The geography of New York City is characterized by its coastal position at the meeting of the Hudson River and the Atlantic Ocean in a naturally sheltered harbor. The city's geography, with its scarce availability of land, is a contributing factor in making New York the most densely populated major city in the United States. Environmental issues are chiefly concerned with managing this density, which also explains why New York is among the most energy-efficient and least automobile-dependent cities in the United States. The city's climate is temperate.

Geography

New York City is located on the coast of the Northeastern United States at the mouth of the Hudson River in southeastern New York state. It is located in the New York–New Jersey Harbor Estuary, the centerpiece of which is the New York Harbor, whose deep waters and sheltered bays helped the city grow in significance as a trading city. Much of New York is built on the three islands of Manhattan, Staten Island, and western Long Island, making land scarce and encouraging a high population density.

.jpg.webp)

The Hudson River flows from the Hudson Valley into New York Bay, becoming a tidal estuary that separates the Bronx and Manhattan from Northern New Jersey. The Harlem River, another tidal strait between the East and Hudson Rivers, separates Manhattan from the Bronx.

The city's land has been altered considerably by human intervention, with substantial land reclamation along the waterfronts since Dutch colonial times. Reclamation is most notable in Lower Manhattan with modern developments like Battery Park City. Much of the natural variations in topography have been evened out, particularly in Manhattan.[1] The West Side of Manhattan retains some hilliness, especially in Upper Manhattan, while the East Side has been considerably flattened. Duffy's Hill in East Harlem is one notable exception to the East Side's relatively level grade.

The city's land area is estimated to be 321 square miles (830 km2).[2] However, a more recent estimate calculates a total land area of 304.8 square miles (789.4 km2).[3] Icebergs are often compared in size to the area of Manhattan.[4][5][6]

The highest natural point in the city is Todt Hill on Staten Island, which at 409.8 ft (124.9 m) above sea level is the highest hill on the Eastern Seaboard south of Maine. The summit of the ridge is largely covered in woodlands as part of the Staten Island Greenbelt. Many places have been identified as the geographic center of the city, including a plaque in the center of Queens Boulevard and 58th Street, in Woodside, Queens.[7]

Geology

The boroughs of New York City straddle the border between two geologic provinces of eastern North America. Brooklyn and Queens, located on Long Island, are part of the eastern coastal plain. Long Island is a massive moraine which formed at the southern fringe of the Laurentide Ice Sheet during the last ice age. The Bronx and Manhattan lie on the eastern edge of the Newark Basin, a block of the Earth's crust which sank downward during the disintegration of the supercontinent Pangaea during the Triassic period. The Palisades Sill on the New Jersey shore of the Hudson River exposes ancient, once-molten rock that filled the basin. The bedrock underlying much of Manhattan is a mica schist known as Manhattan schist[8] of the Manhattan Prong physiographic region. It is a strong, competent metamorphic rock that was produced when Pangaea formed. It is well suited for the foundations of tall buildings. In Central Park, outcrops of Manhattan schist occur and Rat Rock is one rather large example.[9][10][11]

Geologically, a predominant feature of the substrata of Manhattan is that the underlying bedrock base of the island rises considerably closer to the surface near Midtown Manhattan, dips down lower between 29th Street and Canal Street, then rises toward the surface again in Lower Manhattan. It has been widely believed that the depth to bedrock was the primary underlying reason for the clustering of skyscrapers in the Midtown and Financial District areas, and their absence over the intervening territory between these two areas.[12][13] However, research has shown that economic factors played a bigger part in the locations of these skyscrapers.[14][15][16]

According to the United States Geological Survey, an updated analysis of seismic hazard in July 2014 revealed a "slightly lower hazard for tall buildings" than previously assessed. Scientists estimated this lessened risk based upon a lower likelihood than previously thought of slow shaking near New York City, which would be more likely to cause damage to taller structures from an earthquake in the vicinity of the city.[17]

Adjacent counties

Boroughs

New York City comprises five boroughs, an unusual form of government used to administer the five constituent counties that make up the city. Throughout the boroughs there are hundreds of distinct neighborhoods, many with a definable history and character all their own. If the boroughs were each independent cities, four of the boroughs (Brooklyn, Queens, Manhattan, and the Bronx) would be among the ten most populous cities in the United States.

- The Bronx (Bronx County, pop. 1,364,566)[18] is New York City's northernmost borough. It is the birthplace of rap and hip hop culture,[19] the site of Yankee Stadium, and home to the largest cooperatively owned housing complex in the United States, Co-op City.[20] Except for a small piece of Manhattan known as Marble Hill, the Bronx is the only section of the city that is part of the North American mainland.

- Brooklyn (Kings County, pop. 2,511,408)[18] is the city's most populous borough and was an independent city until 1898. Brooklyn is known for its cultural diversity, an independent art scene, distinct neighborhoods and a unique architectural heritage. The borough also features a long beachfront and Coney Island, famous as one of the earliest amusement grounds in the country.

- Manhattan (New York County, pop. 1,606,275)[18] is the most densely populated borough and home to most of the city's skyscrapers. The borough contains the major business centers of the city and many cultural attractions. Manhattan is loosely divided into downtown, midtown, and uptown regions.

- Queens (Queens County, pop. 2,256,576)[18] is geographically the largest borough and the most ethnically diverse county in the United States.[21] Historically a collection of small towns and villages founded by the Dutch, the borough today is mainly residential and middle class, with enclaves of above average income and wealth. It is the only large county in the United States where the median income among African-American households, about $52,000 a year, has surpassed that of Caucasian households.[22] Queens is the site of Citi Field and its predecessor Shea Stadium, the home of the New York Mets, and annually hosts the US Tennis Open.

- Staten Island (Richmond County, pop. 475,014)[18] is the most suburban in character of the five boroughs. It is connected to Brooklyn by the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge and to Manhattan by the free Staten Island Ferry. Until 2001 the borough was home to the Fresh Kills Landfill, formerly the largest landfill in the world, which is now being reconstructed as Freshkills Park, one of the largest urban parks in the United States.

Environmental issues

New York City plays an important role in the green policy agenda because of its size. Environmental groups make large efforts to help shape legislation in New York because they see the strategy as an efficient way to influence national programs. New York City's economy is larger than Switzerland's, a size that means the city has potential to set new de facto standards. Manufacturers are also attuned to the latest trends and needs in the city because the market is simply too big to ignore.

Although cities like San Francisco or Portland, Oregon are most commonly associated with urban environmentalism in the United States, New York City's unique urban footprint and extensive transportation systems make it more sustainable than most American cities.

Maps and satellite images

New Amsterdam in 1660

New Amsterdam in 1660 One of the 1770 Ratzer Maps

One of the 1770 Ratzer Maps New York City and the city of Brooklyn, in 1885

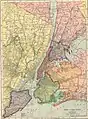

New York City and the city of Brooklyn, in 1885 New York City area in 1906

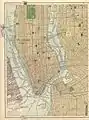

New York City area in 1906 Downtown New York City in 1910

Downtown New York City in 1910 False-color satellite image

False-color satellite image Thermal image (blue is warm, yellow is hot)

Thermal image (blue is warm, yellow is hot) Vegetation is beige (sparse) and deep green (dense)

Vegetation is beige (sparse) and deep green (dense) Satellite photograph of southern Manhattan taken in 2002

Satellite photograph of southern Manhattan taken in 2002

See also

References

Notes

Sources

- ↑ Lopate, Phillip (2004). Waterfront: A Walk Around Manhattan. Anchor Press. ISBN 0-385-49714-8.

- ↑ "Land Use Facts". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on 2007-03-30. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ↑ Roberts, Sam (2008-05-22). "It's Still a Big City, Just Not Quite So Big". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-05-22.

- ↑ Zamira Rahim (September 14, 2020). "A chunk of ice twice the size of Manhattan has broken off Greenland in the last two years". CNN. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- ↑ Maddie Stone (February 21, 2019). "An Iceberg 30 Times the Size of Manhattan Is About to Break Off Antarctica". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on October 27, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- ↑ Lorraine Chow (November 1, 2018). "An iceberg 5 times bigger than Manhattan just broke off from Antarctica". Business Insider. Archived from the original on October 27, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- ↑ "This Spot in Queens Claims to be the Center of NYC. It's Not". www.ny1.com. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ↑ The fact that the immediate layer of bedrock in the Bronx is Fordham gneiss, while that of Manhattan is schist has led to the expression: "The Bronx is gneiss (nice) but Manhattan is schist." Eldredge, Niles and Horenstein, Sidney (2014). Concrete Jungle: New York City and Our Last Best Hope for a Sustainable Future. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 42, n1. ISBN 978-0-520-27015-2.

- ↑ "Manhattan Schist in Bennett Park". February 4, 2019. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012.

- ↑ John H. Betts The Minerals of New York City Archived March 13, 2020, at the Wayback Machine originally published in Rocks & Minerals magazine, Volume 84, No. 3 pages 204–252 (2009).

- ↑ Samuels, Andrea. "An Examination of Mica Schist by Andrea Samuels, Micscape magazine. Photographs of Manhattan schist". Microscopy-uk.org.uk. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Manhattan Schist in New York City Parks – J. Hood Wright Park". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Archived from the original on March 3, 2014. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

- ↑ Quinn, Helen (June 6, 2013). "How ancient collision shaped New York skyline". BBC Science. BBC.co.uk. Archived from the original on June 13, 2013. Retrieved June 13, 2013.

These rocks are Manhattan schist, part of that ancient supercontinent, fragments of Pangaea left behind when the continent split. They are just glimpses of what is below the surface in abundance in Downtown and Midtown. And it is these fragments of very hard rock that provide the perfect foundations for New York's highest buildings. Where Manhattan schist can be found very close to the surface you can build high, and so Downtown and Midtown have become home to Manhattan's tallest buildings.

- ↑ Jason Barr; Tassier, Troy; and Trendafilov, Rossen. "Depth to Bedrock and the Formation of the Manhattan Skyline, 1890–1915" Archived April 25, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, The Journal of Economic History, December 2011 – Volume 71, Issue 04. Accessed August 3, 2016.

- ↑ Chaban, Matt (January 17, 2012). "Uncanny Valley: The Real Reason There Are No Skyscrapers in the Middle of Manhattan". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on March 2, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ↑ Chaban, Matt (January 25, 2012). "Paul Goldberger and Skyscraper Economist Jason Barr Debate the Manhattan Skyline" (PDF). The New York Observer. Archived from the original on March 2, 2014. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ↑ Jessica Robertson & Mark Petersen (July 17, 2014). "New Insight on the Nation's Earthquake Hazards". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on August 11, 2014. Retrieved August 12, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "New York State Department of Labor - Population Estimates". Archived from the original on 2007-01-04. Retrieved 2006-11-02.

- ↑ Toop, David (1992). Rap Attack 2: African Rap to Global Hip-Hop. Serpents Tail. ISBN 1-85242-243-2.

- ↑ Frazier, Ian (2006-06-26). "Utopia, the Bronx". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2007-03-26.

- ↑ O'Donnell, Michelle (2006-07-04). "In Queens, It's the Glorious 4th, and 6th, and 16th, and 25th..." New York Times. Retrieved 2006-07-19.

- ↑ Roberts, Sam (2006-01-10). "Black Incomes Surpass Whites in Queens". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-03-28.

Further reading

- The Vegan Guide to New York City, by Rynn Berry and Chris A. Suzuki

- The Big Green Apple: Your Guide to Eco-Friendly Living in New York City, by Mathieu Fontaine

- John H. Betts The Minerals of New York City originally published in Rocks & Minerals magazine, Volume 84, No . 3 pages 204-252 (2009).

External links

- Green Apple Map - Interactive green map of New York City's environmental resources.

- NYC Open Accessible Space Information System - Interactive mapping resource of open space in New York City.

- Council on the Environment of New York City (CENYC) - Privately funded citizens' organization in the Office of the Mayor of New York City.

- NYCityMap - New York City Government interactive map