Sir Thomas Fleming | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger | |

| Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench | |

| In office 1607–1613 | |

| Monarch | James I |

| Preceded by | Sir John Popham |

| Succeeded by | Sir Edward Coke |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 1544 Newport, Isle of Wight, England |

| Died | 7 August 1613 Stoneham Park, Hampshire, England |

| Resting place | St Nicolas' Church, North Stoneham, England |

| Spouse | Mary James |

| Children | 7 sons, 7 daughters |

| Parent(s) | John Fleming, Dorothy Harris |

| Education | Godshill School and Lincoln's Inn |

| Known for | Judge, Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, Chief Baron of the Exchequer |

Sir Thomas Fleming (April 1544 – 7 August 1613) was an English judge and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1581 and 1611. He was judge in the trial of Guy Fawkes following the Gunpowder Plot.[1] He held several important offices, including Lord Chief Justice, Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer and Solicitor General for England and Wales.

Early life

Fleming was the son of John Fleming, a general trader and mercer of Newport on the Isle of Wight, and his wife Dorothy Harris. The family lived in a house just to the east of the entrance to the corn market from the High Street in Newport.[2] The Fleming family line had strong historical connections to the Isle of Wight, with several mentions of the name cropping up in previous historical documents and books.[2] He went to school in Godshill[2] and studied law at Lincoln's Inn where he was called to the bar in 1574.[3]

Career

In 1581, Fleming was elected Member of Parliament for Kingston upon Hull after the existing members were dismissed as idle and impotent. He was elected MP for Winchester in 1584, and was re-elected in 1593.[4] His progression within the legal profession was fast (possibly due to several personal connections with the monarch); he became a serjeant-at-law in 1594, and shortly afterwards became Recorder of London.[2]

Solicitor General

In 1595, on the personal intervention of Elizabeth I, Fleming (in preference to Francis Bacon) was promoted to the position of Solicitor General, succeeding Sir Edward Coke who had become Attorney General.[2] Historians regard the Queen's decision as a pointed reminder to her courtiers, most of whom had lobbied hard for Bacon, that she had the ultimate power of patronage.[5] Fleming was praised by his contemporaries, more particularly Coke, for his "great judgments, integrity and discretion".[6]

In 1597, Fleming was elected MP for Hampshire. He purchased the North Stoneham estate in 1599[7] from the young Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton who inherited the title and estate at the age of eight.[8] He was elected MP for Southampton in 1601,[4] but his maiden speech on 20 November of that year was a disaster and Fleming broke down; he never addressed the House of Commons again.[2] When James I became King in 1603, Fleming was reappointed Solicitor General and was knighted on 23 July 1603.[3] He was re-elected MP for Southampton for another term in 1604.[2]

Lord Chief Baron

He was elevated to the bench as Lord Chief Baron of the Exchequer in 1604.[2] It was in this capacity that he tried Guy Fawkes, having been one of the members of parliament at the time of the Gunpowder Plot. His conduct during the trial was criticised as he was accused of attempting "to look wise, and say nothing".[2]

Another notable case during his tenure as Chief Baron was Bates's Case, also called The Case of Impositions, of 1606, on the power of the Crown to levy taxes without Parliamentary approval. John Bates, a merchant trading with Turkey, had refused to pay the unpopular tax on the import of currants. Fleming, in giving judgement for the Crown, held in effect that the King had an unlimited power to levy taxes in any way he thought fit: the power of the King is both ordinary and absolute... absolute power, existing for the nation's safety, varies with the royal wisdom. The judgement was controversial and was even said to have contributed to the tensions between Charles I and Parliament in the next reign. Fleming, a merchant's son, also displayed a somewhat cynical attitude to the business community, dismissing appeals to the common good with the scathing remark that the end of every private merchant is not the common good but his particular profit.[9]

Lord Chief Justice

In 1607, on the death of Sir John Popham, Fleming was elevated to the post of Lord Chief Justice of England.[2] The following year he obtained a Charter for Incorporation for Newport from the King, providing for the election of a Mayor instead of the historical appointed Bailiff.[2] He assisted in the establishment of a free grammar school in the town.[2] Also in 1608, Fleming was one of the judges at the trial of the post nati in 1608, siding with the majority of the judges in declaring that persons born in Scotland after the accession of James I were entitled to the privileges of natural-born subjects in England.[6] The convocation of Oxford University granted him the award of MA on 7 August 1613, which was the day he died.[3]

Death

Fleming died suddenly on 7 August 1613 at Stoneham Park in Hampshire, having given to his servants and farm labourers what was known in Hampshire as a "hearing day."[2] After joining in the festivities, he went to bed, apparently in sound health, but was taken suddenly ill, and died before morning.[2] He was buried in St. Nicolas' Church, North Stoneham, where a stately monument[10][11] records the numerous successes of his career.[2] Known locally as the "Floating Flemings",[12] it is ornamented with recumbent whole length figures of Fleming in his robes, with his official insignia, and his wife, with ruff and hood, and the singular waist favoured by ladies of the Tudor era.[2] Underneath is the following inscription:

In most Assvred Hope of A Blessed Resvrection, Here Lyeth Interred ye Bodie of Sir Thomas Flemyng, Knight, Lord Chief Jvstice of England; Great Was His Learning, Many Were His Virtves. He Always Feared God & God Still Blessed Him & ye Love & Favour Both of God & Man Was Daylie Upon Him. He Was in Especiall Grace & Favour With 2 Most Worthie & Virtvovs Princes Q. Elizabeth & King James. Many Offices and Dygnities Were Conferred Upon Him. He Was First Sargeant at Law, Then Recorder of London; Then Solicitor Generall to Both ye Said Princes. Then Lo: Chief Baron of ye Exchequer & after Lo: Chief Jvstice of England. All Which Places He Did Execvte With So Great Integrity, Justice & Discretion that Hys Lyfe Was Of All Good Men Desired, His Death Of All Lamented. He Was Borne at Newporte In ye Isle Of Wight, Brough Up In Learning & ye Studie Of ye Lawe. In ye 26 Yeare Of His Age He Was coopled in ye Blessed State of Matrimony To His Virtvovs Wife, ye La: Mary Fleming, With whom He Lived & Continewed In that Blessed Estate By ye Space Of 43 Yeares. Having By Her In that Tyme 15 Children, 8 Sonnes & 7 Davghters, Of Whom 2 Sonnes & 5 Davghters Died In His Life Time. And Afterwards In Ripeness of Age and Fulness of Happie yeares yt Is to Saie ye 7th Day of Avgvst 1613 in ye 69 Yeare Of His Age, He Left This Life For a Better, Leaving Also Behind Him Livinge Together With His Virtvovs Wife 6 Soones & 2 Davghters.[2]

Family

Fleming married on 13 February 1570 to his cousin, Mary James, the daughter of Dr Mark James, who was a personal physician of Queen Elizabeth I.[2] They were married at St Thomas' Church, Newport, and lived at Carisbrooke Priory, the lease of which he purchased from the Secretary of State, Francis Walsingham.[2] They had fifteen children of whom six sons and two daughters survived after Fleming's death. His sons Thomas and Philip were both members of parliament. His son Francis was Master of the Horse to Oliver Cromwell. Other sons were Walter, John, James and William. His daughters were Elizabeth, Mary, Jane, Eleanor, Dowsabell, Mary and another of name unknown. There was another child of name and gender unknown. Elizabeth married Robert Meverel and their daughter, also Elizabeth, married Thomas Cromwell, 1st Earl of Ardglass.

Fleming's descendants were still in possession of the Stoneham Park estate in 1908.[8] The Fleming Arms public house and Fleming Road, both in Swaythling, are named after the family. There is another public house of the same name in Binstead, Isle of Wight.

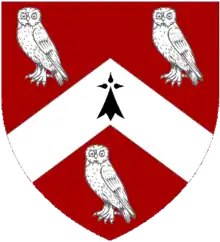

Arms

|

|

References

- ↑ "Sir Thomas Fleming (1544–1613)". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Adams, William Henry Davenport (1862). Nelsons' hand-book to the Isle of Wight. Oxford University. pp. 181–183. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- 1 2 3 'Alumni Oxonienses, 1500–1714: Faber-Flood', Alumni Oxonienses 1500–1714: Abannan-Kyte (1891), pp. 480–509. Date accessed: 13 December 2011

- 1 2 "History of Parliament". History of Parliament Trust. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ↑ Sir J. E. Neale Elizabeth I Pelican Books reissue pp.340–1

- 1 2 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Fleming, Sir Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 495.

- ↑ "The 'Fleming Estate' in Hampshire & the Isle of Wight". Willis Fleming Historical Trust. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- 1 2 Page, William (1908). A History of the County of Hampshire: Volume 3. pp. 478–481.

- ↑ State Trials, Volume 2

- ↑ "Monument to Thomas Fleming and his wife". Art & Architecture. The Courtauld Institute of Art. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ↑ "Monument to Thomas Fleming and his wife". Art & Architecture. The Courtauld Institute of Art. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ↑ Mann, John Edgar (2002). Book of the Stonehams. Tiverton: Halsgrove. p. 43. ISBN 1-84114-213-1.

- ↑ The visitation of London in the year 1568. : Taken by Robert Cooke, Clarenceux king of arms, and since augmented both with descents and arms. The Harleian Society. 1869.