of the woodland period are defined by how they lived, rather than a connection with a particular contemporary cultural or ethnic group.[15] Except for the Hopewell, people of the Early and Middle Woodland periods did not have a dramatic change in their lifestyles, but they all had a richer cultural, architectural, and artistic life.[15]

Small villages or substantial campsites were established in northeast Ohio the Middle Woodland period, about 2,000 years ago. Built by rivers, they were located on high ridge-tops with steep-sided cliffs, making them difficult to access. Some of them were also surrounded by ditches and earthen walls. Some did not seem to be lived in much, while others showed evidence of long-term use by the presence of middens, human burials, pottery, food storage pits, and cooking pits. Leimbach Fort in Lorain County and Seaman's Fort in Erie County are examples of settlements that had long-term use. The Adena and Hopewell cultures had sites that were used just for ceremonial purposes.[2]: 6

During the Woodland period, people began to create crude pottery of soapstone by carved the stone. Other pottery was created from crushed granite rocks and clay from local rivers. When the pottery was formed, fabric was pressed against the inside and outside of the pot before the pot dried and was fired in a shallow pit. The traces of fabric left in the pottery shows that people were creating textiles, and likely mats, cordage, and woven baskets. Pots were used to store food, protect it from burrowing animals, and for cooking food over a fire.[2]: 6

The population grew rapidly[16] so that people of the Late Woodland Period (A.D. 600 to A.D. 1200) lived in larger and more permanent villages than those of the Adena and Hopewell people and they built defensive walls or ditches around their villages.[17][16] This is believed to have been due to increased regional conflict among the villages.[16] It marked an end to a culture focused on artistic expression and earthworks construction.[16] They relied more on food that they grew—like sunflower, knotweek, goosefoot, and maygrass[16]—and began growing maize about A.D. 800.[17] Food was stored in large pottery jars.[16]

Projectile points became thinner and smaller–either with no notches or finely notched triangular points for bow and arrows,[2]: 6 which could be used for hunting or as a weapon. It marks the decline of the Hopewell culture and cultures began to diversify in different areas. They stopped trading over long distance, and stopped importing large quantities of mica and obsidian. The building of large earthworks generally stopped in the Woodland period, but some buried their dead in the Hopewell earthworks.[17]

Adena culture

The Adena culture—found in southern Ohio and neighboring states—flourished during the Early Woodland period. People of the Adena culture were artistic and had created pipes and earthworks as part of ceremonial rituals. They created elaborate siltstone pipes and other items for ceremonial and burial practices. They constructed earthworks, like conical burial mounds and circular enclosures—some of the earliest earthworks built in Ohio.[14]

There were also people in northern Ohio who lived similarly to the Adena culture, but their earthworks were oval enclosures called forts and walls along bluffs. They did not create large earthen mounds.[14]

Hopewell culture

The Hopewell culture—the center of which lies in Ohio—flourished during the Middle Woodland period. They are known for their architectural and artistic endeavors, as well as having a "complex ceremonial life unrivaled in North America at the time." They spent up to thousands of hours to create large-scale geometric earthworks, meant to fit specific pre-conceived site plans which might have been planned based upon other earth mounds and based on the landscape. Alignment with the moon and stars may also have been a consideration.[15]

Goods were made from copper that were imported from hundreds of miles away. They created a wide range of artistic artifacts, including figurines, decorated pottery, effigy pipes, copper plates, mica cut-outs, and bone adornments.[15]

Mounds

| Mound | Location | Date | Culture | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carl Potter Mound | Champaign County, Ohio | ? | ? | Also known as the "Hodge Mound II", it is located in southern Champaign County, Ohio near Mechanicsburg,[18] it lies on a small ridge in a pasture field in southeastern Union Township. |

| Conus | Marietta Earthworks, Marietta, Ohio | 100 BCE to 500 CE | Adena culture | The conical Great Mound at Mound Cemetery is part of a mound complex known as the Marietta Earthworks, which includes the nearby Quadranaou and Capitolium platform mounds, the Sacra Via walled mounds (largely destroyed in 1882), and three enclosures.[19] |

| Dunns Pond Mound | Logan County, Ohio | ca. 300 to 500 CE | Ohio Hopewell culture | Located in northeastern Ohio near Huntsville,[18] it lies along the southeastern corner of Indian Lake in Washington Township. In 1974, the mound was listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a potential archeological site, with much of its significance deriving from its use as a burial site for as much as nine centuries. |

| Miamisburg Mound | Miamisburg, Ohio | 800 BCE to 100 CE | Adena culture | The largest conical mound in the state of Ohio, constructed by the Adena culture on a 100-foot-high bluff, the mound measures 877 feet (267 m) in circumference and its height is 65 feet (20 m). |

| Mound City | Chillicothe, Ohio | 200 BCE to 500 CE | Ohio Hopewell culture | Located on Ohio Highway 104 approximately four miles north of Chillicothe along the Scioto River, it is a group of 23 earthen mounds. Each mound within the Mound City Group covered the remains of a charnel house. After the Hopewell people cremated the dead, they burned the charnel house. They constructed a mound over the remains. They also placed artifacts, such as copper figures, mica, arrowheads, shells, and pipes in the mounds. |

| Reservoir Stone Mound | Licking County, Ohio | AD 85 to 135 | Probably Adena culture | Also known as the Jacksontown Stone Mound, the central, stone-covered structure was largely destroyed by the removal of stones to construct the Licking Reservoir and by a 19th-century treasure-hunter. Around the edge of the large stone mound were a number of earthen mounds, some of which contained burials. [20] |

| Newark Earthworks | Licking County, Ohio | The Newark Earthworks includes the Octagon and Great Circle Earthworks.[8] | ||

| Serpent Mound | Adams County, Ohio | The effigy mound, on a plateau above Brush Creek, is 1,330 feet (410 m) long.[8] | ||

Late prehistoric

During the late prehistoric period (A.D. 900 to 1650), villages were larger, often built on high ground, and often surrounded by a wooden stockade.[21][22] There were more permanent settlements established in river valleys. People lived in village from late spring to early fall, and some lived in villages permanently, particularly by 800 years ago.[2]: 8–9 Plazas were placed in the center of villages and was where they conducted rituals. In other places, large cities were established, such as in the Southeastern United States and the Mississippi Valley. Cahokia in Illinois was the largest city of the Late prehistoric period, also called the Mississippian Period.[21] The dead were buried in effigy mounds or in graves surrounding the village plaza. Alligator Effigy Mound and Serpent Mound may have been created to honor important spirits.[21]

Maize became a staple of their diet[22] and squash and beans were added to their diet. Hunting, fishing, and gathering wild plants also provided food for the village. The term Late prehistoric is also a grouping for the various Native American cultures before contact by Europeans.[17][21] The villages had one or two leaders. A war chief may be a village's leader.[21] This period saw a shift in ritual practices.[22]

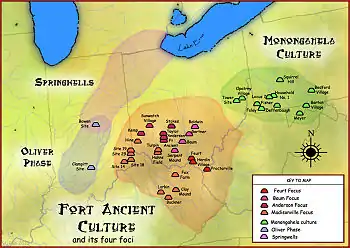

Several cultures were prominent during this period, including the Monongahela, Whittlesey, Sandusky and Fort Ancient cultures.[21]

Whittlesey culture

The Whittlesey culture has been studied most extensively due to number of sites, such as Fairport Harbor, Reeves, South Park, and Tuttle Hill. There is also evidence of house walls and cooking and storage pits. There is a wealth of artifacts and material, like pottery, arrow points, and debris. Charred remains of squash, beans, and maize are evidence that they cultivated these foods. Bones and clam shells were found that showed that they continued to hunt and fish for food. The Whittlesey sites were selected with defense in mind, set on hilltops and with stockades, ditches, or earthen walls to surround the village.[2]: 8–9

Fort Ancient culture

The Fort Ancient culture—of southern Ohio and northern Kentucky—flourished during the Late Prehistoric Period. Rectangular or circular houses surrounded a plaza area. Although they did not build earthworks in the same frequency as the Hopewell culture, they built several large earthworks, like the Serpent Mound, the country's largest effigy mound. They made petroglyphs, like the Leo Petroglyph that has images of footprints, people, and animals. Stone tools were made in shapes particular to their culture, like triangular arrow points and pentagonal flint knives.[22]

Early Contact period

The Early Contact period (1600–1750) began when Ohio tribes met Europeans, but they had begun to acquire European trade items in as much as a hundred years before they met through trade with other Native American groups, perhaps from the Appalachian Mountains or the southern shore of the Great Lakes. They traded for glass beads, brass, and copper items from Europeans. They also were influenced by Spanish settlers and explorers from the south. [23]

Direct contact began in the late 1600s when traders, white explorers, and settlers came to Ohio. The native peoples from Ohio had not been subjected to, and had not immunity for European diseases, like small pox, which was devastating to the population of Native Americans. Children and the elderly were particularly affected.[23]

Conflicts between the Iroquois and the French resulted in expansion of Iroquois territory into Ohio after they won battles with the French.[23] About 350 years ago, people of the Whittlesey culture abandoned Ohio. At that time, during the Beaver Wars, the Iroquois raided other native groups settlements, and the Whittlesey people may have been victims of the Iroquois. By 1650, there were no native inhabitants in northern Ohio.[2]: 8–9 Other local populations were also pushed out of the state. Many native people returned after the conflicts subsided. The Native American groups later in Ohio included the Huron, Wyandot, Miami, Delaware, Ottawa, Shawnee, Mingo, and Erie people.[23]

In the 1800s, Native Americans were pushed out of Ohio and westward across the Mississippi River.[2]: 9

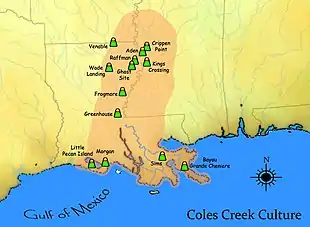

Prehistoric culture maps

Nation du Chat (Erie people) region

Nation du Chat (Erie people) region

See also

- Archaeological sites on the National Register of Historic Places in Ohio

- History of Ohio

- Indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Paleontology in Ohio

- Settlement of the Americas

- Timeline of North American prehistory

- Organizations

References

- 1 2 "Shelby County Historical Society - Indians - About the Paleo-Indians". www.shelbycountyhistory.org. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Brian G. Redmond, PhD., Curator of Archaeology (March 2006). "Before the Western Reserve: An Archaeological History of Northeast Ohio" (PDF). The Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 "Paleoindian Period - Ohio History Central". ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- 1 2 "Paleoindian Period (14,000 - 10,000 Before the Present". National Park Service. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ↑ "Clovis Spear Points - Ohio History Central". ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ↑ "Flint - Ohio History Central". ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- 1 2 3 "Paleo Crossing: Clues to Ohio's Earliest Residents". Explore Member Magazine. Vol. 3, no. 2. Summer 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2020 – via Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Archaeological Society of Ohio - Archaeological Sites of Ohio". www.ohioarch.org. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Archaic Period - Ohio History Central". ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Early/Middle Archaic Culture - Ohio History Central". ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 "Archaic Period (10,000 - 2,500 Before the Present)". National Park Service. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ↑ "Archaic Spear Points and Knives - Ohio History Central". ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ↑ "Woodland Period - Ohio History Central". ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- 1 2 3 "Early Woodland Period (2,500 - 2,000 Before the Present)". National Park Service. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 "Middle Woodland Period (2,000 - 1,500 BP)". National Park Service. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Late Woodland Period (1,500 - 1,100 Before the Present)". National Park Service. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 "Late Woodland Cultures - Ohio History Central". ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- 1 2 "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- ↑ Woodward, Susan L.; McDonald, Jerry N. (1986). Indian Mounds of the Middle Ohio Valley: A Guide to Mounds and Earthworks of the Adena, Hopewell, Cole, and Fort Ancient People. Blacksburg, Virginia: McDonald & Woodward Publishing. pp. 252–257. ISBN 978-0939923724.

- ↑ Lepper, Bradley T., 2016, "A RADIOCARBON DATE FOR A WOODEN BURIAL PLATFORM FROM THE RESERVOIR STONE MOUND (33LI20), LICKING COUNTY, OHIO," Journal of Ohio Archaeology 4:1-11

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Late Prehistoric Period - Ohio History Central". ohiohistorycentral.org. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 "Late Prehistoric Period (1,100 - 400 Before the Present)". National Park Service. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 "Early Contact Period (400 - 250 Before the Present)". National Park Service. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

Further reading

- General history or prehistory

- Kern, Kevin F.; Wilson, Gregory S. (2013-08-14). Ohio: A History of the Buckeye State. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-54832-5.

- Paleoindian Period

- The First Americans: In Pursuit of Archaeology’s Greatest Mystery. James M. Adovasio with Jake Page, Random House, Inc., New York, New York, 2002.

- The First Discovery of America: Archaeological Evidence of the Early Inhabitants of the Ohio Area. William S. Dancey, Editor, The Ohio Archaeological Council, Columbus, 1994.

- Search for the First Americans. David Meltzer, Smithsonian Books, Washington, D.C., 1993.

- Journey to the Ice Age: Discovering an Ancient World. Peter Storck, University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver, 2004.

- Archaic Period

- Archaic Transitions in Ohio and Kentucky Prehistory. Olaf H. Prufer, S. E. Pedde, and R. S. Meindle, editors, Kent State University Press, Kent, 2001.

- Koster: Americans in Search of Their Prehistoric Past. S. Struever and F. Antonelli, Holton New American Library, New York, 1979.

- Early Woodland Period

- Mounds for the Dead. Don W. Dragoo, Annals of the Carnegie Museum, No. 37, Pittsburgh, 1963.

- A Quiet Revolution: Origins of Agriculture in Eastern North America. Ruth O. Selig, in Anthropology Explored: the Best of Smithsonian Anthro Notes, edited by R. O. Selig and M. R. London, pp. 178-192, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C., 1998.

- The Mound Builders. Robert Silverberg, Ohio University Press, Athens, Ohio, 1968 (abridged version, 1986).

- Indian Mounds of the Middle Ohio Valley: A Guide to Mounds and Earthworks of the Adena, Hopewell, Cole, and Fort Ancient People. Susan L. Woodward and Jerry N. McDonald, The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company, Blacksburg, Virginia (2002, 2nd Edition). [This is an excellent guide for those who wish to visit Ohio's publicly accessible archaeological sites].

- Middle Woodland Period

- Fort Ancient: Citadel, Cemetery, Cathedral, or Calendar? Jack Blosser and Robert C. Glotzhober, The Ohio History Connection, Columbus, 1995.

- The Newark Earthworks: A Wonder of the Ancient World. Bradley T. Lepper, The Ohio History Connection, Columbus, 2002.

- People of the Mounds: Ohio's Hopewell Culture. Bradley T. Lepper, Eastern National, Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, revised edition, 1999.

- A View from the Core: A Synthesis of Ohio Hopewell Archaeology. Paul J. Pacheco, Editor, The Ohio Archaeological Council, Columbus, 1996.

- Indian Mounds of the Middle Ohio Valley: A Guide to Mounds and Earthworks of the Adena, Hopewell, Cole, and Fort Ancient People. Susan L. Woodward and Jerry N. McDonald, The McDonald & Woodward Publishing Company, Blacksburg, Virginia (2002, 2nd Edition). [This is an excellent guide for those who wish to visit Ohio’s publicly accessible archaeological sites].

- The Hopewell Mound Group: Its People and Their Legacy. An Interactive Educational Resource Tool, The Ohio History Connection, Columbus, 1995.

- Earthworks: Virtual explorations of ancient Newark, Ohio. An Interactive virtual tour of the Newark Earthoworks, CERHAS, The University of Cincinnati, 2005.

- Late Woodland Period

- Late Woodland Societies: Tradition and Transformation Across the Midcontinent. T.E. Emerson, D.L. McElrath, and A. C. Fortier, editors, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2000.

- The Late Woodland Period in Southern Ohio: Basic Issues and Prospects. Mark F. Seeman and William S. Dancey in Tradition and Transformation Across the Midcontinent, T.E. Emerson, D.L. McElrath, and A.C. Fortier, editors, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 2000.

- Late Prehistoric Period

- Societies in Eclipse: Archaeology of the Eastern Woodlands Indians, A.D. 1400-1700. David S. Brose, C. Wesley Cowan, and R.C. Mainfort, Jr., editors, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C., 2001.

- First Farmers of the Middle Ohio Valley: Fort Ancient Societies, A.D. 1000-1670. C. Wesley Cowan, Cincinnati Museum of Natural History, Cincinnati, 1987.

- Cultures Before Contact: The Late Prehistory of Ohio and Surrounding Regions. Robert A. Genheimer, Editor, The Ohio Archaeological Council, Columbus, 2000.

- Ohio’s Alligator. Bradley T. Lepper, Timeline, 18(2):18-25, The Ohio History Connection, Columbus, 2001.