.jpg.webp)

J. R. R. Tolkien's maps, depicting his fictional Middle-earth and other places in his legendarium, helped him with plot development, guided the reader through his often complex stories, and contributed to the impression of depth and worldbuilding in his writings.

Tolkien stated that he began with maps and developed his plots from them, but that he also wanted his maps to be picturesque. Later fantasy writers also often include maps in their novels.

The publisher Allen & Unwin commissioned Pauline Baynes to paint a map of Middle-earth, based on Tolkien's draft maps and his annotations; it became iconic. A later redrafting of the maps by the publisher HarperCollins however made the maps look blandly professional, losing the hand-drawn feeling of Tolkien's maps.

Maps

The Hobbit

The Hobbit contains two simple maps and only around 50 placenames. In the view of the Tolkien critic Tom Shippey, the maps are largely decorative in the "Here be tygers" tradition, adding nothing to the story.[2] The first is Thror's map, in the fiction handed down to Thorin, showing little but the Lonely Mountain drawn in outline with ridgelines and entrances, and parts of two rivers, decorated with a spider and its web, English labels and arrows, and two texts written in runes.[T 1] The other is a drawing of "Wilderland", from Rivendell in the west to the Lonely Mountain and Smaug the dragon in the east. The Misty Mountains are drawn in three dimensions. Mirkwood is shown as a mixture of closely packed tree symbols, spiders and their webs, hills, lakes, and villages. The map is overprinted with placenames in red.[T 2] Both maps have a heavy vertical line not far from the left-hand side, the one on the map of Wilderland marked "Edge of the Wild". This line represented the printed delineation of the margin of the school paper, which came with the printed instruction "Do not write in this margin".[3]

The Lord of the Rings

The Lord of the Rings contains three maps and over 600 placenames. The maps are a large drawing of the north-west part of Middle-earth, showing mountains as if seen in three dimensions, and coasts with multiple waterlines;[T 3] a more detailed drawing of "A Part of the Shire";[T 4] and a contour map by Christopher Tolkien of parts of Rohan, Gondor, and Mordor, very different in style.[3][T 5] Tolkien worked for many years on the book, using a hand-drawn map of the whole of the north-west of Middle-earth on squared (not graph) paper, each 2cm square representing 100 miles. The map had many annotations in pencil and a range of different inks added over the years, the older ones faded until almost illegible. The paper became soft, torn and yellowed through intensive use, and a fold down the centre had to be mended using parcel tape.[6] He made a detailed pencil, ink and coloured pencil design on graph paper, enlarged five times in length from the main map of Middle-earth. His son Christopher drew the contour map from the design. The finished map faithfully reproduced the contours, features and labels of his father's design, but omitted the route (with dates) taken by the Hobbits Frodo and Sam on their way to destroy the One Ring in Mount Doom. Father and son worked desperately to finish the map in time for publication:[5]

I had to devote many days, the last three virtually without food or bed, to drawing re-scaling and adjusting a large map, at which [Christopher] then worked for 24 hours (6am to 6am without bed) in re-drawing just in time.[7]

Shippey notes that many of the places mapped are never used in the text.[2] The map of the Shire is the only one to include political boundaries, in the shape of the divisions between the administrative districts or Farthings.[3]

The Silmarillion

The first edition of The Silmarillion contains two maps. There is a large fold-out drawing of Beleriand.[T 6] The Ered Luin mountain range on its right-hand edge approximately matches the mountain range of that name on the left-hand edge of the main map in The Lord of the Rings. The other is a smaller-scale drawing of the central region of the same area, with coasts, mountains, and rivers but without forests, overprinted in red with the names of the leaders of the Elves in each part of Beleriand.[T 7]

The other continents and regions described in The Silmarillion are not mapped in the book, but Tolkien drew sketches of Arda in its early stages including of Valinor (Aman), and a map of the star-shaped island of Numenor, with little detail other than coasts (with waterlining) and mountains, which was eventually printed in Unfinished Tales.[T 8] Some other absences may be significant; Christopher Tolkien wrote that the frequently mentioned Dwarf-road over the mountains bordering Beleriand is not shown, because the Noldorin Elves who lived there never crossed the mountains.[3]

Functions

Aesthetic experience

The style of Tolkien's maps mixes illustrative principles and purpose with cartographical practice. Alice Campbell, in The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, writes that while they have what Tolkien called an "archaic air", they are not authentically medieval in style.[8] In particular, he allows for blank spaces between features, an 18th-century innovation that meant that the features that were drawn were reliable.[8] Campbell states that Tolkien's mapping style echoes William Morris's Arts and Crafts: "they are functional, but with an eye to grace and beauty", and in her view lie somewhere between illustration and cartography.[8]

Tolkien indeed wrote that "there should be picturesque maps, providing more than a mere index to what is said in the text".[T 9] His maps thus have at least three functions: to help the author construct a consistent plot; to guide the reader; and through the "picturesque", the aesthetic experience, to lead the reader into the imagined secondary world.[9]

From map to plot

In 1954, Tolkien wrote in a letter to the novelist Naomi Mitchison that[T 10]

I wisely started with a map, and made the story fit (generally with meticulous care for distances). The other way about lands one in confusions and impossibilities, and in any case it is weary work to compose a map from a story — as I fear you have found.[T 10]

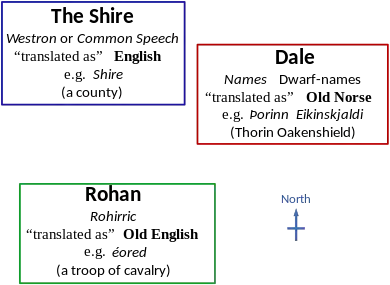

Tolkien developed not only maps but names and languages before he arrived at a plot.[11] He had already used Old Norse for the Dwarves of Dale (to the east) in The Hobbit, and he was using modern English for the Hobbits of the Shire (in the west); his choice of Old English for the riders of Rohan implied a linguistic map of Middle-earth, with different peoples, languages and regions.[12]

Karen Wynn Fonstad, author of The Atlas of Middle-earth,[13] commented that in such a world, writing has to be based on detailed knowledge of each of many types of details; she found herself, as Tolkien had, unable to proceed with the atlas until she had mastered all of them. Distances travelled, the chronology of the quest, geology, and terrain all needed to be understood to create the work.[14]

Impression of depth

Campbell stated that the "lovingly detailed" maps helped to shape the stories and create a "believable whole".[8] In Shippey's view, "the names and the maps give Middle-earth that air of solidity and extent both in space and time which its successors [in 20th century fantasy] so conspicuously lack".[15] One way that this works, he argues, is that readers, far from analysing the etymology of place-names as Tolkien habitually did, take them as labels, "as things .. in a very close one-to-one relationship with whatever they label".[16] That in turn makes maps "extraordinarily useful to fantasy, weighing it down as they do with repeated implicit assurances of the existence of the things they label, and of course of their nature and history too."[16]

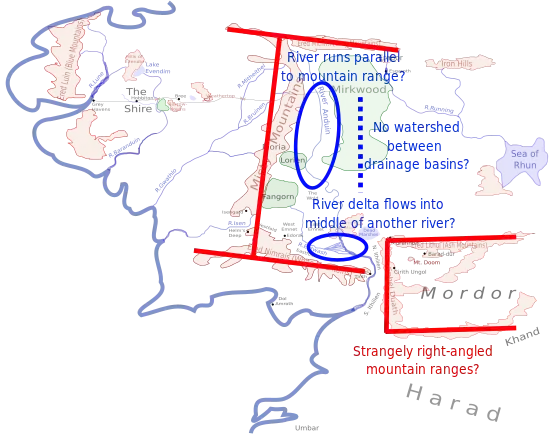

Geomorphological issues

The geologist Alex Acks, writing on Tor.com, outlines the mismatch between Tolkien's maps and the geomorphological processes of plate tectonics which shape the Earth's continents and mountain ranges. Mountains form mainly next to subduction zones where oceanic crust slides under continental crust, or where continents collide and crumple. Stretching of continental crust, by upwelling of magma, creates broken horst and graben landforms. Acks comments that none of these create right-angle junctions in mountain ranges, such as are seen around Mordor and at both ends of the Misty Mountains on Tolkien's maps. Isolated volcanoes far inland, like Mount Doom, are possible but unlikely: most such volcanoes are islands and occur in roughly straight-line groups as the crust moves across a hotspot in Earth's mantle.[17]

Acks identifies a further issue, with Tolkien's rivers. The Earth's major rivers each drain a raised area of land, forming a drainage basin; the river in the basin takes water and sediment down to the sea, or looked at the other way, branches regularly into smaller and smaller streams that lead up into the hills. A river like the Anduin, on the other hand, has very few branches: it runs more or less as a single large stream for hundreds of miles, and parallel to the Misty Mountain range, rather than directly downhill and away from it. Worse, one of its few tributaries, the Entwash, branches out into a river delta, a basically flat place where a river ends, usually by the sea; but the Anduin goes on flowing past this spot, downhill. Acks excuses another oddity, namely that the Anduin cuts through a gap (between the White Mountains of Gondor and the Ephel Duath of Mordor); this is unusual but can happen, as when the Colorado River cuts across the mountainous Basin and Range Province: the river was there before the mountains, and cut its way down through the rock faster than the mountains grew upwards. Acks comments that the inland Sea of Rhûn seems to be in the bottom of a drainage basin. Again, this can happen; but there must be a watershed, high ground separating it from neighbouring drainage basins, in particular that of the Anduin. But the rivers of Mirkwood run eastwards towards the Sea of Rhûn, propelled by an invisible slope from invisible Mirkwood hills.[18]

Fantasy maps before and after Tolkien

Antecedents

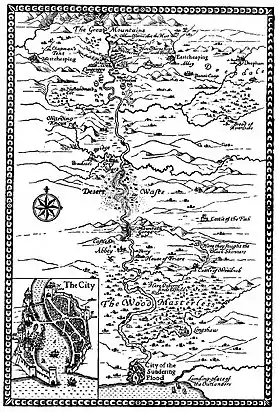

The frontispiece to William Morris's 1897 The Sundering Flood was a map showing the city on a great river, "The Wood Masterless", a "Desert Waste", and towns with English names like "Westcheaping" and "Eastcheaping".[19] The map appears to have been the first fantasy map in the modern sense, defining a wholly invented world.[20] Tolkien stated that he wished to imitate the style and content of Morris's romances,[21] and that he made use of elements from them.[22][23] Other published examples Tolkien may have had in mind while creating his maps include those of Jonathan Swift, who included maps in his 1726 Gulliver's Travels, and those of Robert Louis Stevenson in his 1883 adventure story Treasure Island.[9]

First modern-style fantasy map: the Frontispiece map in William Morris's 1897 The Sundering Flood [20]

First modern-style fantasy map: the Frontispiece map in William Morris's 1897 The Sundering Flood [20]

Influence

Tolkien's maps set a completely new standard for fantasy novels, so that their use has become expected in the genre, which he largely created.[9] Peter Jackson chose to use Tolkien's Middle-earth map in his Lord of the Rings film trilogy.[24][9] Among later bestselling fantasy authors, George R. R. Martin has used maps in all his A Song of Ice and Fire books, starting with A Game of Thrones.[9]

Derived maps

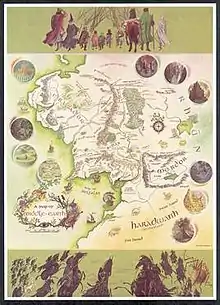

Iconic poster map

In 1969, Tolkien's publisher Allen & Unwin commissioned the illustrator Pauline Baynes to paint a map of Middle-earth. Tolkien supplied her with copies of his draft maps for The Lord of the Rings, and annotated her copy of his son Christopher's 1954 map for The Fellowship of the Ring. Allen & Unwin published Baynes's map as a poster in 1970. It was decorated with a header and footer showing some of Tolkien's characters, and vignettes of some of his stories' locations. The poster map became "iconic" of Middle-earth. She was the only illustrator of whom Tolkien approved.[25][26][27][28]

Redraftings

Campbell writes that the redrafting of the maps by the publishers HarperCollins for a later edition of The Lord of the Rings made the cartography "bland, modern, professional illustration".[1] In her view, this is "an unintentional reversion to decorative but technically inaccurate medieval-style maps",[1] something that she finds misguided, as in his maps "Tolkien desired accuracy more than decoration".[1] In addition, the redrafting loses what she calls "the illusion of Bilbo's own fair copies of older maps and which suggested a culture without printing presses or engraving", through Tolkien's own "charming hand lettering".[1]

Fan cartography

The Tolkien universe has been subject to significant cartographic efforts by fans, some of whom have published their works in print. These include Karen Wynn Fonstad's The Atlas of Middle-earth.[29]

References

Primary

- ↑ Tolkien 1937, at start

- ↑ Tolkien 1937, at end

- ↑ Tolkien 1954, foldout map in first edition

- ↑ Tolkien 1954, map before first chapter

- ↑ Tolkien 1955, foldout map in first edition

- ↑ Tolkien 1977, fold-out map inside back cover

- ↑ Tolkien 1977, map in chapter 14, "Of Beleriand and its Realms"

- ↑ Tolkien 1980, start of part 2 "The Second Age"

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, letter 141 to Allen & Unwin, 9 October 1953

- 1 2 3 Carpenter 1981, letter 144 to Naomi Mitchison, 25 April 1954

Secondary

- 1 2 3 4 5 Campbell 2013, p. 408.

- 1 2 Shippey 2005, p. 114.

- 1 2 3 4 Campbell 2013, p. 407.

- ↑ McIlwaine 2018, pp. 394–395.

- 1 2 McIlwaine 2018, pp. 394–397.

- ↑ McIlwaine 2018, pp. 400–401.

- ↑ McIlwaine 2018, p. 394.

- 1 2 3 4 Campbell 2013, p. 405.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sundmark 2017, pp. 221–238.

- ↑ Shippey 2005, pp. 131–133.

- ↑ Shippey 2005, p. 133.

- ↑ Shippey 2005, pp. 126–133.

- ↑ Fonstad 1991, p. 1.

- ↑ Fonstad 2006, pp. 133–136.

- ↑ Shippey 2005, p. 118.

- 1 2 Shippey 2005, p. 115.

- 1 2 Acks 2017a.

- 1 2 Acks 2017b.

- ↑ Morris 1897, frontispiece.

- 1 2 Smee 2007, pp. 75–82.

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, #1

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, #226

- ↑ Tolkien 1937, p. 183, note 10

- ↑ Walker 1981, article 9.

- 1 2 McIlwaine 2018, p. 384.

- 1 2 Kennedy 2016.

- 1 2 Bodleian 2016.

- ↑ Scull & Hammond 2017, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Danielson, Stentor (21 July 2018). "Re-reading the Map of Middle-earth: Fan Cartography's Engagement with Tolkien's Legendarium". Journal of Tolkien Research. 6 (1). Article 4. ISSN 2471-934X.

Sources

- Acks, Alex (1 August 2017a). "Tolkien's Map and The Messed Up Mountains of Middle-earth". Tor.com. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- Acks, Alex (10 October 2017b). "Tolkien's Map and the Perplexing River Systems of Middle-earth". Tor.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- Bodleian (13 June 2016). "Rare map of Middle-earth goes on display at the Bodleian Libraries". Bodleian Library. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- Campbell, Alice (2013) [2007]. "Maps". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 405–408. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-31555-2.

- Fonstad, Karen Wynn (1991). The Atlas of Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-618-12699-6.

- Fonstad, Karen Wynn (2006). "Writing 'TO' the Map". Tolkien Studies. 3 (1): 133–136. doi:10.1353/tks.2006.0018. S2CID 170599010.

- Kennedy, Maev (3 May 2016). "Tolkien annotated map of Middle-earth acquired by Bodleian Library". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- McIlwaine, Catherine (2018). Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth. Bodleian Library. p. 384. ISBN 978-1851244850.

- Morris, William (1897). The Sundering Flood. Kelmscott Press. p. frontispiece.

- Scull, Christina; Hammond, Wayne G. (2017). The J. R. R. Tolkien Companion and Guide. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-0082-1454-8.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-2611-0275-0.

- Smee, Lilla Julia (2007). Inventing Fantasy: The Prose Romances of William Morris (PDF). University of Sydney (PhD thesis).

- Sundmark, Björn (2017). "Mapping Middle Earth: A Tolkienian Legacy". In Goga, Nina; Kümmerling-Meibauer, Bettina (eds.). Maps and Mapping in Children's Literature: Landscapes, seascapes and cityscapes. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 221–238. ISBN 978-90-272-6546-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1937). Douglas A. Anderson (ed.). The Annotated Hobbit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 2002). ISBN 978-0-618-13470-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954). The Two Towers. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 1042159111.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Unfinished Tales. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-29917-3.

- Walker, R. C. (1981). "The Cartography of Fantasy". Mythlore. 7 (4). article 9.

External links

- Insights into Mapping the Imagined World of J.R.R. Tolkien by Sabine Timpf, Professor of Geoinformatics, Augsburg University