USS Helena in 1940 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Helena |

| Namesake | City of Helena, Montana |

| Builder | New York Naval Shipyard, Brooklyn, New York |

| Laid down | 9 December 1936 |

| Launched | 28 August 1938 |

| Commissioned | 18 September 1939 |

| Fate | Sunk, Battle of Kula Gulf, 6 July 1943 |

| General characteristics (As built) | |

| Class and type | Brooklyn-class light cruiser |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 608 ft 8 in (185.52 m) |

| Beam | 61 ft 5 in (18.72 m) |

| Draft |

|

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 32.5 kn (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph) |

| Complement | 888 officers and enlisted men |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

| Aircraft carried | 4 × SOC Seagull floatplanes |

| Aviation facilities | 2 × stern catapults |

| General characteristics (1942 refit) | |

| Sensors and processing systems |

|

| Armament |

|

USS Helena was a Brooklyn-class light cruiser built for the United States Navy in the late 1930s, the ninth and final member of the class. The Brooklyns were the first modern light cruisers built by the US Navy under the limitations of the London Naval Treaty, and they were intended to counter the Japanese Mogami class; as such, they carried a battery of fifteen 6-inch (150 mm) guns, the same gun armament carried by the Mogamis. Helena and her sister St. Louis were built to a slightly modified design with a unit system of machinery and an improved anti-aircraft battery. Completed in 1939, Helena spent the first two years of her career in peacetime training that accelerated as tensions between the United States and Japan increased through 1941. She was torpedoed at the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and was repaired and modernized in early 1942.

After returning to service, Helena was assigned to the forces participating in the Guadalcanal campaign in the south Pacific. There, she took part in two major night battles with Japanese vessels in October and November 1942. The first, the Battle of Cape Esperance on the night of 11–12 October, resulted in a Japanese defeat, with Helena's rapid-fire 6-inch battery helping to sink a heavy cruiser and a destroyer. The second, the first night of the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal in the early hours of 13 November, saw a similar defeat imposed on the Japanese; again, Helena's fast shooting helped to overwhelm a Japanese task force that included two fast battleships, one of which was disabled by heavy American fire and sank the next day. Helena sank a destroyer and damaged several others in the action while emerging relatively unscathed. During her tour in the south Pacific, she also escorted convoys carrying supplies and reinforcements to the Marines fighting on Guadalcanal and bombarded Japanese positions on the island and elsewhere in the Solomons.

Following the American victory on Guadalcanal in early 1943, Allied forces began preparations to advance along the Solomon chain, first targeting New Georgia. Helena took part in a series of preparatory attacks on the island through mid-1943, culminating in an amphibious assault in the Kula Gulf on 5 July. The next night, while attempting to intercept a Japanese reinforcement squadron, Helena was torpedoed and sunk in the Battle of Kula Gulf. Most of her crew were picked up by a pair of destroyers and one group landed on New Georgia where they were evacuated the next day, but more than a hundred remained at sea for two days, ultimately making land on Japanese-occupied Vella Lavella. There, they were hidden from Japanese patrols by Solomon Islanders and a coastwatcher detachment before being evacuated on the night of 15–16 July. Helena's wreck was located in 2018 by Paul Allen.

Design

As the major naval powers negotiated the London Naval Treaty in 1930, which contained a provision limiting the construction of heavy cruisers armed with 8-inch (203 mm) guns, United States naval designers came to the conclusion that with a displacement limited to 10,000 long tons (10,160 t), a better protected vessel could be built with an armament of 6 in (152 mm) guns. The designers also theorized that the much higher rate of fire of the smaller guns would allow a ship armed with twelve of the guns to overpower one armed with eight 8-inch guns. During the design process of the Brooklyn class, which began immediately after the treaty was signed, the US Navy became aware that the next class of Japanese cruisers, the Mogami class, would be armed with a main battery of fifteen 6-inch guns, prompting them to adopt the same number of guns for the Brooklyns. After building seven ships to the original design, additional changes were incorporated, particularly to the propulsion machinery and the secondary battery, resulting in the St. Louis sub-class, of which Helena was the second member.[1][2][lower-alpha 1]

Helena was 607 feet 4.125 inches (185 m) long overall and had a beam of 61 ft 7.5 in (18.783 m) and a draft of 22 ft 9 in (6.93 m). Her standard displacement amounted to 10,000 long tons (10,160 t) and increased to 12,207 long tons (12,403 t) at full load. The ship was powered by four Parsons steam turbines, each driving one propeller shaft, using steam provided by eight oil-fired Babcock & Wilcox boilers. Unlike the Brooklyns, the two St. Louis-class cruisers arranged their machinery in the unit system, alternating boiler and engine rooms. Rated at 100,000 shaft horsepower (75,000 kW), the turbines were intended to give a top speed of 32.5 knots (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph). The ship had a cruising range of 10,000 nautical miles (18,520 km; 11,510 mi) at a speed of 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph). She carried four Curtiss SOC Seagull floatplanes for aerial reconnaissance, which were launched by a pair of aircraft catapults on her fantail. Her crew numbered 52 officers and 836 enlisted men.[2][8][5]

The ship was armed with a main battery of fifteen 6 in /47 caliber Mark 16 guns[lower-alpha 2] in five 3-gun turrets on the centerline. Three were placed forward, two of which were placed in a superfiring pair facing forward, with the third being directly pointed aft; the other two turrets were placed aft of the superstructure in another superfiring pair. The secondary battery consisted of eight 5 in (127 mm) /38 caliber dual purpose guns mounted in twin turrets, with one turret on either side of the conning tower and the other pair on either side of the aft superstructure. As designed, the ship was equipped with an anti-aircraft (AA) battery of eight 0.5 in (13 mm) guns, but her anti-aircraft battery was revised during her career. The ship's belt armor consisted of 5 inches on a layer of 0.625 in (15.9 mm) of special treatment steel and her deck armor was 2 in (51 mm) thick. The main battery turrets were protected with 6.5 in (170 mm) faces and they were supported by barbettes 6 inches thick. Helena's conning tower had 5-inch sides.[2][8][5]

Modifications

The main prewar alterations to the ship revolved around her anti-aircraft battery: in 1941, the Navy decided that each member of the Brooklyn class was to be equipped with four quadruple 1.1 in (28 mm) anti-aircraft guns, but the guns were in short supply, and Helena was the only member of the class to have received any of her 1.1 in guns by November 1941. The guns Helena received were placed in the mounts for the .50-cal guns, which were transferred to wheeled carts that could be moved to different firing positions.[9][10]

The ship was reconstructed in 1942 during repairs as a result of damage sustained in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. SG surface search radar, SC air search radar, and FC and FD fire-control radar sets for her main and secondary batteries were installed, along with a new anti-aircraft battery of eight 20 mm (0.79 in) Oerlikon cannon and sixteen 40 mm (1.6 in) Bofors guns in quadruple mounts, along with a director for each Bofors mount.[11][12] Her 1.1 in guns were removed to arm her sister ships Honolulu and Phoenix. The ship's armored conning tower had proved to inhibit good all-around visibility, so it was removed and an open bridge was erected in its place.[9][13] In addition, the weight savings achieved by removing the tower helped to offset the increased weight from the larger anti-aircraft battery.[14] The conning tower, along with those of several of the Brooklyn-class cruisers that were also rebuilt in 1942, were later installed on the reconstructed battleships that had been sunk at Pearl Harbor.[15]

Service history

_anchored_off_Boston_on_15_June_1940_(NH_95815).jpg.webp)

Construction and early career

The US Navy awarded the contract for Helena to the New York Navy Yard on 9 September 1935, and the keel for the new ship was laid down on 9 December 1936. Her completed hull was launched on 28 August 1938 and she was commissioned on 18 September 1939 with the hull number CL-50.[2][16][17] World War II had broken out in Europe in September that year, but for the time being, the United States remained neutral. After entering service, the ship was occupied with sea trials and initial training, and she embarked on a major shakedown cruise abroad on 27 December, bound for South American waters. She stopped in Guantanamo Bay, an American-leased naval base in Cuba, on the way before arriving in Buenos Aires, Argentina, on 22 January 1940; from there, she continued on to Montevideo, Uruguay, on 29 January. While in the latter port, the crew inspected the wreck of the German heavy cruiser Admiral Graf Spee that had recently been scuttled after the Battle of the River Plate the previous month. Helena got underway again in mid-February to return to the United States, again passing through Guantanamo Bay on the way. After returning, she was dry-docked for repairs from 2 March to 14 July.[16][18]

She took part in training exercises and sea trials over the next several months until September, when she was transferred to the Pacific Fleet. She passed through the Panama Canal toward the end of the month and arrived in San Pedro, California, on 3 October. From there, she continued on to Pearl Harbor, Hawaii to join the rest of the fleet, arriving there on 21 October. Over the course of the next year, the fleet spent its time conducting training exercises and shooting practice as tensions with Japan rose over the latter's war against China.[19] During this period, from 14 July 1941 to 16 September, the ship was dry-docked for maintenance at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in California; it was during this period that the ship received her 1.1-inch guns.[20] Helena was slated to be dry-docked for another periodic maintenance in December 1941, and was moored in port with the minelayer Oglala tied alongside on 6 December, awaiting her turn in the shipyard. The ships happened to be moored in the berth normally reserved for the battleship Pennsylvania, which was currently in the dry-dock. The ship's commander was at that time Captain Robert Henry English.[19][17]

World War II

Attack on Pearl Harbor

_capsized_at_Pearl_Harbor%252C_7_December_1941_(80-G-474789).jpg.webp)

On the morning of 7 December, the Japanese launched their surprise attack on the American fleet with a first wave of forty Nakajima B5N torpedo bombers, fifty-one Aichi D3A dive bombers, and fifty B5N high-level bombers, escorted by forty-three Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters.[21] The Japanese expected Pennsylvania to be in her normal berth. Three minutes into the attack, which had begun at 07:55, a B5N torpedo bomber dropped its torpedo at what its pilot expected to be the battleship. The torpedo passed underneath Oglala and exploded against Helena's hull on the starboard side, nearly amidships. The blast tore a hole in the hull that flooded the starboard engine and boiler rooms and severed wiring for the main and secondary guns. The ship's crew raced to their battle stations and two minutes after the torpedo hit, the backup forward diesel generator had been turned on, restoring power to the guns.[17][22] Oglala was less fortunate than Helena, as the blast effect loosened hull plates on the minelayer and caused her to capsize.[23]

The first pilot had mistaken the superimposed silhouettes of the two ships, backlit by the sun, to be Pennsylvania. The second torpedo bomber in the wave closed to within 600 yd (550 m) of Helena and Oglala when the pilot realized the first pilot's mistake, breaking off his attack run and causing two more pilots to do the same. Four other pilots pressed their attacks, but all of their torpedoes missed; by this time, the ship's anti-aircraft guns were beginning to engage the Japanese attackers, forcing one of the bombers to drop their torpedo before they reached an ideal launch position. One of the torpedoes went wide and hit a transformer station, while the other three ran deep and embedded themselves in the harbor floor.[24] During these attacks, one of the fighters strafed the ship, causing little damage.[25]

At the same time that the first wave had begun their attacks, the Japanese aircraft carriers launched a second wave consisting of eighty-one dive bombers, fifty-four high-level bombers, and thirty-six fighters.[21] As Helena's anti-aircraft guns got into action, they helped to fend off further attacks from the second strike wave while other men worked to control flooding by closing the many watertight hatches in the ship.[17][22] The heavy anti-aircraft fire was credited with disrupting the aim of several Japanese bombers, which failed to hit the vessel with an estimated four near misses. Of these, one struck the pier while the other three landed in the water on her starboard side.[25]

Helena's anti-aircraft battery provided a heavy barrage of fire during the attack; she fired approximately 375 shells from her 5-inch guns, around 3,000 rounds from her 1.1-inch guns, and about 5,000 rounds from her .50-cal. guns.[25] She was credited with shooting down six Japanese aircraft,[13] out of a total of twenty-nine aircraft downed in the raid.[21] Twenty-six men were killed in the initial attack and another five later died of their wounds, while another sixty-six were injured but recovered. A significant number of the casualties were the result of the torpedo hit, with many of the remainder from bomb fragments from the near misses.[25]

Two days after the attack, Helena was moved into dry dock No. 2 in Pearl Harbor for an inspection and temporary repairs to allow her to return to the west coast of the United States. Steel plates were welded over the torpedo hole and on 31 December, Helena was re-floated. She got underway for Mare Island for permanent repairs and modifications on 5 January 1942 in company with a convoy bound for California. The vessel arrived in the shipyard on 13 January and was dry-docked six days later. Repair work was completed by 4 July, with initial sea trials taking place on 3 to 4 July; only the directors for the 40 mm guns, still en route from the manufacturer, were left to be fitted. The directors arrived shortly thereafter and were installed on 10 July. Helena then conducted a brief period of training that lasted until 15 July, when she returned to Mare Island to have her SG radar installed.[11] She departed Mare Island later that month, moving to San Francisco where she joined six transports bound for the south Pacific. The transports carried a contingent of Seabees to Espiritu Santo. There, Helena joined Task Force (TF) 64, then in the midst of the fighting around Guadalcanal.[17][26][27]

Guadalcanal Campaign

_off_the_Mare_Island_Naval_Shipyard_on_1_July_1942_(NH_95813).jpg.webp)

Over the course of the next two months, Helena and the rest of TF 64 were occupied with covering reinforcement convoys to support the Marines fighting on Guadalcanal and escorting carrier battle groups in the area. While Helena operated with the carrier Wasp on 15 September, a Japanese submarine attacked the fleet and hit Wasp with three torpedoes, inflicting fatal damage. Helena picked up some four hundred survivors from Wasp and carried them back to Espiritu Santo. Shortly thereafter, Captain Gilbert C. Hoover came aboard the ship to replace English.[17][28] By this time, the task force consisted of Helena, her sister ship Boise, the heavy cruisers San Francisco and Salt Lake City, and the destroyers Farenholt, Duncan, Buchanan, McCalla, and Laffey.[29]

Following the Actions along the Matanikau in late September and early October, the decision was made to send further reinforcements to the island, and so the 164th Infantry Regiment of the Americal Division embarked on a pair of destroyer transports; TF 64 provided the close escort for the vessels, screening them to the west to prevent Japanese forces from intercepting them. By this time, the unit was commanded by Rear Admiral (RADM) Norman Scott, who conducted one night of battle practice with his ships on 8 October before embarking on the operation. The ships patrolled to the south, just out of range of Japanese aircraft based in Rabaul over the course of 9 and 10 October and each day at 12:00 Scott took his ships north to Rennell Island, where they would be in position to reach Savo Island to block a Japanese squadron if it was detected by air. On 11 October, American aerial reconnaissance detected Japanese vessels moving toward the island carrying their own reinforcements, and Scott decided to try to intercept them.[30]

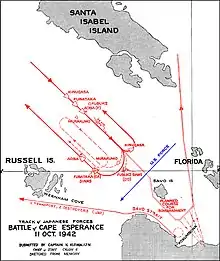

Battle of Cape Esperance

Unknown to Scott, the Japanese had sent a group of cruisers and destroyers to bombard the American garrison on Guadalcanal; this unit, commanded by Rear Admiral Aritomo Gotō, consisted of the heavy cruisers Aoba, Kinugasa, and Furutaka and the destroyers Fubuki and Hatsuyuki. As the two squadrons approached each other in the darkness at the southern end of the Slot shortly before 22:00 on 11 October, three of the four American cruisers launched their floatplanes, but Helena did not receive the instruction from Scott aboard his flagship San Francisco, and so her crew dumped the aircraft overboard to reduce the risk of fire in the event of a battle. By 22:23, the American ships had arranged themselves into a line in the order Farenholt, Duncan, Laffey, San Francisco, Boise, Salt Lake City, Helena, Buchanan, and McCalla; this was despite the fact that Helena and Boise both carried SG radar, which was significantly more effective than the SC sets carried by the other vessels.[31][32] The distance between each ship ranged from 500 to 700 yd (460 to 640 m). Visibility was poor because the moon had already set, leaving no ambient light and no visible sea horizon.[33][34]

Helena's radar operators picked up the oncoming Japanese squadron at 23:25, fixing their position as being 27,700 yd (25,300 m) away at 23:32. Shortly after Helena initially detected the Japanese, Scott had reversed the course of his ships, steaming to the southwest as Gotō's vessels steamed perpendicular to Scott's course. This would place the American squadron in position to cross the T of the Japanese formation. Officers aboard Helena assumed that Scott was aware of the contacts based on his course reversal. By 23:45, the gunnery radar of the American flagship finally detected the Japanese at a range of only 5,000 yd (4,600 m), which was confirmed by lookouts on the American vessels. Hoover requested permission from Scott to open fire, and after receiving what he interpreted as an affirmative answer, he ordered his guns to begin firing at 23:46.[lower-alpha 3] The other ships in the squadron quickly followed Helena's example. Gotō was at that time still unaware of the Americans' presence and his ships were not prepared for action, having assumed that after the Battle of Savo Island, American naval forces would not challenge Japanese warships at night.[34][36][37]

The initial salvos struck Aoba, inflicting serious damage and mortally wounding Gotō, causing further confusion on the Japanese ships. After only a minute of firing, Scott ordered his ships to cease firing because he was concerned they were accidentally shooting at the leading trio of destroyers, which had fallen out of formation during the course reversal. Fire from the American ships did not actually stop at this point, and after clarifying the position of his ships, he ordered TF 64 to resume firing at 23:51. During this period, the captain of Furutaka turned to port to escape the heavy American fire, but reversed course at 23:49 to come to Aoba's aid. This maneuver rewarded Furutaka with numerous shell hits from several warships including Helena, at least one of which detonated the torpedoes in her deck launchers and caused a major fire. Kinugasa also immediately turned to port, but unlike Furutaka, her captain continued to withdraw along with Hatsuyuki, avoiding any damage to his vessel. Fubuki turned to a course parallel with the American squadron; initially targeted by San Francisco and Boise and set on fire, Fubuki then drew heavy fire from most of the other vessels. In the confused, close-range action, either Helena or Boise (the only ships armed with 6-inch guns) accidentally hit Farenholt, causing flooding and a fuel leak that forced her to withdraw from the battle.[38][39][40]

At around midnight, Scott sought to reorganize his squadron to more effectively pursue the Japanese vessels; he ordered his ships to flash their fighting lights and come back into formation. At 00:06, lookouts aboard Helena and Boise spotted the wakes of torpedoes that had been launched by Kinugasa as she withdrew. Shortly thereafter, Kinugasa opened fire with her main battery, inflicting serious damage to Boise. After a short duel between Kinugasa and Salt Lake City, Scott broke off the action as the Japanese continued to flee northeast. Despite having been hit more than forty times, Aoba survived the battle, though Furutaka eventually succumbed to progressive flooding, as did Fubuki; Helena contributed to both vessels' demise. Despite having defeated the Japanese bombardment force, Scott missed a second group of warships carrying reinforcements to Guadalcanal, and they were able to deposit their men and supplies without incident.[41][42]

Shortly after the battle, the new fast battleship Washington was transferred to TF 64, which now came under the command of RADM Willis Lee. By this time, the unit also included Helena, San Francisco, the light cruiser Atlanta, and six destroyers. On 20 October, Helena came under attack from a Japanese submarine while she patrolled between Espiritu Santo and San Cristobal, but the torpedoes missed. Over the course of 21–24 October, Japanese land-based reconnaissance aircraft made repeated contacts with TF 64 as a Japanese fleet approached the area, but in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands that began on the 25th, the Japanese concentrated their air attacks on the American carriers of TF 17 and 61 and Lee's ships saw no action. On 4 November, Helena was back off Guadalcanal to provide fire support during the Koli Point action. Helena, San Francisco, and the destroyer Sterett shelled Japanese positions as they came under attack from elements of the 164th Infantry Regiment and the 8th Marines, ultimately annihilating the Japanese defenders by 9 November.[17][43][44]

Naval Battle of Guadalcanal

In early November, both sides began preparations to resupply their forces fighting on and around Guadalcanal. An American convoy carrying 5,500 soldiers and supplies was organized, to be covered by TF 16, centered on the carrier Enterprise; Washington was detached from TF 64 to strengthen the covering force and the cruiser unit was reorganized as TF 67.4 and assigned as the close escort. Commanded by RADM Daniel J. Callaghan, the unit now included, in addition to Helena, the heavy cruisers San Francisco and Portland, the light cruisers Atlanta and Juneau, and the destroyers Cushing, Laffey, Sterett, O'Bannon, Aaron Ward, Barton, Monssen, and Fletcher. Overall command rested with RADM Richmond K. Turner. Meanwhile, the Japanese had assembled a convoy of their own carrying 7,000 men and supplies for the army already on Guadalcanal; it was to be supported by a bombardment force of two fast battleships, a light cruiser, and eleven destroyers. A total of four heavy and one light cruisers and six destroyers would cover the convoy.[45][46]

On 12 November, Callaghan's ships and their transport vessels arrived off Guadalcanal, and while they unloaded, a Japanese artillery battery opened fire on the transports. Helena and then some of the destroyers returned fire to suppress the Japanese gunners. A Japanese airstrike interrupted the work; two ships were damaged but Helena emerged unscathed. Reconnaissance aircraft detected the approach of the Japanese bombardment force, the convoy, and a detached group of destroyers. Turner believed that the Japanese aimed to either attack TF 67.4 and the transports as they withdrew that night or to bombard the Americans on Guadalcanal; he decided to keep Callaghan's unit off Guadalcanal and to send the convoy off with an escort of just three destroyers and two destroyer minesweepers, as TF 16 was too far south to be able to reach the area. Callaghan escorted the convoy through Lengo Channel before turning back west to position his ships between the Japanese squadron and the garrison on Guadalcanal. The approaching Japanese force, commanded by RADM Hiroaki Abe, centered on the battleships Hiei and Kirishima.[17][47][48]

Callaghan arranged his ships in a single column, as Scott had done at Cape Esperance, and he similarly failed to realize the advantage that the SG-radar-equipped ships provided, eschewing those vessels so-equipped for San Francisco. Scott had transferred to Atlanta, which did not mount an SG, but it was placed as the frontmost cruiser. Abe's ships reached the area off Cape Esperance at around 01:25 on 13 November, by which time his vessels had fallen into disarray due to bad weather that greatly hampered visibility. The destroyers he believed were screening his advance were in fact out of position. Abe was aware of Callaghan's presence off Guadalcanal earlier in the day, but did not know his current whereabouts. At 01:30, he received a report from observers that there were no American vessels off Lunga Point, leading him to order his ships to begin preparations for a bombardment. By this time, Helena had already picked up Abe's ships six minutes before at a distance of 27,100 yd (24,800 m). Callaghan was not aware, as San Francisco had not yet detected the Japanese.[49]

Both sides' destroyers encountered each other at 01:42; continued confusion on Callaghan's part led to contradictory orders that threw the American squadron into disarray just as the two forces collided. In the ensuing close-range melee, he ordered "odd ships fire to starboard, even ships fire to port",[50] although he had not assigned any numbering system beforehand. Abe received incomplete reports from his destroyers, causing him to hesitate briefly before ordering his ships to open fire at 01:48. As the American and Japanese ships engaged each other in the chaotic battle, Helena initially engaged the destroyer Akatsuki, disabling her searchlight but drawing return fire that did insignificant damage. Bombarded by several other vessels, Akatsuki exploded under heavy fire and quickly sank. Helena then shifted fire to the destroyer Amatsukaze at 02:04, only to be forced to check her fire when San Francisco passed between the two vessels. Helena nevertheless scored several hits that forced Amatsukaze to disengage; the Japanese destroyer was only saved from destruction by an attack by the destroyers Asagumo, Murasame, and Samidare that caused Helena to engage them. Murasame received a hit that disabled one of her boiler rooms, forcing her to withdraw as well, while Samidare was set on fire.[51][52][53]

During this period, one of her 40 mm guns fired at the cruiser Nagara as she steamed in the opposite direction. Helena then continued to maneuver among both sides' burning vessels, firing on a number of retreating Japanese vessels.[54] As San Francisco, which had been badly damaged by Hiei, continued on through the melee, Helena turned to follow her to try to protect her from further harm.[55] In the course of the 38-minute action, the American squadron was badly damaged and both Callaghan and Scott were killed in the confused fighting, the latter by friendly fire from San Francisco. Helena emerged relatively unscathed, having received five hits that did negligible damage and killed one man. Two American destroyers were sunk, three more were disabled, as were two cruisers. In return, Hiei was badly damaged and would later be scuttled after repeated American air attacks the next day prevented her withdrawal; one destroyer had been sunk and a second was badly damaged. And more importantly, Callaghan's ships had prevented Abe from bombarding the airfield on Guadalcanal.[56]

Hoover, the senior surviving officer in the shattered American squadron, ordered all vessels still in action to withdraw to the southeast at 02:26 while the Japanese retreated in the opposite direction. Hoover collected San Francisco, Juneau, Sterett, and O'Bannon and escorted them south. At 11:00, the Japanese submarine I-26 fired a spread of torpedoes at San Francisco that missed, but one hit Juneau. The torpedo detonated one of the ship's magazines and combined with the damage she had sustained the previous night, caused her to rapidly sink. Hoover decided that Helena was too valuable to risk stopping to pick up what he assumed to be very few survivors, and the other vessels in the group were too damaged to stop either. He instead signaled to a passing B-17 bomber, but the report of Juneau's fate was not delivered promptly, preventing other vessels from attempting rescue operations. Admiral William Halsey subsequently relieved Hoover of command, citing his failure to ensure a prompt report of the sinking was made, to attack the submarine, or to mount rescue operations. After the war, Halsey expressed regret over the episode, noting that Hoover had been exhausted by the previous night's fighting and that he had been motivated by the need to preserve his ship and those under his temporary command.[57][58][59] Captain Charles P. Cecil replaced Hoover as the ship's commander.[60]

Operations in 1943

_firing_during_the_Munda-Vila_Bombardment%252C_13_May_1943_(NH_76496).jpg.webp)

Beginning in January 1943, Helena took part in several attacks on Japanese positions on the island of New Georgia in preparation for the planned New Georgia campaign.[17] The first of these took place from 1 to 4 January, when Helena (still as part of TF 67) covered a group of seven transports carrying elements of the 25th Infantry Division to Guadalcanal. The unit at that time included six other cruisers and five destroyers, and was commanded by RADM Walden L. Ainsworth. Ainsworth left four cruisers and three destroyers to cover the convoy on the 4th, taking Helena, her sisters St. Louis and Nashville, and two destroyers to bombard Munda in the early hours of 5 January. The ships fired a total of some 4,000 shells, but inflicted little significant damage to the Japanese airfield. The ships returned to Guadalcanal at 09:00 and began recovering their reconnaissance floatplanes when a Japanese airstrike arrived and damaged two of the other cruisers, though Helena was not targeted. The ship had received the new 5-inch shells fitted with proximity VT fuses, and her use marked the first time they were used successfully in combat.[61][62]

Helena and the rest of her unit then returned to Espiritu Santo to refuel and replenish ammunition, remaining there until the morning of 22 January.[63] Halsey had ordered Ainsworth to make an attack on Vila on the island of Kolombangara to neutralize the airfield there, and on 23 January he conducted a feint toward Munda to throw off Japanese aircraft who might have launched night torpedo attacks against his vessels. As at Munda, Ainsworth left a pair of cruisers and three destroyers to provide distant support while he took Helena, Nashville, and four destroyers into Kula Gulf to shell the airstrip. A "Black Cat" PBY Catalina provided spotting support while the two cruisers fired around 3,500 shells from the main and secondary gun, inflicting significant damage on the airfield and equipment. The Japanese launched group of eleven floatplanes to scout for Ainsworth's cruisers while a second group of thirty Mitsubishi G4M bombers, but the American ships used rain squalls to evade the floatplanes, along with long-range 5-inch fire directed by the SC and FD radars to keep the aircraft at bay. At dawn, a group of five P-38 fighters arrived to escort the ships during their continued withdrawal.[64][65]

%252C_USS_Honolulu_(CL-48)_and_USS_Helena_(CL-50)_maneuvering_off_Espiritu_Santo_on_20_June_1943_(80-G-57073).jpg.webp)

On 25 January, Helena and the rest of the squadron arrived back in Espiritu Santo.[66] Helena continued to operate with TF 67, patrolling for Japanese vessels and escorting convoys to Guadalcanal as that campaign ground on into February.[17] She was present as part of the distant support for the convoy operation that resulted in the Battle of Rennell Island on 29–30 January, but TF 64 was too far south to come to the aid of TF 18 during the action.[67] On 11 February, the submarine I-18 attempted to torpedo Helena while cruising off Espiritu Santo, but the cruiser's escorting destroyers, Fletcher and O'Bannon, sank the submarine with assistance from one of Helena's Seagull floatplanes. Helena thereafter went to Sydney, Australia, on 28 February, arriving there on 6 March for an overhaul. She was taken to the Sutherland Dock in the Cockatoo Island Dockyard on 15 March for repair work that lasted two days. She then got underway on 26 March to return north to Espiritu Santo to resume bombardment operations against New Georgia as part of what was now designated TF 68.[42][68][69]

Helena arrived in Espiritu Santo on 30 March and rejoined Ainsworth's unit. As the preparations for the New Georgia campaign increased, the ships made repeated patrols into the Slot. Ainsworth's cruisers were also occupied with extensive training for the upcoming operations. While off Guadalcanal refueling from a tanker, Helena received instructions to get underway as quickly as possible, as a large Japanese airstrike was detected on radar. She and the rest of the cruiser unit steamed to the northwest of Savo Island to avoid the raid; they escaped damage, but the attack forced the Americans to cancel the planned cruiser patrol that night. On the night of 12–13 May, Ainsworth took his cruisers to shell Vila and Munda. Helena was tasked with bombarding the former and she fired a total of 1,000 shells at the island during the attack.[70]

The invasion of New Georgia began on 30 June; Helena and the rest of TF 68 patrolled at the northern end of the Coral Sea; at that time, she cruised with St. Louis, Honolulu, and their escorting destroyer screen that consisted of O'Bannon, Nicholas, Chevalier, and Strong. By 1 July, the ships were about 300 nmi (560 km; 350 mi) south of New Georgia, and on 3 July they reached Tulagi, where a false report of a Japanese airstrike briefly sent the ships' crews to their battle stations. The Allied plan called for a second landing on New Georgia in the Kula Gulf on the northeastern side of the island. A landing here would block the resupply route for the Japanese forces fighting on the island and it would also deny their use of the gulf to escape once they were defeated, as they had done on Guadalcanal.[71]

Landing at Rice Anchorage

Having attacked the Japanese positions around the Kula Gulf on several occasions, Ainsworth knew that the Japanese would be expecting further attacks as the New Georgia campaign got underway. He instructed the cruiser commanders to expect Japanese naval forces to intervene, to be prepared to evacuate damaged ships, and if necessary, to beach badly damaged vessels in the Rice Anchorage. On 4 July, the American invasion force—assault troops loaded aboard destroyer transports—departed Tulagi at 15:47, with Honolulu in the lead, followed by St Louis and Helena. The four destroyers took up positions around them to screen for submarines, while the destroyer transports sailed independently. At the same time, a group of three Japanese destroyers, Niizuki, Yūnagi, and Nagatsuki, left Bougainville with a contingent of 1,300 infantry aboard to reinforce the garrison on New Georgia.[72]

Nicholas and Strong reached Kula Gulf first, scanning it with their radar and sonar sets to determine if any Japanese warships were in the area. The cruisers and other two destroyers then entered the gulf to prepare to bombard Japanese positions at Vila. Honolulu opened fire first 00:26 on 5 July and Cecil ordered Helena's gunners to follow suit ninety seconds later. Black Cats circling overhead coordinated the ships' fire. The other vessels quickly joined in the bombardment, which lasted about fourteen minutes before the American column turned east to move to the Rice Anchorage to shell targets there. After six minutes of shooting, the ships departed, Helena having fired over a thousand rounds of 6- and 5-inch shells in the two bombardments. During the latter period, Helena's crew noted shell splashes from Japanese artillery batteries near the ship, but none of the American vessels were hit. Unbeknownst to the Americans, the three Japanese destroyers had arrived in the gulf while they were still shooting. Illuminated by the gun flashes, the American vessels were quickly identified by the Japanese over 6 nmi (11 km; 6.9 mi) away.[73]

_at_a_South_Pacific_base%252C_circa_in_1943_(NH_95814).jpg.webp)

The transport group then entered the gulf and steamed close to the shore to prevent intermingling with Ainsworth's squadron, which had turned north at 12:39 to leave the gulf. Captain Kanaoka Kunizo, the senior destroyer commander in charge of the reinforcement operation, decided to withdraw as well to avoid engaging a superior force with his ships loaded with soldiers and supplies. Niizuki, the only radar-equipped destroyer, directed the aim of all three vessels, which launched a total of fourteen Long Lance torpedoes before withdrawing at high speed to escape back to Bougainville. One of these torpedoes struck Strong, which was still stationed at the entrance of the gulf on sentry duty. The destroyer was fatally damaged, but the attack alerted Ainsworth that there were Japanese warships in the area. O'Bannon and Chevalier were detached to pick up survivors while Ainsworth prepared to search for the submarine he assumed to have been responsible, as none of his ships had detected the three Japanese destroyers on their radars. Strong sank at 01:22, with 239 of her crew taken off by the other destroyers, though some additional survivors were missed in the darkness and were later picked up by the transport group. Ainsworth's ships then resumed their cruising formation at 02:15 for the voyage back to Tulagi.[74]

During the bombardment, the shell hoist for the left gun in turret No. 5 broke down, while propellant cases repeatedly jammed in turret No. 2; work on the turrets began immediately as the vessels steamed back to Tulagi. The ammunition hoist was quickly restored to working order, but the gun in turret No. 2 took more than five hours of work before the jammed case could be removed and replaced with a modified short case that allowed the shell that was still in the gun to be fired, clearing it for normal use. At 07:00, the destroyer Jenkins joined the squadron, which reached Tulagi in the early afternoon, where the ships immediately began refueling. Shortly thereafter, Ainsworth received orders from Halsey to return to Kula Gulf, as reconnaissance aircraft had spotted Japanese destroyers departing from Bougainville to attempt the planned reinforcement run that he had inadvertently disrupted the night before. Ainsworth was to intercept the destroyers and prevent the landing of more Japanese forces on the island. He ordered the ships to end refueling and prepare to get underway; Jenkins replaced Strong and the destroyer Radford took the place of Chevalier, which had been damaged in an accidental collision with the sinking Strong.[75]

Battle of Kula Gulf

_firing_during_the_Battle_of_Kula_Gulf%252C_6_July_1943_(80-G-54553).jpg.webp)

Since the previous night's reinforcement run had been aborted, the Japanese assembled a group of ten destroyers to make a larger effort the next night. Niizuki—now the flagship of Rear Admiral Teruo Akiyama—and the destroyers Suzukaze and Tanikaze were to escort the other seven destroyers—Nagatsuki, Mochizuki, Mikazuki, Hamakaze, Amagiri, Hatsuyuki, and Satsuki—carried 2,400 troops and supplies. Meanwhile, the American force intending to block their advance had formed up by 19:30 and began the voyage back up the Slot. As the Americans steamed toward Kula Gulf, the crews got their vessels ready for action, including closing all of the watertight doors to reduce the risk of flooding and turning off all lights to prevent detection by the Japanese.[76]

The American squadron passed Visuvisu Point at the entrance to the gulf early on 6 July, at which point the vessels reduced speed to 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph). Visibility was poor owing to heavy cloud cover. Ainsworth had no information as to the specific composition or location of the Japanese force, and patrolling Black Cats could not detect them in the conditions. The Japanese destroyers had already entered the gulf and begun unloading their cargoes; Niizuki detected the American ships on her radar at 01:06 at a range of about 13 nmi (24 km; 15 mi). Akiyama took his flagship, Suzukaze, and Tanikaze to observe the Americans at 01:43 while the other destroyers continued to disembark the soldiers and supplies; by that time, Ainsworth's ships had already detected the three ships off Kolombangara at 01:36. As the two sides continued to close, Akiyama recalled the other destroyers to launch an attack. The American vessels transitioned into a line ahead formation, with Nicholas and O'Bannon ahead of the cruisers; the line turned left to close the range to the Japanese vessels before turning right to move toward an advantageous firing position.[77]

The American radars picked up Akiyama's escort detachment along with another group of destroyers that was racing to join him; Ainsworth decided to attack the first group and then turn about to engage the second. At about 01:57, the American vessels opened up with radar-directed rapid fire. Between the three cruisers, they fired around close to 1,500 shells from their 6-inch batteries in the span of just five minutes. Helena quickly expended the flashless propellant charges that had been kept after the previous night's bombardment mission, thereafter transitioning to normal smokeless propellant, which created large flashes every time the guns fired. Helena initially targeted the leading destroyer—Niizuki—with her main battery while her 5-inch guns engaged the following vessel. Niizuki also received heavy fire from the other American ships and was quickly sunk, taking Akiyama down with her. Helena then shifted fire to the next closest vessel, but by that time, Suzukaze and Tanikaze had both launched eight torpedoes at the American line. They then fled to the northwest, using heavy smoke to conceal themselves while their crews reloaded their torpedo tubes. Both destroyers received minor hits during their temporary withdrawal but were not seriously damaged.[78]

_in_the_Battle_of_Kuly_Gulf%252C_6_July_1943_(C_l5001).jpg.webp)

Ainsworth instructed his ships to turn to the right at 02:03 to begin engaging the second group of destroyers, but shortly thereafter three of Suzukaze's or Tanikaze's torpedoes struck Helena on the port side, inflicting serious damage. The first torpedo hit about 150 ft (46 m) from the bow, abreast of the forward-most turret about 5 ft (1.5 m) below the waterline. It caused a major explosion that may have been the result of a magazine detonation. The blast destroyed the No. 1 turret, tore open the hull almost to the keel, and severed the bow from the rest of the hull. The rest of the hull began to flood as the force of the blast collapsed bulkheads below turret No. 2. But even after the severe damage inflicted by the first torpedo, the aft main guns continued to fire, and the ship had not yet been fatally damaged. She remained able to steam at 25 knots despite the increased drag.[79]

Two minutes after the first torpedo hit, the second and third torpedoes struck the ship in quick succession, much lower in the hull than the first had hit, as much as 15 ft (4.6 m) below the waterline. This was below where the ship's belt armor might have reduced the scale of damage inflicted. These hit further aft in the machinery spaces, breaking the keel, flooding the forward engine and boiler rooms, and breaching bulkheads that allowed water into the aft engine room. The flooding disabled the ship's engines and left her immobilized and without electrical power. Another gaping hole had been blasted into the hull, which exacerbated the flooding caused by the first hit. It quickly became clear that Helena would not be able to survive these hits, and two minutes after the third hit, Cecil gave the order to abandon ship. He remained on the bridge with a signalman who attempted to flash a distress message with a signal lamp to no avail. Cecil then ordered another man to dump classified documents overboard before he ordered those still on the bridge to evacuate as well.[80]

.jpg.webp)

With the keel having been broken by the second and third hit, the girders that supported the hull structure began to buckle, collapsing the entire structure amidships and breaking the hull in half. The center third of the ship quickly sank but the bow and stern remained afloat for some time before flooding caused them both to point upward as they filled with water. Ainsworth and the other vessels' captains were not immediately aware that Helena had been disabled owing to the course change, the general confusion that resulted from heavy smoke and gunfire during the battle, and the fact that most attention was directed at the oncoming second group of Japanese destroyers. In the ensuing action, several of the Japanese destroyers were hit and forced to disengage, after which Ainsworth attempted to reorganize his force at around 02:30. He quickly realized that Helena was not responding to radio messages and ordered his ships to begin searching for the missing cruiser. At 03:13, Radford's radar picked up a contact some 5,000 yd (4,600 m) away. The destroyer closed with it and confirmed it was Helena's bow pointing up, out of the water.[81]

Survivors

_steaming_into_Tulagi_Harbour_with_468_survivors_form_USS_Helena_(CL-50)_on_6_July_1943.jpg.webp)

Ainsworth ordered Radford to immediately begin the search for survivors and shortly thereafter instructed Nicholas to join the rescue operation. Ainsworth ordered the destroyers to proceed to the Russell Islands by dawn to avoid being attacked by Japanese aircraft. The remaining pair of destroyers screened Honolulu and St. Louis as they withdrew to avoid the possibility of a retaliatory Japanese air attack. Nearly a thousand men were in the water, clinging to life rafts and waiting to be picked up by the destroyers, which reached the men at 03:41. Some men had brought flashlights when they abandoned Helena to signal their position to the destroyers. As the destroyers moved into position, their crews hung nets over the sides for survivors to climb. But shortly after the rescue effort began, Nicholas' radar operators detected a contact approaching at high speed; both she and Radford broke off the rescue operation to prepare to engage Suzukaze and Tanikaze, both of which had turned northwest to reload their tubes after torpedoing Helena. They had returned southeast to search for Niizuki but after failing to locate her, they withdrew, having come within 13,000 yd (12,000 m) of Nicholas.[82]

With the Japanese destroyers having departed, Nicholas and Radford returned to resume rescue operations at 04:15. The destroyers lowered their whaleboats to assist with the search for survivors. At 05:15, the destroyers' radar sets picked up Amagiri approaching; the latter was also searching for Niizuki when lookouts spotted the two American destroyers. Amagiri turned to engage as Nicholas and Radford did the same. Nicholas and Amagiri launched torpedoes at each other before closing and engaging with guns before Amagiri broke off and disengaged to the west. During the short engagement, the whaleboats continued to search for Helena survivors. At around 06:00, the destroyers had returned, but another radar contact—Mochizuki—again prompted their departure. A short skirmish at long range produced no results apart from further delaying rescue operations. In light of Ainsworth's order to avoid being caught by Japanese aircraft and with daylight fast approaching, Nicholas and Radford withdrew, leaving four of their whaleboats behind to help ferry men to American positions on New Georgia. In the course of the night's operations, Nicholas had picked up 291 while Radford had rescued 444.[83]

Cecil, who had survived the sinking and refused to be pulled aboard one of the destroyers, instead took command of the whaleboats that remained behind. He supervised the loading of three of the boats (the fourth had broken its rudder and was of little use) to ensure that none became overloaded and capsized, and directed their route out of the gulf. Each whaleboat pulled a raft. Cecil sought to bring the flotilla away from Japanese-occupied Kolombangara to avoid drawing enemy fire. After sailing for much of the day, the boats finally reached a beach thought to be near American lines, so the boats got as close to shore as they could and the men waded ashore. They had landed at Menakasapa, a small peninsula on the northwestern side of New Georgia, some seven miles north of American lines. The men remained there overnight, as it was too late to try to pass through the dense jungle. In the meantime, another pair of destroyers, Woodworth and Gwin arrived in Kula Gulf to search for survivors from Helena early on the morning of 6 July. They combed the waters at the mouth of the gulf before observers aboard the destroyers spotted the men on the beach. Gwin sailed as close to the beach as she could get at 07:45, while Woodworth covered her approach. After setting fire to the whaleboats, the Helena survivors—88 men in total—were picked up by Gwin and arrived back in Tulagi at 15:20 that day.[84]

A significant number of men were still in the water; some life rafts remained in the area, while a number of men had climbed onto the still-floating bow or clung to pieces of floating wreckage. A B-24 Liberator heavy bomber passed the area at low altitude to search for survivors and its pilot reported seeing the men who had climbed aboard the floating bow along with other groups in the water. The bomber also dropped three life rafts, one of which sank. The survivors were subjected to brutal conditions while at sea: few provisions, no shelter from the sun, and no warmth at night when temperatures plummeted. As the day wore on, a group of about 50 men took two rafts in an attempt to reach Kolombangara, but the current proved to be too strong for them to overcome. As the day wore on, the groups of men began to drift apart; the men in one of the rafts rigged an improvised sail in an attempt to reach Vella Lavella, the next island to the west of Kolombangara. Other groups of men were pulled there by the current; as the men reached the coral reef that surrounded the island on 8 July, they were met by locals who helped pull the men to shore and put them in contact with the coastwatcher station.[85]

The coastwatchers organized a relief effort to bring the men inland to avoid the Japanese garrison and the patrols that routinely swept the coastal areas. The Solomon Islanders gathered the groups of men as they made landfall over the course of late 7 to early 8 July and took some of them—104 in total—to the house of a Chinese merchant in the interior of the island. Others were collected at two different points on the island to hide the men from the Japanese; these two groups numbered 50 and 11, respectively. The coastwatchers contacted their superior on Guadalcanal and informed him of the situation on the island. Turner's staff there immediately began making plans to launch a rescue operation, though the number of men to be retrieved from an enemy-occupied island complicated the effort, as the typical methods, via submarine or PT boat, would not be able to accommodate the 165 men on Vella Lavella. They settled on using a pair of destroyer transports to evacuate the men, escorted by eight destroyers. Allied naval forces had not yet penetrated as far as Vella Lavella during the campaign, which brought them dangerously close to strong Japanese naval and air forces.[86]

The plan called for the two smaller groups, both of which were located further north than the main group, to meet inland and proceed to the coast where they would signal the waiting transports. The main group of survivors would proceed to a different evacuation point. The operation was initially planned for 12 July, but reports that Japanese vessels were operating in the area forced a postponement until the night of 15 July (and led to the Second Battle of Kula Gulf). Four destroyers took up a defensive position to the northwest to block a possible attack by Japanese forces while the rest of the force steamed to the south of Kolombangara and then north through the Vella Gulf. At 01:55 on 16 July, the men flashed the recognition signal to the waiting transports, which lowered three Higgins boats to ferry the men to the vessels. Along with the Helena survivors, the boats evacuated a downed American pilot and a captured Japanese pilot before the units moved south to the other evacuation point. Again the Higgins boats ferried the group to the transports, along with several Chinese merchants and their families. The flotilla arrived back in Tulagi that afternoon and disembarked the survivors, who were then transferred to the French colony of New Caledonia, where they met the men who had been pulled from the water on the night of the sinking. Out of a crew of almost 1,200, 168 men were killed, either during the battle or while the men were adrift.[87]

Aftermath

A memorial was erected in Helena, Montana to commemorate both cruisers named Helena, CL-50 and CA-75, including artifacts from both vessels.[88]

The wreck was discovered on 11 April 2018 by the research ship RV Petrel, operated by Paul Allen during an expedition to the Solomons to search for the wrecks of warships sunk during the fighting there. Allen confirmed the identity of the wreck through the hull number still visible on the stern. The wreck lies at a depth of about 2,820 ft (860 m).[88]

Footnotes

Notes

- ↑ Helena and St. Louis are sometimes considered to be a distinct class separate from the rest of the Brooklyns,[3] as the US Navy classified them as such.[4] But the majority of naval historians describe them as either part of the Brooklyn class with no distinction,[2][5][6] or as a sub-class,[7] so this article follows that approach.

- ↑ /47 refers to the length of the gun in terms of calibers. A /47 gun is 47 times long as it is in bore diameter.

- ↑ Hoover requested permission to fire with the General Signal Procedure (GSP) request "Interrogatory Roger" (which meant "are we clear to act?"). Scott replied with "Roger", only indicating that he had received Hoover's message, but Hoover interpreted it an affirmative, as according to the GSP, an unqualified "roger" also meant to open fire.[35]

Citations

- ↑ Whitley, pp. 248–249.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Friedman 1980, p. 116.

- ↑ Silverstone, p. 29.

- 1 2 3 Whitley, p. 248.

- ↑ Terzibaschitsch, p. 20.

- ↑ Bonner, p. 55.

- 1 2 Friedman 1984, p. 475.

- 1 2 Whitley, p. 249.

- ↑ Wright, pp. 23, 29.

- 1 2 Wright, pp. 33, 36.

- ↑ Domagalski, p. 2.

- 1 2 Bonner, p. 57.

- ↑ Wright, p. 39.

- ↑ Friedman 1980, p. 92.

- 1 2 Wright, p. 24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 DANFS.

- ↑ Bonner, pp. 55–56.

- 1 2 Bonner, p. 56.

- ↑ Wright, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Rohwer, p. 122.

- 1 2 Bonner, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Zimm, p. 182.

- ↑ Zimm, p. 160.

- 1 2 3 4 Helena Report.

- ↑ Bonner, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Hornfischer, pp. 141–143.

- ↑ Bonner, p. 58.

- ↑ Frank, p. 297.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 292–296.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 294, 296–298.

- ↑ Rohwer, p. 201.

- ↑ Cook, pp. 20, 26, 36.

- 1 2 Morison, pp. 152–153.

- ↑ Frank, p. 301.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 299–302.

- ↑ Cook, pp. 58–60.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 302–304.

- ↑ Cook, pp. 68–70, 83–84.

- ↑ Morison, pp. 158–160.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 304–307, 312.

- 1 2 Whitley, p. 253.

- ↑ Rohwer, pp. 201, 205–207.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 378, 420.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 429–430, 435.

- ↑ Rohwer, pp. 210–211.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 430–436.

- ↑ Rohwer, p. 211.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 436–438.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 438–440.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 440–446, 449–450.

- ↑ Morison, pp. 242–243.

- ↑ Hammel, pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 446.

- ↑ Hammel, p. 234.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 443–446, 452, 454–456, 459.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 451, 456–457.

- ↑ Morison, p. 257.

- ↑ Kilpatrick, pp. 101–103.

- ↑ Domagalski, p. 3.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 548–549.

- ↑ Rohwer, p. 223.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 1–3.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 572–573.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 26–28.

- ↑ Domagalski, p. 28.

- ↑ Frank, pp. 577–578.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Wright, p. 36.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 40–42.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 45–47.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 49–50, 52–53.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 53–57.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 61–63.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 65–67.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 67–68, 71.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 74–78.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 78, 85–87.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 87–89.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 78–83, 89–90.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 103–108.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 108–109, 112–114, 116–118.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 119–125.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 133–134, 139–145, 150–152.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 152–156, 159–162, 175, 178–179.

- ↑ Domagalski, pp. 102, 179–189, 193–195.

- 1 2 Hanson.

References

- Bonner, Kermit (1996). Final Voyages. Paducah: Turner Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-56311-289-8.

- Cook, Charles O. (1992). The Battle of Cape Esperance: Encounter at Guadalcanal. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-126-4.

- Domagalski, John J. (2012). Sunk in Kula Gulf: The Final Voyage of the USS Helena and the Incredible Story of Her Survivors in World War II. Potomac Books Inc. ISBN 978-1-59797-839-2.

- Frank, Richard B. (1990). Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. Marmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-016561-6.

- Friedman, Norman (1980). "United States of America". In Gardiner, Robert & Chesneau, Roger (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 86–166. ISBN 978-0-87021-913-9.

- Friedman, Norman (1984). U.S. Cruisers: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis: US Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-718-0.

- Hanson, Amy Beth (18 April 2018). "Nearly 75 Years After USS Helena Was Sunk, Its Wreckage Has Been Found". Independent Record. Associated Press. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- Hammel, Eric (1988). Guadalcanal: Decision at Sea: The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, November 13–15, 1942. New York: Pacifica Press. ISBN 978-0-517-56952-8.

- "Helena II (CL-50)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. 25 October 2005. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- Hornfischer, James D. (2011). Neptune's Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-80670-0.

- Kilpatrick, C. W. (1987). The Naval Night Battles of the Solomons. Exposition Press. ISBN 978-0-682-40333-7.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). "The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, 12–15 November 1942". The Struggle for Guadalcanal, August 1942 – February 1943, vol. 5 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-58305-3.

- Naval Historical Division (1959). Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Vol. I. Washington: Naval History Division. OCLC 627492823.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea, 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-119-8.

- Silverstone, Paul (2012). The Navy of World War II, 1922–1947. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-283-60758-2.

- Terzibaschitsch, Stefan (1988). Cruisers of the US Navy 1922–1962. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-974-0.

- "USS Helena, Report of Pearl Harbor Attack". history.navy.mil. Naval History and Heritage Command. 20 February 2018. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- Whitley, M. J. (1995). Cruisers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. London: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 978-1-85409-225-0.

- Wright, Christopher C. (2019). "Answer to Question 1/56". Warship International. Toledo: International Naval Research Organization. LVI (1): 22–46. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Zimm, Alan D. (2011). Attack on Pearl Harbor: Strategy, Combat, Myths, Deceptions. Havertown: Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-61200-010-7.

Further reading

External links

- Photo gallery of USS Helena at NavSource Naval History