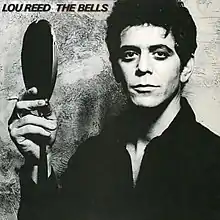

| The Bells | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | May 1979 | |||

| Recorded | 1979 | |||

| Studio | Delta Studios (Wilster, West Germany) | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 40:37 | |||

| Label | Arista | |||

| Producer | Lou Reed | |||

| Lou Reed chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Lou Reed studio album chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from The Bells | ||||

| ||||

The Bells is the ninth solo studio album by American rock musician Lou Reed, released in May 1979 by Arista Records.[2] It was recorded in binaural sound at Delta Studios in Wilster, West Germany. Production was handled by Reed with Michael Fonfara serving as executive producer. Three out of nine songs on the album are the product of a short-lived writing partnership between Reed and Nils Lofgren. More of the team's work appeared on Nils' solo studio album Nils, released the same year. Lofgren released his version of "Stupid Man" as "Driftin' Man" on Break Away Angel (2001).[3] Lofgren resurrected five songs he wrote with Reed in the late 70s on Blue with Lou (2019).[4]

A jazz-rock and art rock album, The Bells features contributions from Michael Fonfara, Ellard "Moose" Boles, Don Cherry, Marty Fogel and Michael Suchorsky. The album peaked at No. 13 in New Zealand, No. 44 in Sweden, No. 58 in Australia, and No. 130 in the United States, and received mixed reviews from music critics.

Recording

Following a short European tour, Reed recorded The Bells in binaural sound at Delta Studios, a studio in Wilster, West Germany owned by Manfred Schunke, with trumpeter Don Cherry and the Everyman Band.[5] The pastoral studio was based in a converted farmhouse with housing for the musicians, a communal dining hall and, according to saxophonist Marty Fogel of the Everyman Band, "a place to hang out and drink Johnnie Walker Black. And then there was the recording facility, which was really high-tech, but it was in the middle of farm country."[5] Reed said: "I mastered the art of recording known as 'capture the spontaneous moment and leave it at that'. The Bells was done like that, those lyrics were just made up on the spot and they're absolutely incredible. I'm very adept at making up whole stories with rhymes, schemes, jokes".[6]

In a 1996 interview with Ian Penman of The Guardian, Reed noted that the binaural sound experiment was unsuccessful for him, adding that "the process worked but it didn't translate to vinyl AT ALL. Not only didn't I get the effect – which I still think is one of the most amazing things I've ever heard in my life when it's done right – not only didn't it translate but it also didn't record things so they sounded very good either, which was disappointing."[7]

Composition

The Bells has been described as a jazz-rock fusion album.[8] According to Jazz Times writer Aiden Levy, it is an eclectic jazz rock and art rock album which "[blends] jazz, disco and a deeply personal songwriting ethos, with no eye toward a potential market."[5] The album is also characterised by its reliance on keyboards.[9] Reed joked: "If you can't play rock and you can't play jazz, you put the two together and you've really got something."[10] Biographer Anthony DeCurtis wrote that "[t]he album's jazz components, and its descent into atmospheric noises and effects, especially on the title track, are part of its intense experimental impulses." He added that the album moves between more commercial material and music that "[pushes] well beyond the boundaries of mainstream acceptability."[10]

"Stupid Man" is characterised by piano.[11] "Disco Mystic" has been described as a "funk workout" typical of the time[9] and "an exercise in churning R&B".[8] Containing saxophone from Marty Fogel,[11] it is effectively an instrumental, with the title "chanted in a deep, mock-impressive voice".[12] "I Want to Boogie with You" is a straight funk song[11] on which Reed portrays "a soulful seducer".[12] "With You" contains "improvised interpolations" from Fogel and Cherry." According to Fogel: "I did a little horn arrangement for myself and Don, and maybe there would be two beats at the end of the measure, and when we were rehearsing the tune, Don was playing this free stuff in those two beats. I looked at him and I go, 'What are you doing?' And he said, 'Whenever you get an opportunity to take it out, you've got to take it out.' So that's what we did."[5] "City Lights" is a tribute to Charlie Chaplin, sung in a "bass-goon voice"[12] One critic describes Reed's singing as "a muted croak, so deep that it's hardly recognisable. Ghoulish and...funny."[11]

On "All Through the Night", Reed evokes a "desperate carouser"; the song also contains "self-consciously sleazy conversation going on in the background", similarly to Reed's earlier song "Kicks" (1975).[12] "Families" has been dubbed "a meditation on the dysfunctional American nuclear family".[5] On the closing title track, notionally inspired by Edgar Allan Poe's poem of the same name,[5] Reed uses a guitar synthesizer while Don Cherry provides free jazz trumpet work.[9] Containing an "atmospheric, droning quality",[13] the track has been described as "an atmospheric nine-minute free-jazz collective improvisation",[5] and a "slow, dark whirlpool".[8] Some of its lyrics were improvised by Reed in the studio; the musician also asked Cherry to interpolate a portion of Ornette Coleman's "Lonely Woman" (1959) in the song's intro.[5] According to critic Mark Deming, the track is "both a brave exploration of musical space and a lyrically touching sketch of loss and salvation."[9]

Release

The Bells was Reed's fourth album in his five-album deal with Arista. However, according to DeCurtis, the album contained no single material, "and whatever hopes Reed and [label head] Clive Davis had once entertained about Reed's reaching a wider audience had been buried." According to Reed, Davis sent him a letter explaining that he believed the album was unfinished and needed further work, a suggestion which the musician dismissed, but in doing so, he believed the label underpromoted the record. He said: "It was released and dropped into a dark well."[10] In a 1996 interview with Penman, Reed said that the album's master tapes no longer existed, requiring him to buy a copy from "one of those speciality record stores" and "put it through a computer program" for preservation/remastering.[7]

Critical reception

Contemporary reviews

According to Aiden: "Though not everyone understood or appreciated Reed's foray deeper into jazz- and art-rock, Lester Bangs, despite their fraught history, concluded that his career had finally reached an apotheosis."[5] In his contemporary review for Rolling Stone, Bangs wrote, "With The Bells, more than in Street Hassle, perhaps even more than in his work with The Velvet Underground, Lou Reed achieves his oft-stated ambition—to become a great writer, in the literary sense". He also praised Reed's band, saying they provide "the only true jazz-rock fusion anybody's come up with since Miles Davis' On the Corner period."[8] The Village Voice critic Robert Christgau said that Reed "is as sarcastic as ever", but added that "the music's jazzy edge and warmly traditional rock and roll base" afford Reed a more "well-rounded" character than on Street Hassle, adding: "The jokes seem generous, the bitterness empathetic, the pain outfront, the tenderness more than a fleeting mood. And the cuts that don't work-there are at least three or four-seem like thoughtful experiments, or simple failures, rather than throwaways. I haven't found him so likable since The Velvet Underground."[14]

Jon Savage of Melody Maker praised the production and musicianship, though felt Reed's "personal inspiration is drying up" in both the lyrics and music. He described The Bells as "a more consistent work throughout, yet at present lacks anything so memorable or cutting as Street Hassle."[11] In his review for New Musical Express, Charles Shaar Murray believed that the album is instantly notable for Reed having eschewed his typical singing voice for "a more demonstrative, expressive and black-influenced style." However, he believed this resembled "someone attempting an impression of David Bowie and failing." He praised "Disco Mystic" and "Families" but believed the overall instrumental sound to be "heavy, turgid, synth-laden, indigestible, lumpy" and the vocal sound "quavery, unstable, unsteady, insubstantial".[12] Don Snowden of The Los Angeles Times dismissed The Bells as "a dismal, turgid effort." He wrote: "He's broken with past tradition by collaborating with rocker Nils Lofgren, free-jazz trumpeter Don Cherry and various band members on the material, but the experiment doesn't work. The music is positively lethargic and uninspired and the lyrics – while retaining the unflinching emotional honesty of Reed's best work – merely revisit old turf without providing new insights."[13]

Retrospective assessment

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| The Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| The Great Rock Discography | 5/10[18] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Select | |

| The Village Voice | B+[14] |

Reviewing the 1992 reissue, Dave Morrison of Select commented that Reed was "not at his best" in the mid-late 1970s, adding that "The Bells saw his music disappearing down the pan. Even self-parody is barely achieved in these half-assed songs played by a bunch of dullards, with Lou sounding painfully uninspired."[20] The Rough Guide to Rock contributor Roy Edroso ted that Reed's feud with Arista was reflected in The Bells, an album he deemed to comprise "mostly grooves and riffs built around slabs of inchoate feeling (sometimes effectively, as with the ruined reunion of 'Families'). At decade's end, Reed appeared to be in a mood as bad as his Metal Machine Music era."[21]

In a positive assessment, the Chicago Tribune reviewer Greg Kot described the album as "[a] jazzier, warmer detour" for Reed.[16] AllMusic's Mark Deming wrote that The Bells musically represented a slight step back for Reed from the tormented Street Hassle to "the more listener-friendly, keyboard-dominated sound of Rock and Roll Heart", but considered the lyrics to move the singer "away from the boho decadence of most of his 1970s work and toward a more compassionate perspective on his characters". Considering the album to have aged well, he concluded that it "gains depth with each playing and now sounds like one of Reed's finest solo efforts of the 1970s."[15]

In his book The Great Rock Discography, Martin C. Strong said that, following the "tedious" Live: Take No Prisoners (1978), Reed "started to show uncharacteristic signs of maturity in both his music and lyrics" with The Bells and its follow-up Growing Up in Public (1980).[18] Critic Tom Hull considered The Bells to potentially be Reed's "most ambitious work", adding: "Returning to Coney Island Baby's confessional mode and incorporating a subtle jazz influence, Reed makes one of his strongest musical statements. Reed's razor-edge frankness is riveting throughout."[22] In The Rolling Stone Album Guide, Hull deemed the record to be "another twist" in Reed's career: "cut with jazz trumpeter Don Cherry, it offered exceptionally dense but not really jazzy music."[19] Fellow Rolling Stone contributor Will Hermes deemed The Bells to be among Reed's less memorable albums but highlighted the title track as a "nine-minute spiritual-jazz elegy for a man standing on a ledge, which at the time Reed surely was."[23]

Reed's opinion

Reed showed a fondness for the album in later times; in a 1996 Mojo interview, when asked by Barney Hoskyns what his most underrated album, Reed replied: "The Bells. I really like that album. I think it sold two copies, and probably both to me."[24] Similarly, in a 2004 Uncut interview, when asked by Jon Wilde which of his albums "are ripe for critical rehabilitation", Reed singled out The Bells for being "one of my favourites. I think that's a great-sounding album. The older I get, the more meaningful it becomes to me. Whether, as you say, it's ripe for reappraisal, is another matter. No one liked it when it came out and nobody seems to have changed their mind about it since. I love it, though."[25]

Track listing

All tracks are written by Lou Reed, with additional writers noted.

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Stupid Man" | Nils Lofgren | 2:33 |

| 2. | "Disco Mystic" |

| 4:30 |

| 3. | "I Want to Boogie with You" | Fonfara | 3:55 |

| 4. | "With You" | Lofgren | 2:21 |

| 5. | "Looking for Love" | 3:29 | |

| 6. | "City Lights" | Lofgren | 3:22 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7. | "All Through the Night" | Don Cherry | 5:00 |

| 8. | "Families" | Boles | 6:09 |

| 9. | "The Bells" | Fogel | 9:17 |

| Total length: | 40:37 | ||

Personnel

Credits are adapted from The Bells liner notes.[26]

Musicians

- Lou Reed – lead and backing vocals, electric guitar, guitar synthesizer, bass synthesizer (track 8), horn arrangement (tracks: 1-3, 5-9), producer

- Ellard "Moose" Boles – 12-string electric guitar (track 8), bass guitar, bass synthesizer, backing vocals

- Michael Fonfara – piano, Fender Rhodes, synthesizer, backing vocals, executive producer

- Don Cherry – African hunting guitar, trumpet, horn arrangement (track 4)

- Marty Fogel – ocarina, soprano and tenor saxophone, Fender Rhodes (track 9), horn arrangement

- Michael Suchorsky – percussion

Production and artwork

- René Tinner – engineer

- Manfred Schunke – mixing

- Ted Jensen – mastering

- Donn Davenport – art direction, design

- Howard Fritzson – art direction, design

- Garry Gross – photography

Charts

| Chart (1979) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australia (Kent Music Report)[27] | 58 |

| New Zealand Albums (RMNZ)[28] | 13 |

| Swedish Albums (Sverigetopplistan)[29] | 44 |

| US Billboard 200[30] | 130 |

References

- ↑ "The Great Rock Discography". p. 681.

- ↑ "The Great Rock Discography". p. 681.

- ↑ "Nils Lofgren: Rock's Most Valuable Player". 3 June 2021.

- ↑ https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/nils-lofgren-new-album-lou-reed-blue-with-lou-802325/%7Caccess-date=November 5, 2022

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Levy, Aidan (April 25, 2019). "Rock & Roll & Free Jazz". Jazz Times. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- ↑ DiMartino, Dave (September 1980). "Lou Reed Tilts The Machine". Creem. Rock's Backpages. Retrieved March 20, 2021 – via Yahoo!. Alt URL

- 1 2 Penman, Ian (February 16, 1996). "Lou Reed: Life After the Leather Jacket". The Guardian.

- 1 2 3 4 Bangs, Lester (June 14, 1979). "The Bells". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Deming, Mark. "The Bells Review by Mark Deming". AllMusic. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- 1 2 3 DeCurtis, Anthony (2017). "Chapter 13: The Bells". Lou Reed: A Life. Boston, Massachusetts: Little Brown & Co. ISBN 978-0316552424. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Savage, Jon (May 5, 1979). "Lou Reed: The Bells (Arista)". Melody Maker.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Murray, Charles Shaar (28 April 1979). "Lou Reed: The Bells (Arista)". NME. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- 1 2 Snowden, Don (January 24, 1979). "Lou Reed: The Bells". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- 1 2 Christgau, Robert (December 31, 1979). "Christgau's Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- 1 2 Deming, Mark. "The Bells - Lou Reed | Songs, Reviews, Credits | AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- 1 2 Kot, Greg (January 12, 1992). "Lou Reed's Recordings: 25 Years Of Path-breaking Music". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- ↑ Larkin, Colin (1997). "Lou Reed". The Virgin Encyclopedia of Popular Music. London: Virgin Books. p. 1,003. ISBN 1-85227 745 9.

- 1 2 Strong, Martin C. (2006). "Lou Reed". The Great Rock Discography. Edinburgh: Canongate Books. p. 909. ISBN 1-84195-827-1.

- 1 2 Hull, Tom. "[The New] Rolling Stone Album Guide: Lou Reed [New Version]". Tom Hull. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- 1 2 Morrison, Dave (November 1992). "Reviews: Reissues". Select: 95. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ↑ Edroso, Roy (1999). "Lou Reed". In Buckley, Jonathan; Duane, Orla; Ellingham, Mark; Spicer, Al (eds.). The Rough Guide to Rock (2nd ed.). London: Rough Guides. pp. 813–814. ISBN 1-85828-457-0.

- ↑ Hull, Tom. "[The New] Rolling Stone Album Guide: Lou Reed [Old Version]". Tom Hull. Retrieved April 2, 2023.

- ↑ Hermes, Will (October 27, 2013). "Lou Reed's Essential Albums". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved April 3, 2023.

- ↑ Hoskyns, Barney (March 1996). "A Dark Prince at Twilight: Lou Reed". Mojo.

- ↑ Wilde, Jon (May 2004). "Lou Reed: The Uncut Questionnaire". Rock's Backpages. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ↑ The Bells (CD booklet). Lou Reed. Arista Records. 1979.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ↑ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 249. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ↑ "Charts.nz – Lou Reed – The Bells". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ↑ "Swedishcharts.com – Lou Reed – The Bells". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ↑ "Lou Reed Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved March 20, 2021.