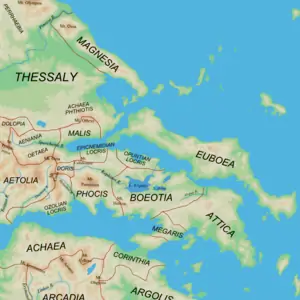

The Thessalian League (Thessalian Aeolic: Κοινὸν τοῦν Πετθαλοῦν, Koinòn toûn Petthaloûn; Attic: Κοινὸν τῶν Θετταλῶν, Koinòn tôn Thettalôn; Ionic and Koine Greek: Κοινὸν τῶν Θεσσαλῶν, Koinòn tôn Thessalôn) was a koinon or loose confederacy of feudal-like poleis and tribes in ancient Thessaly, located in the Thessalian plain in Greece. The seat of the Thessalian League was Larissa.

Organization and Civil War

The history of the Thessalian League can be traced back to the rule of king Aleuas, a member of the Aleuadae clan. One source states that it was under Aleuas that Thessaly was divided into four regions. Some time after the death of Aleuas, it is believed that the Aleuadae split into two families, the Aleuadae and the Scopadae. The former were based in the city of Larissa, which later became the capital of the League. The two families formed two powerful aristocratic parties and bore considerable influence over Thessaly.[1]

Jason and Macedon

A lack of records makes it difficult to have any details of Thessalian life or politics until the 5th century BCE, when records discuss the rise of another Thessalian family—the dynasts of Pherae. The dynasts of Pherae gradually rose to hold great power and influence over the Thessalians, challenging the power of the Aleuadae.[1] By 374 BCE, the Pherae and the Aleuadae were united with the common, agricultural population of Thessaly by Jason of Pherae. Jason's military organization and work to unify the state challenged the Macedonian influence over Thessaly. Macedonia had left a legacy of pitting Thessalian cities against one another to prevent the rise of a powerful national state. To this end, King Archelaus of Macedonia had seized border provinces of Thessaly for substantial periods and taken sons of Thessalian aristocrats as hostages. However, according to one source, “Jason’s army was said to number eight thousand cavalry and twenty thousand hoplite mercenaries, a force large enough to encourage Philip’s father to seek a nonaggression pact with him.”[2]

The late fourth and early third centuries witnessed uneasy peace, which were punctuated by the emergence of civil war.

While Sparta established dominance elsewhere in Greece, Jason strengthened the Thessalian League and made alliances with Macedon and the Boeotian League (374 BCE). His leadership gave the League unity and power.[3] In 370 BCE, while Thessaly was still preoccupied with the Macedonian intervention, Jason was assassinated and replaced by his nephew Alexander II, who displayed outrageous tyrannical behavior.[4] As a result, the traditional aristocratic families from different cities formed a military alliance against Alexander II of Pherae. Once a united state, Thessaly fell into political instability following these developments. With a lack of leadership among the Thessalians, noble families took control in the 5th century BCE in an attempt to put an end to central authority. However, the internal conflict divided Thessaly into two sides: the western inland area of Thessalian League and the eastern coastal towns of Pherae controlled by the tyrants.[5]

One historian spoke of this period as follows, “Thessaly remained politically fragmented and hence unstable, and the chaos of civil war in the region attracted the interest of a series of outsiders: Boeotia, Athens, and eventually Philip II of Macedonia.”[2] In the year 364 BCE, the new joint Thessalo-Boeotian army, led by the Theban general Pelopidas, marched to Alexander II of Pherae to intervene in the civil war. When the military result was not finalized, Pelopidas was summoned to enter the protracted struggle between Alexander II and Ptolemy Aloros in Macedonia- the Theban general, however, urged rearrangement of the Thessalian League at that time. The most important parts of the rearrangement were the replacement of the tagos by an archon, and the reorganization of the Thessalian army according to the four tetrads of Aleuas. Pelopidas’ death during the battle assured continuous regional civil war. In the late summer of 358 BCE, Alexander II of Pherae's death opened a path for Philip’s diplomatic conquest of Thessaly at the request of Cineas of Larissa. The civil war in Thessaly lasted for six years until Philip’s intervention put an end to it.

War

The League and Philip of Macedon

In 355 BCE, Thebes convinced several members of the Amphictyonic League to declare war on Phocis, a fellow member of the League. Thessaly voted with Thebes, but when the Phocian general Philomelus defeated 6,000 troops fielded by the Thessalians, Thessaly divided into opposing regions. The tyrants of Pherae allied with Athens to support Phocis while the Thessalian League remained opposed to Phocis and sought the aid of Philip of Macedon. Philip was attracted by the military potential of the Thessalian League. Thessaly was famous for its horse-breeding as well as the skill and effectiveness of its cavalry, considered equal to Philip's own Macedonian Companions.[5] When Philip answered the call for help and captured the port of Pherae, he became fully engaged on the Theban side of the Third Sacred War. His interventions eventually resulted in the defeat of the tyrants of Pherae around 353 BCE and he was elected president (archon) of the Thessalian League. Being entrusted with this position for life, Philip was able to unite the resources and manpower of both Macedonia and Thessaly in order to create a powerful alliance that gave him tremendous influence over the Greek city-states.[6] At his death, many Greek cities rejoiced and some rose up to expel, or attempt to expel, their Macedonian garrisons. This revolt resulted in an invasion of the plain of Peneus by Alexander. Faced with the Macedonian army suddenly appearing behind them, and having had little time to organize any resistance, the League surrendered and elected Alexander archon in his father’s place.[7]

The League and Rome

On the eve of the Second Macedonian War, Thessaly was divided between the two dominant powers of Aitolia and Macedonia. When the Roman commander Titus Quinctius Flamininus’s legions set foot on mainland Greece in 199 BCE, he and Aitolian allies defeated the Thessalians under Philip V of Macedon at the battle at Cynoscephalae by 197 BCE, bringing a systematic change of the political boundaries of central Greece. His victory proved the superiority of the legion over the phalanx and Roman influence and control spread throughout Thessaly.

At the end of Second Macedonian War in 196 BCE, Rome established Thessaly as a koinon, Federal League, and cultivated its development to make it part of hegemonic powers of central and northern Greece.[8] At the ceremony of the Isthmian Games in 196 BCE, Flamininus, associated in name with the Roman Senate, published a decree that declared: “The Senate of Rome and Titus Quinctius the pro-consul having overcome King Philip and the Macedonians, leave the following peoples free, without garrisons and subject to no tribute and governed by their countries’ laws—the Corinthians, Phocians, Locrians, Euboeans, Phthiotic Achaeans, Magnesians, Thessalians, and Perrhaibians”.[8] Hence, Thessalian Leagues started administering their affairs with a judicious condition of order for the first time in 150 or more years of chaos and turmoil. Flamininus started to act as a central political figure of Thessaly and took initiatives to restore the local governments, through establishing a new census and restricting high classes’ possibility to hold magistrates and council positions, that led to a stable federal league of Thessaly. Under Roman control, the Thessalian League gradually increased in size and power as a loyal ally and it played a significant role in the campaigning and theatre of operation during the Roman civil wars.[8] During the Third Macedonian War about 300 Thessalian cavalry fought alongside Rome.[9] The Thessalian League was one of the several Greek leagues the Roman tolerated until 146 BCE, when the Roman commander Mummius razed the city of Corinth to the ground, disbanded the leagues, and informally reduced Greece to provincial status.[10]

See also

References

- 1 2 Smith, William (1849). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. pp. 108–109.

- 1 2 Gabriel, R.A. (2010). Philip II of Macedonia: Greater Than Alexander. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books. pp. 13, 199.

- ↑ Botsford, George (1956). Hellenic History (4th ed.). United States of America: New York: The MacMillan Company. p. 273.

- ↑ Lewis, Sian (2006). Ancient Tyranny. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 136.

- 1 2 Ashley, James (2004). The Macedonian Empire: the Era of Warfare under Philip II and Alexander the Great, 359-323 B.C. McFarland & Company. pp. 130–132.

- ↑ Hammond, N. G. L. (1994). Philip of Macedon. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 45–52. ISBN 0801849276. OCLC 29703810.

- ↑ Bury, J.D. (1937). A History of Greece. New York: Modern Library. p. 725.

- 1 2 3 Graninger, Denver (2011). Cult and Koinon in Hellenistic Thessaly. United States of America: Leiden:Brill. pp. 7, 28, 40.

- ↑ Head, Duncan. Armies of the Macedonian and Punic Wars 359 BC to 146 BC. p. 100. ISBN 9780904417265.

- ↑ Botsford, George; Robinson (1956). Hellenic History (4th ed.). United States of America: New York: McMillan. pp. 452–454.

External links

![]() Media related to Ancient Thessaly at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ancient Thessaly at Wikimedia Commons