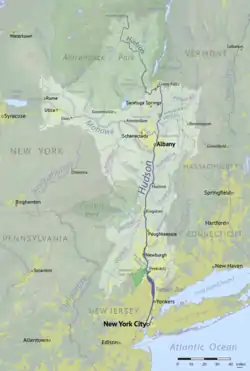

| Hudson River | |

|---|---|

The Hudson River Watershed, including the Hudson and Mohawk rivers | |

| |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New York, New Jersey |

| City | See Populated places on the Hudson River |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Henderson Lake (New York) (See Sources) |

| • location | Adirondack Mountains, New York, United States |

| • coordinates | 44°05′29″N 74°03′33″W / 44.09139°N 74.05917°W[1] |

| • elevation | 1,770[2] ft (540 m) |

| Mouth | New York Harbor |

• location | Jersey City, New Jersey and Lower Manhattan, New York, United States |

• coordinates | 40°41′48″N 74°01′42″W / 40.69667°N 74.02833°W[1] |

• elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Length | 315 mi (507 km) |

| Basin size | 14,000 sq mi (36,000 km2) |

| Depth | |

| • average | 30 ft (9.1 m) (extent south of Troy) |

| • maximum | 202 ft (62 m) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Lower New York Bay[3] |

| • average | 21,900 cu ft/s (620 m3/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Green Island[4] |

| • average | 17,400 cu ft/s (490 m3/s) |

| • minimum | 882 cu ft/s (25.0 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 215,000 cu ft/s (6,100 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Boreas River, Schroon River, Batten Kill, Hoosic River, Kinderhook Creek, Roeliff Jansen Kill, Wappinger Creek, Croton River |

| • right | Cedar River, Indian River, Sacandaga River, Mohawk River, Normans Kill, Catskill Creek, Esopus Creek, Rondout Creek, Wallkill River |

| Waterfalls | Ord Falls, Spier Falls, Glens Falls, Bakers Falls |

The Hudson River is a 315-mile (507 km) river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York, United States. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York at Henderson Lake in the town of Newcomb, and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between New York City and Jersey City, eventually draining into the Atlantic Ocean at Upper New York Bay. The river serves as a physical boundary between the states of New Jersey and New York at its southern end. Farther north, it marks local boundaries between several New York counties. The lower half of the river is a tidal estuary, deeper than the body of water into which it flows, occupying the Hudson Fjord, an inlet that formed during the most recent period of North American glaciation, estimated at 26,000 to 13,300 years ago. Even as far north as the city of Troy, the flow of the river changes direction with the tides.

The Hudson River runs through the Munsee, Lenape, Mohican, Mohawk, and Haudenosaunee homelands. Prior to European exploration, the river was known as the Mahicannittuk by the Mohicans, Ka'nón:no by the Mohawks, and Muhheakantuck by the Lenape. The river was subsequently named after Henry Hudson, an Englishman sailing for the Dutch East India Company who explored it in 1609, and after whom Hudson Bay in Canada is also named. It had previously been observed by Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano sailing for King Francis I of France in 1524, as he became the first European known to have entered the Upper New York Bay, but he considered the river to be an estuary. The Dutch called the river the North River, and they called the present-day Delaware River the South River, which formed the spine of the Dutch colony of New Netherland. Settlements of the colony clustered around the Hudson, and its strategic importance as the gateway to the American interior led to years of competition between the English and the Dutch over control of the river and colony.

During the 18th century, the river valley and its inhabitants were the subject and inspiration of Washington Irving, the first internationally acclaimed American author. In the nineteenth century, the area inspired the Hudson River School of landscape painting, an American pastoral style, as well as the concepts of environmentalism and wilderness. The Hudson River was also the eastern outlet for the Erie Canal, which, when completed in 1825, became an important transportation artery for the early 19th century United States.

Pollution in the Hudson River increased in the 20th century, more acutely by mid-century, particularly with industrial contamination from polychlorinated biphenyls, also known by their acronym PCBs. Pollution control regulations, enforcement actions and restoration projects initiated in the latter 20th century have begun to improve water quality, and restoration work has continued in the 21st century.[5][6]

| Hamilton |

| Essex |

| Warren |

| Washington |

| Saratoga |

| Albany |

| Rensselaer |

| Greene |

| Columbia |

| Ulster |

| Dutchess |

| Putnam |

| Orange |

| Rockland |

| Westchester |

| Bronx |

| Bergen, NJ |

| Hudson, NJ |

| New York |

| Source:[7] |

Names

The river was called Ka’nón:no[8] or Ca-ho-ha-ta-te-a ("the river")[9] by the Haudenosaunee, and it was known as Muh-he-kun-ne-tuk ("river that flows two ways" or "waters that are never still"[10]) or Mahicannittuk[11] by the Mohican nation who formerly inhabited both banks of the lower portion of the river. The meaning of the Mohican name comes from the river's long tidal range. The Delaware Tribe of Indians (Bartlesville, Oklahoma) considers the closely related Mohicans to be a part of the Lenape people,[12] and so the Lenape also claim the Hudson as part of their ancestral territory, also calling it Muhheakantuck.[13]

The first known European name for the river was the Rio San Antonio as named by the Portuguese explorer in Spain's employ, Estêvão Gomes, who explored the Mid-Atlantic coast in 1525.[14] Another early name for the Hudson used by the Dutch was Rio de Montaigne.[15] Later, they generally termed it the Noortrivier, or "North River", the Delaware River being known as the Zuidrivier, or "South River". Other occasional names for the Hudson included Manhattes rieviere "Manhattan River", Groote Rivier "Great River", and de grootte Mouritse reviere, or "the Great Maurits River" (after Maurice, Prince of Orange).[16]

The translated name North River was used in the New York metropolitan area up until the early 1900s, with limited use continuing into the present day.[17] The term persists in radio communication among commercial shipping traffic, especially below the Tappan Zee.[18] The term also continues to be used in names of facilities in the river's southern portion, such as the North River piers, North River Tunnels, and the North River Wastewater Treatment Plant. It is believed that the first use of the name Hudson River in a map was in a map created by the cartographer John Carwitham in 1740.[19]

In 1939, the magazine Life described the river as "America's Rhine", comparing it to the 40-mile (64 km) stretch of the Rhine in Central and Western Europe.[20]

The tidal Hudson is unusually straight for a river, and the earliest colonial Dutch charts of the Hudson River designated the narrow, meandering stretches as racks, or reaches.[21][22] These names included the four "lower reaches" through the Hudson Highlands (Seylmakers rack, Cocks rack, Hoogh rack, and Vosserack) plus the four "upper reaches" from Inbocht Bay to Kinderhook (Backers rack, Jan Pleysiers rack, Klevers rack, and Harts rack). A ninth reach was described as "the long reach" by the Englishman Robert Juet and designated as the Langerack by the Dutch.[23] An embellished (and partly erroneous) list of "The Old Reaches" was published in a tourist guidebook for steamboat passengers in the nineteenth century.[24][25]

Course

Sources

The source of the Hudson River is Henderson Lake (New York) in the Adirondack Park at an elevation of 4,322 feet (1,317 m).[26][27] Popular culture and convention, however, more often cite the photogenic Lake Tear of the Clouds as the source.[28] Originating from this lake, the river is named Feldspar Brook until its confluence with the Opalescent River, and then is named the Opalescent River until the river reaches Calamity Brook, flowing south into the eastern outlet of Henderson Lake. From that point on, the stream is cartographically known as the Hudson River.[29][30][31] The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) uses this cartographical definition.[7]

Although Lake Tear of Clouds is traditionally considered as the source, the longest source of the Hudson River as shown on the most detailed USGS maps is the Opalescent River on the west slopes of Little Marcy Mountain,[32][33] originating two miles north of Lake Tear of the Clouds,[33][34] several miles, past the Flowed Lands, to the Hudson River [35] and a mile longer than "Feldspar Brook", which flows out of that lake in the Adirondack Mountains.[28]

Upper Hudson River

Using river names as seen on maps, Indian Pass Brook flows into Henderson Lake. The outlet of Henderson Lake is most commonly referred to as the official start of the Hudson River, as it flows east and meets the southwest flowing Calamity Brook. The confluence of the two rivers however is where most maps begin to use the Hudson River name on a cartographical basis. South of the outlet of Sanford Lake, the Opalescent River flows into the Hudson.[2]

The Hudson then flows south, taking in Beaver Brook and the outlet of Lake Harris. After its confluence with the Indian River, the Hudson forms the boundary between Essex and Hamilton counties. The Hudson flows entirely into Warren County in the hamlet of North River, and takes in the Schroon River at Warrensburg. Further south, the river forms the boundary between Warren and Saratoga Counties. The river then takes in the Sacandaga River from the Great Sacandaga Lake.[31]

Shortly thereafter, the river leaves the Adirondack Park, flows under Interstate 87, and through Glens Falls, just south of Lake George although receiving no streamflow from the lake. It next goes through Hudson Falls. At this point the river forms the boundary between Washington and Saratoga Counties.[31] Here the river has an elevation of 200 feet (61 m).[26] Just south in Fort Edward, the river reaches its confluence with the Champlain Canal,[31] which historically provided boat traffic between New York City and Montreal and the rest of Eastern Canada via the Hudson, Lake Champlain and the Saint Lawrence Seaway.[36]

Further south the Hudson takes in water from the Batten Kill River and Fish Creek near Schuylerville. The river then forms the boundary between Saratoga and Rensselaer counties. The river then enters the heart of the Capital District. It takes in water from the Hoosic River, which extends into Massachusetts. Shortly thereafter the river has its confluence with the Mohawk River, the largest tributary of the Hudson River, in Waterford.[26][31] The river then reaches the Federal Dam in Troy, marking an impoundment of the river.[31] At an elevation of 2 feet (0.61 m), the bottom of the dam marks the beginning of the tidal influence in the Hudson as well as the beginning of the lower Hudson River.[26]

Lower Hudson River

South of the Federal Dam, the Hudson River begins to widen considerably. The river enters the Hudson Valley, flowing along the west bank of Albany and the east bank of Rensselaer. Interstate 90 crosses the Hudson into Albany at this point in the river. The Hudson then leaves the Capital District, forming the boundary between Greene and Columbia Counties. It then meets its confluence with Schodack Creek, widening considerably at this point. After flowing by Hudson, the river forms the boundary between Ulster and Columbia Counties and Ulster and Dutchess Counties, passing Germantown and Kingston.[37]

The Delaware and Hudson Canal meets the river at this point. The river then flows by Hyde Park, former residence of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and alongside the city of Poughkeepsie, flowing under the Walkway over the Hudson and the Mid-Hudson Bridge. Afterwards, the Hudson passes Wappingers Falls and takes in Wappinger Creek. The river then forms the boundary between Orange and Dutchess Counties. It flows between Newburgh and Beacon and under the Newburgh Beacon Bridge, taking in the Fishkill Creek.[37]

In this area, between Gee's Point at the US Military Academy and Constitution Island, an area known as "World's End" marks the deepest part of the Hudson, at 202 feet (62 m).[37] Shortly thereafter, the river enters the Hudson Highlands between Putnam and Orange Counties, flowing between mountains such as Storm King Mountain, Breakneck Ridge, and Bear Mountain. The river narrows considerably here before flowing under the Bear Mountain Bridge, which connects Westchester and Rockland Counties.[31]

Afterward, leaving the Hudson Highlands, the river enters Haverstraw Bay, the widest point of the river at 3.5 miles (5.6 km) wide.[26] Shortly thereafter, the river forms the Tappan Zee and flows under the Tappan Zee Bridge, which carries the New York State Thruway between Tarrytown and Nyack in Westchester and Rockland Counties respectively. At the state line with New Jersey the west bank of the Hudson enters Bergen County. The Palisades are large, rocky cliffs along the west bank of the river; also known as Bergen Hill at their lower end in Hudson County.[31]

Further south the east bank of the river becomes Yonkers and then the Riverdale neighborhood of the Bronx in New York City. South of the confluence of the Hudson and Spuyten Duyvil Creek, the east bank of the river becomes Manhattan.[31] The river is sometimes still called the North River at this point. The George Washington Bridge crosses the river between Fort Lee and the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan.[38]

The Lincoln Tunnel and the Holland Tunnel also cross under the river between Manhattan and New Jersey. South of the Battery, the river proper ends, meeting the East River to form Upper New York Bay, also known as New York Harbor. Its outflow continues through the Narrows between Brooklyn and Staten Island, under the Verrazzano Bridge, and into Lower New York Bay and the Atlantic Ocean.[31]

Geography and watershed

The lower Hudson is actually a tidal estuary, with tidal influence extending as far as the Federal Dam in Troy. There are about two high tides and two low tides per day. As the tide rises, the tidal current moves northward, taking enough time that part of the river can be at high tide while another part can be at the bottom of its low tide.[39]

Strong tides make parts of New York Harbor difficult and dangerous to navigate. During the winter, ice floes may drift south or north, depending upon the tides. The Mahican name of the river represents its partially estuarine nature: muh-he-kun-ne-tuk means "the river that flows both ways."[40] Due to tidal influence from the ocean extending to Troy, NY,[39] freshwater discharge is only about 17,400 cubic feet (490 m3) per second on average.[4] The mean fresh water discharge at the river's mouth in New York is approximately 21,900 cubic feet (620 m3) per second.[3]

The Hudson River is 315 miles (507 km) long, with depths of 30 feet (9.1 m) for the stretch south of the Federal Dam, dredged to maintain the river as a shipping route. Some sections there are around 160 feet deep,[39] and the deepest part of the Hudson, known as "World's End" (between the US Military Academy and Constitution Island) has a depth of 202 feet (62 m).[37]

The Hudson and its tributaries, notably the Mohawk River, drain an area of 13,000 square miles (34,000 km2), the Hudson River Watershed. It covers much of New York, as well as parts of Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Vermont.[39]

Parts of the Hudson River form coves, such as Weehawken Cove in the towns of Hoboken and Weehawken in New Jersey.[41]

The City of Poughkeepsie and several adjacent communities in the mid-Hudson valley, totalling about 100,000 people, rely on the river for their drinking water.[42]

Salinity

New York Harbor, between the Narrows and the George Washington Bridge, has a mix of fresh and ocean water, mixed by wind and tides to create an increasing gradient of salinity from the river's top to its bottom. This varies with season, weather, variation of water circulation, and other factors; snowmelt at winter's end increases the freshwater flow downstream.[39]

The salt line of the river varies from the north in Poughkeepsie to the south at Battery Park in New York City, though it usually lies near Newburgh.[43]: 11

Geology

The Hudson is sometimes called, in geological terms, a drowned river. The rising sea levels after the retreat of the Wisconsin glaciation, the most recent ice age, have resulted in a marine incursion that drowned the coastal plain and brought salt water well above the mouth of the river. The deeply eroded old riverbed beyond the current shoreline, Hudson Canyon, is a rich fishing area. The former riverbed is clearly delineated beneath the waters of the Atlantic Ocean, extending to the edge of the continental shelf.[44] As a result of the glaciation and the rising sea levels, the lower half of the river is now a tidal estuary that occupies the Hudson Fjord. The fjord is estimated to have formed between 26,000 and 13,300 years ago.[45]

Along the river, the Palisades are of metamorphic basalt, or diabases, the Highlands are primarily granite and gneiss with intrusions, and from Beacon to Albany, shales and limestones, or mainly sedimentary rock.[43]: 13

The Narrows were most likely formed about 6,000 years ago at the end of the last ice age. Previously, Staten Island and Long Island were connected, preventing the Hudson River from terminating via the Narrows. At that time, the Hudson River emptied into the Atlantic Ocean through a more westerly course through parts of present-day northern New Jersey, along the eastern side of the Watchung Mountains to Bound Brook, New Jersey and then on into the Atlantic Ocean via Raritan Bay. A buildup of water in the Upper New York Bay eventually allowed the Hudson River to break through previous land mass that was connecting Staten Island and Brooklyn to form the Narrows as it exists today. This allowed the Hudson River to find a shorter route to the Atlantic Ocean via its present course between New Jersey and New York City.[46]

Suspended sediments, mainly consisting of clays eroded from glacial deposits and organic particles, can be found in abundance in the river. The Hudson has a relatively short history of erosion, so it does not have a large depositional plain near its mouth. This lack of significant deposits near the river mouth differs from most other American estuaries. Around New York Harbor, sediment also flows into the estuary from the ocean when the current is flowing north.[39]

History

Pre-Columbian era

The area around Hudson River was inhabited by indigenous peoples ages before Europeans arrived. The Lenape, Wappinger, and Mahican branches of the Algonquians lived along the river,[47] mostly in peace with the other groups.[47][48] The Algonquians in the region mainly lived in small clans and villages throughout the area. One major settlement was called Navish, which was located at Croton Point, overlooking the Hudson River. Other settlements were located in various locations throughout the Hudson Highlands. Many villagers lived in various types of houses, which the Algonquians called wigwams, though large families often lived in longhouses that could be a hundred feet long.[48]

At the associated villages, they grew corn, beans, and squash. They also gathered other types of plant foods, such as hickory nuts and many other wild fruits and tubers. In addition to agriculture, the Algonquians also fished in the Hudson River, focusing on various species of freshwater fish, as well as various variations of striped bass, American eels, sturgeon, herring, and shad. Oyster beds were also common on the river floor, which provided an extra source of nutrition. Land hunting consisted of turkey, deer, bear, and other animals.[48]

The lower Hudson River was inhabited by the Lenape,[48] while further north, the Wappingers lived from Manhattan Island up to Poughkeepsie. They traded with both the Lenape to the south and the Mahicans to the north.[47] The Mahicans lived in the northern part of the valley from present-day Kingston to Lake Champlain,[48] with their capital located near present-day Albany.[47]

Exploration and colonization

John Cabot is credited for the Old World's discovery of continental North America, with his journey in 1497 along the continent's coast. In 1524, Florentine explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano sailed north along the Atlantic seaboard and into New York Harbor,[14] however he left the harbor shortly thereafter, without navigating into the Hudson River.[49] In 1598, Dutch men employed by the Greenland Company wintered in New York Bay.[14]

In 1609 the Dutch East India Company financed English navigator Henry Hudson in his search for the Northeast Passage, but thwarted by sea ice in that direction, he sailed westward across the Atlantic in pursuit of a Northwest Passage.[50] During the search, Hudson sailed up the river that would later be named after him. He then sailed upriver to a point near Stuyvesant (Old Kinderhook), and the ship’s boat with five members ventured to the vicinity of present-day Albany, reaching an end to navigation.[51][52]

The Dutch subsequently began to colonize the region, establishing the colony of New Netherland, including three major fur-trading outposts: New Amsterdam, Wiltwyck, and Fort Orange.[53][54] New Amsterdam was founded at the mouth of the Hudson River, and would later become known as New York City. Wiltwyck was founded roughly halfway up the Hudson River, and would later become Kingston. Fort Orange was founded on the river north of Wiltwyck, and later became known as Albany.[53]

The Dutch West India Company operated a monopoly on the region for roughly twenty years before other businessmen were allowed to set up their own ventures in the colony.[53] In 1647, Director-General Peter Stuyvesant took over management of the colony, and surrendered it in 1664 to the British, who had invaded the largely-defenseless New Amsterdam.[53][55] New Amsterdam and the colony of New Netherland were renamed New York, after the Duke of York.[55]

Under British colonial rule, the Hudson Valley became an agricultural hub. Manors were developed on the east side of the river, and the west side contained many smaller and independent farms.[56] In 1754, the Albany Plan of Union was created at Albany City Hall on the Hudson.[57][58] The plan allowed the colonies to treaty with the Iroquois and provided a framework for the Continental Congress.[59][60]

American Revolution

During the American Revolutionary War, the British realized that the river's proximity to Lake George and Lake Champlain would allow their navy to control the water route from Montreal to New York City.[61] British general John Burgoyne planned the Saratoga campaign, to control the river and therefore cut off the patriot hub of New England (to the river's east) from the South and Mid-Atlantic regions to the river's west. The action would allow the British to focus on rallying the support of loyalists in the southerly states.[62] As a result, numerous battles were fought along the river and in nearby waterways. These include the Battle of Long Island, in August 1776[63] and the Battle of Harlem Heights the following month.[64] Later that year, the British and Continental Armies were involved in skirmishes and battles in rivertowns of the Hudson in Westchester County, culminating in the Battle of White Plains.[65]

Also in late 1776, New England militias fortified the river's choke point known as the Hudson Highlands, which included building Fort Clinton and Fort Montgomery on either side of the Hudson and a metal chain between the two. In 1777, Washington expected the British would attempt to control the Hudson River, however they instead conquered Philadelphia, and left a smaller force in New York City, with permission to strike the Hudson Valley at any time. The British attacked on October 5, 1777, in the Battle of Forts Clinton and Montgomery by sailing up the Hudson River, looting the village of Peekskill and capturing the two forts.[66] In 1778, the Continentals constructed the Great West Point Chain in order to prevent another British fleet from sailing up the Hudson.[67]

Hudson River School

Hudson River School paintings reflect the themes of discovery, exploration, and settlement in America in the mid-19th century.[68] The detailed and idealized paintings also typically depict a pastoral setting. The works often juxtapose peaceful agriculture and the remaining wilderness, which was fast disappearing from the Hudson Valley just as it was coming to be appreciated for its qualities of ruggedness and sublimity.[69] The school characterizes the artistic body, its New York location, its landscape subject matter, and often its subject, the Hudson River.[70]

In general, Hudson River School artists believed that nature in the form of the American landscape was an ineffable manifestation of God,[71] though the artists varied in the depth of their religious conviction.[72] Their reverence for America's natural beauty was shared with contemporary American writers such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.[73] The artist Thomas Cole is generally acknowledged as the founder of the Hudson River School,[74] his work first being reviewed in 1825,[75] while painters Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt were the most successful painters of the school.[70]

19th century

.jpg.webp)

At the beginning of the 19th century, transportation from the US east coast into the mainland was difficult. Ships were the fastest vehicles at the time, as trains were still being developed and automobiles were roughly a century away. In order to facilitate shipping throughout the country's interior, numerous canals were constructed between internal bodies of water in the 1800s.[76][77] One of the most significant canals of this era was the Erie Canal. The canal was built to link the Midwest to the Port of New York, a significant seaport during that time, by way of the Great Lakes, the canal, the Mohawk River, and the Hudson River.[77]

The completion of the canal enhanced the development of the American West, allowing settlers to travel west, send goods to markets in frontier cities, and export goods via the Hudson River and New York City. The completion of the canal made New York City one of the most vital ports in the nation, surpassing the Port of Philadelphia and ports in Massachusetts.[77][78][79] After the completion of the Erie Canal, smaller canals were built to connect it with the new system. The Champlain Canal was built to connect the Hudson River near Troy to the southern end of Lake Champlain. This canal allowed boaters to travel from the St. Lawrence Seaway, and then British cities such as Montreal to the Hudson River and New York City.[79]

Another major canal was the Oswego Canal, which connected the Erie Canal to Oswego and Lake Ontario, and could be used to bypass Niagara Falls.[79] The Cayuga-Seneca Canal connected the Erie Canal to Cayuga Lake and Seneca Lake.[79] Farther south, the Delaware and Hudson Canal was built between the Delaware River at Honesdale, Pennsylvania, and the Hudson River at Kingston, New York. This canal enabled the transportation of coal, and later other goods as well, between the Delaware and Hudson River watersheds.[80] The combination of these canals made the Hudson River one of the most vital waterways for trade in the nation.[79]

During the Industrial Revolution, the Hudson River became a major location for production, especially around Albany and Troy. The river allowed for fast and easy transport of goods from the interior of the Northeast to the coast. Hundreds of factories were built around the Hudson, in towns including Poughkeepise, Newburgh, Kingston, and Hudson. The North Tarrytown Assembly (later owned by General Motors), on the river in Sleepy Hollow, was a large and notable example. The River links to the Erie Canal and Great Lakes, allowing manufacturing in the Midwest, including automobiles in Detroit, to use the river for transport.[81]: 71–2 With industrialization came new technologies for transport, including steamboats for faster transport. In 1807, the North River Steamboat (later known as Clermont), became the first commercially successful steamboat. It carried passengers between New York City and Albany along the Hudson River.[82]

The Hudson River valley also proved to be a good area for railroads. The Hudson River Railroad was established in 1849 on the east side of the river as a way to bring passengers from New York City to Albany. The line was built as an alternative to the New York and Harlem Railroad for travel to Albany, and as a way to ease the concerns of cities along the river. The railroad was also used for commuting to New York City.[83] Further north, the Livingston Avenue Bridge was opened in 1866 as a way to connect the Hudson River Railroad with the New York Central Railroad, which goes west to Buffalo.[84][85] Smaller railroads existed north of this point.[86] On the west side of the Hudson River, the West Shore Railroad opened to run passenger service from Weehawken, New Jersey to Albany, and then Buffalo.[87] In 1889, the Poughkeepsie Railroad Bridge opened for rail service between Poughkeepsie and the west side of the river.[88]

20th and 21st centuries

Starting in the 20th century, the technological requirements needed to build large crossings across the river were met. This was especially important by New York City, as the river is fairly wide at that point. In 1927, the Holland Tunnel opened between New Jersey and Lower Manhattan. The tunnel was the longest underwater tunnel in the world at the time, and used an advanced system to ventilate the tunnels and prevent the build-up of carbon monoxide.[89][90] The original upper level of the George Washington Bridge and the first tube of the Lincoln Tunnel followed in the 1930s. Both crossings were later expanded to accommodate extra traffic: the Lincoln Tunnel in the 1940s and 1950s, and the George Washington Bridge in the 1960s.[91] In 1955, the original Tappan Zee Bridge was built over one of the widest parts of the river, from Tarrytown to Nyack.[92][93][94]

The late 20th century saw a decline in industrial production in the Hudson Valley. In 1993, IBM closed two of its plants, in East Fishkill and Kingston, due to the company's loss of $16 billion over the previous three years. The plant in East Fishkill had 16,300 workers at its peak in 1984, and had opened in 1941 originally as part of the war effort.[95] In 1996, the North Tarrytown plant of General Motors (GM) closed.[96] In response to the plant closures, towns throughout the region sought to make the region attractive for technology companies. IBM maintained a mainframe unit at its Poughkeepsie plant, and newer housing and office developments were built near there as well. Commuting from Poughkeepsie to New York City also increased.[95] Developers also looked to build on the property of the old GM plant.[96]

_after_crashing_into_the_Hudson_River_(crop_2).jpg.webp)

Around the time of the last factories' closing, environmental efforts to clean up the river progressed. For example, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) ordered General Electric (GE), which had polluted a 200-mile stretch of the river, to remove PCBs from the site of its old factory in Hudson Falls, as well as to remove millions of cubic yards of contaminated sediment from the river bottom. EPA's cleanup order was issued pursuant to the agency's designation of the polluted segment of the river as a Superfund site.[6] Other conservation efforts also occurred, such as when Christopher Swain became the first person to swim all 315 miles of the Hudson River in support of cleaning it up.[97]

In conjunction with conservation efforts, the Hudson River region has seen an economic revitalization, especially in favor of green development. In 2009, the High Line was opened in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan. This linear park has views of the river throughout its length.[98] Also in 2009, the original Poughkeepsie railroad bridge, since abandoned, was converted into the Walkway Over the Hudson, a pedestrian park over the river.[88] Emblematic of the increase in green development in the region, waterfront parks in cities like Kingston, Poughkeepsie, and Beacon were built, and several festivals are held annually.[99]

Landmarks

.jpg.webp)

Numerous places have been constructed along the Hudson that have since become landmarks. Following the river from its source to mouth, there is the Hudson River Islands State Park in Greene and Columbia counties, and in Dutchess County, there is Bard College, Staatsburgh, the Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site, Franklin D. Roosevelt's home and presidential library, and the main campus of the Culinary Institute of America, Marist College, the Walkway over the Hudson, Bannerman's Castle, and Hudson Highlands State Park. South of that in Orange County is the United States Military Academy. In Westchester lies Indian Point Energy Center, Croton Point Park, and Sing Sing Correctional Facility.

In New Jersey is Stevens Institute of Technology and Liberty State Park. In Manhattan is Fort Tryon Park with the Cloisters, and the World Trade Center. Ellis Island, partially belonging to both the states of New Jersey and New York, is located just south of the river's mouth in New York Harbor. The Statue of Liberty, located on Liberty Island, is located a bit further south of there.[100]

Landmark status and protection

A 30-mile (48 km) stretch on the east bank of the Hudson has been designated the Hudson River Historic District, a National Historic Landmark.[101] The Palisades Interstate Park Commission protects the Palisades on the west bank of the river. The Hudson River was designated as an American Heritage River in 1997.[102] The Hudson River estuary system is part of the National Estuarine Research Reserve System as the Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve.[103]

Transportation and crossings

The Hudson River is navigable by large steamers up to Troy, and by ocean-faring vessels to the Port of Albany.[43]: 11 The original Erie Canal, opened in 1825 to connect the Hudson with Lake Erie, emptied into the Hudson at the Albany Basin, just 3 miles (4.8 km) south of the Federal Dam in Troy (at mile 134). The canal enabled shipping between cities on the Great Lakes and Europe via the Atlantic Ocean.[44] The New York State Canal System, the successor to the Erie Canal, runs into the Hudson River north of Troy.[104] It also uses the Federal Dam as a lock.[105]

Along the east side of the river runs the Metro-North Railroad's Hudson Line, from Manhattan to Poughkeepsie.[106] The tracks continue north of Poughkeepsie as Amtrak trains run further north to Albany.[106] On the west side of the river, CSX Transportation operates a freight rail line between North Bergen Yard in North Bergen, New Jersey and Selkirk Yard in Selkirk, New York.[107][108][109]

The Hudson is crossed at numerous points by bridges, tunnels, and ferries. The width of the Lower Hudson River required major feats of engineering to cross; the results are today visible in the George Washington Bridge and the 1955 Tappan Zee Bridge (replaced by the New Tappan Zee Bridge) as well as the Lincoln and Holland Tunnels and the PATH and Pennsylvania Railroad tubes. The George Washington Bridge, which carries multiple highways, connects Fort Lee, New Jersey to the Washington Heights neighborhood of Upper Manhattan, and is the world's busiest motor vehicle bridge.[38]

The new Tappan Zee Bridge is the longest in New York, although the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge has a larger main span. The Troy Union Bridge between Waterford and Troy was the first bridge over the Hudson; built in 1804 and destroyed in 1909;[110] its replacement, the Troy–Waterford Bridge, was built in 1909.[111] The Rensselaer and Saratoga Railroad was chartered in 1832 and opened in 1835,[112] including the Green Island Bridge,[113] the second bridge over the Hudson south of the Federal Dam.[114]

The Hudson River Day Line offered passenger service on steamboats from New York City to Albany from 1863 until 1962 when it was purchased by Circle Line Sightseeing Cruises.[115][116][117]

Pollution

The Hudson River's sediments contain a significant array of pollutants, accumulated over decades from industrial waste discharges, sewage treatment plants, and urban runoff. Water quality in the river has greatly improved since implementation of the 1972 Clean Water Act (CWA). A 2020 report on the health of the river states that "Water quality in the Hudson River Estuary has improved dramatically since 1972 and has remained largely stable in recent years." Ecological health trends, such as in tributaries and wetlands, are varied in condition. The concentrations of toxic pollutants in fish and crabs are lower compared to measurements taken in previous decades, but fishing restrictions and health warnings remain in effect.[5]: 5

The most significant pollution of the Hudson River was contamination of the river by General Electric (GE) with polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) between 1947 and 1977. These chemicals caused a range of harmful effects to wildlife and people who ate fish from the river.[6][118] Other kinds of pollution, including mercury contamination and discharges of partially treated sewage, have also caused ecological problems in the river.[119][120]

In response to the widespread contamination of the river, activists protested in various ways. A group of fishermen formed an organization in 1966 that would later become Riverkeeper, the first member of the Waterkeeper Alliance.[121] Musician Pete Seeger founded the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater and the Clearwater Festival to draw attention to the problem.[122]

Environmental activism in New York and across the country, and increased attention from members of Congress led to passage of the CWA in 1972.[123][124] Extensive remediation actions on the river began in the 1970s with the issuance and enforcement of CWA wastewater discharge permits and consequent control or reduction of discharges from industrial facilities and municipal sewage treatment plants.[125]

In 1984, EPA declared a 200-mile (320 km) stretch of the river, from Hudson Falls to New York City, as a Superfund site requiring cleanup, one of the largest such site designations in the country.[6] Sediment removal operations by GE, pursuant to the Superfund orders, have continued into the 21st century.[125]

Flora and fauna

Plankton

Zooplankton are abundant throughout both fresh and saltwater portions of the river, and provide a crucial food source for larval and juvenile fish.[39]

Invertebrates

The benthic zone has species capable of living in soft bottom habitats. Within freshwater regions, there are animal species including larvae of chironomid flies, oligochaete worms, predatory fly larvae, and amphipods. In saline regions, there are abundant polychaete annelids, amphipods, and some mollusks such as clams. These species burrow in the sediment and accelerate the breakdown of organic matter. Atlantic blue crabs are among the larger invertebrates, at the northern limit of their range.[39]

The entire Hudson was once far more populated with native suspension-feeding bivalves. Freshwater mussels were common in the river's limnetic zone, but populations have been decreasing for decades, probably from altered habitats and the invasive zebra mussel. Oyster beds were once pervasive in the saltwater portion, but are now reduced through pollution and exploitation.[39]

Fish

About 220 species of fish, including 173 native species, currently are found in the Hudson River.[126] Commercial fishing was once prominent in the river, although most were shut down in 1976 due to pollution; few survive today. American shad are the only finfish harvested for profit, though in limited numbers.[39]

Species include striped bass, the most important game fish in the Hudson. Estimates of the striped bass population in the Hudson range to nearly 100 million fish.[127][128] American eels also live in the river before reaching breeding age; for much of this stage they are known as glass eels because of the transparency of their bodies. The fish are the only catadromous species in the Hudson's estuary.[129]

The Atlantic tomcod is a unique species that adapted resistance to the toxic effects of the PCBs polluting the river. Scientists identified the genetic mutation that conferred the resistance, and found that the mutated form was present in 99 percent of the tomcods in the river, compared to fewer than 10 percent of the tomcods from other waters.[129][130] The hogchoker flatfish have been historically abundant in the river, where farmers would use them for inexpensive livestock feed, giving the fish its name.[129] Other unusual fish found in the river include the northern pipefish, the lined seahorse, and the northern puffer.[129]

The Atlantic sturgeon, a species about 120 million years old, enter the estuary during their annual migrations. The fish grow to a considerable size, up to 15 feet (4.6 m) and 800 pounds (360 kg).[129] The fish are the symbol of the Hudson River Estuary. Their smoked flesh was commonly eaten in the river valley since 1779, and it was sometimes known as "Albany beef". The city of Albany was called "Sturgeondom" or "Sturgeontown" in the 1850s and 1860s, with its residents known as "Sturgeonites". The "Sturgeondom" name lost popularity around 1900.[131] The fish have been off limits from fishing since 1998. The river's population of shortnose sturgeon have quadrupled since the 1970s, and are also off limits to all fishing as they are a federally endangered species.[39]

Lined seahorse or northern seahorse (Hippocampus erectus) is found in the brackish waters of the Lower New York Bay, New York Harbor and surrounding waters (including Raritan Bay and Sandy Hook Bay) and the Hudson River estuary.[132][133][134][135][136]

Marine and invasive species

Marine life is known to exist in the estuary, with seals, crabs, and some whales reported. On March 29, 1647, a white whale swam up the river to the Rensselaerswyck (near Albany). Herman Melville, author of Moby-Dick, lived in and near Albany from 1830 to 1847, and was known to have ancestry from New Netherland, leading some to believe stories of the whale sighting inspired his novel.[137]

Non-native species often originate in New York Harbor, a center of long-distance commerce. Over 100 foreign species reside in the river and its banks. Many of these have had significant effects on the ecosystem and natural habitats. The water chestnut produces a vegetative mat that reduces oxygen content in the water below, enhances sedimentation, impedes small vessel navigation, and is a hazard to swimmers and walkers. The zebra mussel arrived in the Hudson in 1989 and has spread through the river's freshwater region, reducing photoplankton and river oxygen levels. Positively, the mussel clears suspended particles, allowing for more light to aquatic vegetation. In saltwater areas, the green crab spread in the early 20th century and the Japanese shore crab has become dominant in recent years.[39]

Habitats

The Hudson has a diverse array of habitat types. Most of the river consists of deep water habitats, though its tidal wetlands of freshwater and salt marshes are among the most ecologically important. There is strong biological diversity, including intertidal vegetation like freshwater cattails and saltwater cordgrasses. Shallow coves and bays are often covered with submarine vegetation; shallower areas harbor diverse benthic fauna. Abundance of food varies over location and time, stemming from seasonal flows of nutrients. The Hudson's large volume of suspended sediments reduces light penetration in the area's water column, which reduces photoplankton photosynthesis and prevents sub-aquatic vegetation from growing beyond shallow depths. The oxygen-producing phytoplankton have also been inhibited by the relatively recent invasion of the zebra mussel species.[39]

The Hudson River estuary is the site of wetlands from New York City all the way up to Troy. It has one of the largest concentrations of freshwater wetlands in the Northeast. Even though the river can be considered brackish further south, 80 percent of the wetlands are outside the influence of the saltwater coming from the Atlantic Ocean. Currently, the river has about 7,000 acres (28 km2) acres of wetlands, and rising sea levels due to climate change are expected to lead to an expansion of that area. Wetlands are expected to migrate upland as sea level (and thus the level of the river) rises. This is different from the rest of the world, where rising sea levels usually leads to a reduction in wetland areas. The expansion of the wetlands are expected to provide more habitat to the fish and birds of the region.[138]

Activities

Parkland surrounds much of the Hudson River; prominent parks include Battery Park and Liberty State Park at the river's mouth,[139] Riverside Park in Manhattan,[140] Croton Point Park,[141] Bear Mountain State Park,[142] Storm King State Park and the Hudson Highlands,[143] Moreau Lake State Park,[144] and its source in the High Peaks Wilderness Area.[145]

The New Tappan Zee Bridge between Westchester and Rockland counties has a pedestrian and bicycling path covering a distance of about 3.6 miles. Another pedestrian and bike path exists further north, between Dutchess and Ulster Counties: Walkway Over the Hudson, which has a one-way length of 1.2 miles.

Fishing is allowed in the river, although the state Department of Health recommends eating no fish caught from the South Glens Falls Dam to the Federal Dam at Troy. Women under 50 and children under 15 are not advised to eat any fish caught south of the Palmer Falls Dam in Corinth, while others are advised to eat anywhere from one to four meals per month of Hudson River fish, depending on species and location caught. The Department of Health cites mercury, PCBs, dioxin, and cadmium as the chemicals impacting fish in these areas.[146][147]

Common native species recreationally fished include striped bass (formerly a major commercial species, now only legally taken by anglers), channel catfish, white catfish, brown bullhead, yellow perch, and white perch. The nonnative largemouth and smallmouth bass are also popular, and serve as the focus of catch-and-release fishing tournaments.[39]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Hudson River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- 1 2 "Santanoni Peak, NY" 1:25,000 Topographic Quadrangle, 1999, USGS

- 1 2 "Estimates of monthly and annual net discharge, in cubic feet per second, of Hudson River at New York, N.Y." United States Geological Survey (USGS). October 15, 2010. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- 1 2 "Hudson River at Green Island NY". USGS Surface-Water Annual Statistics for the Nation. USGS. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- 1 2 Hudson River Estuary Program; NY-NJ Harbor & Estuary Program; NEIWPCC (October 2020). The State of the Hudson 2020 (PDF) (Report). New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC).

- 1 2 3 4 "Hudson River Cleanup". Hudson River PCBs Superfund Site. New York: US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). October 5, 2021.

- 1 2 "Feature Detail Report for: Hudson River". USGS. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Hudson River, NY". Kanien'kéha. August 24, 2016. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ↑ "Full text of "Aboriginal place names of New York"". Retrieved July 10, 2017.

- ↑ Scott, Andrea K. (December 24, 2018). "Maya Lin". Goings On About Town. The New Yorker. p. 8. Archived from the original on January 12, 2019.

The Mohican name for the Hudson River was Mahicannituc—waters that are never still

- ↑ Miles, Lion G. "Mohican Dictionary" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 19, 2016. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ↑ "Tribes". delawaretribe.org. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ↑ Gennochio, Benjamin (September 3, 2009). "The River's Meaning to Indians, Before and After Hudson". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 23, 2018. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- 1 2 3 History of the County of Hudson, Charles H. Winfield, 1874, p. 1-2

- ↑ Ingersoll, Ernest (1893). Rand McNally & Co.'s Illustrated Guide to the Hudson River and Catskill Mountains. Chicago, Illinois: Rand, McNally & Company. p. 19. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2015.

- ↑ Jacobs, Jaap (2005). New Netherland: A Dutch Colony in Seventeenth-Century America. Netherlands: Brill Publishers. p. 11. ISBN 9004129065. OCLC 191935005. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

- ↑ Steinhauer, Jennifer (May 15, 1994). "Smell of the Forest". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ↑ Stanne, Stephen P.; Panetta, Roger G.; Forist, Brian E. (1996). The Hudson, An Illustrated Guide to the Living River. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813522715. OCLC 32859161. Archived from the original on May 1, 2016. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

- ↑ Roberts, Sam (March 8, 2017). "Some Credit for Henry Hudson, Found in a 280-Year-Old Map". The New York Times.

- ↑ "The Hudson River: Autumn Peace Broods over America's Rhine". Life. October 2, 1939. p. 57. Archived from the original on May 1, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2014.

- ↑ "519 Map of a part of New Netherland, in addition to the newly discovered country, baye with drye rivers, laying at a height of 38 to 40 degrees, by yachts called Onrust, skipper Cornelis Hendricx, van Munnickendam | Nationaal Archief". www.nationaalarchief.nl. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ↑ "Noort Rivier in Niew Neerlandt". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ↑ Juet, Robert (1625). "The third Voyage of Master HENRIE HVDSON". The Kraus Collection of Sir Francis Drake, Library of Congress. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- ↑ Bruce, Wallace (1873). The Hudson River by Daylight: New York to Albany, Saratoga Springs, Lake George ... J. Featherston.

- ↑ "Dutch Racks Revisited: the puzzle of the Hudson River reaches – Saugerties Lighthouse". March 10, 2022. Retrieved July 27, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Freeman, W. O. "National Water Quality Assessment Program – The Hudson River Basin". ny.water.usgs.gov/. USGS. Archived from the original on November 17, 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ↑ Roberts, Brooks (April 10, 1977). "A Hike to the Source of the Hudson River". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 26, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- 1 2 "Lake Tear of the Clouds – Source of the Hudson River". Lake Placid: Adirondacks, USA. Regional Office of Sustainable Tourism. October 8, 2014. Archived from the original on March 26, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ↑ Zahavi, Gerald. "Station 1A: The Source of the Hudson ~ Lake Tear of the Clouds". www.albany.edu/. University of Albany. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Town of Newcomb, Essex County: Historic Tahawus Tract". www.apa.ny.gov/. Adirondack Park Agency. Archived from the original on May 31, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Location of the Site in New York (Map). USGS. Archived from the original on December 31, 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ↑ Google (March 25, 2018). "Lake Tear of the Clouds" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- 1 2 Morrissey, Spencer (April 23, 2015). "Finding the Sources of the Hudson near Upper Works". Schroon Lake Region. Archived from the original on March 26, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ↑ Brown, Phil. "Paddling the Upper Hudson and Opalescent Rivers". Adirondack Almanack. Archived from the original on March 26, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ↑ "Wild, Scenic and Recreational Rivers". NYSDEC. Archived from the original on March 26, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ↑ Winslow, Mike. "On Closing the Champlain Canal". www.lakechamplaincommittee.org. Lake Champlain Committee. Archived from the original on December 31, 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Aimon, Alan C. (November 27, 2009). "River Guide to the Hudson Highlands" (PDF). Hudson River Valley Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 30, 2011. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- 1 2 "George Washington Bridge". The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on September 20, 2013. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "The Hudson River Today". The River Project. Archived from the original on January 17, 2018. Retrieved January 16, 2018., from Levinton, Jeffrey S.; Waldman, John R., eds. (2006). The Hudson River Estuary. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Rittner, Don (2002). Troy, NY: A Collar City History. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-2368-2. Archived from the original on January 6, 2016. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

- ↑ "Waterfront park/walkway connects Hoboken to Weehawken". Fund for a Better Waterfront. April 3, 2012. Archived from the original on March 8, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- ↑ Wu, Amy (February 23, 2018). "Communities that drink from Hudson River push for further water protection". Poughkeepsie Journal.

- 1 2 3 Adams, Arthur G. (1996). The Hudson River Guidebook (2nd ed.). New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 0-8232-1679-9. LCCN 96-1894. Archived from the original on March 20, 2015. Retrieved September 27, 2017.

- 1 2 Levinton, Jeffrey S.; Waldman, John R. (2006). The Hudson River Estuary (PDF). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–10. ISBN 0521207983. OCLC 60245415. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ↑ "21. The Hudson as Fjord". New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC). Archived from the original on July 5, 2010. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ↑ John Waldman; Heartbeats in the Muck; ISBN 1-55821-720-7 The Lyons Press; (2000)

- 1 2 3 4 Alfieri, J.; Berardis, A.; Smith, E.; Mackin, J.; Muller, W.; Lake, R.; Lehmkulh, P. (June 3, 1999). "The Lenapes: A study of Hudson Valley Indians". Poughkeepsie, New York: Marist College. Archived from the original on December 8, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Levine, David (June 24, 2016). "Hudson Valley's Tribal History". Hudson Valley Magazine. Archived from the original on May 24, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Giovanni Verrazano". The New York Times. September 15, 1909.

- ↑ De Laet, Johan (1909). "New World, Chapter 7," Narratives of New Netherland, 1609-1664. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 37. Retrieved April 17, 2023.

- ↑ Collier, Edward (1914). A History of Old Kinderhook from Aboriginal Days to the Present Time. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 2–7. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- ↑ Cleveland, Henry R. "Henry Hudson Explores the Hudson River". history-world.org. International World History Project. Archived from the original on July 5, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - 1 2 3 4 "Dutch Colonies". National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ↑ Rink, Oliver A. (1986). Holland on the Hudson: An Economic and Social History of Dutch New York. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. pp. 17–23, 264–266. ISBN 978-0801495854.

- 1 2 Roberts, Sam (August 25, 2014). "350 Years Ago, New Amsterdam Became New York. Don't Expect a Party". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 1, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ↑ Leitner, Jonathan (2016). "Transitions in the Colonial Hudson Valley: Capitalist, Bulk Goods, and Braudelian". Journal of World-Systems Research. 22 (1): 214–246. doi:10.5195/JWSR.2016.615.

- ↑ Bielinski, Stefan. "The Albany Congress". The Albany Congress. New York State Museum. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ↑ "City Hall". New York State Museum. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Albany Plan of Union, 1754". Milestones: 1750–1775. Office of the Historian. Archived from the original on January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Albany Congress". American History Central. R.Squared Communications LLC. Archived from the original on January 5, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ↑ Mansinne, Major Andrew Jr. "The West Point Chain and Hudson River Obstructions in the Revolutionary War" (PDF). desmondfishlibrary.org. Desmond Fish Library. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ↑ Carroll, John Martin; Baxter, Colin F. (August 2006). The American Military Tradition: From Colonial Times to the Present (2nd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc. pp. 14–18. ISBN 9780742544284. Archived from the original on April 30, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ↑ Hevesi, Dennis (August 27, 1993). "A Crucial Battle in the Revolution". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- ↑ Shepherd, Joshua (April 15, 2014). ""Cursedly Thrashed": The Battle of Harlem Heights". Journal of the American Revolution. Archived from the original on February 19, 2016. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

- ↑ Borkow, Richard (July 2013). "Westchester County, New York and the Revolutionary War: The Battle of White Plains (1776)". Westchester Magazine. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ↑ Mark, Steven Paul (November 20, 2013). "Too Little, Too Late: Battle Of The Hudson Highlands". Journal of the American Revolution. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ↑ Harrington, Hugh T. (September 25, 2014). "he Great West Point Chain". Journal of the American Revolution. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

- ↑ Kornhauser, Elizabeth Mankin; Ellis, Amy; Miesmer, Maureen (2003). Hudson River School: Masterworks from the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. p. vii. ISBN 0300101163. Archived from the original on January 3, 2017. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ↑ "The Panoramic River: the Hudson and the Thames". Hudson River Museum. 2013. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-943651-43-9. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- 1 2 Avery, Kevin J. (October 2004). "The Hudson River School". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on June 14, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ↑ "The Hudson River School: Nationalism, Romanticism, and the Celebration of the American Landscape". Virginia Tech History Department. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ↑ Nicholson, Louise (January 19, 2015). "East meets West: The Hudson River School at LACMA". Apollo. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ↑ Oelschlaeger, Max. "The Roots of Preservation: Emerson, Thoreau, and the Hudson River School". Nature Transformed. National Humanities Center. Archived from the original on June 23, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ↑ O'Toole, Judith H. (2005). Different Views in Hudson River School Painting. Columbia University Press. p. 11. ISBN 9780231138208. Archived from the original on May 13, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2016.

- ↑ Boyle, Alexander. "Thomas Cole (1801–1848). The Dawn of the Hudson River School". Hamilton Auction Galleries. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Canal History". www.canals.ny.gov. New York State Canal Corporation. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Canal Era". www.ushistory.org/. U.S. History. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ↑ "Erie Canalway". www.eriecanalway.org. Erie Canalway. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Finch, Roy G. "The Story of the New York State Canals" (PDF). www.canals.ny.gov. New York State Canals Corporation. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ↑ Levine, David (August 2010). "How the Delaware & Hudson Canal Fueled the Valley". Hudson Valley Magazine. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ↑ Harmon, Daniel E. (2004). "The Hudson River". Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 9781438125183. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ↑ Hunter, Louis C. (1985). A History of Industrial Power in the United States, 1730–1930, Vol. 2: Steam Power. Charlottesville, Virginia: University Press of Virginia.

- ↑ Aggarwala, Rohit T. "The Hudson River Railroad and the Development of Irvington, New York, 1849,1860" (PDF). The Hudson Valley Regional Review: 51–80. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 23, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2017.

- ↑ Johnson, Carl. "The Livingston Avenue Bridge". All Over Albany. Uptown/Downtown Media LLC. Archived from the original on September 9, 2017. Retrieved June 5, 2017.

- ↑ "The Albany Railroad Bridge". Catskill Archive. Harper's Weekly. Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved June 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Freight Rail Service in New York State". New York State Department of Transportation. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Opening the West Shore" (PDF), The New York Times, June 5, 1883, archived (PDF) from the original on November 20, 2021, retrieved June 5, 2017

- 1 2 "History: Timeline". Walkway Over the Hudson. Archived from the original on April 1, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ↑ Blakinger, Keri (April 11, 2016). "Spanning the decades: A look at the history of New York City's tunnels and bridges". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on May 1, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ↑ "This Day in History: November 21". History Channel. Archived from the original on June 14, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Bridges and Tunnels History". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on May 29, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ↑ Hughes, C. J. (August 20, 2012). "Hudson Valley Bridges: Crossings and Spans Over the Hudson River". Hudson Valley Magazine. Archived from the original on September 9, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ↑ Plotch, Philip Mark (September 7, 2015). "Lessons From the Tappan Zee Bridge". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ↑ Berger, Joseph (January 19, 2014). "A Colossal Bridge Will Rise Across the Hudson". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- 1 2 Hammonds, Keith H. (September 11, 1995). "The Town IBM Left Behind". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on September 9, 2017. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- 1 2 Lueck, Thomas J. (June 27, 1996). "Auto Plant Closes and Developers See Opportunity; North Tarrytown Focuses on its Future Instead of the Past". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved June 18, 2017.

- ↑ "New York State Museum – "Swim for the River"". Archived from the original on August 19, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- ↑ Goldberger, Paul (April 2011). "New York's High Line". National Geographic. Archived from the original on June 10, 2017. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- ↑ Applebome, Peter (August 5, 2011). "Williamsburg on the Hudson". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- ↑ Hudson River Valley National Heritage Area (PDF) (Map). Hudson River Valley Greenway. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ↑ "The Hudson River National Historic Landmark District". Hudson River Heritage. Archived from the original on November 18, 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ↑ Clinton, William Jefferson (July 30, 1998). "Designation of American Heritage Rivers" (PDF). United States Government Printing Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 8, 2014. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve". Hudson River National Estuarine Research Reserve. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2015.

- ↑ Canal Map (Map). New York State Canal Corporation. Archived from the original on June 11, 2017. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- ↑ "Lock Information". Canal Corporation. New York State Canal Corporation. Archived from the original on June 6, 2017. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- 1 2 Metro-North Railroad (Map). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2011. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- ↑ Anderson, Eric (October 18, 2011). "Amtrak leasing track corridor". Times Union. Archived from the original on September 9, 2017. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ↑ Fries, Amanda (August 14, 2016). "Jersey-bound train sideswipes cars in derailment at Selkirk yard". Times Union. Archived from the original on September 9, 2017. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ↑ "North Bergen, NJ << View locations served". Channel Partners. CSX Transportation. Archived from the original on June 1, 2017. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Troy Union Bridge Burned" (PDF). The New York Times. July 11, 1909. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ↑ Crowe II, Kenneth C. (November 22, 2013). "Crack closes bridge over Hudson River". Times Union. timesunion.com. Archived from the original on February 5, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ↑ Whittemore, Whitemore (1909). "Fullfilment of the Remarkable Prophecies Relating to the Development of Railroad Transportation". Catskill Archives. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ↑ McLaren, Megan (July 19, 2010). "A lot of history behind this bridge". Troy, New York: The Record News. Archived from the original on March 15, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ↑ Google (March 14, 2018). "Troy Lock to Green Island Bridge" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ↑ Hudson River Maritime Museum staff. "The Hudson River Day Line - 1863-1971". Hudson River Maritime Museum. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

- ↑ Kenneth J. Blume (2012). "Hudson River Day Line". Historical Dictionary of the U.S. Maritime Industry. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810856349.

- ↑ William H. Ewen (2011). "Hudson River Day Line". Steamboats on the Hudson River. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738574158.

- ↑ "Ecological Risk Assessment". Hudson River PCBs. New York, NY: EPA. August 1999. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- ↑ Levinton, J.S.; Ochron, S.T.P. (2008). "Temporal and geographic trends in mercury concentrations in muscle tissue in five species of hudson river, USA, fish". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 27 (8): 1691–1697. doi:10.1897/07-438.1. PMID 18266478. S2CID 86320742.

- ↑ "Hudson River Estuary Program: Cleaning the river: Improving water quality" (PDF). Albany, NY: NYSDEC. 2007. p. 24. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- ↑ "About us". Waterkeeper Alliance. Archived from the original on March 15, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- ↑ Harrington, Gerry (January 31, 2014). "Movement afoot to name bridge after Pete Seeger". United Press International. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved February 3, 2014.

- ↑ Kraft, Michael E. (2000). "U.S. Environmental Policy and Politics: From the 1960s to the 1990s". Journal of Policy History. Cambridge University Press. 12 (1): 23. doi:10.1353/jph.2000.0006. S2CID 154099488.

- ↑ Hays, Samuel P. (October 1981). "The Environmental Movement". Journal of Forest History. 25 (4): 219–221. doi:10.2307/4004614. JSTOR 4004614. S2CID 201270765.

- 1 2 "How is the Hudson Doing?". Hudson River Estuary Program. NYSDEC. Archived from the original on November 19, 2017. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- ↑ Lake, Tom (October 20, 2016). "Hudson River Watershed Fish Fauna Check List" (PDF). NYSDEC Hudson River Estuary Program. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 20, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ↑ Kaminsky, Peter (January 6, 1991). "Outdoors; Striped Bass and the Big City". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ↑ Antonucci, Claire; Higgins, Rosemary; Yuhas, Cathy. "Atlantic Striped Bass" (PDF). New Jersey Sea Grant Consortium Extension Program. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 1, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Fish". Hudson River Park Trust. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ↑ Welsh, Jennifer (February 17, 2011). "Fish Evolved to Survive GE Toxins in Hudson River". LiveScience. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ↑ Rittner, Don (June 4, 2013). "Welcome to Sturgeonville". Albany Times Union. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Spot a Seahorse in NYC". Slow Nature Fast City. July 20, 2016. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ↑ Pereira, Sydney (April 18, 2021). "Seahorse Spotted In The Hudson River, Marking Yet Another Hopeful Sign Of Spring". Gothamist. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ↑ "Seahorses Really Do Swim in NY Harbor". NY HARBOR NATURE. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ↑ "There are seahorses living in New York City". Grist. October 4, 2012. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ↑ Gonzalez • •, Georgina (April 16, 2021). "The Many Creatures of the Hudson River May Surprise You". NBC New York. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ↑ Walker, Ruth (March 28, 2002). "A whale of a tale from old Albany". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ↑ Friedlander, Blaine (June 29, 2016). "As sea level rises, Hudson River wetlands may expand". Cornell Chronicle. Archived from the original on December 8, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions About Directions: Directions to Statue Cruises". Statue Cruises. Archived from the original on July 4, 2017. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Riverside Park". New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on March 25, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Croton Point Park". Westchester County. Archived from the original on March 25, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Bear Mountain State Park". New York State Office of Parks and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on April 21, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ↑ Revkin, Andrew C. (April 14, 2015). "How a Hudson Highlands Mountain Shaped Tussles Over Energy and the Environment". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 25, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Moreau Lake State Park". New York State Office of Parks and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on March 25, 2018. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ↑ Shapley, Dan (December 23, 2016). "Protecting Hudson River headwaters in the High Peaks". Riverkeeper. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Hudson River & Tributaries Region Fish Advisories". New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH). April 2017. Archived from the original on September 13, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ↑ "Hudson River: Health Advice on Eating Fish You Catch" (PDF). NYSDOH. February 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

Further reading

| Library resources about Hudson River |

- Adams, Arthur G. (1996). The Hudson River Guidebook (2nd ed.). New York: Fordham University Press. ISBN 0-8232-1679-9. LCCN 96-1894. For a comprehensive guide to aspects of the river.

External links

- Hudson River Maritime Museum

- Beczak Environmental Education Center

- Tocqueville in Newburgh – an Alexis de Tocqueville Tour segment on Hudson River steamship travel in the 1830s