| Koli Point action | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theater of World War II | |||||||

75 mm pack howitzers of the 11th U.S. Marine Regiment fire in support of the operation against Japanese forces around Koli Point. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

3,500[1] | 2,500–3,500[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 40 killed[3] | 450+ killed[4] | ||||||

Location within Pacific Ocean  Koli Point action (Solomon Islands) | |||||||

The Koli Point action, during 3–12 November 1942, was an engagement between U.S. Marine Corps and U.S. Army forces and Imperial Japanese Army forces around Koli Point on Guadalcanal during the Guadalcanal campaign. The U.S. forces were under the overall command of Major General Alexander Vandegrift, while the Japanese forces were under the overall command of Lieutenant General Harukichi Hyakutake.

U.S. Marines from the 7th Marine Regiment and U.S. Army soldiers from the 164th Infantry Regiment under the tactical command of William H. Rupertus and Edmund B. Sebree, attacked a concentration of Japanese Army troops, most of whom belonged to the 230th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Toshinari Shōji. Shōji's troops had marched to the Koli Point area after the failed Japanese assaults on U.S. defenses during the Battle for Henderson Field in late October 1942.

In the engagement, the U.S. forces attempted to encircle and destroy Shōji's forces. Although Shōji's unit took heavy casualties, he and most of his men were able to evade the encirclement attempt and escape into the interior of Guadalcanal. As Shōji's troops endeavored to reach Japanese positions in another part of the island, they were pursued and attacked by a battalion-sized patrol of U.S. Marine Raiders.

Background

Guadalcanal campaign

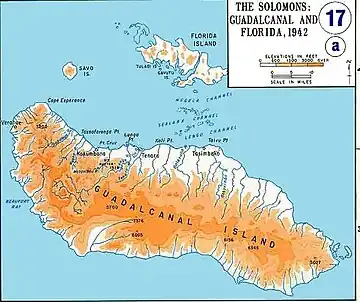

On 7 August 1942, Allied forces (primarily U.S.) landed on Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and Florida Islands in the Solomon Islands. The landings on the islands were meant to deny their use by the Japanese as bases for threatening the supply routes between the U.S. and Australia, and to secure the islands as starting points for a campaign with the eventual goal of isolating the major Japanese base at Rabaul while also supporting the Allied New Guinea campaign. The landings initiated the six-month-long Guadalcanal campaign.[5]

Taking the Japanese by surprise, by nightfall on 8 August the 11,000 Allied troops—under the command of Major General Alexander Vandegrift and mainly consisting of U.S. Marines—had secured Tulagi and nearby small islands as well as an airfield under construction at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal. The airfield was later named Henderson Field by Allied forces. The Allied aircraft that subsequently operated out of the airfield became known as the "Cactus Air Force" (CAF) after the Allied codename for Guadalcanal. To protect the airfield, the U.S. Marines established a perimeter defense around Lunga Point.[6]

In response to the Allied landings on Guadalcanal, the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters assigned the Imperial Japanese Army's 17th Army—a corps-sized command based at Rabaul and under the command of Lieutenant-General Harukichi Hyakutake—with the task of retaking Guadalcanal from Allied forces. Beginning on 19 August, various units of the 17th Army began to arrive on Guadalcanal with the goal of driving Allied forces from the island.[7]

Because of the threat by CAF aircraft based at Henderson Field, the Japanese were unable to use large, slow transport ships to deliver troops and supplies to the island. Instead, the Japanese used warships based at Rabaul and the Shortland Islands to carry their forces to Guadalcanal. The Japanese warships, mainly light cruisers or destroyers from the Eighth Fleet under the command of Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, were usually able to make the round trip down "The Slot" to Guadalcanal and back in a single night, thereby minimizing their exposure to CAF air attack. Delivering the troops in this manner, however, prevented most of the soldiers' heavy equipment and supplies, such as heavy artillery, vehicles, and much food and ammunition, from being carried to Guadalcanal with them. These high-speed warship runs to Guadalcanal occurred throughout the campaign and were later called the "Tokyo Express" by Allied forces and "Rat Transportation" by the Japanese.[8]

The first Japanese attempt to recapture Henderson Field failed when a 917-man force was defeated on 21 August in the Battle of the Tenaru. The next attempt took place from 12 to 14 September, with the 6,000 soldiers under the command of Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi being defeated in the Battle of Edson's Ridge. After their defeat at Edson's Ridge, Kawaguchi and the surviving Japanese troops regrouped west of the Matanikau River.[9]

As the Japanese regrouped, the U.S. forces concentrated on shoring up and strengthening their Lunga defenses. On 18 September, an Allied naval convoy delivered 4,157 men from the U.S. 7th Marine Regiment to Guadalcanal. These reinforcements allowed Vandegrift—beginning on 19 September—to establish an unbroken line of defense completely around the Lunga perimeter.[10]

General Vandegrift and his staff were aware that Kawaguchi's troops had retreated to the area west of the Matanikau and that numerous groups of Japanese stragglers were scattered throughout the area between the Lunga Perimeter and the Matanikau River. Vandegrift therefore decided to conduct a series of small unit operations around the Matanikau Valley.[11]

The first U.S. Marine operation against Japanese forces west of the Matanikau, conducted between 23 and 27 September 1942 by elements of three U.S. Marine battalions, was repulsed by Kawaguchi's troops under Colonel Akinosuke Oka's local command. In the second action, between 6 and 9 October, a larger force of U.S. Marines successfully crossed the Matanikau River, attacked newly landed Japanese forces from the 2nd (Sendai) Infantry Division under the command of generals Masao Maruyama and Yumio Nasu and inflicted heavy casualties on the Japanese 4th Infantry Regiment. The second action forced the Japanese to retreat from their positions east of the Matanikau.[13]

In the meantime, Major General Millard F. Harmon—commander of U.S. Army forces in the South Pacific—convinced Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley—commander of Allied forces in the South Pacific Area—that U.S. Marine forces on Guadalcanal needed to be reinforced immediately if the Allies were to successfully defend the island from the next expected Japanese offensive. Thus on 13 October, a naval convoy delivered the 2,837-strong 164th U.S. Infantry Regiment, a North Dakota Army National Guard formation from the U.S. Army's Americal Division, to Guadalcanal.[14]

Battle for Henderson Field

Between 1 and 17 October, the Japanese delivered 15,000 troops to Guadalcanal, giving Hyakutake 20,000 total troops to employ for his planned offensive. Because of the loss of their positions on the east side of the Matanikau, the Japanese decided an attack on the U.S. defenses along the coast would be prohibitively difficult. Thus, after observation of the American defenses around Lunga Point by his staff officers, Hyakutake decided that the main thrust of his planned attack would be from south of Henderson Field. His 2nd Division (augmented by troops from the 38th Division)—under Lieutenant General Masao Maruyama and comprising 7,000 soldiers in three infantry regiments of three battalions each—was ordered to march through the jungle and attack the American defenses from the south near the east bank of the Lunga River. The 2nd Division was split into three units; the Left Wing Unit under Major General Yumio Nasu containing the 29th Infantry Regiment, the Right Wing Unit under Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi consisting of troops from the 230th Infantry Regiment (from the 38th Infantry Division), and the division reserve led by Maruyama comprising the 16th Infantry Regiment.[15]

On 23 October, Maruyama's forces struggled through the jungle to reach the American lines. Kawaguchi—on his own initiative—began to shift his right wing unit to the east, believing that the American defenses were weaker in that area. Maruyama—through one of his staff officers—ordered Kawaguchi to keep to the original attack plan. When he refused, Kawaguchi was relieved of command and replaced by Colonel Toshinari Shōji, commander of the 230th Infantry Regiment. That evening, after learning that the left and right wing forces were still struggling to reach the American lines, Hyakutake postponed the attack to 19:00 on 24 October. The Americans remained completely unaware of the approach of Maruyama's forces.[16]

Finally, late on October 24 Maruyama's forces reached the U.S. Lunga perimeter. Over two consecutive nights Maruyama's forces conducted numerous, unsuccessful frontal assaults on positions defended by troops of the 1st Battalion, 7th Marines (1/7) under Lieutenant Colonel Chesty Puller and the U.S. Army's 3rd Battalion, 164th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Robert Hall. U.S. Marine and Army rifle, machine gun, mortar, artillery and direct canister fire from 37 mm (1.46 in) anti-tank guns "wrought terrible carnage" on the Japanese.[17] More than 1,500 of Maruyama's troops were killed in the attacks while the Americans lost about 60 killed. Shōji's right wing units did not participate in the attacks, choosing instead to remain in place to cover Nasu's right flank against a possible attack in that area by U.S. forces that never materialized.[18]

At 08:00 on 26 October, Hyakutake called off any further attacks and ordered his forces to retreat. Maruyama's left wing and division reserve survivors were ordered to retreat back to the Matanikau River area while the right wing unit under Shōji was told to head for Koli Point, 13 mi (21 km) east of the Lunga River.[19]

To provide support for the right wing units (now called the Shōji Detachment) marching towards Koli, the Japanese dispatched a Tokyo Express run for the night of 2 November to land 300 fresh troops from a previously uncommitted company of the 230th Infantry Regiment, two 75 mm (2.95 in) mountain guns, provisions, and ammunition at Koli Point. American radio intelligence intercepted Japanese communications concerning this effort and the Marine command on Guadalcanal determined to try to intercept it. With many of the American units currently involved in an operation west of the Matanikau, Vandgrift could spare only one battalion. The 2nd Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment (2/7)—commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Herman H. Hanneken—marched east from Lunga Point at 06:50 on 2 November and reached Koli Point after dark the same day. After crossing the Metapona River at its mouth, Hanneken deployed his troops along 2,000 yd (1,800 m) in the woods facing the beach to await the arrival of the Japanese ships.[20]

Action

Early on the morning of 3 November, the five Japanese destroyers arrived at Koli Point and began to unload their cargoes and troops about 1,000 yd (910 m) east of Hanneken's battalion. Hanneken's force remained concealed and unsuccessfully attempted to contact their headquarters by radio to report the landing. At dawn, after a Japanese patrol discovered the Marines, combat with mortar, machine gun, and small arms fire began. Soon after, the Japanese unlimbered and began to fire the two mountain guns that they had landed during the night. Hanneken was still unable to contact his headquarters to request support; having suffered significant casualties and running low on ammunition, he decided to retreat. Hanneken's battalion withdrew by bounds, recrossing the Metapona, and then the Nalimbiu River 5,000 yd (4,600 m) further west, where Hanneken was finally able to establish contact with his superiors at 14:45 to report his situation.[21]

In addition to Hanneken's report of sizable Japanese forces at Koli Point, Vandegrift's staff also possessed a captured Japanese document that outlined a plan to land the remainder of the 38th Infantry Division at Koli to attack the Marine Lunga defenses from the east. Unaware that the Japanese had abandoned the plan, Vandegrift decided that the threat from Koli Point needed to be dealt with immediately. Thus, he ordered most of the Marine units currently engaged west of the Matanikau to return to Lunga Point. Puller's battalion (1/7) was ordered to prepare to move to Koli Point by boat. The 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the 164th Infantry Regiment (2/164 and 3/164) prepared to march inland to the Nalimbiu River. The 3rd Battalion, 10th Marines began to move its 75 mm pack howitzers across the Ilu river to provide artillery support. Marine Brigadier General William Rupertus was placed in command of the operation.[22]

At the same time that the U.S. forces were mobilizing, Shōji and his troops were beginning to reach Koli Point east of the Metapona River at Gavaga Creek. Late in the day, 31 CAF aircraft attacked Shōji's forces, inflicting about 100 deaths and injuries on the Japanese. Some of the CAF aircraft also mistakenly attacked Hanneken's men, causing several deaths and injuries to the Marines.[23]

At 06:30 on 4 November, the 164th troops began their march towards Koli Point. Around the same time, Rupertus and Puller's battalion landed at Koli Point near the mouth of the Nalimbiu River. Rupertus decided to wait for the army troops to arrive before attacking Shōji's forces. Because of heat, humidity, and difficult terrain the 164th troops did not complete the 7 mi (11 km) march to the Nalimbiu until nightfall. In the meantime, the U.S. Navy cruisers Helena, San Francisco, and destroyer Sterett bombarded Shōji's positions with artillery fire, killing many officers and soldiers from the 9th and 10th Companies, 230th Infantry.[24]

On the morning of 5 November, Rupertus ordered the 164th troops to cross to the east bank of the Nalimbiu and envelop the inland flank of any Japanese forces that might be facing Puller's battalion. The two battalions crossed the river about 3,500 yd (3,200 m) inland and pivoted north to advance along the east bank. The army troops encountered few Japanese but were greatly slowed by difficult terrain, and they stopped short of the coast for the night. That same day, the Japanese troops that had been landed by the warships on 3 November made contact with and joined Shōji's forces.[25]

On 6 November Puller's battalion crossed the Nalimbiu as the 164th troops resumed their march towards the coast. On 7 November, the Marines and army units joined forces at the coast and pushed east to a point about 1 mi (1.6 km) west of the Metapona, where they dug in near the beach because of sightings of a Japanese Express run heading for Guadalcanal that might land reinforcements at Koli that night. The Japanese, however, successfully landed the reinforcements elsewhere on Guadalcanal that night, and these reinforcements were not a factor in the Koli Point action.[26]

Meanwhile, Hyakutake ordered Shōji to abandon his positions at Koli and rejoin Japanese forces at Kokumbona in the Matanikau area. To cover the withdrawal, a sizable portion of Shōji's forces dug-in and prepared to defend positions along Gavaga Creek near the village of Tetere, about 1 mi (1.6 km) east of the Metapona. The two mountain guns landed on 3 November—in combination with mortars—kept up a constant rate of fire on the advancing Americans. On 8 November, Puller's and Hanneken's battalions and the 164th soldiers attempted to surround Shōji's forces by approaching Gavaga overland from the west and landing by boat near Tetere in the east. In action during the day, Puller was wounded several times and was evacuated. Rupertus, who was suffering from dengue fever, relinquished command of the operation to U.S. Army Brigadier General Edmund B. Sebree.[27]

On 9 November, the U.S. troops continued with their attempt to encircle Shōji's forces. On the west of Gavaga Creek, 1/7 and 2/164 extended their positions inland along the creek while 2/7 and other 164th troops took positions on the east side of Shōji's positions. The Americans began to compress the pocket while subjecting it to constant bombardment by artillery, mortars, and aircraft. A gap, however, existed by way of a swampy creek in the southern side of the American lines, which 2/164 was supposed to have closed. Taking advantage of this route, Shōji's men began to escape the pocket.[28]

The Americans closed the gap in their lines on 11 November, but by then Shōji and between 2,000 and 3,000 of his men had escaped into the jungle to the south. On 12 November, Sebree's forces completely overran and killed all the remaining Japanese soldiers left in the pocket. The Americans counted the bodies of 450–475 Japanese dead in the area and captured most of Shōji's heavy weapons and provisions. The American forces suffered 40 killed and 120 wounded in the operation.[29]

Aftermath

As Shōji's forces began their march to rejoin the main body of Japanese forces west of the Matanikau River, the U.S. 2nd Marine Raider Battalion—under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Evans Carlson, which had been guarding an airfield construction effort underway at Aola Bay, 30 mi (48 km) further east from Koli Point—set off in pursuit. Over the next month, with the aid of native scouts, Carlson's Raiders repeatedly attacked trailing elements and stragglers from Shōji's forces, killing almost 500 of them. In addition, lack of food and tropical diseases felled more of Shōji's men. By the time the Japanese reached the Lunga River, about halfway to the Matanikau, only 1,300 men remained with Shōji's main body. Several days later, when Shōji reached the 17th Army positions west of the Matanikau, only 700–800 survivors were still with him. Survivors from Shōji's force later participated in the Battle of Mount Austen, the Galloping Horse, and the Sea Horse in December 1942 and January 1943.[30]

Speaking of the Koli Point action, U.S. Sergeant (later Brigadier General) John E. Stannard, who participated as a member of the 164th Regiment, stated that the battle for Koli Point was "the most complex land operation, other than the original landing, that the Americans had conducted on Guadalcanal up to that time." He added, "The Americans learned once again that offensive operations against the Japanese were much more complicated and difficult than was defeating banzai charges."[31] The Americans later abandoned the attempt to construct an airfield at Aola. Instead, the Aola construction units moved to Koli Point where they successfully built an auxiliary airfield beginning on 3 December 1942.[32]

The next major Japanese reinforcement effort failed during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, undertaken as Shōji and his troops struggled to reach friendly lines near the Matanikau. Although most of Shōji's troops had escaped from Koli Point, the inability of the Japanese to keep their forces on Guadalcanal adequately supplied or reinforced prevented them from contributing effectively to what turned out to be Japan's ultimately unsuccessful effort to hold the island or retake Henderson Field from Allied forces.[33]

Notes

- ↑ Estimate based by summing the number of troops from the four battalions involved, plus additional support troops. A battalion normally consisted of 500–1,000 troops but the U.S. Marine and Army battalions on Guadalcanal had, by this time, been reduced by combat casualties, tropical disease, and operational accidents. This number represents the actual number directly involved in the battle, not the total number of Allied troops on Guadalcanal, which numbered almost 25,000.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 423 says 3,500; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 216, says 2,500. The total number of Japanese troops on Guadalcanal at this time was around 20,000,

- ↑ Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 223

- ↑ Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 223; Miller, Guadalcanal, p. 200.

- ↑ Hogue, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, pp. 235–236.

- ↑ Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 14–15; and Shaw, First Offensive, p. 18.

- ↑ Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 96–99; Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 225; Miller, Guadalcanal: The First Offensive, pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 202, 210–211.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 141–143, 156–158, 228–246, 681.

- ↑ Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 156; and Smith, Bloody Ridge, pp. 198–200.

- ↑ Smith, Bloody Ridge, p. 204; and Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 270.

- ↑ Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 106.

- ↑ Zimmerman, The Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 96–101; Smith, Bloody Ridge, pp. 204–215; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 269–290; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 169–176; and Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, pp. 318–322. The 2nd Infantry was called Sendai because most of its soldiers were from Miyagi Prefecture.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 293–297; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, pp. 147–149; Miller, Guadalcanal: The First Offensive, pp. 140–142; and Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, p. 225.

- ↑ Jersey, Hell's Islands, pp. 272, 297; Shaw, First Offensive, p. 34; and Rottman, Japanese Army, pp. 61–63; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 328–340; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, pp. 329–330; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 186–187. Frank states that Kawaguchi's forces also included what remained of the 3rd Battalion, 124th Infantry Regiment which was originally part of the 35th Infantry Brigade commanded by Kawaguchi during the Battle of Edson's Ridge. Jersey states that it was actually the 2nd Battalion of the 124th along with 1st and 3rd battalions of the 230th Infantry Regiment, parts of the 3rd Independent Trench Mortar Battalion, the 6th Independent Rapid-Fire Gun Battalion, the 9th Independent Rapid-Fire Gun Battalion, and the 20th Independent Mountain Artillery.

- ↑ Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 193; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 346–348; Rottman, Japanese Army, p. 62.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 361–362.

- ↑ Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 336; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 353–362; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 197–204; and Miller, Guadalcanal: The First Offensive, pp. 160–162.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 363–406, 418, 424, 553; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 122–123; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 204; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, pp. 337, 347; Rottman, Japanese Army, p. 63; Miller, Guadalcanal, p. 195.

- ↑ Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 133–134; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 217; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 347; Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 414; Miller, Guadalcanal, pp. 195–196; Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 140; Shaw, First Offensive, pp. 41–42; Jersey, Hell's Islands, p. 297. Jersey states that the troops landed were from the 2nd Company, 230th Infantry commanded by 1st Lt Tamotsu Shinno plus the 6th Battery, 28th Mountain Artillery Regiment with the two guns. The provisions included 650 bales of rice and ten bales of powdered miso.

- ↑ Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 347; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 134–135; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 415–416; Miller, Guadalcanal, pp. 196–197; Hammel, Guadalcanal, pp. 140–141; Shaw, First Offensive, pp. 41–42; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 217; and Jersey, Hell's Islands, p. 297. According to Jersey, the Japanese troops facing Hanneken weren't the only ones landed during the night, but also the 9th Company, 230th Regiment which had previously been stationed at Koli Point to receive and protect the incoming reinforcements.

- ↑ Anderson, Guadalcanal; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 217–219; Miller, Guadalcanal, p. 197; Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 141; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 417–418; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 348; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 135–138.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 419; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 348; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 217–219; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 136–138.

- ↑ Jersey, Hell's Islands, p. 298; Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 142; Miller, Guadalcanal, pp. 197–198; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 348; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 218–219; Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 420; Morison, Struggle for Guadalcanal, p. 226; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Miller, Guadalcanal, p. 198; Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 421; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 348; Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 143; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, p. 138.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 421–422; Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 143; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 348; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 217–219; Miller, Guadalcanal, pp. 198–199. The Express run deposited its troops and provisions at Tassafaronga and Cape Esperance west of Lunga Point.

- ↑ Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 143; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 349; Shaw, First Offensive, p. 42; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, pp. 219 and 223; Miller, Guadalcanal, pp. 198–199; Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 422; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 138–139; and Jersey, Hell's Islands, pp. 298–299.

- ↑ Shaw, First Offensive, p. 42; Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 423; Miller, Guadalcanal, p. 199; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 223; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, pp. 349–350; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 139–141; Jersey, Hell's Islands, p. 305.

- ↑ Jersey, Hell's Islands, p. 305; Miller, Guadalcanal, p. 200; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 223; Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 350; Frank, Guadalcanal, p. 423; Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 144; Shaw, First Offensive, p. 42; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 139–141. Frank states the number of Japanese dead was 450, Jersey states it was 475.

- ↑ Hough, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, p. 350; Shaw, First Offensive, pp. 42–43; Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 423–424; Griffith, Battle for Guadalcanal, p. 246; Miller, Guadalcanal, p. 200; Zimmerman, Guadalcanal Campaign, pp. 141–145; Jersey, p. 361.

- ↑ Jersey, Hell's Islands, p. 299.

- ↑ Miller, Guadalcanal, p. 174.

- ↑ Frank, Guadalcanal, pp. 428–492; Rottman, Japanese Army, p. 64; Dull, Imperial Japanese Navy, pp. 245–69; Hammel, Guadalcanal, p. 144.

References

Books

- Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941–1945. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-097-1.

- Frank, Richard (1990). Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-58875-4.

- Griffith, Samuel B. (1963). The Battle for Guadalcanal. Champaign, Illinois, US: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06891-2.

- Hammel, Eric (2007). Guadalcanal: The U.S. Marines in World War II. St. Paul, Minnesota: Zenith Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-3148-4.

- Jersey, Stanley Coleman (2008). Hell's Islands: The Untold Story of Guadalcanal. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-616-2.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1958). The Struggle for Guadalcanal, August 1942 – February 1943, vol. 5 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-58305-7.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2005). Japanese Army in World War II: The South Pacific and New Guinea, 1942–43. Dr. Duncan Anderson (consultant editor). Oxford and New York: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-870-7.

- Smith, Michael T. (2000). Bloody Ridge: The Battle That Saved Guadalcanal. New York: Pocket. ISBN 0-7434-6321-8.

Web

- Anderson, Charles R. (1993). Guadalcanal. The U.S. Army Campaigns in World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-8. Archived from the original on 2007-12-20. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

- Hough, Frank O.; Ludwig, Verle E.; Shaw, Henry I. Jr. "Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal". History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Retrieved 2006-05-16.

- Miller, John Jr. (1995) [1949]. Guadalcanal: The First Offensive. United States Army in World War II. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 5-3. Archived from the original on 2007-12-25. Retrieved 2006-07-04.

- Shaw, Henry I. (1992). "First Offensive: The Marine Campaign For Guadalcanal". Marines in World War II Commemorative Series. Retrieved 2006-07-25.

- Zimmerman, John L. (1949). "The Guadalcanal Campaign". Marines in World War II Historical Monograph. Retrieved 2006-07-04.

External links

Media related to Koli Point action at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Koli Point action at Wikimedia Commons