| Part of a series on |

| 2022 Commonwealth Games |

|---|

|

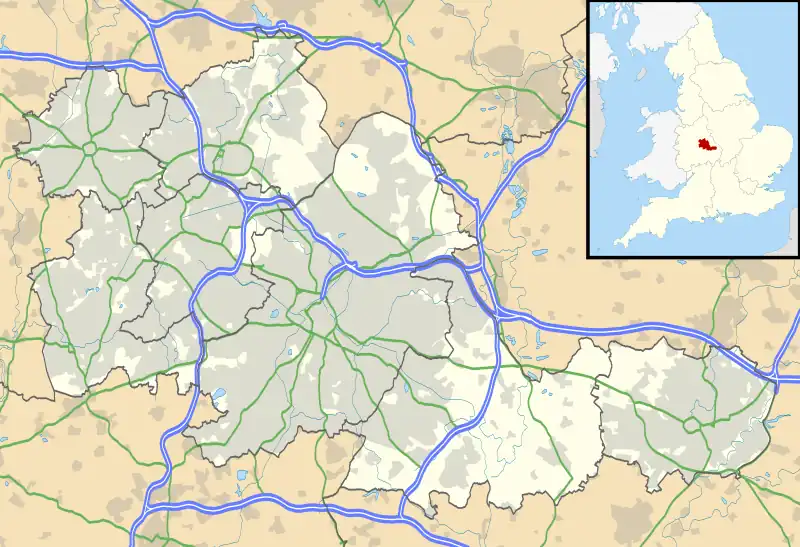

The venues for the 2022 Commonwealth Games will be based in Birmingham, Cannock Chase, Coventry, Royal Leamington Spa, Sandwell, Solihull, Warwick, Wolverhampton, and London.

Venues

The following venues will be used for the Games:[1]

| Venue | Image | Location | Facility | Status | Year opened | Ticketed Capacity | Events | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City of Birmingham | ||||||||||

| Alexander Stadium |  |

Perry Barr | Stadium | Renovated | 2022 | 32,000 | Ceremonies | [2] | ||

| Athletics | ||||||||||

| Arena Birmingham |  |

Westside | Main Arena | Existing | 1991 | 15,800 | Artistic Gymnastics | [3] | ||

| Rhythmic Gymnastics | ||||||||||

| Edgbaston Cricket Ground | .jpg.webp) |

Edgbaston | Stadium | Existing | 1886 | 25,000 | Women's T20 Cricket | [4] | ||

| Smithfield |  |

Southside | Beach Volleyball Arena | Temporary Arena | – | 4,000 | Beach Volleyball | [5] | ||

| 3x3 Basketball Arena | Temporary Arena | 2,500 | 3x3 Basketball | |||||||

| – | – | – | Marathon (start) | |||||||

| Sutton Park |  |

Sutton Coldfield | Open Water Pool | – | – | – | Triathlon | [6] | ||

| Park Trails | Temporary Grandstand | 2,000 | ||||||||

| University of Birmingham | Edgbaston | Hockey Pitches | Upgraded / Temporary Arena | 2017 | 6,000 | Field Hockey | [7] | |||

| Squash Centre | Upgraded / Temporary Arena | 2,000 | Squash | |||||||

| Victoria Square |  |

City Centre | Main Square | Existing | – | – | Marathon (finish) | [8] | ||

| West Midlands Region | ||||||||||

| Cannock Chase Forest | .jpg.webp) |

Cannock Chase | Mountain Bike Trails | Upgraded | 2005 | – | Mountain Biking | [9] | ||

| Coventry Stadium and Arena |  |

Coventry | Stadium | Existing | 2005 | 32,609 | Rugby Sevens | [10] | ||

| Arena | 8,000 | Judo | ||||||||

| Wrestling | ||||||||||

| Victoria Park |  |

Leamington Spa | Bowling Greens A–E | Upgraded | – | 5,000 | Lawn Bowls | [11] | ||

| Sandwell Aquatics Centre | Sandwell | 50m Swimming Pool | New-build | 2022 | 4,000 | Swimming | [12] | |||

| Diving Pool | Diving | |||||||||

| National Exhibition Centre |  |

Solihull | Hall 1 | Existing | 1976 | 4,500 | Weightlifting | [13] | ||

| Para Powerlifting | ||||||||||

| Hall 3 | 3,500 | Table Tennis | ||||||||

| Para Table Tennis | ||||||||||

| Hall 4 | 12,000 | Boxing | ||||||||

| Hall 5 | 8,000 | Badminton | ||||||||

| NEC Arena |  |

Solihull | Main Arena | Existing | 1980 | 15,685 | Netball | [13] | ||

| Myton Fields | Warwick | Grassed area and adjacent road | Existing | – | – | Cycling Road Race | [14] | |||

| West Park |  |

Wolverhampton | Park Pathways | Existing | – | – | Cycling Time Trials | [15] | ||

| Greater London | ||||||||||

| Lee Valley VeloPark |  |

Stratford, London | Velodrome | Existing | 2011 | 6,750 | Track Cycling | [16] | ||

Newly constructed and renovated venues

Alexander Stadium, Birmingham

Alexander Stadium is an international athletics stadium located within Perry Park in Perry Barr, Birmingham. It will host the opening and closing ceremonies of the Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games, as well as the Games’ athletics programme.

The stadium was first opened in 1976 and became home to Birchfield Harriers, one of the best known athletics clubs in the United Kingdom.[17] In 2011, it underwent a £12.5 million expansion and refurbishment, including construction of a 5,000-seater stand opposite the main stand, taking the total capacity to 12,700.[18] The new stand also became home to the offices of UK Athletics.[19] Since the expansion, the stadium has hosted annual British Grand Prix events,[20] the Amateur Athletics Association Championships, the 1998 Disability World Athletics Championships and, until 2019, regular English Schools' Athletics Championships.[21]

In June 2017, during the preparation of the Birmingham bid for the 2022 Commonwealth Games, the Birmingham bid committee proposed to renovate the Alexander Stadium and use it for hosting the athletics and ceremonies of the Games.[22] However, UK Athletics Chief Ed Warner argued that the London Stadium, built to host the 2012 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games, should be used to host the athletic events instead, with the rest of the sporting events being held in Birmingham and the West Midlands, to reduce the cost burden of the Games.[23] Warner’s position was not supported by the UK Government, or anyone else, and on 11 April 2018, then Prime Minister Theresa May announced that £70 million of investment would be earmarked to transform the Alexander Stadium into a world-class athletics venue for the 2022 Commonwealth Games to seat 40,000 spectators.[24] In October 2018, British engineering and design firm Arup was chosen by the Birmingham City Council to redesign the stadium[25] and construction firm Mace chosen to manage the renovation project.[26]

In February 2019, Birmingham City Councillor Paul Tilsley claimed that the refurbished Alexander Stadium would become a white elephant after the Games as no long-term tenant for the stadium had been identified. He was also concerned about the funding arrangement of the Games and claimed that spending funds in organising the Games could put the council into heavy debt.[27][28] Nonetheless, on 21 June 2019, Birmingham City Council released the images and plans for renovating the Alexander Stadium and claimed that it would create a legacy asset for the surrounding Perry Barr area. The council suggested that the stadium could become the permanent home for the UKA and host major athletics events including the annual Diamond League meet, which is currently held at the London Stadium.[29] On 30 January 2020, Birmingham City Council's planning committee approved the renovation plans for Alexander Stadium at a cost of £72 million.[30][31][32]

In March 2020, the city council appointed the Northern Irish firm McLaughlin & Harvey to redevelop the stadium.[33] The redevelopment was completed by spring of 2022, in time for the Games.[34] The stadium's seating capacity was increased permanently from 12,700 to 18,000 and will accommodate around 32,000 spectators during the Games, with the installation of additional temporary seating.[35] After the games, the temporary stands around the track bends will be removed, leaving the two permanent stands seating 18,000, with the option of extending the stadium for major events such as the Diamond League and UK Championships.[36][31][32]

On 22 May 2022, the newly renovated stadium played host to its first event, the Birmingham meeting of the Diamond League series, with around 16,000 spectators in attendance. Considered a test event for Birmingham 2022, the meeting was staged successfully and the upgraded stadium received positive reviews from spectators and athletes alike, with Olympic pole-vault bronze medallist Holly Bradshaw describing it as the "most beautiful" track and field venue in the United Kingdom.[37]

Smithfield, Birmingham

Smithfield is a vacant 42 acres (17 ha) site in Birmingham City Centre, bounded by St Martin in the Bull Ring and the BullRing Shopping Centre to the north west, Birmingham’s Chinese Quarter and Gay Village to the south west, and Digbeth to the east. Originally the site of the Birmingham Manor House, Smithfield was established as a trading district by the Birmingham Street Commissioners with the opening of Smithfield Market on 29 May 1817.[38][39] Predominantly a livestock market at first, Smithfield was expanded throughout the nineteenth century[40] and continued to trade in produce and second-hand goods until the 1960s, whereupon the land was purchased by Birmingham City Council and the majority of the site subsequently repurposed as Birmingham Wholesale Markets, the largest in the UK at the time.[41] In 2018, the wholesale markets were relocated to a purpose-built hub in Witton and the entire Smithfield site cleared in preparation for a huge £1.9 billion city centre regeneration project.[42]

Smithfield will be transformed into a multi-use venue for the duration of the Games. It will host the beach volleyball and basketball 3x3 competitions, for which temporary stadia of 4,000 and 2,500 spectators respectively are being constructed,[43] and will also be the start point for the men’s marathon, women’s marathon and men’s and women’s T53/T54 wheelchair events. In addition, it will host one of two planned city centre Festival Sites, with giant screens, live and digital performances, and food and beverage outlets, which will be open to the public.[44]

Sandwell Aquatics Centre

Sandwell Aquatics Centre is the only permanent venue built specifically for Birmingham 2022.[45] It is an indoor facility located in the Londonderry district of Smethwick, Sandwell, containing an Olympic-size swimming pool, a 10-metre diving board with 25 metre pool,[46] a community swimming pool and permanent seating for 1,000 spectators with expanded seating capacity during the Games.[45]

British firm Wates designed the centre and is building it at a cost of £73 million.[47][48] Funding has come from several sources. Sandwell Metropolitan Borough Council is contributing £27 million, with £38.5 million coming from the overall Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games budget. A further £7.6 million has come from Sport England, Black Country LEP, Sandwell Leisure Trust (SLT) and University of Wolverhampton.[49] Construction began in January 2020 and will be completed in time for the Games.

After Birmingham 2022, the centre will undergo redevelopment and will officially open for public use in May 2023 when it will be operated by the Sandwell Leisure Trust.[50] During the redevelopment, seating used for the Games will be removed and new facilities created, including two 4-court sports halls, a 108-station gym, a 28-station ladies-only gym, three activity studios, an indoor cycling studio, a sauna, a steam room, a football pitch with changing facilities, a dry diving area, an urban park and children's playground, and a café.[51]

Existing venues

Arena Birmingham

Arena Birmingham is a multi-purpose indoor arena located in the Westside district of central Birmingham, with a capacity of up to 15,800.[52] When it opened in 1991 as the National Indoor Arena, it was the largest of its type in the country,[53] and is currently the third-largest indoor arena in the United Kingdom by capacity. Each year the venue hosts over 100 events and welcomes around 700,000 visitors through its doors.[54]

The Arena is located alongside the Birmingham Canal Navigations Main Line's Old Turn Junction, opposite the National Sea Life Centre in Brindleyplace, and close to the International Convention Centre (ICC) and Birmingham Symphony Hall, which are also owned and operated by the Arena'a parent company, NEC Group. Between June 2013 and November 2014, the Arena underwent a £26 million redevelopment, designed by the architecture practice Broadway Malyan, which included creating a showpiece entrance from the canal-side, three "sky needle" light sculptures, a new glazed facade fronting the canal and new pre-show hospitality elements.[55]

Since 15 April 2020, the Arena has been known as the Utilita Arena Birmingham,[56] although it will revert to its unsponsored name for the duration of the Games. It will host the Artistic Gymnastics competition from 29 July to 2 August and the Rhythmic Gymnastics competition from 4 August to 6 August.

Edgbaston Cricket Ground, Birmingham

Edgbaston Cricket Ground is a world leading cricket ground located in the Edgbaston area of Birmingham. Home to Warwickshire County Cricket Club's eight-time winning and reigning champion County Cricket team, its T20 team the Birmingham Bears, and the Birmingham Phoenix men's and women's teams in The Hundred competition, Edgbaston is also the venue for Test matches, One-Day Internationals, Twenty20 Internationals, and hosted the ICC Cricket World Cup in 2019. With permanent seating for approximately 25,000 spectators, it is the fourth-largest cricketing venue in England.[57] The South Stand (Pavilion), rebuilt in 2011 as part of the Edgbaston Stadium Masterplan, is a multi-tiered structure which holds the Press Box, hospitality suites, players changing rooms, administration offices, Visitor and Learning Centre, the Club shop and banqueting halls, with a seating capacity of over 4,000 spectators, while the Eric Hollies Stand, with a capacity of 5,900 seats, is traditionally the most raucous area of the ground. Edgbaston is reputed to generate the best atmosphere in England for visiting test cricket teams and the men's team's record is the best of any home ground in the country.[58]

In January 2021, work began on Phase 2 of Edgbaston's Stadium Masterplan, consisting of a new entrance plaza, car parking facilities and residential apartments, at a total cost of £93 million. In April 2021, the new Edgbaston Plaza was unveiled in time for the Games. It has a total area of 14,800 m2 (159,000 sq ft), making it one of the largest outdoor community spaces in Birmingham, and is designed to host cultural festivals and events as well as pre-and-post matchday crowds.[59][60]

Edgbaston will host the inaugural Commonwealth Games' Women's T20 cricket tournament between 29 July and 7 August.

Sutton Park, Birmingham

Sutton Park is an urban park located in the Royal Town of Sutton Coldfield, approximately 10 km (6.2 mi) north of Birmingham city centre. It is one of the largest urban parks in Europe, covering an area of around 2,400 acres (970 ha).[61] The park is a Scheduled Ancient Monument, a designated Site of Special Scientific Interest, and a national nature reserve, consisting of a mix of heathland, wetlands and marshes, seven lakes, and extensive ancient woodlands.

Amongst a range of annual sport events staged in the park, the City of Birmingham triathlon is traditionally held each July, with the open water swim stage taking place in Powell's Pool, the largest lake in the Park at 28 acres (11 ha).[62] Revealed on 27 October 2021, the course for the triathlon and para triathlon events at Birmingham 2022 is similarly designed, with the running leg taking place entirely within the park and the cycling section heading out through Boldmere Gate and onto the streets of Boldmere.[63] Inside the park, a ticketed spectator area will seat 500 amongst a total capacity of 2,000, while spectators for the non-ticketed cycling section of the event will be directed from Wylde Green station towards Boldmere, which is set to be adorned with Commonwealth Games related artwork courtesy of a £20,000 Creative Communities grant.[64]

University of Birmingham

The University of Birmingham is a public research university located in the Edgbaston district of Birmingham. Ranked amongst the world's Top 100 universities,[65] it is a founding member of both the Russell Group of British research universities and the international network of research universities, Universitas 21. It is the 7th largest university in the UK by student population. The university’s main campus, which occupies a site approximately 3 miles (4.8 km) south-west of Birmingham City Centre, is arranged around Joseph Chamberlain Memorial Clock Tower (affectionately known as 'Old Joe' or 'Big Joe'), a grand campanile which commemorates the university's first chancellor, Joseph Chamberlain,[66] and is a dominant feature on the Birmingham skyline. The main campus will be the venue for the squash and hockey events at Birmingham 2022,[67] while nearby Vale Village, a parkland site that normally accommodates 2,700 students, will be turned into one of the three separate Athletes’ Villages needed for the Games after plans for a single purpose-built village in Perry Barr were curtailed due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[68]

For the Games, two international-standard hockey pitches, built in 2017 as part of a £10 million outdoor facilities redevelopment, will be used to stage the field hockey competition. Temporary seating for around 6,000 spectators and accredited guests will be built around the main competition pitch, which has been re-carpeted in advance of the Games. In 2017, the University also opened a new £55 million Sport & Fitness Centre, comprising six squash courts with adjustable walls for larger doubles courts. For the squash competition, the 2,000 m2 (22,000 sq ft) indoor arena will house an all-glass court, featuring more than 2,000 seats for spectators and accredited guests.[69]

Victoria Square, Birmingham

On 27 October 2021, Victoria Square Birmingham City Centre was confirmed as the official finish area for the men’s marathon, women’s marathon and men’s and women’s T53/T54 wheelchair events. The pedestrianised square, which was formerly known as Council House Square, was renamed on 10 January 1901 to honour Queen Victoria, whose statue stands at its centre. The Square is surrounded by prominent buildings including the Town Hall on its western side, Birmingham Council House on its northern side, 130 Colmore Row to the east and Victoria Square House to the south. The square also features a cascading water fountain designed by Dhruva Mistry and officially unveiled by Diana, Princess of Wales in 1994, incorporating a 1.75-tonne bronze statue of a woman, 2.8 metres (9 ft) tall, 2.5 m (8 ft) wide and 4 m (13 ft) long, known locally as The Floozie in the Jacuzzi. In July 2015, the failing water works beneath the fountain led to the site being filled with bedding plants and ceasing to function as a water feature.[70] However, in 2021, work began on refurbishing the fountain to full working in order in time for the Games, and on 7 April 2022 the "Floozie" was returned to her fully functioning base.[71]

The marathon route which ends at Victoria Square consists of an 18 km (11 mi) loop which the athletes will complete twice, followed by a 6.2 km (3.9 mi) section around the City Centre. Starting at Smithfield, the athletes will head south out of the city, past Edgbaston Cricket Ground, into Cannon Hill Park, and complete a large loop around Stirchley and Bournville before returning to the City Centre via Selly Oak. The City Centre section of the route passes through by some of the city's most notable districts and sights, including the Chinese Quarter, Birmingham Gay Village, Hippodrome Theatre, Paradise, Centenary Square and the Library of Birmingham, before continuing north to the Jewellery Quarter and back into the City Core for the final kilometre of the route, passing by St Paul's on the way to Colmore Row, St Philip’s Cathedral, and the finish line at Victoria Square.[72] The looped section of the course follows a similar route to the Great Birmingham Run, an annual half marathon road running event held in Birmingham in October of each year as part of the United Kingdom's Great Run Series.

On 4 March 2022 it was reported that the statue of Queen Victoria in the square would be temporarily "dressed" by Guyanese-British sculptor Hew Locke for the duration of the Games, as part of the Birmingham 2022 Festival cultural programme which will launch on 14 June. A planning application for the project, entitled Foreign Exchange, was submitted to Birmingham City Council on 20 May 2022. The proposed wrap-around features a two-tonne fibreglass boat 6.8 m (22 ft) metres long and 2.3 m (8 ft) metres wide, containing several "perspectives" of the Queen. The proposal, described as a "temporary intervention", has caused controversy in some quarters, with the Save Our Statues campaign calling the project “cultural vandalism”.[73][74]

Cannock Chase Forest, Cannock Chase

Cannock Chase, known locally as The Chase, is a mixed area of countryside in the county of Staffordshire, approximately 35 km (22 mi) north of central Birmingham. It is a former Royal forest and a designated Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The area of The Chase known as Birches Valley is a popular destination for cross-country mountain bikers, with trails including the technically-challenging 12 km (7.5 mi) XC Follow the Dog trail[75] and the 11.2 km (7.0 mi) Monkey Trail.

On 21 May 2022, new facilities were officially unveiled in readiness for the Games, including Perry’s Trail, an off-road blue-graded trail developed by Forestry England, which will form the backbone of the course for the men's and women's mountain bike competition, and a bike play trail called Pedal and Play, which was designed in partnership with British Cycling to inspire the next generation of mountain bikers. Funding for the £1 million legacy project was secured from partners including Sport England, British Cycling, Cannock Chase District Council and Staffordshire County Council.[76][77]

Coventry Stadium and Arena

Coventry Stadium and Arena is a sport and leisure complex in Coventry, incorporating a 32,609-seater stadium, a 6,000 m2 (65,000 sq ft) arena and exhibition space, a hotel with pitch-side views,[78] a casino,[79] a 400 m2 (4,300 sq ft) sports bar,[80] and a retail centre. The Stadium is home to rugby union club Wasps, who took ownership of the facility in 2014,[81][82] and Championship football club Coventry City F.C., for whom the stadium was originally designed.[83] since its opening in 2005, the stadium has played host to England under-21 and England under-19 internationals,[84] the Women's FA Cup final,[85] Rugby World Cup warm-up matches, 2016 Rugby League Four Nations[86] domestic Rugby League[87] and American football fixtures,[88] as well as 12 tournament matches at the London 2012 Olympics, while the indoor Arena, which has been home to Netball Superleague side Wasps Netball since February 2017, has also staged Davis Cup Tennis,[89] Champion of Champions snooker,[90] and Darts.[91][92]

Coventry Stadium is sponsored by Coventry Building Society, which entered into a ten-year naming rights deal in 2021, taking over from previous sponsor Ricoh,[93] although for the duration of the Commonwealth Games it will be known simply as Coventry Stadium. It will host the Rugby Sevens tournament from 29 to 31 July 2022.

The adjacent Arena, otherwise known as the Ericsson Exhibition Hall,[94] will host the judo competition from 1 to 3 August and the wrestling from 5 to 6 August 2022.

Myton Fields, Warwick

On 30 September 2020 it was announced that the Men’s and Women’s Cycle Road Race would be staged in and around Warwick. Warwick is a market town, civil parish and the county town of Warwickshire on the banks of the River Avon, located 9 miles (14 km) south of Coventry and 19 miles (31 km) south-east of Birmingham, and forming part of a contiguous conurbation of some 95,000 inhabitants with its larger neighbour Leamington Spa, and the town of Whitnash.[95] Warwick was a major fortified settlement from the early Medieval period, the most notable relic of this era being Warwick Castle, founded by William the Conqueror in 1068 and now a major tourist attraction. The town also has an array of historic buildings from the Stuart and Georgian eras. When the hosting decision was announced, Chairman for Birmingham 2022, John Crabtree, said holding the cycling competitions in Warwickshire would increase the Games’ regional reach and the area's picturesque backdrops would help showcase the “rich and varied landscape that the West Midlands has to offer.”[96]

Warwickshire has a history of staging high-level cycling events, having played host to a stage of The Women's Tour for four years and, subsequently, the Tour of Britain in 2018 and 2019, the latter of which consisted of an uphill stage from Warwick Town Centre to Burton Dassett Country Park.[97] In 2021, Atherstone in North Warwickshire staged the first ever Women’s Tour time trial.[98]

Initially, the location for the start and finish of the Birmingham 2022 race was reported to be St. Nicholas’ Park, known locally as St. Nick’s, a popular 40 acres (16 ha) urban park and former meadow land at the southern edge of the town, situated close to Warwick railway station. However, the official start point was later confirmed to be Myton Road at the entrance to Myton Fields, an open grass area on the opposite side of the river to St Nicholas Park, which is sometimes used as an overflow car park and will act as the muster point for the riders prior to the start of the race.

On 27 October 2021, the full route for the race was revealed: a 16 km (9.9 mi) circuit around Warwick and the surrounding area which the men will complete ten times (160 km (99 mi)) and the women seven times (112 km (70 mi)). Starting on Myton Road, the course heads north over the River Avon towards the town centre, taking in views of Warwick Castle and St Nicholas' Park, before turning left onto Jury Street, past the Collegiate Church of St Marys, Warwick Town Council’s offices, and then onto Warwick High Street, passing by Lord Leycester Hospital on the right. The course follows this road until turning right onto Shakespeare Avenue, before turning left opposite Warwick Racecourse. The cyclists will then head out through the village of Hampton on the Hill and onto the rural section of the course, before looping back towards Warwick via Victoria Park in Royal Leamington Spa, which is hosting the Birmingham 2022 Lawn Bowls and Para Lawn Bowls competition. The final part of the course crosses back over the River Avon, turning right at the roundabout and onto a long straight run down Myton Road, passing by Warwick School and Myton Fields en route to the finish line.[99] The route was described by Warwickshire County Councillor Heather Timms as a “challenging course” that “showcases the historic splendour of the town of Warwick”.[100]

The Cycling Road Race is one of the Games’ five ticketless events and up to 15,000 local people and visitors are expected to line the route on Sunday 7 August 2022.

National Exhibition Centre (NEC), Solihull

The National Exhibition Centre (NEC) is an exhibition centre located in Marston Green in the metropolitan borough of Solihull, 19 km (12 mi) from Birmingham City Centre. Opened by Queen Elizabeth II in 1976, and extended in phases between 1989 and 1998,[101][102] the NEC is the UK’s largest exhibition venue and one of Europe’s leading event destinations, its 20 interconnected halls covering 190,000 m2 (2,000,000 sq ft) of floor space.[103] It hosts around 500 events each year, attracting 45,000 exhibiting companies and 2.3 million visitors.[104] The venue is owned and operated by parent company the NEC Group, which also owns and operates Arena Birmingham and NEC Arena ICC Birmingham, as well as the NEC Arena.

The NEC’s largest exhibition halls will host four sports and two para sports at Birmingham 2022: Weightlifting and Para Powerlifting in Hall 1; Table Tennis and Para Table Tennis in Hall 3; Boxing in Hall 4; and Badminton in Hall 5. The complex will also host a fan park for ticketed spectators, which is anticipated to include giant screens, live commentaries, on-site interviews and a range of cultural performances, along with Have a Go sessions for fans to try out new sports.[104][105]

The NEC is situated adjacent to Birmingham Airport and is served by Birmingham International railway station, to which it is physically connected, along with local bus services.[106] It also sits at the heart of the UK’s road network, and provides 16,500 parking spaces spread around the site, with a free shuttle bus service operating between them.[107] However, Birmingham 2022 have stated that road restrictions will be in operation during the Games and on-site parking will only be bookable in advance, so it is not clear how straightforward it will be to drive to the NEC during this period. [104]

NEC Arena, Solihull

The NEC Arena is a multipurpose indoor arena located at the National Exhibition Centre (NEC) in Solihull, with a seating capacity of 15,685.[45] It was built as the seventh hall of the NEC complex and opened in 1980.[108] Operated by the NEC Group, the venue is currently sponsored by Genting UK as part of its Resorts World brand, but for Birmingham 2022 will simply be known as the NEC Arena. It will host the women's netball competition between 29 July and 7 August 2022.[109]

On 9 March 2020, the NEC Group submitted planning permission to Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council to expand the capacity of arena from 15,685 to 21,600, which would make it the largest indoor arena in the United Kingdom. This development would involve the demolition of the existing roof and addition of an upper tier, as well as other works including enhanced hospitality facilities, and external, internal and major refurbishment works.[110] The application was approved on 28 May 2020.[111] However, in June 2020, the NEC Group announced that the redevelopment work would not occur until after Birmingham 2022 due to the ongoing disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.[112]

Victoria Park, Royal Leamington Spa

Victoria Park will host the Lawn Bowls and Para Lawn Bowls events at Birmingham 2022, with up to 5,000 spectators per day expected to attend.[113] The riverside park's five bowling greens are amongst the best in England, hosting the English Men's and Women's Bowling Championships annually as well as the Women's World Bowling Championships in 1996 and 2004.[114][115]

As part of Warwick District Council's Commonwealth Games project, the venue has undergone a programme of improvements in advance of the event including upgraded playing surfaces for each of the greens, and redevelopment and refurbishment of the Bowls Pavilion and Clubhouse, incorporating enhanced Wi-Fi provision and a new PA system. These upgrades are the focus of a £1.8 million programme of infrastructural and landscaping improvements in and around Victoria Park and Leamington Spa railway station in preparation for hosting the Games.[116][117]

West Park, Wolverhampton

West Park is a 43 acres (17 ha) urban park located on the north-western edge of Wolverhampton city centre, close to the University of Wolverhampton City Campus and Molineux Stadium. It was opened as the People's Park on 6 June 1881 by then Mayor of Wolverhampton, Alderman John Jones and, following the restoration of its period structures including the conservatory, clock tower and lakeside pavilion, is one of the best preserved examples of a Victorian park in England.[118]

West Park will be the venue for the start and finish of the cycling time trials for Birmingham 2022. Ian Reid, CEO of Birmingham 2022, said Wolverhampton was the perfect setting for the time trials, as there was plenty of space and incredible support for cycling around the city, and that it was vital to bring the games to the whole of the West Midlands.[119]

The 37 km (23 mi) Men’s Time Trial route will depart West Park and wind through Wolverhampton City Centre, passing by the Wolverhampton City Council offices, St Peters Church, Queen Square, and the Church of St John in the Square, before heading south into Dudley town centre via Sedgley. The course passes close to Dudley Castle and Dudley Zoo, Coronation Gardens, the Dudley Metropolitan Borough Council building and Dudley Town Hall, before heading back towards Sedgley via the biggest climb on the course at Moden Hill. The cyclists will then head through Gornalwood and into South Staffordshire, passing Himley Hall on route to the villages of Himley, Wombourne and Gospel End. The final section of the course takes the cyclists across Penn Common and back into Wolverhampton city centre, passing Market Square, before finishing back in West Park.

The Women’s circuit, being 8 km (5.0 mi) shorter than the Men’s, will not take in the section through Gornalwood and Himley.[120]

Lee Valley VeloPark, London

Lee Valley VeloPark is a cycling centre at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in Stratford, East London, owned and managed by Lee Valley Regional Park Authority. The facility was one of the permanent venues for the 2012 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games. Construction of the park’s flagship Velodrome was completed in 2011 at an estimated cost of £105 million[121] and was used for the first time in competition during the UCI Track Cycling World Cup in February 2012. Since London 2012, it has staged the Revolution series, the UCI Track Cycling World Cup and the 2016 UCI Track Cycling World Championships.[122][123][124][125] The Velodrome, known informally as "The Pringle" due to its distinctive shape, was shortlisted for the 2011 RIBA Stirling Prize[126] and in the same year won both the Structural Awards Supreme Award for Structural Engineering and the Prime Minister's Better Public Building Award at the British Construction Industry Awards.[127] It has a seated capacity of 6,750.

The decision to stage the track cycling at Lee Valley was a controversial one, given its distance of 136 miles (218 km) from the Games’ host city. The Birmingham bid committee had investigated using the Derby Arena in Derby or converting the Arena Birmingham into a temporary velodrome, but both options were ruled out as they failed to meet the minimum venue seating capacity of 4,000 set out by the Commonwealth Games Federation. On the day of the host city announcement, the Games’ organising committee confirmed that the track cycling events would instead be held in London.[128][129] A petition was launched by members of the public calling for a velodrome to be constructed in the West Midlands,[130] but the decision was defended by Birmingham City Council, claiming it was reached in consultation with British Cycling and Sport England and suggesting that a new velodrome, which would cost £50 million to construct, would make staging the entire Games an unviable proposition.[131][132] In March 2020, British Cycling issued a "Cycling Facility Assessment" which stated that building a new velodrome in Birmingham was not considered a “high priority” and did not have an adequately stable strategic or business case to support such an investment.[133] For those who signed the petition, the decision was seen as a lost opportunity to help develop the sport in a region with a population of 5.6 million people but no dedicated track cycling venue.

The track cycling programme, consisting of the Sprint/Para-Sport Tandem Sprint, Time Trial, Individual and Team Pursuit, Scratch Race, Points Race, Team Sprint and Keirin, will take place in the Lee Valley Velodrome from 29 July to 1 August 2022.

Change in venues

The Birmingham Organising Committee changed the venues of netball and rugby sevens events. The netball was moved from the Coventry Arena in Coventry to the National Exhibition Centre in Solihull and the rugby sevens was moved from Villa Park in Birmingham to the Coventry Arena. The former venues of those sporting events were decided during the preparation of the Birmingham bid in 2017 and the latter venues were decided in September 2019.[134]

Live Festival Sites

In addition to the competition venues, a network of Birmingham 2022 Festival Sites will be established for the duration of the Games. These free-to-enter sites will feature big screens broadcasting live event coverage, concerts, parties, food, beverages, cultural activities and other entertainment.

City of Birmingham

On Friday 10 June, it was confirmed that Birmingham City Centre will host two live Festival Sites, one at Victoria Square and the other at Smithfield. The Victoria Square site will throw ‘watch parties’ for the Opening and Closing Ceremonies, while Smithfield will host a dance party finale. Both sites will offer a full schedule of event broadcasts and live entertainment throughout the Games.[135]

The two City Centre sites will be complemented by seven Birmingham Neighbourhood Festival Sites, intended to give residents across the city an opportunity to “celebrate and embrace the Games” in their local areas. The site locations, announced on 9 February 2022, will be Farnborough Fields, Castle Vale; Edgbaston Reservoir; Handsworth Park; Selly Oak; Sparkhill Park; Ward End Park; and Oaklands Recreation Ground, Yardley. The Selly Oak site will be hosted by Sense Touchbase Pears and will be the Games’ first ever fully Relaxed Festival Site, catering for deafblind people and those with complex needs. It will provide quiet areas, dimmed lighting, audio descriptions, and specialist communicators including British Sign Language interpreters.[135][136][137]

West Midlands Region

Nine cities and towns across the West Midlands region will also host live Festival Sites for the Games. Seven of the sites will be in locations which already have competition venues and will be managed by the local authorities in those areas: The Assembly Festival Garden in Coventry, adjacent to Coventry Council House; The Pump Room Gardens in Leamington Spa; Market Square in Warwick; Sandwell Valley Showground in Sandwell; Mell Square and Theatre Square, Touchwood in Solihull; and Market Square in Wolverhampton. Dudley will host a daily roadshow taking in the following venues: Huntingtree Park in Halesowen; Silver Jubilee Park in Coseley; Mary Stevens Park in Stourbridge; The Dell Stadium in Brierley Hill, Netherton Park in Netherton; and Stevens Park in Quarry Bank.[135]

Two further live Festival Sites will be established in towns that are not hosting Games events: The Castle Grounds in Tamworth, Staffordshire, and Southwater in Telford, Shropshire.[135]

South East

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in Stratford, East London, will host the ‘Celebrating 10 Years’ Festival Site, delivered in partnership between Birmingham 2022, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and the London Legacy Development Corporation.[135]

Gallery

Alexander Stadium (undergoing renovation)

Alexander Stadium (undergoing renovation)

.jpg.webp)

Smithfield (under construction)

Smithfield (under construction)

.jpg.webp)

Lee Valley VeloPark Velodrome (London)

Lee Valley VeloPark Velodrome (London)

References

- ↑ "The venues hosting the games across Birmingham and West Midlands". B2022. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ↑ "About Alexander Stadium". Birmingham2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ "About Arena Birmingham". Birmingham2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ "About Edgbaston Stadium". Birmingham2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ "About Smithfield". Birmingham2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ "About Sutton Park". Birmingham2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ "About the University of Birmingham". Birmingham2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ "About Victoria Square". Birmingham2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ "About Cannock Chase Forest". Birmingham2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ "About Coventry Arena". Birmingham2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ "About Victoria Park". Birmingham2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ "About Sandwell Aquatics Centre". Birmingham2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- 1 2 "About The NEC". Birmingham2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ "About Warwick". Birmingham2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ "About West Park". Birmingham2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ "About Lee Valley Velopark". Birmingham2022. Retrieved 29 May 2022.

- ↑ Alexander, William O; Morgan, Wilfred (1988). The History of Birchfield Harriers 1877–1988. Birchfield Harriers. ISBN 0-9514082-0-8.

- ↑ "Alexander Stadium's bid to be UK Athletics base". BBC. 22 September 2010. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- ↑ "UK Athletics heading for a grandstand view of the Alexander Stadium". Inside the Games. 15 July 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2011.

- ↑ "Birmingham 2022 in talks with Diamond League over Commonwealth Games test event". www.insidethegames.biz. 30 November 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ↑ "English schools 2019". ESAA.

- ↑ "Stadium expansion at heart of 2022 bid". BBC News. 20 June 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games 2022: Liverpool & Birmingham should use London Stadium - Ed Warner". BBC Sport. 13 August 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ↑ "PM announces £70 million to transform Birmingham stadium for 2022 Commonwealth Games". GOV.UK. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ↑ Marshall2018-10-25T09:39:00+01:00, Jordan. "Arup wins design contract for £70m revamp of Commonwealth Games stadium". Building. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Mace to project manage Birmingham Commonwealth Games stadium". Infrastructure Intelligence. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ↑ Dare, Tom (18 February 2019). "Alexander Stadium will be £75m white elephant, claim". birminghammail. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- ↑ "Alexander Stadium will be £75m white elephant, claim". Genesis Radio Birmingham. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ↑ "Birmingham targets taking athletics off London as £70 million Alexander Stadium redevelopment plan for 2022 Commonwealth Games unveiled". www.insidethegames.biz. 21 June 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ↑ "Alexander Stadium revamp gets green light". AW. 30 January 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- 1 2 "Commonwealth Games stadium revamp approved". BBC News. 30 January 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- 1 2 "Birmingham approves proposals for Alexander Stadium redevelopment". Verdict Designbuild. 31 January 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ↑ Rogers2020-03-13T06:00:00+00:00, Dave. "Winner emerges on 2022 Commonwealth Games stadium". Building. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Council, Birmingham City. "Alexander Stadium development". www.birmingham.gov.uk. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ↑ "Alexander Stadium revamp plans approved ahead of Commonwealth Games". ITV News. 30 January 2020. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ↑ "Alexander Stadium revamp gets green light". AW. 30 January 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ↑ "Dina Asher-Smith beats Shericka Jackson to win Birmingham Diamond League 100m". bbc.co.uk. 21 May 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ↑ Skipp, Victor (1987). "The Town in the 1820s". The History of Greater Birmingham – down to 1830. Yardley, Birmingham: V. H. T. Skipp. p. 85. ISBN 0-9506998-0-2.

- ↑ "PHOTOGRAPHY AS ART AND SOCIAL HISTORY". Adam Matthew Publications. Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ Hutton, William (1836). The History of Birmingham. J. Guest. pp. 62. ISBN 9780854096220.

- ↑ "Markets: Wholesale Markets History". Birmingham City Council. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 11 May 2007.

- ↑ Brazendale, Sarah (24 March 2022). "See how Smithfield Birmingham is set to transform the heart of the city". BirminghamLive. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ↑ "Smithfield - Former Smithfield Market Site, Birmingham". birmingham2022.com. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ↑ "Festival Sites". birmingham2022.com. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Major Construction Work at the Sandwell Aquatics Centre Site". Commonwealth Games Committee. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ↑ "Birmingham 2022: Aquatics centre will 'inspire new generation'". BBC News. 16 January 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ↑ "Wates appointed to deliver Sandwell Aquatic Centre". Wates. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ↑ "Wates appointed as main contractor to build Sandwell Aquatics Centre". Wates. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ↑ "First look at the new Sandwell Aquatics Centre ahead of the Birmingham 2022 Games". Birmingham Mail. 10 February 2021. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ↑ "Sandwell Aquatics Centre | Sandwell Council". www.sandwell.gov.uk. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ↑ "Sandwell Aquatics Centre". Sandwell Borough Council. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- ↑ "Venue Information". Barclaycard Arena. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ "Our brands". NEC Group. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ "About Arena Birmingham". Birmingham 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "International firm awarded £24m contract to refurbish Birmingham NIA". Birmingham Post. Birmingham. 16 May 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ↑ "Arena Birmingham to change name again - and everyone says same thing". 16 January 2020.

- ↑ Barnett, Rob (10 August 2011). "Edgbaston at the cutting edge". England and Wales Cricket Board. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ↑ Weaver, Paul (29 July 2009). "If Australia thought Cardiff and Lord's was noisy, they haven't heard anything yet". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media. p. 4. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ↑ "Works begin on £93 million Phase 2 of the Edgbaston Stadium Masterplan". Invest West Midlands. 13 January 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ↑ Rawlings, Tom (11 April 2022). "Edgbaston Stadium unveils new plaza, one of the largest outdoor community spaces in Birmingham". Edgbaston. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ↑ "About the park". Birmingham City Council. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "Birmingham Triathlon". British Triathlon. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "Birmingham 2022 confirms triathlon course". British Triathlon. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ Cardwell, Mark (19 August 2021). "How the Commonwealth Games will totally change Sutton Park to cater for 2,000 spectators". Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "International rankings". Birmingham.ac.uk. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ↑ Crosby, Travis L. (2011). Joseph Chamberlain: A Most Radical Imperialist. I.B.Tauris. p. 236. ISBN 9781848857537. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ↑ "Official Partner of the Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games". www.birmingham.ac.uk. University of Birmingham. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ↑ Cardwell, Mark (3 February 2022). "Official Athletes village to be put up around University of Birmingham student halls for Commonwealth Games". www.birminghammail.co.uk. BirminghamLive. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ↑ "University of Birmingham Hockey and Squash Centre". Birmingham 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ↑ Cannon, Matt (6 July 2015). "Birmingham's Floozie fountain swaps Jacuzzi for flowerbed - Birmingham Mail". Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ↑ Young, Graham (7 April 2022). "Floozie in the Jacuzzi returns to Birmingham - but uncertainty remains over fountain reopening - Birmingham Live". Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ↑ "Marathon: About The Course". Birmingham 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ Cardwell, Mark (4 March 2022). "Famous statue of Queen Victoria in Birmingham set to be 'dressed' by artist". Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "2022/03740/PA 1 Victoria Square, Birmingham, B1 1BD". 20 May 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "'Follow the Dog' trail". Chasetrails.co.uk. 26 March 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- ↑ "Funding approved to create new Cannock Chase bike trails ahead of Commonwealth Games". Express & Star. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "New cycling facilities open at Cannock Chase Forest ahead of Birmingham 2022". Birmingham 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "Coventry Accommodation at The Ricoh Arena Hotel". Retrieved 31 October 2016.

- ↑ "G Casino – Ricoh Arena". Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ↑ "State-of-the-art Sports Bar Set To Open At Ricoh Arena". www.ricoharena.com. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ↑ "Ricoh Stadium Move". Wasps RFC. Wasps RFC. 8 October 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ↑ "Wasps Confirm 100% Shareholding In The Ricoh Arena". Wasps RFC. Wasps RFC. 14 November 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ Shoesmith, Ian (28 April 2012). "Why are Coventry City at their lowest ebb for nearly 50 years?". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- ↑ "England Matches – Under-19's 1991–2010". Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ↑ "BBC Sport – Women's FA Cup final: Arsenal 2–0 Bristol Academy". BBC Sport. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ↑ McCartney, Aidan (22 April 2016). "Rugby League's Four Nations internationals heading to Coventry".

- ↑ "Ricoh Arena set to host first ever rugby league clash as Coventry Bears take on Keighley Cougars".

- ↑ "Welcome to the Cassidy Jets Website! – News". 4 October 2011. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011.

- ↑ "Ricoh Arena set to host Great Britain Davis Cup tie". Coventry Observer. 31 January 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ↑ "Ricoh to host Champion of Champions snooker". Coventry Telegraph. 2 May 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

- ↑ "Planet Darts – Tournaments – Whyte & Mackay Premier League Darts – Whyte & Mackay Premier League Darts – Premier League Darts – Night Three". Archived from the original on 22 February 2009. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ↑ Rodger, James (5 September 2014). "Darts greats set for Ricoh Arena show". Coventry Telegraph. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ↑ "Wasps stadium to become Coventry Building Society Arena in naming rights deal". ITV News. 5 May 2021. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ↑ Campelli, Matthew (4 August 2016). "Ricoh Arena Exhibition Hall renamed following technology deal with Ericsson | Leisure Opportunities news". www.leisureopportunities.co.uk. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ↑ "United Kingdom: Urban Areas in England". City Population. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ↑ "Great news for cycling in Warwickshire as Warwick confirmed as host for Birmingham 2022 cycling road race". Warwickshire County Council. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ↑ "Warwickshire to host first-ever women's tour time trial". The Woman’s Tour. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ↑ "Tour of Britain: Welcome to Warwickshire – the 'Spectator Stage'". Warwickshire County Council. 18 March 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ↑ "Cycling Road Race: About The Route". Birmingham 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ↑ "Tour of Britain: Welcome to Warwickshire – the 'Spectator Stage'". Warwickshire District Council. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ↑ "National Exhibition Centre celebrates 40th birthday". Birmingham Live. 15 June 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ↑ "National Exhibition Centre". New Civil Engineer. 29 January 1998. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ↑ "NEC widens its window on the world". The Guardian. 19 February 2001. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- 1 2 3 "The NEC". Birmingham 2022. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ↑ "Birmingham Weekender encapsulates spirit of cultural programme for 2022 bid". Birmingham City Council. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ↑ "All About - NEC Birmingham - Birmingham Live". www.birminghammail.co.uk. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ↑ "Car Parking". thenec.co.uk.

- ↑ "NEC: From Eurovision to the G8". 5 March 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- ↑ "Birmingham 2022 unveils netball match schedule". England Netball. 12 November 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "Plans to expand major arena submitted". Insider Media Ltd. 5 March 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ↑ "Planning – Application Summary PL/2020/00504/PPFL". Solihull Council. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "Resorts World Arena expansion put on hold until after Commonwealth Games". The Stadium Business. 2 June 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- ↑ "About Victoria Park". Birmingham 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "Bowling greens". Warwick District Council. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ↑ "Event History". World Bowls Championship Christchurch NZ 2008. 2008. Retrieved 13 July 2008.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games 2022 project". Warwick District Council. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "Royal Leamington Spa's Victoria Park proposed improvements". Warwick District Council. Retrieved 24 May 2022.

- ↑ "West Park". 11 June 2015.

- ↑ "Wolverhampton to host 2022 Commonwealth Games cycling time trial".

- ↑ "Cycling Time Trial".

- ↑ "Velodrome for 2012 Games opened". BBC News. 22 February 2011.

- ↑ "Sport On The Box » UCI Track World Cup London 2014 on BBC Sport". Archived from the original on 8 December 2014.

- ↑ "London to host 2014 UCI Track Cycling World Cup - UCI Track Cycling World Cup London". Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ "Track World Cup: GB name five Olympic champions for London - BBC Sport". BBC Sport.

- ↑ "Revolution Series 2014/15, round one: Laura Trott off to a flyer against Marianne Vos at Lee Valley VeloPark". Daily Telegraph. 26 October 2014.

- ↑ Waters, Florence (21 July 2011). "RIBA Stirling Prize shortlist 2011: Olympic 'Pringle' Velodrome – Velodrome favourite for best new building in Europe – The Velodrome, an intimate cycling arena in London's Olympic Park, has been shortlisted for Britain's most coveted architecture award". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ↑ "Winners 2011". bciawards.org.uk. 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ "London to host track cycling at 2022 Commonwealth Games". www.insidethegames.biz. 21 December 2017. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ↑ Elkes, Neil (21 December 2017). "Birmingham 2022 track cycling will be held 130 miles away - here's why". birminghammail. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "Petition urging velodrome to be built in West Midlands for 2022 Commonwealth Games launched". www.insidethegames.biz. 27 January 2018. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ↑ Dare, Tom (24 August 2018). "2022 Games velodrome ruled out due to 'study' that never existed". birminghammail. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ↑ "Process to choose velodrome for Birmingham 2022 defended by organisers". www.insidethegames.biz. 1 September 2018. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- ↑ "Birmingham velodrome proposal did not have sufficient case for investment". www.insidethegames.biz. 21 March 2020. Archived from the original on 18 May 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ↑ "Birmingham 2022 move netball from Coventry to NEC to cash in on popularity". www.insidethegames.biz. 3 September 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Birmingham 2022 announce major city centre Festival Sites for this summer's Commonwealth Games". birmingham2022.com. 10 June 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ↑ "Commonwealth Games festivals planned where you can watch Birmingham 2022 for free". birminghammail.co.uk. 9 February 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ↑ "Relaxed screening of the Birmingham 2022 Commonwealth Games opening ceremony". sense.org.uk. Retrieved 13 June 2022.