|

|---|

|

|

| History of New Zealand |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| General topics |

| Prior to 1800 |

| 19th century |

| Stages of independence |

| World Wars |

| Post-war and contemporary history |

|

| See also |

|

|

Voting in New Zealand was introduced after colonisation by British settlers. The first New Zealand Constitution Act was passed in 1852, and the first parliamentary elections were held the following year.[1]

Between 1853 and 1876, elections were held five years apart. In the mid-19th century, provincial council elections attracted more press attention, more candidates and more voters than general elections; the provincial councils were abolished in 1876.[2] Since 1879, elections have typically been held every three years. In times of crisis such as wars or earthquakes, elections have been delayed, and governments have occasionally called early ('snap') elections.[1] Because the New Zealand system of government is relatively centralised, today most electoral and political attention is focused on general elections rather than local elections (which are also held at three-year intervals).[1]

Until 1879 only male property owners could vote in general electorates, which meant that a disproportionate number of electors lived in the countryside. However, Māori electorates were created in 1867, in which all Māori men could vote. Women were enfranchised in 1893, establishing universal suffrage. The introduction of the mixed-member proportional (MMP) system in 1996 provides that all votes contribute to the election result, not just a plurality.

While voter turnout is relatively high by international democratic standards,[3] trends in New Zealand show a general decline since the 1960s,[4] although turnout increased over the last four general elections (2011, 2014, 2017 and 2020).

Early local body elections

The first notable election held in the new colony was the election of the first Wellington Town council pursuant to the Municipal Corporations Act in October 1842.[5] It was open to all "Burgessers". These were undoubtedly male only, though it is not clear whether it was only Europeans who were permitted to vote and what age restrictions applied. There was a one-pound poll tax, rather than a property requirement. This led to accusations of vote buying by those wealthy enough to pay for the registration of indigent electors, however the practice was so prevalent all those candidates who were ultimately successful used the tactic. In contrast to later national elections this local election also saw the emergence of a nascent working class party under the auspices of the Working Men's Association and the Mechanic's Institute.

Voting following the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852

The first national elections in New Zealand took place in 1853, the year after the British government passed the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852. This measure granted limited self-rule to the settlers in New Zealand, who had grown increasingly frustrated with the colonial authorities (and particularly with the nearly unlimited power of the Governor). The Constitution Act established a bicameral parliament, with the lower house (the House of Representatives) to be elected every five years. The upper House (the appointed Legislative Council) was later abolished in 1950.[1]

Initially, the standards for suffrage were relatively high. To vote, a person needed to be:[6]

- male,

- a British subject,

- aged at least 21 years old,

- an owner of land worth at least £50, or payer of a certain amount in yearly rental (£10 for farmland or a city house, or £5 for a rural house); and,

- not be serving a criminal sentence for treason, for a felony, or for another serious offence.

In theory, this would have allowed Māori men to vote, but electoral regulations excluded communally-held land from counting towards the property qualification (quite a common restriction in electoral systems of the time). In these circumstances, many Māori (most of whom lived in accordance with traditional customs of land-ownership) could not vote. Historians debate whether or not the system deliberately excluded Māori in this way. There was concern amongst many settlers that the "uncivilized" Māori would be, if enfranchised, a voting bloc with the numerical strength to outvote Europeans. However, most Māori had little interest in a "settler parliament" that they saw as having little relevance to them.

Despite the exclusion of Māori and of women, New Zealand's voting franchise appeared highly liberal when compared to that of many other countries at the time. At the time of the passing of the Constitution Act, an estimated three-quarters of the adult male European population in New Zealand had the right to vote. This contrasts with the situation in Britain, where the equivalent figure approximated to a fifth of the adult male population.

Supplementary elections

Due to the rapidly expanding settler population, several changes were made to electoral boundaries and supplementary elections were held during the terms of the second, third and fourth parliaments, including those elections that extended the franchise to gold miners and Māori.

Key developments for voting in New Zealand

Gold miners and the vote

In 1860, 15 additional electorates were created.[7] An electoral redistribution in 1862[8] took account of the influx of people to Otago because of the Central Otago gold-rush, which began in 1861. In 1862 the franchise was extended to males aged 21 years and over who had held a miner's right continuously for at least three (or six) months. This aimed to enfranchise miners even if they did not own or lease land, as they were nevertheless ranked as "important" economically and socially.

A special multi-member electorate was created in Otago, the Goldfields electorate 1863–70, and then the single-member Goldfields Towns electorate 1866–70. To vote, a miner just presented his miner's licence to the election official, as there were no electoral rolls for these electorates. Outside Otago, where no special goldfields electorate(s) existed, miners could register as electors in the ordinary electoral district where they lived. There were an estimated 6000 holders of miner's licences.

Creation of Māori electorates

1867 saw the establishment of four Māori electorates, enabling Māori to vote without needing to meet the property requirements. Supporters of this change intended the measure as a temporary solution, as a general belief existed that Māori would soon abandon traditional customs governing land ownership. Soon, however, the seats became an electoral fixture. While some have seen the establishment of Māori electorates as an example of progressive legislation, the effect did not always prove as satisfactory as expected. While the seats did increase Māori participation in politics, the relative size of the Māori population of the time vis à vis Pākehā would have warranted approximately 15 seats, not four. Because Māori could vote only in Māori electorates, and the number of Māori electorates remained fixed for over a century, Māori stayed effectively locked into under-representation for decades.

With the introduction of MMP in the 1990s, there were calls to abolish the four Māori electorates as Māori and Pākehā alike would vote in the same party vote, and all parties above 5% would be in Parliament (leading some to argue proportional representation of Māori would be inevitable). However these calls were shot down by Māori leaders and instead the number of seats was increased to better represent the population. In 2002, the number of Māori electorates was increased to seven, where it has stayed ever since.[6]

In recent history, a number of people have continued to call for the abolition of the seats, including Winston Peters, the leader of NZ First party.[9]

Municipal suffrage for women ratepayers

In 1867, with the passing of the Municipal Corporations Act,[10] parliamentary members admitted in debates that it contained no provision to prevent women from voting at the local level. Woman suffrage was made optional in the Act, but only Nelson and Otago Provinces allowed it in practice.[11] It was made compulsory in all provinces in 1875. An 1867 editorial in the Nelson Evening Mail explained:

- "... They are ratepayers, and as such are electors for parochial purposes, and may even serve as guardians, they are also taxpayers, but are neither permitted to vote the supplies nor to elect these who do vote them. Moreover the exclusion of women from Parliamentary rights is an infringement of the primary law of constitutional government that there should be no taxation without representation."[12]

Introduction of the secret ballot

Initially, voters informed a polling officer orally of their chosen candidate. The secret ballot, whereby each voter marks their choice on a printed ballot and places the ballot in a sealed box, has been used by European New Zealanders since the 1871 election[13] and for Māori seats since 1938.[14] The change occurred to reduce the chances of voters feeling intimidated, embarrassed, or pressured about their vote, and to reduce the chances of corruption.[13]

Abolition of the property requirement

After considerable controversy, Parliament decided in 1879 to remove the requirement of property ownership.[15] This allowed anyone who met the other qualifications to participate in the electoral process. As the restrictions on suffrage in New Zealand excluded fewer voters than in many other countries, this change did not have the same effect as it would have had in (for example) Britain, but it nevertheless proved significant. In particular, it eventually gave rise to "working class" politicians, and eventually (in 1916) to the Labour Party.

Country quota

Established in 1881, the country quota required rural electorates to be around a third smaller than urban electorates, thus making rural votes more powerful in general elections. The quota was later abolished by the first Labour government in 1945.

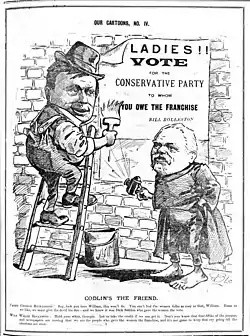

Women's suffrage

New Zealand women finally gained the right to vote in national elections with the passage of a bill by the Legislative Council in 1893. The House of Representatives (then the elected lower house) had passed such a bill several times previously, but for the first time in 1893 the appointed Legislative Council did not block it.

The growth of women's suffrage in New Zealand largely resulted from the broad political movement led by Kate Sheppard, the country's most famous suffragette. Inside parliament, politicians such as John Hall, Robert Stout, Julius Vogel, William Fox, and John Ballance supported the movement. When Ballance became Premier in 1891 and established/consolidated the Liberal Party, many believed that female suffrage would ensue imminently, but attempts to pass a suffrage bill repeatedly met with blocks in the Legislative Council, which Ballance's outgoing predecessor, Harry Atkinson, had stacked with conservative politicians.

When Ballance suddenly died in office on 27 April 1893, Richard Seddon replaced him as Premier. Seddon, though a member of Ballance's Liberal Party, opposed women's suffrage, and expected it to be again blocked in the upper house. Despite Seddon's opposition, Members of Parliament assembled sufficient strength in the House of Representatives to pass the bill. When it arrived in the Legislative Council, two previously hostile members, moved to anger at Seddon's "underhand" behaviour in getting one member to change his vote, voted in favour of the bill. Hence the bill was passed by 20 to 18, and with the Royal Assent it was signed into law on 19 September 1893. It is often said by this measure New Zealand became the first country in the world to have granted women's suffrage.

In the 1893 general election women voted for the first time, although they were not eligible to stand as candidates until 1919.

An analysis of men and women on the rolls against the votes recorded showed that in the 1938 election 92.85% of those on the European rolls voted; men 93.43% and women 92.27%. In the 1935 election the figures were 90.75% with men 92.02% and women 89.46%. As the Māori electorates did not have electoral rolls they could not be included.[16][17]

Voting rights extended to seamen

From 1908, several legislative amendments extended voting rights to seamen who lived on their ships so did not have a residential address to qualify as an elector; subsequently several electoral rolls had "seamens' sections" with many addresses shown as their ship.[18]

Lowering the voting age

For most of New Zealand's early history, voters needed to have attained at least 21 years of age in order to vote. At times, legislative changes (in 1919 and 1940) temporarily extended voting rights to people younger than this, such as in World War I and World War II (when serving military personnel could vote regardless of age and despite not being resident at an address in New Zealand). Later, Parliament reduced the voting age further; in 1969 to 20 years of age, and in 1974 to 18. This extension of the franchise occurred in part in an atmosphere of increased student interest in politics due to the Vietnam War protests.

In 2018, Children's Commissioner Judge Andrew Becroft expressed the view that there would be benefit in lowering the voting age from 18 to 16 years of age.[19] Becroft believes this may be one way to counter the trend of youth disengagement from democratic processes and declining levels of voting at the legal age. The argument follows that an important component of engagement is the ability to influence government policy.

On 21 November 2022, the Supreme Court in the Make It 16 Incorporated v Attorney-General case ruled that the voting age of 18 in elections is "inconsistent with the right in section 19 of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 to be free from discrimination on the basis of age" and further emphasised that inconsistency had not been justified under section 5 of the Bill of Rights. The Supreme Court granted a formal declaration of inconsistency is required to be reported to Parliament by the Attorney-General.[20] Despite the court's ruling, as Parliament is supreme, only it can decide to change the voting age.[21][22][23]

Changes to local government elections

Peter Fraser's Labour Party passed the Local Elections and Polls Amendment Act 1944,[24] replacing the restriction that only land-owning ratepayers in county areas could vote in local elections, with a three-month residency qualification.[25] It also allowed employees to stand for election to the local body employing them.[26] It was strongly opposed by farmers,[27] and Oroua Council even advocated a rates and taxes strike.[28] The Act resulted in a significant extension of the franchise, especially in rural towns.[29]

As described in the Local elections in New Zealand article, an individual who owns more than one property may still be eligible to vote in more than one voting area for local elections.

Overseas voting

The Electoral Act 1956 allowed New Zealanders to vote from overseas: it functioned predominantly as a consolidatory and simplifying act. During both world wars, military personnel serving overseas had been able to vote, but prior to 1956 civilians could not vote from overseas. Currently, a New Zealand citizen loses eligibility to vote while overseas if they have been out of the country for more than three consecutive years.

Abolition of the citizenship requirement

In 1975, Parliament extended the voting franchise to all permanent residents of New Zealand, regardless of whether or not they possessed citizenship. One cannot, however, gain election to parliament unless one holds New Zealand citizenship. (One party-list candidate in the 2002 election, Kelly Chal, could not assume her position as a member of parliament because she did not meet that criterion.)[30]

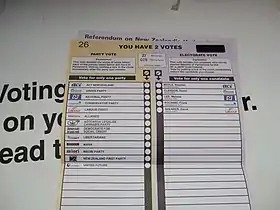

Switch to MMP

Apart from a brief period from 1908 to 1913, when elections used runoff voting, New Zealand used the first-past-the-post electoral system until 1996. Gradually, single-member electorates replaced multi-member electorates in urban areas, and single-member first-past-the-post electorates became the norm for most of the twentieth century. Nineteenth century Prime Minister of New Zealand Harry Atkinson was a known advocate of a proportional voting system, though he was largely ignored at the time.[31]

Towards the end of the twentieth century, however, voter dissatisfaction with the political process increased. In particular, the 1978 election and the 1981 election both delivered outcomes that many deemed unsatisfactory; the opposition Labour Party won the highest number of votes, but Robert Muldoon's governing National Party won more seats. This sort of perceived anomaly occurred as a direct result of the first-past-the-post electoral system. Subsequently, voter discontent grew even greater when many citizens perceived both Labour and National to have broken their election promises by implementing the policies of "Rogernomics". This left many people wanting to support alternative parties, but the electoral system made it difficult for smaller parties to realistically compete with either of the two large ones – for example, the Social Credit Party had gained 21% of the vote in 1981, but received only two seats.

In response to public anger, the Labour Party established a Royal Commission on the Electoral System, which delivered its results in 1986. Both Labour and National had expected the Commission to propose only minor reforms, but instead it recommended the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) system already used in Germany. Neither Labour nor National supported this idea, and National chose to embarrass Labour by pointing out their lack of enthusiasm for their own Commission's report. National, attempting to seize the upper ground, promised a referendum on the matter. Labour, unwilling to see itself outdone, promised the same. In this manner, both parties committed to a holding a referendum on a policy that neither supported.

When National won the next election, it agreed (under pressure from voters) to hold the promised referendum. The first, indicative referendum was held on 19 September 1992, and asked voters whether to keep the FPP system or change to a different system, and if there was a majority to change, which system out of four (including MMP) would they prefer. The referendum returned with an 84.7 percent vote in favour of change and 70.3 percent in favour of MMP. A second binding referendum was subsequently held alongside the 1993 general election on 6 November 1993, with voters choosing whether to keep FPP or change to MMP. The referendum was returned with 53.9 percent in favour of changing to MMP.

The first MMP election took place in 1996. Disproportionality as measured by the Gallagher Index has fallen sharply, from an average of 11.10% in the period between 1946 and 1993 to just 1.11% in 2005. In 2008 it increased to 5.21% because New Zealand First was not represented in Parliament, but in 2011 was 2.53% (interim result).

A second referendum on the voting system was held in conjunction with the 2011 general election on 26 November 2011, asking voters whether to keep MMP or to change to another system, and which out of four systems would they prefer if there was a vote for change. The referendum was returned with 57.8 percent in favour of keeping MMP, and apart from one third of the votes in the second question being informal, FPP was the preferred alternative system with 46.7 percent.

Voter turnout in New Zealand's elections

Stats NZ holds information on voter turnout in general and local elections in New Zealand since 1981.[32][33] Although voter turnout has generally declined in recent decades, it has increased in the last three elections.

| Year | Total registered electors (TER) | Voters as % of TER |

|---|---|---|

| 1879 | 82,271 | 66.5 |

| 1881 | 120,972 | 66.5 |

| 1884 | 137,686 | 60.6 |

| 1887 | 175,410 | 67.1 |

| 1890 | 183,171 | 80.4 |

| 1893 | 302,997 | 75.3 |

| 1896 | 337,024 | 76.1 |

| 1899 | 373,744 | 77.6 |

| 1902 | 415,789 | 76.7 |

| 1905 | 476,473 | 83.3 |

| 1908 | 537,003 | 79.8 |

| 1911 | 590,042 | 83.5 |

| 1914 | 616,043 | 84.7 |

| 1919 | 683,420 | 80.5 |

| 1922 | 700,111 | 88.7 |

| 1925 | 754,113 | 90.9 |

| 1928 | 844,633 | 88.1 |

| 1931 | 874,787 | 83.3 |

| 1935 | 919,798 | 90.8 |

| 1938 | 995,173 | 92.9 |

| 1943 | 1,021,034 | 82.8 |

| 1946 | 1,081,898 | 93.5 |

| 1949 | 1,113,852 | 93.5 |

| 1951 | 1,205,762 | 89.1 |

| 1954 | 1,209,670 | 91.4 |

| 1957 | 1,252,329 | 92.9 |

| 1960 | 1,310,742 | 89.8 |

| 1963 | 1,345,836 | 89.6 |

| 1966 | 1,409,600 | 86.0 |

| 1969 | 1,519,889 | 88.9 |

| 1972 | 1,583,256 | 89.1 |

| 1975 | 1,953,050 | 82.5 |

| 1978 | 2,487,594 | 69.2 |

| 1981 | 2,034,747 | 91.4 |

| 1984 | 2,111,651 | 93.7 |

| 1987 | 2,114,656 | 89.1 |

| 1990 | 2,202,157 | 85.2 |

| 1993 | 2,321,664 | 85.2 |

| 1996 | 2,418,587 | 88.3 |

| 1999 | 2,509,365 | 84.8 |

| 2002 | 2,670,030 | 77.0 |

| 2005 | 2,847,396 | 80.9 |

| 2008 | 2,990,759 | 79.5 |

| 2011 | 3,070,847 | 74.2 |

| 2014 | 3,140,417 | 77.9 |

| 2017 | 3,298,009 | 79.8 |

| 2020 | 2,919,073 | 82.2 |

Proposed compulsory voting

Generally declining voting rates have prompted discussion amongst political commentators. Statistics released following the 2011 election found that non-voting was particularly prominent amongst the young, poor and uneducated demographics of New Zealand.[35] Massey University's Professor Richard Shaw has discussed this issue, arguing it is important for the health of public conversation that voices of the community are heard equally. Without increasing voting rates, there is a risk that the inequities which affect the young and impoverished at a disproportionate rate will replicate. Shaw notes that, over time, systematic disengagement from voting has the potential to erode the legitimacy of a political system.[36]

Former Labour Prime Minister Sir Geoffrey Palmer has expressed support for the introduction of compulsory voting to counter this trend. In a 2017 interview, Palmer said that it was the basis of democracy that people should have some compulsory duties. Jim Bolger, former National Prime Minister, agreed with this proposition, commenting that voting should be a 'requirement of citizenship'.[37] The implementation of such a sanction might be modelled alongside an Australian compulsory voting system which inflicts a small fine upon non-voters.

Whilst the possibility of compulsory voting has gained some traction, then-current Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern expressed her hesitation, saying that compulsion is an ineffective way to foster democratic engagement in non-voting demographics.[38]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Elections and campaigns". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ↑ "Political participation and electoral change in nineteenth-century New Zealand". parliament.nz. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ↑ "New Zealand". OECD Better Life Index. 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ↑ Edwards, Bryce (20 June 2012). "Voter participation and turnout". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ↑ "Municipal Corporations Act, 1842" (PDF). NZLII. 18 January 1842.

- 1 2 "Explainer: The Maori seats and their uncertain future". Stuff. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ "Representation Act, 1860" (PDF). NZLII. 20 October 1860.

- ↑ "Representation Act, 1862" (PDF). NZLII. Retrieved 30 June 2018.

- ↑ Taonui, Rawiri (11 September 2017). "Māori seats once again focus of debate heading into general election". Stuff. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ "Municipal Corporations Act 1867 (31 Victoriae 1867 No 24)". New Zealand Legal Information Institute. University of Otago Faculty of Law, University of Canterbury and the Australasian Legal Information Institute (AustLII). Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ↑ Grimshaw, Patricia (1972). Women's Suffrage in New Zealand. Auckland, NZ: Auckland University Press/Oxford University Press. p. 13.

- ↑ "The Nelson Evening Mail". Vol. II, no. 297. 16 December 1867. p. 2. Retrieved 10 January 2021 – via Papers Past.

- 1 2 "The Secret Ballot". Electoral Commission. 15 February 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ↑ "Change in the 20th century". New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 12 July 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ↑ "The Right to Vote". elections.org.nz. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- ↑ New Zealand Official Year-book, 1942 p778

- ↑ "The New Zealand Official Year-Book, 1942". Government Printer. 28 June 2015. Archived from the original on 21 January 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ↑ "New Zealand Maritime Index from NZNMM". nzmaritimeindex.org.nz. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ↑ "Lower voting age to 16, urges Children's Commissioner Judge Andrew Becroft". nzherald.co.nz. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ New Zealand Bill of Rights (Declarations of Inconsistency) Amendment Act 2022 (2022 No 45)

- ↑ Archived 21 November 2022 at the Wayback Machine Make It 16 Incorporated v Attorney-General [2022] NZSC 134

- ↑ Molyneux, Vita (21 November 2022). "Supreme Court rules in favour of lowering voting age to 16". NZ Herald. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ↑ "Supreme Court rules in favour of 'Make It 16' to lower voting age". RNZ. 21 November 2022. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ↑ "Local Elections and Polls Amendment Act 1944". NZLII.

- ↑ "Labour's New Laws (Ellesmere Guardian, 1945-12-11)". paperspast.natlib.govt.nz National Library of New Zealand. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ↑ "ASSOCIATION'S VIEWS (New Zealand Herald, 1945-03-01)". paperspast.natlib.govt.nz National Library of New Zealand. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ↑ "FARMERS' PROTESTS (Evening Post, 1944-04-18)". paperspast.natlib.govt.nz National Library of New Zealand. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ↑ "RURAL REACTION (Bay of Plenty Beacon, 1944-04-28)". paperspast.natlib.govt.nz National Library of New Zealand. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ↑ "NEW FRANCHISE (Auckland Star, 1944-04-22)". paperspast.natlib.govt.nz National Library of New Zealand. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ↑ "Citizenship of members of Parliament". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ↑ Sinclair, Keith (1988). A History of New Zealand. Auckland: Penguin Books. p. 165.

- ↑ "Voter turnout". archive.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ↑ "Voter Turnout Statistics". Electoral Commission. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ↑ "Dates and turnout of New Zealand General Elections from 1853 to 2020". Electoral Commission. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ↑ "Non-voters in 2008 and 2011 general elections". archive.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ Shaw, Richard. "Election 2017: Voter silence means we're destroying our democracy". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

- ↑ McCulloch, Craig. "Former MPs support compulsory voting in NZ". radionz.co.nz. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- ↑ Rudman, Brian. "Compulsory voting not the answer to low turnout". nzherald.co.nz. Retrieved 19 May 2018.