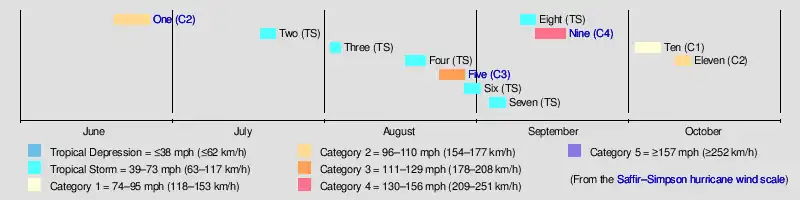

| 1945 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 20, 1945 |

| Last system dissipated | October 13, 1945 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Nine |

| • Maximum winds | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 949 mbar (hPa; 28.02 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 16 |

| Total storms | 11 |

| Hurricanes | 5 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 36 |

| Total damage | At least $82.85 million (1945 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The 1945 Atlantic hurricane season produced multiple landfalling tropical cyclones. It officially began on June 16 and lasted until October 31, dates delimiting the period when a majority of storms were perceived to form in the Atlantic Ocean.[1] A total of 11 systems were documented, including a late-season cyclone retroactively added a decade later. Five of the eleven systems intensified into hurricanes, and two further attained their peaks as major hurricanes. Activity began with the formation of a tropical storm in the Caribbean on June 20, which then made landfalls in Florida and North Carolina at hurricane intensity, causing one death and at least $75,000 in damage. In late August, a Category 3 hurricane on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale struck the Texas coastline, with 3 deaths and $20.1 million in damage. The most powerful hurricane of the season, reaching Category 4 intensity, wrought severe damage throughout the Bahamas and East Coast of the United States, namely Florida, in mid-September; 26 people were killed and damage reached $60 million. A hurricane moved ashore the coastline of Belize in early October, causing one death, while the final cyclone of the year resulted in 5 deaths and $2 million in damage across Cuba and the Bahamas two weeks later. Overall, 36 people were killed and damage reached at least $82.85 million.

Timeline

Systems

Hurricane One

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | June 20 – June 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); 985 mbar (hPa) |

The first tropical cyclone of the 1945 season formed about 120 mi (190 km) southeast of Cozumel around 12:00 UTC on June 20. It tracked north through the Yucatán Channel before turning sharply northeast, simultaneously attaining hurricane intensity early on June 23.[2] Although the crew of a reconnaissance aircraft assessed peak winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) around 18:00 UTC that day,[3] modern reanalysis suggests the cyclone peaked as a Category 2 hurricane with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h).[nb 1] Maximum sustained winds fell to 80 mph (130 km/h) as the system moved ashore near Spring Hill, Florida at 08:00 UTC on June 24, with continued weakening inland. After emerging into the southwestern Atlantic, it regained minimal hurricane intensity and made a second landfall along Harkers Island, North Carolina. The system continued northeast and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone early on June 27, persisting for several days until last documented near Iceland on July 4.[2]

Damage from the hurricane throughout Florida was relatively minor. Citrus trees were stripped of their branches, roadways were washed out, and some telephone and power lines were toppled, temporarily severing communication.[5] Tampa recorded a record 24-hour rainfall total of 10.42 in (265 mm),[3] while precipitation peaked at 13.6 in (350 mm) in Lake Alfred.[6] Statewide, the heavy precipitation was regarded as beneficial in ending one of the worst recorded droughts there.[3] Two tornadoes were spawned; one blew a transformer off a platform and ripped a section of railing off a causeway, while both damaged some homes. Total damage reached $75,000 throughout Miami.[7] Farther north, telephone communications around Georgetown, South Carolina were disrupted, while winds gusted as high as 69 mph (111 km/h) and rainfall peaked at 5.58 in (142 mm) in Charleston.[8] In Wilmington, North Carolina, 8.24 in (209 mm) of rain was observed, causing considerable damage to the city's storm sewer system.[9] Although the core of the cyclone passed east of New England, at least 10,000 telephone lines were downed by the storm. Buildings, crops, and trees were damaged, while low visibility led to a traffic accident that killed a man in Warwick, Rhode Island.[10]

Tropical Storm Two

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | July 19 – July 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1008 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave organized into a tropical depression in the central Gulf of Mexico by 06:00 UTC on July 19. The system moved west-northwest after formation, reaching tropical storm intensity early the next day. Despite a well-established circulation as indicated by weather balloons,[3] peak winds did not exceed 40 mph (64 km/h) throughout the storm's duration. It turned west and then west-southwest offshore the southern Texas coastline, weakening to a tropical depression early on July 22 and dissipating about 30 mi (48 km) offshore six hours later.[2] Although cyclone warnings were issued along the Texas coastline upon the storm's formation, and boats at Aransas Pass were moved into harbors, impact was negligible; winds peaked at 30 mph (48 km/h) with medium to high tides.[11] Squally weather and rough seas were observed along the coastline from Grand Isle, Louisiana to Port Aransas, Texas.[3]

Tropical Storm Three

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 2 – August 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 1005 mbar (hPa) |

Around 00:00 UTC on August 2, the third tropical cyclone of the season formed about 85 mi (137 km) northeast of Barbados. It crossed Dominica into the Caribbean Sea, where the storm attained peak winds of 60 mph (97 km/h) and prompted small craft advisories.[2][12] Missing Puerto Rico to the south, the cyclone then moved ashore west of Santo Domingo in the Dominican Republic at peak strength early on August 4.[3] It dissipated over the island later that day and produced only scattered thundershowers across the region.[2][13]

Tropical Storm Four

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 17 – August 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 999 mbar (hPa) |

Two weeks after the dissipation of Tropical Storm Three, a reconnaissance aircraft confirmed the formation of a new tropical storm in the same vicinity. The cyclone moved west-northwest north of the Caribbean Sea, reaching peak winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) by 12:00 UTC on August 18,[2] just shy of its originally-assessed hurricane intensity.[3] Steady weakening occurred thereafter, and the cyclone weakened to a tropical depression while passing south of the Bahamas before dissipating north of Cuba early on August 21.[2]

Hurricane Five

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 24 – August 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); 963 mbar (hPa) |

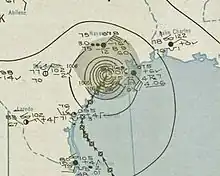

In late August, an area of disturbed weather persisted across the Bay of Campeche, eventually organizing into a tropical depression about 145 mi (233 km) northeast of Veracruz, Mexico by 00:00 UTC on August 24. The system gained steady strength on its north-northwest course, becoming a hurricane early the next day and attaining peak winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) – the first major hurricane of the season – southeast of Corpus Christi, Texas by 12:00 UTC on August 26.[2] At the time, the cyclone was thought to have possessed winds as strong as a 135 mph (217 km/h),[3] but this value was lowered in reanalysis. The hurricane made landfall along Matagorda Island, Texas at peak intensity by 12:00 UTC on August 27 and progressed inland, only slowly weakening to tropical storm intensity early the next morning. The cyclone curved northwest, ultimately dissipating southwest of the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex around 18:00 UTC on August 29.[2]

Though hundreds of miles from Florida, the developing hurricane helped boost St. Petersburg's August rainfall total to its highest in 30 years. Low-lying areas were flooded, sewer systems were backed up, and travel between the city and nearby Tampa was delayed.[14] The storm's impacts in Texas, meanwhile, were regarded as the worst since the 1933 Cuba–Brownsville hurricane. Up to two-thirds of the coastline experienced hurricane-force winds, with a peak gust of 135 mph (217 km/h) recorded in Collegeport. Massive storm tides, as high as 15 ft (4.6 m) in Port Lavaca, inundated coastal locales and eroded up to 50 ft (15 m) of the shore; this was the third largest storm surge documented along the Texas coastline at the time. Rainfall amounts exceeded 30 in (760 mm) along the coastline. Catastrophic losses to crops and livestock were sustained throughout the region. Three deaths occurred in total, including one via a tornado near Houston and two via a capsized fishing vessel offshore Port Isabel, while damage reached $20.1 million.[15][16]

Tropical Storm Six

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | August 29 – September 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 990 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical storm formed southeast of the Nicaragua–Honduras border early on August 29 and tracked northeast. After curving north and then west, the cyclone attained peak winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) over the Gulf of Honduras early on August 31. It moved ashore near Belize City, Belize at peak strength, where heavy rainfall and high tides resulted in flooding of 2–3 ft (0.61–0.91 m) within the city.[3] The system weakened quickly once inland, dissipating just northeast of Ocosingo, Chiapas by 18:00 UTC on September 1.[2]

Tropical Storm Seven

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 3 – September 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1008 mbar (hPa) |

On the heels of Tropical Storm Six, a new tropical depression formed over the western Caribbean Sea by 18:00 UTC on September 3. The fledgling cyclone moved northeast and crossed the western coastline of Cuba near Punta de Cartas before emerging into the Straits of Florida early on September 4. The depression intensified into a tropical storm and attained peak winds of 40 mph (64 km/h), maintaining such strength as it moved ashore near Sanibel, Florida by 00:00 UTC on September 5. It turned abruptly northwest into the northern Gulf of Mexico and weakened to a tropical depression before making a second landfall along the coastline of Mississippi. The weak depression dissipated about 45 mi (72 km) south-southeast of Monroe, Louisiana around 18:00 UTC on September 6.[2] A testament to the weak nature of the storm, only scattered squally weather affected southern Florida, amounting to minor damage to boats in Miami harbors.[3]

Tropical Storm Eight

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 9 – September 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 1009 mbar (hPa) |

Another short-lived tropical storm was first identified about 195 mi (314 km) east of Guadeloupe by 12:00 UTC on September 9. Data from a reconnaissance aircraft indicated the storm intensified slightly to attain winds of 60 mph (97 km/h) by early the next day,[2] in spite of a poorly-defined circulation center.[3] It tracked northwest and then north, passing within 130 mi (210 km) of Bermuda before dissipating around 18:00 UTC on September 12.[2]

Hurricane Nine

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | September 12 – September 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 130 mph (215 km/h) (1-min); 949 mbar (hPa) |

The most powerful cyclone of the season was first noted as an intensifying hurricane east of the Leeward Islands early on September 12. It moved steadily west-northwest, passing north of Puerto Rico as a Category 2 hurricane and moving through the Turks and Caicos Islands at Category 3 intensity. The mature storm attained its peak as a Category 4 hurricane with winds of 130 mph (210 km/h) after crossing Andros, Bahamas and soon began a gradual west-northwest turn. It moved ashore the northern end of Key Largo at 19:30 UTC on September 15, progressing into mainland Florida near Homestead, and whereupon the cyclone became the third strongest hurricane to hit Miami-Dade County, Florida on record.[17] The system then curved north throughout the central portions of the state before emerging offshore and making a second landfall near Savannah, Georgia, with winds of 70 mph (110 km/h). A continued northward track brought the cyclone into the South Atlantic States, where it completed extratropical transition roughly 50 mi (80 km) east-northeast of Danville, Virginia. The post-tropical cyclone fluctuated in strength and was last noted east of Newfoundland on September 20.[2]

On Grand Turk Island, up to three quarters of the structures there were demolished and the remainder sustained at least minimal damage. Heavy damage occurred on Long Island, Bahamas as well. Reports suggested that up to 22 people may have been killed across the Turks and Caicos Islands. In Florida, the highest measured wind gust topped 138 mph (222 km/h) at Carysfort Reef Light. A total of 1,632 residences were destroyed while an additional 5,372 others received damage, particularly near the landfall point in Homestead. Naval Air Station Richmond suffered catastrophic losses when high winds ignited a fire that engulfed 25 blimps, 366 airplanes, and 150 automobiles across three hangars. Although the station's weather equipment failed, an inspection of the hurricane's damage led to the conclusion that gusts may have reached 150 mph (240 km/h) there. Throughout the remainder of the state, communications were severed by downed telephone lines, crops were ruined, thousands of livestock were killed, and 4 people perished.[3] The overall coast of damage reached $60 million.[17] Farther north across the Carolinas, the cyclone inundated a region affected by heavy precipitation in the days before. The Cape Fear River crested at its highest level on record, 68.9 ft (21.0 m), flooding large sections of crop lands and adjacent homes.[18] In Richmond County, Virginia, broken dams led to significant flash flooding.[19]

Hurricane Ten

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 2 – October 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min); 982 mbar (hPa) |

Early on October 2, the tenth tropical storm of the season was noted about 150 mi (240 km) northeast of the Nicaragua–Honduras border. It intensified into a Category 1 hurricane by 00:00 UTC the next day on a general west-northwest track and peaked with winds of 90 mph (140 km/h) 24 hours later,[2] although the crew aboard a reconnaissance aircraft originally estimated 100 mph (160 km/h) sustained winds.[3] The cyclone tracked west-southwest and made landfall north of Punta Gorda, Belize at peak strength, quickly weakening once inland. Crossing Guatemala and Chiapas, the depression paralleled the coastline of Mexico for a time before moving ashore west of Lázaro Cárdenas, Michoacán. The wilting system dissipated over southern Durango by 12:00 UTC on October 7.[2]

Maximum gusts topped 60 mph (97 km/h) on Swan Islands, where hundreds of coconut palm trees and most of the banana trees were toppled. Upon making landfall in Belize, the hurricane flattened up to three-quarters of the homes in Punta Gorda, resulting in one death and many injuries. In Livingston, Guatemala, 40 houses were destroyed,[3] and barges loaded with 10,000 bags of coffee were blown out to sea.[20]

Hurricane Eleven

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| |

| Duration | October 10 – October 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); ≤982 mbar (hPa) |

The final Atlantic hurricane of 1945 was not officially documented until over a decade following the end of the season. Using re-analyzed surface weather maps, as well as recounts from local residents along the storm's path, it was discovered that a tropical depression formed south of Jamaica in the southwestern Caribbean Sea by 12:00 UTC on October 10.[2][21] The compact storm moved north and then north-northeast ahead of a stationary front that existed from the western Atlantic into the Bay of Campeche. It became a minimal hurricane over the Cayman Islands by 00:00 UTC on October 12 and attained its peak at Category 2 intensity with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h) while making landfall along a deserted southern stretch of Cuba. The storm emerged into the Bahamas while maintaining Category 1 strength before becoming intertwined with the frontal zone and transitioning into an extratropical cyclone southwest of Bermuda.[21] The post-tropical storm slowly weakened but persisted until it was absorbed by a large extratropical low near the Azores on October 16.[2]

Due to the hurricane's small size, only fleeting rain and wind was experienced across the Cayman Islands. Cuba bore the brunt of the Category 2 hurricane as it moved ashore near Las Coloradas, where all the mangrove trees were destroyed and sea waters pushed inland. Significant impacts were observed in Jatibonico, where several tanks at a sugar mill were destroyed, a few railroad cars were derailed, and at least one building was demolished. Trees were toppled along the Sierra de Jatibonico, and winds of 70–75 mph (113–121 km/h) were felt in Tunas de Zaza, where the telegraph service was disabled. Four deaths and 200 injuries were documented throughout Cuba, with a damage estimate of $2 million. Tropical storm-force winds were produced throughout the Bahamas, cutting electricity to a number of homes on New Providence. Meanwhile, in Eleuthera, damage was inflicted to small vessels, a number of buildings, and telephone lines as winds reached 70–90 mph (110–140 km/h); one fatality was reported. Roadways were blocked across the island. In nearby Andros, a number of farms and thousands of coconut trees were destroyed.[21]

Other systems

A large extratropical cyclone was first noted over the north central Atlantic on May 23. The system's temperature gradient subsided two days later, possibly indicating a brief transition into a subtropical cyclone, but it ultimately degenerated into a trough by May 26. On August 29, an area of low pressure formed in the central Gulf of Mexico; by 00:00 UTC the next day, a nearby ship recorded sustained winds of 35 mph (56 km/h) and a pressure of 1,006 mbar (1,006 hPa; 29.7 inHg), indicating a high likelihood of a tropical depression. The storm moved ashore in northern Mexico on August 30, producing winds just below gale force and scattered showers in Brownsville, Texas. A few days later, an extratropical cyclone drifted south and then east over the northeastern Atlantic, potentially acquiring subtropical characteristics by September 6; it dissipated two days later. On September 8, a compact low formed at the tail-end of a dissipating stationary front off the coastline of North Carolina. Within the warm sector of an approaching extratropical cyclone, it is likely the system attained tropical depression status before it was last seen east of Nantucket, Massachusetts on September 11.[22]

A small area of low pressure formed north of Honduras on September 26 and is surmised to have developed into a tropical depression before moving ashore two days later. In late September, an extratropical cyclone formed along a front west of the Azores. The low detached from the front and acquired either subtropical or fully tropical characteristics on September 27 before it was engulfed by another cold front the following day. Yet another extratropical low formed along a front in the northeastern Atlantic on October 4. With a broad circulation and minimal temperature gradient, the system may have briefly acquired subtropical qualities on October 7 before it transitioned into an extratropical low again the next day. Finally, on October 19, a closed area of low pressure developed between Miami, Florida and the Bahamas, possibly in connection with a frontal zone. Given the system's compact circulation, it is likely a tropical depression formed and progressed northeast before the low transitioned into an extratropical cyclone over the north central Atlantic.[22]

Season effects

This is a table of all the storms that have formed in the 1945 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their duration, names, landfall(s), denoted in parentheses, damage, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all the damage figures are in 1945 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | June 20 – 27 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (160) | 985 | East Coast of the United States | $75 thousand | 1 | |||

| Two | July 19 – 22 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1008 | Texas, Louisiana | None | None | |||

| Three | August 2 – 4 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1005 | Greater Antilles | None | None | |||

| Four | August 17 – 21 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 999 | Greater Antilles, The Bahamas | None | None | |||

| Five | August 24 – 29 | Category 3 hurricane | 115 (185) | 963 | Texas, Florida | $20.1 million | 3 | |||

| Six | August 29 – September 1 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 990 | Central America | Minimal | None | |||

| Seven | September 3 – 6 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1008 | Gulf Coast of the United States | Minimal | None | |||

| Eight | September 9 – 12 | Tropical storm | 60 (95) | 1009 | None | None | None | |||

| Nine | September 12 – 18 | Category 4 hurricane | 130 (215) | 949 | Leeward Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, Bahamas, Florida, Georgia, The Carolinas | $60 million | 26 | |||

| Ten | October 2 – 7 | Category 1 hurricane | 90 (150) | 982 | Central America, Mexico | Unknown | 1 | |||

| Eleven | October 10 – 13 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (160) | 982 | Greater Antilles, The Bahamas | $2 million | 5 | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 11 systems | June 20 – October 13 |

130 (215) | 949 | $82.85 million | 36 | |||||

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ In 2000, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration enacted the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis project. Through the compilation of previously-unused data, as well as a better understanding of tropical cyclone processes, scientists aim to refine cyclone intensities and tracks within hurricane seasons to create a more accurate Atlantic hurricane database.[4]

References

- ↑ "Gulf Coast Area Prepared for Storm Emergency". Taylor Daily Press. Taylor, Texas. June 19, 1945. p. 6. Retrieved May 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved January 18, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 H.C. Sumner (April 16, 1946). Monthly Weather Review: North Atlantic Hurricanes and Tropical Disturbances of 1945 (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- ↑ "Current Hurricane Data Sets". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved May 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Storm Centered off Brunswick; Full Hurricane". The Palm Beach Post. West Palm Beach, Florida. June 25, 1945. p. 1. Retrieved May 4, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Rainfall Associated with Hurricanes (PDF) (Report). Weather Prediction Center. July 1956. p. 177. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- ↑ Monthly Weather Review: Severe Local Storms, June 1945 (PDF) (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. June 1945. p. 2. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- ↑ "Hurricane Skirts Carolina Coast". Tallahassee Democrat. Tallahassee, Florida. June 25, 1945. p. 1. Retrieved May 4, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Storm Heads for Manteo; Damage Light". Asheville Citizen-Times. Asheville, North Carolina. June 26, 1945. p. 1. Retrieved May 4, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Darien Soldier Saved on Sound". The Hour. Norwalk, Connecticut. June 27, 1945. p. 1. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- ↑ "Tropical Storm Dies Down in Intensity". Big Spring Herald. Big Spring, Texas. July 22, 1945. p. 16. Retrieved May 4, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Tropical Storm Moves Off Shore of Virgin Isles". Fort Lauderdale News. Fort Lauderdale, Florida. August 3, 1945. p. 1. Retrieved May 4, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Tropical Storm has Dissipated". The Brownsville Herald. Brownsville, Texas. August 6, 1945. p. 1. Retrieved May 4, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Storm in Gulf Causes Heavy Rains in City". Tampa Bay Times. St. Petersburg, Florida. August 25, 1945. p. 6. Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- ↑ David M. Roth. Texas Hurricane History (PDF) (Report). Camp Springs, Maryland: Weather Prediction Center. p. 46. Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Some Maximum Surge Records for Texas Storms". Houston, Texas: Weather Research Center. Archived from the original on August 19, 2016. Retrieved May 5, 2017.

- 1 2 Tropical Winds (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Weather Service. National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office in Miami, Florida. Spring 2013. p. 6. Retrieved May 6, 2017.

- ↑ Greg Barnes (September 18, 2018). "What to expect when the Cape Fear River crests?". The Fayetteville Observer. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- ↑ Charles B. Carney; Albert V. Hardy (November 1962). Significant North Carolina Hurricanes (PDF) (Report). Raleigh, North Carolina: United States Weather Bureau. p. 23. Retrieved May 6, 2017.

- ↑ "1 killed, many hurt as storm hits Honduras". The Tennessean. Associated Press. October 5, 1945. p. 1. Retrieved May 6, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 José Fernández Partagás (July 1966). The "Unrecorded" Hurricane of October 1945 (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- 1 2 Christopher W. Landsea; et al. Documentation of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Changes in HURDAT (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 6, 2017.