The role of the sea in culture has been important for centuries, as people experience the sea in contradictory ways: as powerful but serene, beautiful but dangerous.[2] Human responses to the sea can be found in artforms including literature, art, poetry, film, theatre, and classical music. The earliest art representing boats is 40,000 years old. Since then, artists in different countries and cultures have depicted the sea. Symbolically, the sea has been perceived as a hostile environment populated by fantastic creatures: the Leviathan of the Bible, Isonade in Japanese mythology, and the kraken of late Norse mythology. In the works of the psychiatrist Carl Jung, the sea symbolises the personal and the collective unconscious in dream interpretation.

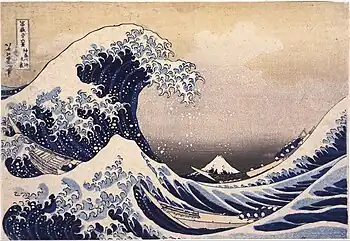

The sea and ships have been depicted in art ranging from simple drawings on the walls of huts in Lamu to seascapes by Joseph Turner and Dutch Golden Age painting. The Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai created colour prints of the moods of the sea, including The Great Wave off Kanagawa. The sea has appeared in literature since Homer's Odyssey (8th century BC). The sea is a recurring theme in the Haiku poems of the Japanese Edo period poet Matsuo Bashō (松尾 芭蕉) (1644–1694).

The sea plays a major role in Homer's epic poem the Odyssey, describing the ten-year voyage of the Greek hero Odysseus who struggles to return home across the sea, encountering sea monsters along the way. In the Middle Ages, the sea appears in romances such as the Tristan legend, with motifs such as mythical islands and self-propelled ships. Pilgrimage is a common theme in stories and poems such as The Book of Margery Kempe. From the Early Modern period, the Atlantic slave trade and penal transportation used the sea to transport people against their will from one continent to another, often permanently, creating strong cultural resonances, while burial at sea has been practised in various ways since the ancient civilisations of Egypt, Greece, and Rome.

Contemporary sea-inspired novels have been written by Joseph Conrad, Herman Wouk, and Herman Melville; poems about the sea have been written by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Rudyard Kipling and John Masefield. The sea has inspired much music over the centuries including sea shanties, Richard Wagner's The Flying Dutchman, Claude Debussy's La mer (1903–1905), Charles Villiers Stanford's Songs of the Sea (1904) and Songs of the Fleet (1910), Edward Elgar's Sea Pictures (1899) and Ralph Vaughan Williams' A Sea Symphony (1903–1909).

Humans and the sea

Human reactions to the sea are found in, for example, literature, art, poetry, film, theatre, and classical music, as well as in mythology and the psychotherapeutic interpretation of dreams. The importance of the sea to maritime nations is shown by the intrusions it makes into their culture; its inclusion in myth and legend; its mention in proverbs and folk song; the use of ships in votive offerings; the importance of ships and the sea in initiation ceremonies and in mortuary rites; children playing with toy boats; adults making model ships; crowds gathering at the launch of a new ship; people congregating at the arrival or departure of a vessel and the general attitude towards maritime matters.[3] Trade and exchange of ideas with neighbouring nations is one of the means by which civilizations advance and evolve.[4] This happened widely among the ancient peoples living in lands bordering the Mediterranean Sea, as well as in India, China and other Southeast Asian nations.[5] The World Oceans Day takes place every 8 June.[6]

Early history

Petroglyphs depicting boats made of papyrus are among rock art dating back 40,000 years on the shores of the Caspian Sea.[7] James Hornell studied traditional, indigenous watercraft and considered the significance of the "oculi" or eyes painted on the prows of boats which may have represented the watchful gaze of a god or goddess protecting the vessel.[8] The Vikings portrayed fierce heads with open jaws and bulging eyes at bow and stern of their longships to ward off evil spirits,[9] and the figureheads on the prows of sailing ships were regarded with affection by mariners and represented the belief that the vessel needed to find its way. The Egyptians placed figures of holy birds on the prow while the Phoenicians used horses representing speed. The Ancient Greeks used boars' heads to symbolise acute vision and ferocity while Roman boats often mounted a carving of a centurion representing valour in battle. In northern Europe, serpents, bulls, dolphins and dragons were customary used to decorate ships' prows and by the thirteenth century, the swan was commonly used to signify grace and mobility.[10]

Symbolism, myth and legend

Symbolically, the sea has long been perceived as a hostile and dangerous environment populated by fantastic creatures: the gigantic Leviathan of the Bible,[12] the shark-like Isonade in Japanese mythology,[13][14] and the ship-swallowing Kraken of late Norse mythology.[15]

The Greek mythology of the sea includes a complex pantheon of gods and other supernatural creatures. The god of the sea, Poseidon, is accompanied by his wife, Amphitrite, who is one of the fifty Nereids, sea nymphs whose parents were Nereus and Doris.[16] The Tritons, sons of Poseidon, who were variously represented with the tails of fish or seahorses, formed Poseidon's retinue along with the Nereids.[17] The mythic sea was further peopled by dangerous sea monsters such as Scylla.[18] Poseidon himself had something of the shifting character of the sea, presiding not only over the sea, but also earthquakes, storms and horses. Neptune occupied a similar position in Roman mythology.[19] Another Greek sea-god, Proteus, specifically embodies the domain of sea change, the adjectival form "protean" meaning mutable, able to assume many forms. Shakespeare makes use of this in Henry VI, Part 3, where Richard III boasts "I can add colors to the chameleon, Change shapes with Proteus for advantages".[20]

In Southeast Asia, the importance of the sea gave rise to many myths of epic ocean voyages, princesses on distant islands, monsters and magical fish lurking in the deep.[5] In Northern Europe, kings were sometimes given ship burials when the body was laid in a vessel surrounded by treasure and costly cargo and set adrift on the sea.[21] In North America, various creation stories have a duck or other creature dive to the bottom of the sea and bring up some mud out of which the dry land was formed.[22] Atargatis was a Syrian deity known as the mermaid-goddess and Sedna was the goddess of the sea and marine animals in Inuit mythology.[23] In Norse mythology Ægir was the sea god and Rán, his wife, was the sea goddess while Njörðr was the god of sea travel.[24] It was best to propitiate the gods before setting out on a voyage.[25]

In the works of the psychiatrist Carl Jung, the sea symbolizes the personal and the collective unconscious in dream interpretation:[26]

[Dream] By the sea shore. The sea breaks into the land, flooding everything. Then the dreamer is sitting on a lonely island.[Interpretation] The sea is the symbol of the Collective unconscious, because unfathomed depths lie concealed beneath its reflecting surface.

[Footnote] The sea is a favourite place for the birth of visions (i.e. invasions by unconscious contents).[26]

In art

The sea and ships have been depicted in art ranging from simple drawings of dhows on the walls of huts in Lamu[3] to seascapes by Joseph Turner. The genre of marine art became especially important in the paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, with works showing the Dutch navy at the peak of its military prowess.[27] Artists such as Jan Porcellis, Simon de Vlieger, Jan van de Cappelle, Hendrick Dubbels, Willem van de Velde the Elder and his son, Ludolf Bakhuizen and Reinier Nooms created maritime paintings in a wide variety of styles.[27] The Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai created colour prints of the moods of the sea, including The Great Wave off Kanagawa showing the destructive force of the sea at the same time as its ever-changing beauty.[1] The 19th century Romantic artist Ivan Aivazovsky created some 6,000 paintings, the majority of which depict the sea.[28][29]

In literature and film

Ancient

The sea has appeared in literature since at least the time of the Ancient Greek poet Homer who describes it as the "wine dark sea" (oînops póntos).[lower-alpha 1] In his epic poem the Odyssey, written in the 8th century BC,[33] he describes the ten-year voyage of the Greek hero Odysseus who struggles to return home across the sea after the war with Troy described in the Iliad. His wandering voyage takes him from one strange and dangerous land to another, experiencing among other maritime hazards shipwreck, the sea-monster Scylla, the whirlpool Charybdis and the island Ogygia of the nymph Calypso.[34]

The soldier Xenophon, in his Anabasis, told how he witnessed the roaming 10,000 Greeks, lost in enemy territory, seeing the Black Sea from Mount Theches, after participating in Cyrus the Younger's failed march against the Persian Empire in 401 BC.[35] The 10,000 joyfully shouted "Thálatta! Thálatta! "(Greek: Θάλαττα! θάλαττα!) — "The Sea! The Sea!"[30] The famous[30] shout has come to symbolise victory, national freedom, triumph over hardship, and more romantically the "longing for a return to the primal sea."[36]

The sea is a recurring theme in the Haiku poems of the leading Japanese Edo period poet Matsuo Bashō (松尾 芭蕉) (1644–1694).[37]

Ptolemy, writing in his Geographia in about 150 AD, described how the Atlantic Ocean and Indian Ocean were great enclosed seas and believed that a vessel venturing into the Atlantic would soon reach the countries of the East. His map of the then known world was remarkably accurate but from the fourth century onwards, civilisation suffered a setback at the hands of barbarian invaders and knowledge of geography took a backward step. In the seventh century, Isidore of Seville produced a "wheel map" in which Asia, Africa and Europe were arranged like segments in an orange, separated by the "Mare Mediterranean", "Nilus" and "Tanais" and surrounded by "Oceanus". It was not until the fifteenth century that Ptolemy's maps were used again and Henry the Navigator of Portugal initiated ocean exploration and maritime research. Encouraged by him, Portuguese navigators explored, mapped and charted the west coast of Africa and the Eastern Atlantic and this knowledge prepared the way for the great voyages of exploration that were to follow.[38]

Medieval

Medieval literature offers rich encounters with the sea, as in the well-known romance of Tristan and The Voyage of Saint Brendan. The sea acts as an arbiter of good and evil and the barrier of fate, as in the mercantilist fifteenth-century poem The Libelle of Englyshe Polycye. Medieval romances frequently ascribe a prominent role to the sea. The originally Mediterranean family of Apollonius of Tyre romances use the Odyssean format of the extended sea voyage. The story may have influenced Guillaume Roi d'Angleterre and Chaucer’s The Man of Law's Tale. Other romances, such as the Romance of Horn, the Conte del Graal of Chrétien de Troyes, Partonopeu de Blois or the Tristan legend employ the sea as a structural feature and source of motifs: setting adrift, mythical islands, and self-propelled ships. Some of these maritime motifs appear in the lais of Marie de France.[39][40][41] Many religious works written in the Middle Ages reflect on the sea. The ascetic sea desert (heremum in oceano) appears in Adomnán’s Life of Columba or The Voyage of Saint Brendan, an entirely seaborne tale cognate with the Irish immram or maritime pilgrimage tale.[lower-alpha 2] The Old English poem The Seafarer has a similar background. Sermons sometimes speak of the sea of the world and the ship of the Church, and moralistic interpretations of shipwreck and floods. These motifs in chronicles such as the Chronica majora of Matthew Paris, and Adam of Bremen’s History of the Archbishops of Hamburg-Bremen. Similar motives are treated in Biblical paraphrases, e.g. the anonymous Middle English poem Patience, and pilgrimage narratives and poems such as The Book of Margery Kempe, Saewulf's Voyage, The Pilgrims' Sea Voyage. Marian devotion created prayers to Mary as the Star of the Sea (stella maris), both as lyrics and as features in larger works like John Gower's Vox Clamantis.[39][40]

Early modern

William Shakespeare makes frequent and complex use of mentions of the sea and things associated with it.[42] The following, from Ariel's Song in Act I, Scene ii of The Tempest, is felt to be "wonderfully evocative", indicating a "profound transformation":[43]

Full fathom five thy father lies:

Of his bones are coral made:

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Other early modern authors to have made use of the cultural associations of the sea include John Milton in his poem Lycidas (1637), Andrew Marvell in his Bermudas (1650) and Edmund Waller in his The Battle of the Summer Islands (1645). The scholar Steven Mentz argues that "the oceans .. figure the boundaries of human transgression; they function symbolically as places in the world into which mortal bodies cannot safely go".[44] In Mentz's view, the European exploration of the oceans in the fifteenth century caused a shift in the meanings of the sea. Whereas a garden symbolised happy coexistence with nature, life was threatened at sea: the ocean counterbalanced the purely pastoral.[44]

Modern

In modern times, the novelist Joseph Conrad wrote several sea-inspired books including Lord Jim and The Nigger of the 'Narcissus' which drew on his experience as a captain in the merchant navy.[45] The American novelist Herman Wouk writes that "Nobody, but nobody, could write about storms at sea like Conrad".[46] One of Wouk's own marine novels, The Caine Mutiny (1952), won the Pulitzer Prize.[47] Herman Melville's 1851 novel Moby-Dick was described by the poet John Masefield as speaking "the whole secret of the sea".[48]

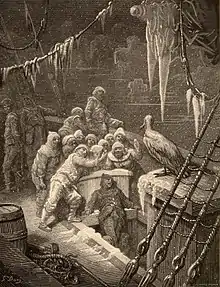

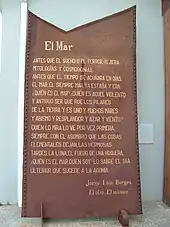

A large seabird, the albatross, played a central part in Samuel Taylor Coleridge's influential 1798 poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which in turn gave rise to the usage of albatross as metaphor for a burden.[49] In his 1902 poem The Sea and the Hills, Rudyard Kipling expresses the urge for the sea, and uses alliteration[50] to suggest the sea's sound and rhythms:[51] "Who hath desired the Sea?—the sight of salt water unbounded— The heave and the halt and the hurl and the crash of the comber wind-hounded?"[52] John Masefield also felt the pull of the sea in his Sea Fever, writing "I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky."[53] The Argentine Jorge Luis Borges wrote the 1964 poem El mar (The Sea), treating it as something that constantly regenerates the world and the people who contemplate it, and that is very close to the essence of being human.[54]

Numerous books and films have taken war at sea as their subject, often dealing with real or fictionalised incidents in the Second World War. Nicholas Monsarrat's 1951 novel The Cruel Sea follows the lives of a group of Royal Navy sailors fighting the Battle of the Atlantic during World War II;[55] it was made into a 1952 film of the same name.[56] The novelist Herman Wouk, reviewing "five best nautical yarns", writes that "The Cruel Sea was a major best seller and became a hit movie starring Jack Hawkins. Its authenticity is unmistakable ... His description of a torpedoed crew, terrified, clinging to life rafts in the blackest of nights, is, indeed, too authoritative for comfort—we soon feel ourselves in that sea."[46] Anthony Asquith used a dramatised documentary style in his 1943 film We Dive at Dawn, while Noël Coward and David Lean's 1942 In Which We Serve combined information with drama. Pat Jackson's 1944 Western Approaches was, unusually for the time, shot in Technicolor, at sea in rough weather and sometimes actually in battle. Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's 1956 The Battle of the River Plate tells a tale of "gentlemanly gallantry"[57] of the scuttling of the Admiral Graf Spee. A very different message, of "duplicitous diplomacy [and] flawed intelligence"[57] is the theme of Richard Fleischer, Toshio Masuda and Kinji Fukasaku's $22 million epic Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970). Depicting an earlier era of naval warfare in the age of sail, Peter Weir's 2003 Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World, based on Patrick O'Brian's series of Aubrey-Maturin novels.[57]

Submarine films like Robert Wise's 1958 Run Silent, Run Deep[57] constitute a distinctive subgenre of the war film, depicting the stress of submarine warfare. The genre makes distinctive use of the soundtrack, which attempts to bring home the emotional and dramatic nature of conflict under the sea. For example, in the 1981 Das Boot, the sound design works together with the hours-long film format to depict lengthy pursuit with depth charges and the many times repeated ping of sonar, as well as the threatening sounds of a destroyer's propeller and of an approaching torpedo.[58]

In music

A sailor's work was hard in the days of sail. When off duty, many sailors played musical instruments or joined in unison to sing folksongs such as the mid-eighteenth century ballad The Mermaid, a song which expressed the sailors' superstition that seeing a mermaid foretold a shipwreck.[59] When on duty, there were many repetitive tasks, such as turning the capstan to raise the anchor and heaving on ropes to raise and lower the sails. To synchronise the crew's efforts, sea shanties were sung, with a lead singer performing the verse and the sailors joining in the chorus.[60] In the Royal Navy in Nelson's time, these work songs were banned, being replaced by the notes of a fife or fiddle, or the recitation of numbers.[61]

The sea has inspired much music over the centuries. In Oman, Fanun Al Bahr (Sea Music) is played by an ensemble with kaser, rahmani and msindo drums, s'hal cymbals, tassa tin drums, and mismar bagpipes; the piece called Galfat Shobani plays through the work of renewing the caulking of a wooden ship.[62] Richard Wagner stated that his 1843 opera The Flying Dutchman[63] was inspired by a memorable sea crossing from Riga to London, his ship being delayed in the Norwegian fjords at Tvedestrand for two weeks by storms.[64] The French composer Claude Debussy's 1903–1905 work La mer (The Sea), completed at Eastbourne on the English Channel coast, evokes the sea with "a multitude of water figurations".[65] Other works composed at about this time include Charles Villiers Stanford's Songs of the Sea (1904) and Songs of the Fleet (1910), Edward Elgar's Sea Pictures (1899) and Ralph Vaughan Williams' choral work, A Sea Symphony (1903–1909).[66] The English composer Frank Bridge wrote an orchestral suite called The Sea in 1911, also completed at Eastbourne.[67] Four Sea Interludes (1945) is an orchestral suite by Benjamin Britten that forms part of his opera Peter Grimes.[68]

Human cargo

.jpg.webp)

Humans have gone to sea also for the specific purpose of transporting other humans. This has included for penal transportation, such as from Britain to Australia;[69] the slave trade, including the post-1600 Atlantic slave trade from Africa to the Americas;[70] and the ancient practice of burial at sea.[71]

Penal transportation

From around 1600 until the American War of Independence, convicts sentenced to "transportation", often for minor crimes, were carried to America; after that, such convicts were taken to New South Wales, in what is now Australia.[72][73] Some 20% of modern Australians are descended from transported convicts.[74] The convict era has inspired novels, films, and other cultural works, and it has significantly shaped Australia's national character.[75]

Atlantic slave trade

In the Atlantic slave trade, enslaved people, mostly from central and western Africa and usually sold by West Africans to European slave traders, were carried across the sea, mainly to the Americas. The slave trade regularly used the triangular trade route from Europe (with manufactured goods) to West Africa and on to the Americas (with slaves), and then back to Europe (with goods such as sugar).[76] The South Atlantic and Caribbean economies depended on a secure supply of labour for agriculture and manufacturing of goods to sell in Europe, and in turn the European economy depended in large part on the profits from the trade.[77] Some 12 million Africans arrived in the Americas, and many more died on the journey, powerfully influencing the culture of the Americas.[78][79]

Burial at sea

The burial of entire or cremated bodies at sea has been practised by countries around the world since ancient times, with instances recorded from the ancient civilisations in Egypt, Greece, and Rome.[71] Practices vary by country and by religion; for example, the United States allows human remains to be buried at sea at least 3 nautical miles from land, and if the remains are uncremated the water must be at least 600 feet deep,[81] while in Islam burial by lowering a weighted clay vessel into the sea is permitted when a person dies on a ship.[82]

Footnotes

- ↑ Since the sea is not usually wine-red, this has been taken as a poetic formula, but the classicist R. Rutherfurd-Dyer reports that he saw a sea under a volcanic ash cloud that was indeed red: "The ash cloud formed an unusually vivid sunset, reflected in the outgoing tide of the dark estuary. The rich blackish red and oily texture of the water were almost identical to Mavrodaphni. I realized I was looking at precisely that sea at which Homer's Achilles looks idon epi oinopa ponton (II. 23.143)."[32]

- ↑ Three of these have survived: The Voyage of Mael Duin, The Voyage of Snedgus and MacRiagla, and The Voyage of the Húi Corra (Immram curaig Máele Dúin, Immram Snédgus ocus Maic Riagla, and Immram curaig Ua Corra).

References

- 1 2 Stow, p. 8

- ↑ Stow, p. 10

- 1 2 Westerdahl, Christer (1994). "Maritime cultures and ship types: brief comments on the significance of maritime archaeology". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. 23 (4): 265–270. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.1994.tb00471.x.

- ↑ Diamond, Jared (2005). Collapse. Penguin. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-14-027951-1.

- 1 2 Cotterell, pp. 206–208

- ↑ "World Oceans Day: Why June 8 is an important day for our planet". USA Today. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ↑ "Gobustan Rock Art Cultural Landscape". World Heritage Centres. UNESCO. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ↑ Prins, A. H. J. (1970). "Maritime art in an Islamic context: oculos and therion in Lamu ships". The Mariner's Mirror. 56 (3): 327–339. doi:10.1080/00253359.1970.10658550.

- ↑ "Ship's figurehead". Explore. British Museum. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ↑ "Ship's figureheads". Research. Royal Naval Museum Library. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- ↑ Ehon Hyaku Monogatari (Tōsanjin Yawa). Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ↑ The Bible (King James Version). 1611. pp. Job 41: 1–34.

- ↑ "Isonade 磯撫 (いそなで)" (in English and Japanese). Obakemono.com. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ Shunsen, Takehara (1841). Ehon Hyaku Monogatari (絵本百物語, "Picture Book of a Hundred Stories") (in Japanese). Kyoto: Ryûsuiken.

- ↑ Pontoppidan, Erich (1839). The Naturalist's Library, Volume 8: The Kraken. W. H. Lizars. pp. 327–336. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ↑ "Nereides". Theoi. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ "Tritones". Theoi. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ Kerenyi, C. (1974). The Gods of the Greeks. Thames and Hudson. pp. 37–40. ISBN 0-500-27048-1.

- ↑ Cotterell, p. 54

- ↑ Shakespeare, William. Henry VI, Part Three, Act III, Scene ii. 1591.

- ↑ Cotterell, p. 127

- ↑ Cotterell, p. 272

- ↑ Cotterell, pp. 132–134

- ↑ Lindow, John (2008). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. pp. 241–243. ISBN 978-0-19-515382-8.

- ↑ Cotterell, pp. 7–9

- 1 2 Jung, Carl Gustav (1985). Dreams. Translated by Hull, R.F.C. Ark Paperbacks. pp. 122, 192. ISBN 978-0-7448-0032-6.

- 1 2 3 Slive, Seymour (1995). Dutch Painting, 1600–1800. Yale University Press. pp. 213–216. ISBN 0-300-07451-4.

- ↑ Rogachevsky, Alexander. "Ivan Aivazovsky (1817–1900)". Tufts University. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014.

- ↑ "Aivazovsky's View of Venice leads Russian art auction at $1.6m". Paul Fraser Collectibles. 29 November 2012. Archived from the original on 19 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 Xenophon (translation by Dakyns, H. G.) (1897). "Anabasis". Book 4, Chapter 7. Gutenberg.org. Retrieved 26 April 2013.

But as the shout became louder and nearer, and those who from time to time came up, began racing at the top of their speed towards the shouters, and the shouting continually recommenced with yet greater volume as the numbers increased, Xenophon settled in his mind that something extraordinary must have happened, so he mounted his horse, and taking with him Lycius and the cavalry, he galloped to the rescue. Presently they could hear the soldiers shouting and passing on the joyful word, "The sea! the sea!"

- ↑ Hutchinson, Walter (1914–1915). Hutchinson's History of the Nations. Hutchinson.

- ↑ Annas, George J. (1989). "At Law: Who's Afraid of the Human Genome?". The Hastings Center Report. 19 (4): 19–21. doi:10.2307/3562296. JSTOR 3562296.

- ↑ Homer (translation by Rieu, D. C. H.) (2003). The Odyssey. Penguin. pp. xi. ISBN 0-14-044911-6.

- ↑ Porter, John (8 May 2006). "Plot Outline for Homer's Odyssey". University of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ↑ Xenophon. Anabasis ("An Ascent", or "Going Up").

- ↑ Xenophon; Rood, Tim (2009). The Expedition of Cyrus. Oxford University Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-19-955598-7.

- ↑ Basho, Matsuo. "A Selection of Matsuo Basho's Haiku". Greenleaf. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ↑ Russell, S. F.; Yonge, C. M. (1963). The Seas: Our Knowledge of Life in the Sea and How it is Gained. Frederick Warne. pp. 6–8. ASIN B0007ILSQ0.

- 1 2 Sobecki, Sebastian (2005). "The Sea," in International Encyclopaedia for the Middle Ages

- 1 2 Sobecki, Sebastian (2008). The Sea and Medieval English Literature ISBN 978-1-84615-591-8

- ↑ Sobecki, Sebastian (2011). The Sea and Englishness in the Middle Ages: Maritime Narratives, Identity & Culture ISBN 9781843842767

- ↑ Poole, William (2001). Holland, Peter (ed.). "Shakespeare and Religions". Shakespeare Survey. Cambridge University Press. 54: 201–212.

- ↑ "Sea Change". World Wide Words. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- 1 2 Mentz, Steven (2009). "Toward a Blue Cultural Studies: The Sea, Maritime Culture, and Early Modern English Literature" (PDF). Literature Compass. 6 (5): 997–1013. doi:10.1111/j.1741-4113.2009.00655.x.

- ↑ Najder, Zdzisław (2007). Joseph Conrad: A Life. Camden House. p. 187.

- 1 2 Wouk, Herman (30 November 2012). "Herman Wouk on nautical yarns". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ↑ "The Caine Mutiny". Pulitzer Prize First Edition Guide. 2006. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ Van Doren, Carl (1921). "Chapter 3. Romances of Adventure. Section 2. Herman Melville". The American Novel. Bartleby.com. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ Lasky, E (1992). "A modern day albatross: The Valdez and some of life's other spills". The English Journal. 81 (3): 44–46. doi:10.2307/820195. JSTOR 820195.

- ↑ "Alliteration's Artful Aid". The Argus. Melbourne, Victoria. 7 November 1903. p. 6. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ↑ Hamer, Mary (2007). "The Sea and the Hills". The Kipling Society. Retrieved 2 July 2013.

- ↑ Kipling, Rudyard (1925). A Choice of Songs. Methuen. p. 56.

- ↑ Masefield, John (1902). "Sea Fever". Salt-water Balads. Retrieved 14 July 2013.

- ↑ Fernandez, Camilo. "Apuntes Sobre la Poetica de Jorge Luis Borges y Lectura del Poema 'El Mar'". Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ↑ Monsarrat, Nicholas (1951). The Cruel Sea. Cassell.

- ↑ "Cruel Sea, The (1952)". British Film Institute. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Parkinson, David (28 October 2014). "10 great battleship and war-at-sea films". British Film Institute. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ Koldau, Linda Maria (2010). "Sound effects as a genre-defining factor in submarine films". MedieKultur. 26 (48): 18–30. doi:10.7146/mediekultur.v26i48.2117.

- ↑ Nelson-Burns, Lesley. "The Mermaid". Folk Music of England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales & America. Child ballads: 289. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ Nelson-Burns, Lesley. "Sea shanties". The Contemplator's Microencyclopedia of Folk Music. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ "Life at sea in the age of sail". National Maritime Museum. 1 February 2000. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ "Galfat Shobani - Sea music from Oman". Qatar Digital Library / British Library. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ↑ Wagner, Richard (1844). "Der fliegende Holländer, WWV 63". IMSLP Petrucci Music Library. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ↑ Wagner, Richard (1843). "An Autobiographical Sketch". The Wagner Library. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ↑ Potter, Caroline (1994). "Debussy and Nature". In Trezise, Simon (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Debussy. Cambridge Companions to Music. Cambridge University Press. p. 149. ISBN 0-521-65478-5.

- ↑ Schwartz, Elliot S. (1964). The Symphonies of Ralph Vaughan Williams. University of Massachusetts Press. ASIN B0007DESPS.

- ↑ Bridge, Frank (1920). "The Sea, H. 100". IMSLP Petrucci Music Library. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ↑ "Benjamin Britten: Peter Grimes: Four Sea Interludes (1945)". Boosey & Hawkes. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- ↑ "Criminal transportation". The National Archives. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ↑ Klein, Herbert S.; Vinson III, Ben (2007). African Slavery in Latin America and the Caribbean (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195189421.

- 1 2 "History of Death / Water Burials". AETN UK (History channel). Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ Ekirch, A. Roger (1987). Bound for America. The transportation of British convicts to the colonies, 1718–1775. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820092-7.

- ↑ "Why were convicts transported to Australia?". Sydney Living Museums. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ↑ "Online records highlight Australia's convict past". ABC News. 25 July 2007.

- ↑ Hirst, John (July 2008). "An Oddity From the Start: Convicts and National Character". The Monthly (July 2008).

- ↑ "The capture and sale of slaves". Liverpool: International Slavery Museum. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ↑ Mannix, Daniel (1962). Black Cargoes. Viking Press. pp. Introduction–1–5.

- ↑ Segal, Ronald (1995). The Black Diaspora: Five Centuries of the Black Experience Outside Africa. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 4. ISBN 0-374-11396-3.

- ↑ Eltis, David; Richardson, David (2002). Northrup, David (ed.). The Numbers Game (2nd ed.). Houghton Mifflin. p. 95.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Anon; artwork by Joseph Mallord William Turner (February 2010). "Peace – Burial at Sea". Tate Etc. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Burials at Sea". U. S. Environmental Protection Agency. 5 October 2010. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ "Rules About Burial of the Dead Body". Ahlul Bayt Digital Islamic Library Project. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

General sources

The following books are useful on many aspects of the topic.

- Cotterell, Arthur, ed. (2000). World Mythology. Parragon. ISBN 978-0-7525-3037-6.

- Mack, John (2011). The Sea: A Cultural History. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-809-8.

- Raban, Jonathan (1992). The Oxford Book of the Sea. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-214197-2.

- Stow, Dorrik (2004). Encyclopedia of the Oceans. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860687-7.