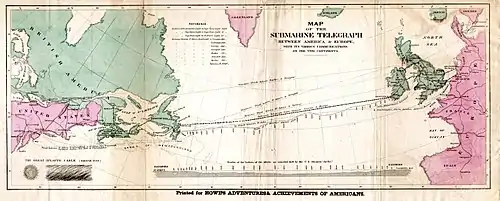

Transatlantic telegraph cables were undersea cables running under the Atlantic Ocean for telegraph communications. Telegraphy is now an obsolete form of communication, and the cables have long since been decommissioned, but telephone and data are still carried on other transatlantic telecommunications cables. The first cable was laid in the 1850s from Valentia Island off the west coast of Ireland to Bay of Bulls, Trinity Bay, Newfoundland. The first communications occurred on August 16th 1858, but the line speed was poor, and efforts to improve it caused the cable to fail after three weeks.

The Atlantic Telegraph Company led by Cyrus West Field constructed the first transatlantic telegraph cable.[1] The project began in 1854 and was completed in 1858. The cable functioned for only three weeks, but was the first such project to yield practical results. The first official telegram to pass between two continents was a letter of congratulations from Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom to President of the United States James Buchanan on 16 August. Signal quality declined rapidly, slowing transmission to an almost unusable speed. The cable was destroyed the following month when Wildman Whitehouse applied excessive voltage to it while trying to achieve faster operation. It has been argued that the cable's faulty manufacture, storage and handling would have caused its premature failure in any case.[2] Its short life undermined public and investor confidence and delayed efforts to restore a connection.

The second cable was laid in 1865 with much improved material. It was laid from the ship SS Great Eastern, built by John Scott Russell and Isambard Kingdom Brunel and skippered by Sir James Anderson. More than halfway across, the cable broke, and after many rescue attempts, it was abandoned.[3] In July 1866 a third cable was laid from The Anglo-American Cable house on the Telegraph Field, Foilhommerum. On July 13th, Great Eastern steamed westward to Heart's Content, Newfoundland, and on July 27th the successful connection was put into service. The 1865 cable was also retrieved and spliced, so two cables were in service.[4] These cables proved more durable. Line speed was very good, and the slogan "Two weeks to two minutes" was coined to emphasize the great improvement over ship-borne dispatches. The cable altered for all time personal, commercial and political relations between people across the Atlantic. Since 1866, there has been a permanent cable connection between the continents.

In the 1870s, duplex and quadruplex transmission and receiving systems were set up that could relay multiple messages over the cable.[5] Before the first transatlantic cable, communications between Europe and the Americas took place only by ship and could be delayed for weeks by severe winter storms. By contrast, the transatlantic cable allowed a message and a response in the same day.

Early history

In the 1840s and 1850s several people proposed or advocated construction of a telegraph cable across the Atlantic, including Edward Thornton and Alonzo Jackman.[6]

As early as 1840 Samuel F. B. Morse proclaimed his faith in the idea of a submarine line across the Atlantic Ocean. By 1850 a cable was run between England and France. That year, Bishop John T. Mullock, head of the Catholic Church in Newfoundland, proposed a telegraph line through the forest from St. John's to Cape Ray and cables across the Gulf of St. Lawrence from Cape Ray to Nova Scotia across the Cabot Strait.

Around the same time, a similar plan occurred to Frederic Newton Gisborne, a telegraph engineer in Nova Scotia. In the spring of 1851 he procured a grant from the Newfoundland legislature and, having formed a company, began building the landline.

A plan takes shape

In 1854, businessman and financier Cyrus West Field invited Gisborne to his house to discuss the project. From his visitor, Field considered the idea that the cable to Newfoundland might be extended across the Atlantic Ocean.

Field was ignorant of submarine cables and the deep sea. He consulted Morse and Lieutenant Matthew Maury, an authority on oceanography. The charts Maury constructed from soundings in the logs of multiple ships indicated that there was a feasible route across the Atlantic. It seemed so ideal for cable laying that Maury named it Telegraph Plateau. Maury's charts also indicated that a route directly to the US was too rugged to be tenable and considerably longer.[7] Field adopted Gisborne's scheme as a preliminary step to the bigger undertaking and promoted the New York, Newfoundland and London Telegraph Company to establish a telegraph line between America and Europe.

The first step was to finish the line between St. John's and Nova Scotia, which was undertaken by Gisborne and Field's brother, Matthew.[8] In 1855 an attempt was made to lay a cable across the Cabot Strait in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. It was laid out from a barque in tow of a steamer. When half the cable was laid, a gale rose, and the line was cut to keep the barque from sinking. In 1856 a steamboat was fitted out for the purpose, and the link from Cape Ray, Newfoundland to Aspy Bay, Nova Scotia was successfully laid.[9] The project's final cost exceeded $1 million, and the transatlantic segment would cost much more.[10]

In 1855, Field crossed the Atlantic, the first of 56 crossings in the course of the project,[11] to consult with John Watkins Brett, the greatest authority on submarine cables at the time. Brett's Submarine Telegraph Company laid the first ocean cable in 1850 across the English Channel, and his English and Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company had laid a cable to Ireland in 1853, the deepest cable to that date.[12] Further reasons for the trip were that all the commercial manufacturers of submarine cable were in Britain,[8] and Field had failed to raise significant funds for the project in New York.[10]

Field pushed the project ahead with tremendous energy and speed. Even before forming a company to carry it out, he ordered 2,500 nautical miles (4,600 km; 2,900 mi)[13] of cable from the Gutta Percha Company.[10] The Atlantic Telegraph Company was formed in October 1856, with Brett as president and Field as vice president. Charles Tilston Bright, who already worked for Brett, was made chief engineer, and Wildman Whitehouse, a medical doctor self-educated in electrical engineering, was appointed chief electrician. Field provided a quarter of the capital himself.[14] After the remaining shares were sold, largely to existing investors in Brett's company,[15] an unpaid board of directors was formed, which included William Thomson (the future Lord Kelvin), a respected scientist. Thomson also acted as a scientific advisor.[10] Morse, a shareholder in the Nova Scotia project and acting as the electrical advisor, was also on the board.[16]

First transatlantic cable

The cable consisted of 7 copper wires, each weighing 26 kg/km (107 pounds per nautical mile), covered with three coats of gutta-percha (as suggested by Jonathan Nash Hearder[17]), weighing 64 kg/km (261 pounds per nautical mile), and wound with tarred hemp, over which a sheath of 18 strands, each of 7 iron wires, was laid in a close helix. It weighed nearly 550 kg/km (1.1 tons per nautical mile), was relatively flexible, and could withstand tension of several tens of kilonewtons (several tons).

The cable from the Gutta Percha Company was armoured separately by wire-rope manufacturers, the standard practice at the time. In the rush to proceed, only four months were allowed for the cable's completion.[18] As no wire-rope maker had the capacity to make so much cable in such a short period, the task was shared by two English firms: Glass, Elliot & Co. of Greenwich and R.S. Newall and Company of Birkenhead.[19] Late in manufacturing, it was discovered that the two batches had been made with strands twisted in opposite directions.[20] This meant that they could not be directly spliced wire-to-wire, as the iron wire on both cables would unwind when it was put under tension during laying.[21] The problem was solved by splicing through an improvised wooden bracket to hold the wires in place,[22] but the mistake created negative publicity for the project.[20]

The British government gave Field a subsidy of £1,400 a year (£140,000 today) and loaned ships for cable laying and support. Field also solicited aid from the U.S. government, and a bill authorizing a subsidy was submitted in Congress. It passed the Senate by only a single vote, due to opposition from protectionist senators. It passed in the House of Representatives despite similar resistance and was signed by President Franklin Pierce.

The first attempt, in 1857, was a failure. The cable-laying vessels were the converted warships HMS Agamemnon and USS Niagara, borrowed from their respective governments. Both were needed as neither could hold 2,500 nautical miles of cable alone.[23] The cable was started at the white strand near Ballycarbery Castle in County Kerry, on the southwest coast of Ireland, on August 5, 1857.[24] It broke on the first day, but was grappled and repaired. It broke again over Telegraph Plateau, nearly 3,200 m (10,500 ft) deep, and the operation was abandoned for the year. Three hundred miles (480 km) of cable were lost, but the remaining 1,800 miles (2,900 km) were sufficient to complete the task. During this period, Morse clashed with Field, was removed from the board, and took no further part in the enterprise.[25]

The problems with breakage were due largely to difficulty controlling the cable tensions with the braking mechanism as the cable was payed out. A new mechanism was designed and successfully tested in the Bay of Biscay with Agamemnon in May 1858.[26] On 10 June, Agamemnon and Niagara set sail to try again. Ten days out they encountered a severe storm, and the enterprise was nearly brought to a premature end. The ships were top-heavy with cable, which could not all fit in the holds, and the ships struggled to stay upright. Ten sailors were hurt, and Thomson's electrical cabin was flooded.[27] The vessels arrived at the middle of the Atlantic on June 25 and spliced cable from the two ships together. Agamemnon payed out eastwards towards Valentia Island, and Niagara westward towards Newfoundland.[21] The cable broke[22] after less than 3 nautical miles (5.6 km; 3.5 mi), again after about 54 nautical miles (100 km; 62 mi), and for a third time when about 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) had been run out of each vessel.

The expedition returned to Queenstown, County Cork, Ireland. Some directors were in favour of abandoning the project and selling off the cable, but Field persuaded them to keep going.[22] The ships set out again on 17 July, and the middle splice was finished on 29 July 1858. The cable ran easily this time. Niagara arrived in Trinity Bay, Newfoundland on 4 August, and the next morning the shore end was landed. Agamemnon arrived at Valentia Island on 5 August; the shore end was landed at Knightstown and laid to the nearby cable house.[28]

First contact

Test messages were sent from Newfoundland beginning 10 August 1858. The first was successfully read at Valentia on 12 August and in Newfoundland on 13 August. Further test and configuration messages followed until 16 August, when the first official message was sent via the cable:

Directors of Atlantic Telegraph Company, Great Britain, to Directors in America:—Europe and America are united by telegraph. Glory to God in the highest; on earth peace, good will towards men.[29][30][31]

Next was the text of a congratulatory telegram from Queen Victoria to President James Buchanan at his summer residence in the Bedford Springs Hotel in Pennsylvania, expressing hope that the cable would prove "an additional link between the nations whose friendship is founded on their common interest and reciprocal esteem". The President responded: "It is a triumph more glorious, because far more useful to mankind, than was ever won by conqueror on the field of battle. May the Atlantic telegraph, under the blessing of Heaven, prove to be a bond of perpetual peace and friendship between the kindred nations, and an instrument destined by Divine Providence to diffuse religion, civilization, liberty, and law throughout the world."[32]

The messages were hard to decipher; Queen Victoria's message of 98 words took 16 hours to send.[29][33] Nonetheless, they engendered an outburst of enthusiasm. The next morning a grand salute of 100 guns resounded in New York City, streets were hung with flags, bells of the churches were rung, and at night the city was illuminated.[34] On 1 September there was a parade, followed by an evening torchlight procession and a fireworks display that caused a fire in the Town Hall.[35] Bright was knighted for his part, the first such honour to the telegraph industry.[36]

Failure of the first cable

Operation of the 1858 cable was plagued by conflict between two of the project's senior members – Thomson and Whitehouse. Whitehouse was a medical doctor by training, but had taken an enthusiastic interest in the new electrical technology and given up his medical practice to follow a new career. He had no formal training in physics; all his knowledge was gained through practical experience. The two clashed even before the project began, when Whitehouse disputed Thomson's law of squares when the latter presented it to a British Association meeting in 1855. Thomson's law predicted that transmission speed on the cable would be very slow due to an effect called retardation.[37] To test the theory, Bright gave Whitehouse overnight access to the Magnetic Telegraph Company's long underground lines.[38] Whitehouse joined several lines together to a distance similar to the transatlantic route and declared that there would be no problem.[39] Morse was also present at this test and supported Whitehouse.[40] Thomson believed that Whitehouse's measurements were flawed and that underground and underwater cables were not fully comparable.[41] Thomson believed that a larger cable was needed to mitigate the retardation problem. In mid-1857, on his own initiative, he examined samples of copper core of allegedly identical specification and found variations in resistance up to a factor of two. But cable manufacture was already underway, and Whitehouse supported use of a thinner cable, so Field went with the cheaper option.[23]

Another point of contention was the itinerary for deployment. Thomson favoured starting mid-Atlantic and the two ships heading in opposite directions, which would halve the time required. Whitehouse wanted both ships to travel together from Ireland so that progress could be reported back to the base in Valentia through the cable.[23] Whitehouse overruled Thomson's suggestion on the 1857 voyage, but Bright convinced the directors to approve a mid-ocean start on the subsequent 1858 voyage.[27] Whitehouse, as chief electrician, was supposed to be on board the cable-laying vessel, but repeatedly found excuses for the 1857 attempt, the trials in the Bay of Biscay,[42] and the two attempts in 1858.[27] In 1857, Thomson was sent in his place,[23] and in 1858 Field diplomatically assigned the two to different ships to avoid conflict—but as Whitehouse continued to evade the voyage, Thomson went alone.[27]

Thomson's mirror galvanometer

.jpg.webp)

After his experience on the 1857 voyage, Thomson realised that a better method of detecting the telegraph signal was required. While waiting for the next voyage, he developed his mirror galvanometer, an extremely sensitive instrument, much better than any until then. He requested £2,000 from the board to build several, but was given only £500 for a prototype and permission to try it on the next voyage.[42] It was extremely good at detecting the positive and negative edges of telegraph pulses that represented a Morse "dash" and "dot" respectively (the standard system on submarine cables—as, unlike overland telegraphy, both pulses were of the same length). Thomson believed that he could use the instrument with the low voltages from regular telegraph equipment even over the vast length of the Atlantic cable. He successfully tested it on 2,700 miles (4,300 km) of cable in underwater storage at Plymouth.[42]

The mirror galvanometer proved yet another point of contention. Whitehouse wanted to work the cable with a very different scheme,[43] driving it with a massive high-voltage induction coil producing several thousand volts, so enough current would be available to drive standard electromechanical printing telegraphs used on inland telegraphs.[44] Thomson's instrument had to be read by eye and was not capable of printing. Nine years later, he invented the syphon recorder for the second transatlantic attempt in 1866.[45] The decision to start mid-Atlantic, combined with Whitehouse dropping out of another voyage, left Thomson on board Agamemnon sailing towards Ireland, with a free hand to use his equipment without Whitehouse's interference. Although Thomson had the status of a mere advisor to engineer C. W. de Sauty, it was not long before all electrical decisions were deferred to him. Whitehouse, staying behind in Valentia, remained out of contact until the ship reached Ireland and landed the cable.[46]

Around this time, the board started having doubts over Whitehouse's generally negative attitude. Not only did he repeatedly clash with Thomson, but was also critical of Field, and his repeated refusals to carry out his primary duty as chief electrician onboard ship made a very bad impression. With the removal of Morse, Whitehouse had lost his only ally on the board,[47] but at this time no action was taken.[42]

Cable is damaged and Whitehouse dismissed

When Agamemnon reached Valentia on 5 August, Thomson handed over to Whitehouse, and the project was declared a success to the press. Thomson received clear signals throughout the voyage using the mirror galvanometer, but Whitehouse immediately connected his own equipment. The effects of the cable's poor handling and design, and Whitehouse's repeated attempts to drive up to 2,000 volts through the cable, compromised the cable's insulation. Whitehouse attempted to hide the poor performance and was vague in his communications. The expected inaugural message from Queen Victoria had been widely publicised, and when it was not forthcoming, the press speculated that there were problems. Whitehouse announced that five or six weeks would be required for "adjustments". The Queen's message had been received in Newfoundland, but Whitehouse was unable to read the confirmation copy sent back the other way. Finally, on 17 August, he announced receipt. What he did not announce was that the message had been received on the mirror galvanometer when he finally gave up trying with his own equipment. Whitehouse had the message reentered into his printing telegraph locally so he could send on the printed tape and pretend that it had been received that way.[48]

In September 1858, after several days of progressive deterioration of the insulation, the cable failed altogether.[49] The reaction to the news was tremendous. Some writers even hinted that the line was a mere hoax; others pronounced it a stock-exchange speculation. Whitehouse was recalled for the board's investigation, and Thomson took over in Valentia, tasked with reconstructing the events that Whitehouse had obfuscated. Whitehouse was held responsible for the failure and dismissed.[50] The cable might have failed eventually anyway, but Whitehouse certainly brought it about much sooner. The cable was particularly vulnerable in the first hundred miles from Ireland, consisting of the old 1857 cable that was spliced into the new lay and known to be poorly manufactured. Samples showed that in places the conductor was badly off-centre and could easily break through the insulation due to mechanical strains during laying. Tests were conducted on samples of cable submerged in seawater. When perfectly insulated, there was no problem applying thousands of volts. However, a sample with a pinprick hole "lit up like a lantern" when tested, and a large hole was burned in the insulation.[51]

Although the cable was never put in service for public use and never worked well, there was time for a few messages to be passed that went beyond testing. The collision between the Cunard Line ships Europa and Arabia was reported on 17 August. The British Government used the cable to countermand an order for two regiments in Canada to embark for England, saving £50,000. A total of 732 messages were passed before the cable failed.[36]

Preparing a new attempt

Field was undaunted by the failure. He was eager to renew the work, but the public had lost confidence in the scheme, and his efforts to revive the company were futile. It was not until 1864 that, with the assistance of Thomas Brassey and John Pender, he succeeded in raising the necessary capital. The Glass, Elliot, and Gutta-Percha Companies were united to form the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company (Telcon, later part of BICC), which undertook to manufacture and lay the new cable. C. F. Varley replaced Whitehouse as chief electrician.[1]

In the meantime, long cables had been submerged in the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. With this experience, an improved cable was designed. The core consisted of seven twisted strands of very pure copper weighing 300 pounds per nautical mile (73 kg/km), coated with Chatterton's compound, then covered with four layers of gutta-percha, alternating with four thin layers of the compound cementing the whole, and bringing the weight of the insulator to 400 lb/nmi (98 kg/km). This core was covered with hemp saturated in a preservative solution, and on the hemp were helically wound eighteen single strands of high tensile steel wire produced by Webster & Horsfall Ltd of Hay Mills Birmingham, each covered with fine strands of manila yarn steeped in the preservative. The weight of the new cable was 35.75 long hundredweight (4000 lb) per nautical mile (980 kg/km), or nearly twice the weight of the old. The Haymills site successfully manufactured 26,000 nautical miles (48,000 km) of wire (1,600 tons), made by 250 workers over eleven months.

Great Eastern and the second cable

The new cable was laid by the ship SS Great Eastern captained by Sir James Anderson.[52] Her immense hull was fitted with three iron tanks for the reception of 2,300 nautical miles (4,300 km) of cable, and her decks furnished with the paying-out gear. At noon on 15 July 1865, Great Eastern left the Nore for Foilhommerum Bay, Valentia Island, where the shore end was laid by Caroline. This attempt failed on 2 August[53] when, after 1,062 nautical miles (1,967 km) had been payed out, the cable snapped near the stern of the ship, and the end was lost.[54]

Great Eastern steamed back to England, where Field issued another prospectus and formed the Anglo-American Telegraph Company,[55] to lay a new cable and complete the broken one. On 13 July 1866, Great Eastern started paying out once more. Despite problems with the weather on the evening of Friday, 27 July, the expedition reached the port of Heart's Content, Newfoundland in a thick fog. Daniel Gooch, chief engineer of the Telegraph Construction and Maintenance Company, who had been aboard the Great Eastern, sent a message to the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Lord Stanley, saying "Perfect communication established between England and America; God grant it will be a lasting source of benefit to our country."[56] The next morning at 9 a.m. a message from England cited these words from the leader in The Times: "It is a great work, a glory to our age and nation, and the men who have achieved it deserve to be honoured among the benefactors of their race." The shore end was landed at Heart's Content Cable Station during the day by Medway. Congratulations poured in, and friendly telegrams were again exchanged between Queen Victoria and the United States.

In August 1866, several ships, including Great Eastern, put to sea again in order to grapple the lost cable of 1865. Their goal was to find the end of the lost cable, splice it to new cable, and complete the run to Newfoundland.[57] They were determined to find it, and their search was based solely upon positions recorded "principally by Captain Moriarty, R. N.", who placed the end of the lost cable at longitude 38° 50' W.[58]

There were some who thought it hopeless to try, declaring that to locate a cable 2.5 mi (4.0 km) down would be like looking for a small needle in a large haystack. However, Robert Halpin, first officer of Great Eastern, navigated HMS Terrible and grappling ship Albany to the correct location.[59] Albany moved slowly here and there, "fishing" for the lost cable with a five-pronged grappling hook at the end of a stout rope. Suddenly, on 10 August, Albany "caught" the cable and brought it to the surface. It seemed to be an unrealistically easy success. During the night, the cable slipped from the buoy to which it had been secured, and the process had to start all over again. This happened several more times, with the cable slipping after being secured in a frustrating battle against rough seas. One time, a sailor even was flung across the deck when the grapnel rope snapped and recoiled around him. Great Eastern and another grappling ship, Medway, arrived to join the search on 12 August. It was not until over a fortnight later, in early September 1866, that the cable was finally retrieved so that it could be worked on; it took 26 hours to get it safely on board Great Eastern. The cable was carried to the electrician's room, where it was determined that the cable was connected. All on the ship cheered or wept as rockets were sent up into the sky to light the sea. The recovered cable was then spliced to a fresh cable in her hold and payed out to Heart's Content, Newfoundland, where she arrived on Saturday, 7 September. There were now two working telegraph lines.[60]

Repairing the cable

Broken cables required an elaborate repair procedure. The approximate distance to the break was determined by measuring the resistance of the broken cable. The repair ship navigated to the location. The cable was hooked with a grapple and brought on board to test for electrical continuity. Buoys were deployed to mark the ends of good cable, and a splice was made between the two ends.[61][62]

Communication speeds

Initially messages were sent by an operator using Morse code. The reception was very bad on the 1858 cable, and it took two minutes to transmit just one character (a single letter or a single number), a rate of about 0.1 words per minute. This was despite the use of the highly sensitive mirror galvanometer. The inaugural message from Queen Victoria took 67 minutes to transmit to Newfoundland, but it took 16 hours for the confirmation copy to be transmitted back to Whitehouse in Valentia.[44]

For the 1866 cable, the methods of cable manufacture, as well as sending messages, had been vastly improved. The 1866 cable could transmit 8 words a minute[63]—80 times faster than the 1858 cable. Oliver Heaviside and Mihajlo Idvorski Pupin in later decades understood that the bandwidth of a cable is hindered by an imbalance between capacitive and inductive reactance, which causes a severe dispersion and hence a signal distortion; see telegrapher's equations. This has to be solved by iron tape or by load coils. It was not until the 20th century that message transmission speeds over transatlantic cables would reach even 120 words per minute. London became the world centre in telecommunications. Eventually, no fewer than eleven cables radiated from Porthcurno Cable Station near Land's End and formed with their Commonwealth links a "live" girdle around the world; the All Red Line.

Later cables

Additional cables were laid between Foilhommerum and Heart's Content in 1873, 1874, 1880, and 1894. By the end of the 19th century, British-, French-, German-, and American-owned cables linked Europe and North America in a sophisticated web of telegraphic communications.

The original cables were not fitted with repeaters, which potentially could completely solve the retardation problem and consequently speed up operation. Repeaters amplify the signal periodically along the line. On telegraph lines this is done with relays, but there was no practical way to power them in a submarine cable. The first transatlantic cable with repeaters was TAT-1 in 1956. This was a telephone cable and used a different technology for its repeaters.

Impact

A 2018 study in the American Economic Review found that the transatlantic telegraph substantially increased trade over the Atlantic and reduced prices.[64] The study estimates that "the efficiency gains of the telegraph to be equivalent to 8 percent of export value".[64]

See also

- 1929 Grand Banks earthquake

- Commercial Cable Company

- Transatlantic telephone cable

- Western Union Telegraph Expedition – overland alternative via Russia

Notes

- 1 2 Guarnieri, M. (2014). "The Conquest of the Atlantic". IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine. 8 (1): 53–56/67. doi:10.1109/MIE.2014.2299492. S2CID 41662509.

- ↑ History of the Transatlantic Cable – Dr. E. O. W. Whitehouse and the 1858 trans-Atlantic cable, retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ↑ Bright, pp. 78–98.

- ↑ Bright, pp. 99–105.

- ↑ Huurdeman, p. 97.

- ↑ Moll, Marita; Shade, Leslie Regan (2004). Seeking Convergence in Policy and Practice: Communications in the Public Interest. Vol. 2. Canadian Center for Policy Alternatives. p. 27. ISBN 0-88627-386-2.

- ↑ Rozwadowski, p. 83.

- 1 2 Lindley, p. 128.

- ↑ Henry Youle Hind; Thomas C. Keefer; John George Hodgins; Charles Robb (1864). Eighty Years' Progress of British North America: Showing the Wonderful Development of Its Natural Resources, Giving, in a Historical Form, the Vast Improvements Made in Agriculture, Commerce, and Trade, Modes of Travel and Transportation, Mining, and Educational Interests, Etc., Etc., with a Large Amount of Statistical Information, from the Best and Latest Authorities. L. Stebbins. pp. 759–.

- 1 2 3 4 Lindley, p. 129.

- ↑ Lindley, p. 127.

- ↑ Bright, p. 14.

- ↑ Cowan, ch. 8.

- ↑ Clayton, p. 30.

- ↑ Kieve, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Cookson pp. 28–29, 96.

- ↑ Hearder, Ian G. (September 2004). "Hearder, Jonathan Nash (1809–1876)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ↑ Burns, p. 140.

- ↑ Cookson, p. 69.

- 1 2 Cookson, p. 73.

- 1 2 Lindley, pp. 134–135.

- 1 2 3 Lindley, p. 135.

- 1 2 3 4 Lindley, p. 130.

- ↑ "History of the Atlantic Cable – Submarine Telegraphy – 1857 – Laying the Atlantic Telegraph From Ship To Shore". Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ↑

- Lindley, p. 134

- Cookson, p. 96

- ↑ Lindley, pp. 130, 133.

- 1 2 3 4 Lindley, p. 134.

- ↑ "History of the Atlantic Cable – Submarine Telegraphy – Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper 1858 Cable News". Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- 1 2 "Manipulation of the Atlantic Telegraph Line. From August 10th to the 1st of September inclusive". Report of the Joint Committee Appointed by the Lords of the Committee of Privy Council for Trade and the Atlantic Telegraph Company, to Inquire Into the Construction of Submarine Telegraph Cables: Together with the Minutes of Evidence and Appendix. Eyre and Spottiswoode: Eyre. 1861. pp. 230–232. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ↑ Harry Granick, Underneath New York, p. 115, Fordham University Press, 1991, ISBN 0823213129.

- ↑ The Curious Story of the Tiffany Cables. See "The Great Transatlantic Cable – 1858". Bill Burns. Atlantic-cable.com. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ↑ Jesse Ames Spencer (1866). "Chapter IX. 1857–1858. Opening of Buchanan's Administration" (Digitised eBook). 'THE QUEEN'S MESSAGE' and 'THE PRESIDENT'S REPLY' (full wording). Vol. 3. Johnson, Fry. p. 542. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Jim Al-Khalili. Shock and Awe: The Story of Electricity, Ep. 2 "The Age of Invention". October 13, 2011, BBC TV, Using Chief Engineer Bright's original notebook. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ↑ "1858 NY Celebration". History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications. Atlantic-cable.com. 10 January 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ↑ Mercer, David (2006). The Telephone: The Life Story of a Technology. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 17. ISBN 9780313332074. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- 1 2 Kieve, p. 109.

- ↑ Lindley, p. 125.

- ↑ Cookson, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Bright, pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Cookson, p. 57.

- ↑ Lindley, pp. 126–127.

- 1 2 3 4 Lindley, p. 133.

- ↑ Arthur C. Clarke. "Voice Across the Sea".

- 1 2 Lindley, p. 139.

- ↑ Clayton, p. 73.

- ↑ Lindley, pp. 133–134.

- ↑ Cookson, p. 96.

- ↑ Lindley, pp. 136–139.

- ↑ Lindley, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Lindley, p. 140.

- ↑ Lindley, pp. 140–141.

- ↑ "History of the Atlantic Cable & Submarine Telegraphy – Great Eastern". www.atlantic-cable.com.

- ↑ Donald E. Kimberlin (1994). "Narrative History". TELECOM Digest.

- ↑ "History of the Atlantic Cable – Submarine Telegraphy – Daniel Gooch". Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ↑ Bill Glover. "Anglo-American Telegraph Company".

- ↑ John R. Raynes (1921), Engines and Men, Goodall & Suddick, p. 89, Wikidata Q115680227

- ↑ "History of the Atlantic Cable – Submarine Telegraphy-Recovery of the Lost Cable". Retrieved 5 August 2008.

- ↑ Bright, Edward B., "Description of the Manufacture, Laying and Working of the Cables of 1865 and 1866...". History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ↑ "Laying the French Atlantic Cable". Nautical Magazine. Brown, Son and Ferguson. 38: 460. 1869. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

To have navigated the ship in a fog so exactly to her proper position was certainly a most wonderful testimony to Captain Halpin's judgment and skill

. - ↑ Bright, pp. 99–105.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ "History of the Atlantic Cable & Submarine Telegraphy – 1915: How submarine cables are made and laid". atlantic-cable.com.

- ↑ "Narrative History Of Submarine Cables". International Cable Protection Committee. 26 February 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- 1 2 Steinwender, Claudia (2018). "Real Effects of Information Frictions: When the States and the Kingdom Became United". American Economic Review. 108 (3): 657–696. doi:10.1257/aer.20150681. hdl:1721.1/121088. ISSN 0002-8282.

References

- Bright, Charles Tilston, Submarine Telegraphs, London: Crosby Lockwood, 1898 OCLC 776529627.

- Burns, Russell W., Communications: An International History of the Formative Years, IET, 2004 ISBN 0863413277.

- Clarke, Arthur C. Voice Across the Sea (1958) and How the World was One (1992); the two books include some of the same material.

- Gordon, John Steele. A Thread across the Ocean: The Heroic Story of the Transatlantic Cable. New York: Walker & Co, 2002. ISBN 978-0-8027-1364-3.

- Clayton, Howard, Atlantic Bridgehead: The Story of Transatlantic Communications, Garnstone Press, 1968 OCLC 609237003.

- Cookson, Gillian, The Cable, Tempus Publishing, 2006 ISBN 0752439030.

- Cowan, Mary Morton, Cyrus Field's Big Dream: The Daring Effort to Lay the First Transatlantic Telegraph Cable, Boyds Mills Press, 2018 ISBN 1684371422.

- Huurdeman, Anton A., The Worldwide History of Telecommunications, Wiley, 2003 ISBN 9780471205050.

- Kieve, Jeffrey L., The Electric Telegraph: A Social and Economic History, David and Charles, 1973 OCLC 655205099.

- Lindley, David, Degrees Kelvin: A Tale of Genius, Invention, and Tragedy, Joseph Henry Press, 2004 ISBN 0309167825.

- Rozwadowski, Helen M. Fathoming the Ocean: The Discovery and Exploration of the Deep Sea, Harvard University Press, 2009 ISBN 0674042948.

Further reading

- Fleming, John Ambrose (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 513–541.

- Hearn, Chester G., Circuits in the Sea: The Men, the Ships, and the Atlantic Cable, Westport, Connecticut: Prager, 2004 ISBN 0275982319.

- Mueller, Simone M. "From cabling the Atlantic to wiring the world: A review essay on the 150th anniversary of the Atlantic telegraph cable of 1866." Technology and Culture (2016): 507–526. online.

- Müller, Simone. "The Transatlantic Telegraphs and the 'Class of 1866' – the Formative Years of Transnational Networks in Telegraphic Space, 1858–1884/89." Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung (2010): 237–259. online

- Murray, Donald (June 1902). "How Cables Unite the World". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. II: 2298–2309. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- Standage, Tom. The Victorian Internet (1998). ISBN 0-7538-0703-3. The story of the men and women who were the earliest pioneers of the on-line frontier, and the global network they created – a network that was, in effect, the Victorian Internet.

External links

- The Atlantic Cable by Bern Dibner (1959) – Complete free electronic version of The Atlantic Cable by Bern Dibner (1959), hosted by the Smithsonian Institution Libraries

- History of the Atlantic Cable & Undersea Communications – Comprehensive history of submarine telegraphy with much original material, including photographs of cable manufacturers samples

- PBS, American Experience: The Great Transatlantic Cable

- The History Channel: Modern Marvels: Transatlantic Cable: 2500 Miles of Copper

- A collection of articles on the history of telegraphy

- Cabot Strait Telegraph Cable 1856 between Newfoundland and Nova Scotia

- American Heritage: The Cable Under the Sea

- Alan Hall – First Transatlantic Cable and First message sent to USA 1856 Memorial

- Travelogue around the world's communications cables by Neal Stephenson

- IEEE History Centre: County Kerry Transatlantic Cable Stations, 1866

- IEEE History Centre: Landing of the Transatlantic Cable, 1866

- Cyrus Field, "Laying Of The Atlantic Cable" (1866)

- The Great Eastern – Robert Dudley Lithographs 1865–66