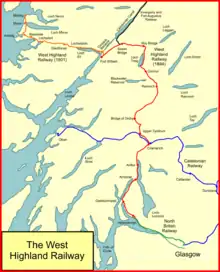

The West Highland Railway was a railway company that constructed a railway line from Craigendoran (on the River Clyde west of Glasgow, Scotland) to Fort William and Mallaig. The line was built through remote and difficult terrain in two stages: the section from Craigendoran to Fort William opened in 1894, with a short extension to Banavie on the Caledonian Canal opening in 1895.

It had originally been intended to extend to Roshven, to give good access to sea-going fishery vessels, but the end point was altered to Mallaig, and this section opened in 1901. The Mallaig Extension was notable for the extensive use of mass concrete in making structures for the line; at the time this was a considerable novelty.

The line never made a profit, and relied on government financial support, which was given (amid much controversy) to improve the depressed economic conditions of the region. It was worked by the North British Railway, which later took the company over. Except for a short stub at Banavie the entire line remains in use, and it is considered to be one of the most scenic railway lines in Britain.[1]

Before the railways

Prior to the nineteenth century the western highlands of Scotland formed a wild tract of land, with mountainous terrain threaded by deep river valleys. The soil was generally poor and not conducive to productive agriculture, and land transport was poor. After the Jacobite rising of 1715 military roads were constructed for the purpose of military control, but these were limited to the area from Crieff to south of the Great Glen. The most efficient transport medium was coastal shipping.

Railways became a practicable means of transport around the end of the eighteenth century especially in mineral districts, in many cases at first as short-distance adjuncts to waterways; the Monkland and Kirkintilloch Railway of 1826 is notable in the development in Scotland. In 1842 the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway opened, showing the way for inter-urban general purpose railways, and the easing of the money market in the following years led to a frenzy of promotion of railways, in which a huge number of schemes were put forward, not all of them viable.[2]

The railway mania

The climax of this was in 1845, the year in which the Caledonian Railway obtained its Act of Parliament, authorising the creation of capital of £1.5 million to build a railway from Edinburgh and Glasgow to Carlisle. Other Scottish trunk railways were authorised in the same year, and this encouraged the promotion of increasingly wild schemes intended to be submitted to Parliament in the following session. The West Highlands of Scotland were not omitted from the schemes proposed. Prospectuses were issued for the Scottish Western Railway and the Scottish North Western Railway, as well as the Scottish Grand Junction Railway and others. Some of the prospectuses told of abundant income and easy construction through imaginary gently rolling land. One line at least admitted the mountainous character of the area but proposed the use of the atmospheric system to overcome the difficulty.

The tightness of money in 1846 and the following years put paid to all the West Highland schemes.

As other railways were opened and operating, there remained a large area on the map of Scotland not served by any, and branch lines from existing trunk lines began to be considered. In 1870 the first section of the Callander and Oban Railway was opened, extending a local branch line, and this railway, a subsidiary of the Caledonian Railway, opened throughout to Oban in 1880.

Also in 1870 the main part of the Dingwall and Skye Railway opened, as far as Stromeferry. Thus two west coast locations were reached by penetrating branches from the centre.[2]

The Glasgow and North Western Railway

There remained considerable tracts of the west Highland area without useful transport routes, and social conditions were identified as being unacceptable. A government commission[note 1] appointed in March 1883, examined the plight of smallholders in the Highlands, and their investigation showed that above all transport was a pressing need.[note 2][3] The Crofters Holdings (Scotland) Act 1886 established the Crofters' Commission and gave enhanced rights to crofters. This change of mood led to the idea that a railway serving the area was a social need, and in turn this led to the promotion of the Glasgow and North Western Railway. This 167-mile line, costed at £1,526,116, was to reach from Glasgow (Maryhill) to Inverness by way of Loch Lomond, Rannoch Moor, Glen Coe and Fort William. Fort William, although a small town, was the centre of a wide area.[3][4]

The G&NWR was not directly established by the government: it was sponsored by financial interests in London, and by the North British Railway (NBR). The NBR was a bitter competitor of the Caledonian Railway (CR) and the CR regarded the western side of Scotland as its own preserve, so that the NBR interest in the new line automatically led to opposition. The Highland Railway and David MacBrayne Ltd, a coastal steamer operator, were both effective monopolies on their respective businesses and naturally opposed the G&NWR. The bill came before Parliament in the 1883 session.[3]

The hearings were lengthy, and opposition counsel did not hesitate to pour scorn on Highlandmen who came in support of the line. The undeveloped nature of the area (which the railway was designed to rectify) was shown as a reason to reject the proposed line, and finally on 1 June 1883 the committee threw out the bill. The G&NWR was finished.[2]

The West Highland Railway proposed

The establishment of the Crofters' Commission followed this disaster, and social concern at the plight of the West Highland population was not diminished by the failure of the G&NWR scheme. In October 1887 public opinion in Fort William begun to be mobilised when the provost N. B. MacKenzie publicly argued for a Glasgow to Fort William line.[3] Efforts were made to secure the support of the North British Railway and in February 1888 this was given, provided that the government contributed £300,000 to the scheme. The North British guaranteed £150,000 if local subscriptions were inadequate, as well as guaranteeing 4.5% on the shares (by a complicated formula).[4]

At length the idea of a West Highland Railway was developed. This time it would not attempt to reach Inverness, but was to run from Craigendoran, on the North British Railway line to Helensburgh. It would run beside the Gare Loch (instead of the southern part of Loch Lomond) to Ardlui, Crianlarich, Rannoch Moor and Loch Treig to Fort William. A branch was to continue to Lochailort and the south-west to Roshven, a west coast sea port intended to give access to fishing vessels and island steamers.

The truncated route passed over the estate of friendly landowners as far as Fort William, but west of that place matters were more feudal, and the Roshven extension was later abandoned in the face of their opposition.

On 30 January 1889 seven gentlemen, including Robert McAlpine set out to walk from Spean Bridge to Rannoch Lodge, a distance of 40 miles across largely trackless terrain. The purpose was to examine the route, and to discuss the route of the line with Sir Robert Menzies. In extremely poor weather they set off, wearing city clothes, and a series of misjudgements nearly led to catastrophe for them.[note 3] This event was used in the parliamentary hearings for the authorisation of the line to illustrate the remoteness of the proposed route.

The projections on the earnings of the line were simply based on the receipts of the Callander and Oban line, grossed up for the longer mileage.[4]

The Highland Railway and the Caledonian Railway both opposed the line in Parliament, to protect their lines to Stromeferry and Oban respectively, but the West Highland Railway Bill obtained royal assent on 12 August 1889. The Roshven extension was dropped and the authorised line was from Craigendoran to Fort William only.[2] Immediately a further bill was prepared for the 1890 session for certain deviations—one on Rannoch Moor was rejected in Parliament—and for an extension to Banavie Pier. This bill was enacted as the West Highland Railway Act 1890.[2][3][4][5]

Construction

The first sod was dug on 23 October 1889[6] and the contractor for the construction, Lucas and Aird, set about assembling the workforce for the construction. The exceptional remoteness of the area, and the scarcity of even basic roadways posed especial difficulties. The engineers were Formans and McCall.

In August 1891 a major dispute arose between the contractors and the railway company, over the price to be paid for removing spoil; the contractor wanted a higher payment for the material containing boulders. The dispute went to Dumbarton Sheriff Court, where the case was found in favour of the railway company, but by now the workforce was largely dispersed. A negotiated settlement brought Lucas and Aird back to the site and work resumed in October 1891.

There was still much to do, in particular the crossing of the boggy section of Rannoch Moor which had not yet been started, By the summer of 1893 the railway company was running out of capital, and it appeared that the work must cease, but one of the directors, Mr Renton, gave part of his personal fortune to save the scheme.[2] In fact when the line was completed the total cost was said to be £1.1 million.[4]

Opening

The line was finally inspected by Major Marindin of the Board of Trade on 3 August 1894[7] (after some earlier visits) and on 7 August authority to open the line to passenger operation was received.[8] Maximum speed was to be limited to 25 mph.[4] Opinion had been expressed within the company that a limited opening to Gareloch at first would be preferable, but the politics of securing government support for the Mallaig line meant that no hesitation could be displayed.[note 4]

Trains started running on that day, although a formal opening was arranged for Saturday 11 August[9] by the wife of the chairman, William Hay, 10th Marquess of Tweeddale.

The line ran from Craigendoran Junction to Fort William, with fifteen stations formed in the style of Swiss chalets. The line was single, with Saxby and Farmer tablet apparatus. There were three passenger trains each way, the first down and last up train conveying a through coach for Kings Cross via Edinburgh; one goods train ran each way daily. On 1 November 1894 the passenger service was reduced to two trains each way, the "winter" timetable. The rival Caledonian Railway introduced a London to Fort William service via Oban, with a steamer connection from there to Fort William, with throughout timings not far off the West Highland times. An attempt was made by the West Highland to operate a residential service from Arrochar to Craigendoran (three return journeys daily and 4 on Saturdays from 1959),[10] there connecting with North British Railway trains to Glasgow, but the difficult location of the WHR stations, some distance from the communities they purported to serve, made this unattractive for daily travel. An attempt to generate goods traffic from Greenock (via steamer to Craigendoran) to Fort William was also unsuccessful because of a price disadvantage compared to throughout steamer transits.

Rannoch station was at this time remote from public roads: the West Highland built a road eastward from the station to Loch Rannoch. (The road is now part of the B846 road. Kinlochleven was also inaccessible by public road at this time.)

From 29 December 1894 through to 7 February 1895 blizzards of exceptional severity struck the area of the line, and many trains became marooned, as the line was blocked. Improved snow defences were subsequently erected, including the Cruach Rock snowshed.[2]

Banavie extension

The 1890 Act for the West Highland Railway included a short branch line from a junction near Fort William to Banavie, at a location adjacent to the Caledonian Canal. This was duly completed and Banavie Pier railway station was opened on 1 June 1895, closing to passengers in 1939 and to freight in 1951. The line arched round to the north-east and there was a station, alongside the canal and some distance north-east of the present-day station. This location was near the head of the series of locks known as Neptune's Staircase by which the canal rises 20 m and a transfer siding adjacent to the canal needed to climb by a 1 in 24 gradient to reach a backshunt.[2][3]

Crianlarich connection

It had always been intended to make a connecting line with the Callander and Oban line of the Caledonian Railway at Crianlarich, where the two lines crossed. The Caledonian Railway had earlier been suspicious of the motives of the North British Railway in this regard; the distance from Glasgow to Crianlarich was substantially shorter by the West Highland Railway and at the Parliamentary stage the West Highland Railway (seen as the creature of the NBR) had applied for running powers to Oban.

The original design of the WHR station at Crianlarich would have allowed through running from Glasgow to Oban via the West Highland, but this was not implemented. The Caledonian Railway suggested a joint station that would have allowed both routes (from Stirling or from Helensburgh) access to both destinations (Oban and Fort William, and there was a proposal that passenger trains from Central Scotland by both routes should combine at Crianlarich and then divide with portions for both Oban and Fort William.

Cattle and other traffic from Lochaber destined for Stirling and Perth were intended to be transferred, but the connection was not made ready until 20 December 1897 and in the meantime that traffic had to be routed via Glasgow. It was complained that this extra mileage was more profitable to the NBR.[2]

From 1962 until 1971 a Swindon-built cross-country DMU, normally used on the Aberdeen to Inverness main line, was transferred in the summer months to work a daily round trip from Glasgow Queen Street station to Oban via this connection.[11] It was joined from late 1965 by all Glasgow to Oban trains, re-routed following closure of the Dunblane to Crianlarich route - initially by a landslide in Glen Ogle but officially from April 1966 [12] as part of the so called Beeching cuts.

Financial performance

With no through trains to Oban and a very limited 'residential' traffic to Garelochhead, the income on which the finances of the line had been based were out of reach. The main line to Fort William opened during the summer season of 1894, but doing so had been expensive, involving excessive construction costs against the contractor's advice in the difficult winters of 1892-3 and 1893-4. Moreover, the Banavie branch would not open until the following year (1895) and total construction costs exceeded £1 million, nearly double the estimate. By now the North British Railway was the banker for the West Highland, but some pretence of independence was retained, to avoid a repudiation of the financial support by the Treasury.[13]

The total revenue of the West Highland Railway in 1896 was £45,146. It climbed to £69,626 in 1899 and eventually to £92,260 in 1901 (equivalent to £10,660,000 in 2021),[14] but it was always heavily loss-making; the losses were made up by the NBR.[2] Quite apart from the NBR's obligations under the guarantee, loans had been granted to the WHR; by June 1902 the WHR owed £1,206,463[15] (equivalent to £139,340,000 in 2021).[14]

Extending to Mallaig

Although on salt water, Fort William was too far from the open sea to be useful as a fishing base, and the idea of a westward extension was revived. Loch Nevis was considered an ideal location from the shipping point of view, but the intermediate land would have made railway construction exceptionally difficult, so the West Highland Railway reluctantly settled on Mallaig, less than 40 miles from Fort William. It was clearly unlikely that the extension could be profitable and the NBR (as the only viable private provider of the necessary capital) made it clear that it would only invest if Government subsidy were made available.

A Treasury Committee[note 5] examined the possible railways—not just the Mallaig line—and recommended Government support for the line, although Mallaig "could only be recommended for want of a more favoured position being attainable."

The North British Railway had supported the first part of the West Highland Railway for commercial reasons, but it was now concerned that it would be expected to pick up the loss of the Mallaig extension, and it considered a loss to be inevitable. Nonetheless commitments had been given, and on 28 April 1892 the NBR agreed to work the extension of 50% of gross receipts, and that it would continue to support the line when the Government guarantee of 3% on capital over 25 or 30 years expired.[3]

Considerable negotiation with Government was necessary over a protracted period in regard to the subsidy, and the matter was badly affected by a change of Government, when the Liberal administration replaced the outgoing Conservative group. A last-minute attempt to get a West Highland (Banavie and Mallaig) Bill in Parliament for the 1893 session was finally refused by the House of Lords. A new Bill, the "West Highland Mallaig Extension Bill" went to the 1894 session.[3]

Authorisation for the subsidy required a quite separate Bill; this was the West Highland Railway (Guarantee) Bill, also in the 1894 session. It was contingent on the construction Bill being passed; satisfactory improvements to Mallaig Harbour had to be agreed, and NBR was to undertake to work the line for 50% of gross receipts in perpetuity.

The Highland Railway opposed the Bill as it was about to extend from Stromeferry to Kyle of Lochalsh. The West Highland Railway (Mallaig Extension) Act passed on 31 July 1894,[16] but the guarantee bill was thrown out; many MPs objected to a free gift to a railway company. However the scheme, aimed at developing a backward area of the country, had Government support and the Guarantee Bill was submitted to Parliament again in the 1895 and 1896 sessions and eventually it passed, on 14 August 1896.[17] The Treasury guaranteed the shareholders 3% on £260,000 of West Highland Railway (Mallaig Extension) capital and to make a grant of £30,000 towards the £45,000 cost of the pier at Mallaig; rates[note 6] were also to be held to the level of unimproved land.[2][3][4]

The first sod of the extension line was cut on 21 January 1897 at Corpach[6] by Lady Margaret Cameron.[18] The contractors were Robert McAlpine and Sons,[note 7] and the engineers were Simpson and Wilson.

Although the section from Banavie to the head of Loch Eil was easy, from there onwards the terrain was very difficult, a problem exacerbated by the remoteness and difficult access. Very hard rock was encountered and away from Loch Eil there was a considerable volume to penetrate. Steam-powered drilling equipment was difficult to bring to the locations and keep fuelled, and McAlpine used water turbines to provide compressed air power for drilling. The construction of the line actually cost £540,000[19] (equivalent to £62,370,000 in 2021).[14]

Although the rock was hard, it was shattered and fractured, making it unsuitable for conventional masonry construction in bridges and viaducts, and this led McAlpine to use mass concrete to build many bridges; at the time this was a revolutionary form of construction. Borrodale Burn bridge became the world's longest concrete span at 127 feet, and Glenfinnan Viaduct was a huge structure in concrete at 416 yards long with 21 arches.[5]

The Mallaig line continued from the existing Banavie branch; the junction (formerly Banavie Junction) near Fort William for the branch was renamed Mallaig Junction, and the point of divergence of the new line from the final section of the Banavie branch was named Banavie Junction. The original Banavie station was renamed Banavie Pier, and there was a new Banavie station on the through line.[3]

Operating from Mallaig

The first trains ran to and from Mallaig on 1 April 1901.[3][6] In the first timetable there was a through carriage and a sleeper to and from Kings Cross, but this was not continued in subsequent years. Fish traffic was very important but it never reached the volumes hoped for; the harbour was difficult in certain conditions (which also limited the reliability of the Hebrides ferry service). The Mallaig site on land was also very restricted and gave rise to complaints from the fish merchants, and delays to punctual running because of difficulty loading trains. In addition, the fish traffic tended to arise in spurts, requiring extra trains and empty return workings.

The area was a stronghold of conventional religious belief and the observance of the Sabbath was strictly enforced, also occasionally leading to difficulty in handling a perishable merchandise like fish.

All in all the line was a serious loss-maker and never reached even the low expectations of it: in the thirteen years from 1901-2 to 1913-4 the line made a trading loss of £72,672 and the Treasury contributed £36,672.[3]

By 1914 private motoring had reduced railway income from the well-to-do estates, and bus services became real competitors in the 1920s.[20]

Absorbed by the North British Railway

As time went on, the independence of the West Highland Railway was increasingly seen as a sham; its line was worked by the North British Railway, and its losses as well as any remaining capital works were funded by the NBR. Competing railways — the Highland and the Caledonian — could clearly see that the NBR was in control.

In 1902 matters were brought to a head when the North British Railway (General Powers) Act abolished West Highland Railway stock and substituted 3% North British Railway stock. Six years later the North British Railway Confirmation Act, 1908, gave the NBR power to absorb the entire WHR undertaking, and this became effective on 31 December 1908. The West Highland Railway had a book value of £2,370,000.[3][6]

Invergarry and Fort Augustus

In 1895 an Invergarry and Fort Augustus Railway was proposed: it was a truly local scheme for a line 24 miles in length, serving a district with almost no population. Although built as a single line railway, land was taken for double track, against the day when traffic developed so as to require that. Its Bill was submitted to Parliament in November 1895. There had long been suspicion between the Highland Railway and the North British Railway about presumed attempts to gain control of the Great Glen: the Highland might attempt to reach Fort William and demand running powers to Mallaig; or the North British might seek to reach Inverness and run from Glasgow via Spean Bridge. Such lines had indeed been proposed in past years. Even the Caledonian Railway might get control of the line and acquire running powers to Mallaig.

The Highland Railway saw the Fort Augustus line as a way for the NBR to reach Inverness, whether or not the scheme was sponsored by the NBR, and the Highland opposed it in Parliament, but the line secured its authorising Act on 14 August 1896. This renewed open hostility between the NBR and the Highland Railway and both proposed new schemes for a line between Inverness and Fort Augustus. The Highland Railway appeared to be gaining Parliamentary support at first (in the 1897 session), but eventually both schemes were thrown out.

The Fort Augustus line was built on a lavish scale, with magnificently decorated structures, through difficult terrain. Work began on constructing the line in 1897, but it was not until 22 July 1903 that the line opened. Contrary to expectation, it was the Highland Railway that operated the line at first; it was far detached from the Highland system, and the arrangement was a political gesture rather than a pragmatic commercial move. In fact the Highland Railway withdrew in 1908 and the North British Railway took over. The financial position of the line was hopeless and when cash injections from wealthy landowners dried up, the NBR withdrew its trains in October 1911.

Following intervention from the County Council, trains resumed operation on 1 August 1913 and the NBR acquired the line on 30 August 1914. Passenger operation finally ceased on 1 December 1933 and the line closed completely on 31 December 1946.[5]

The twentieth century

The West Highland Line of the North British Railway (as the WHR had become) settled down to a stable existence in the twentieth century, although continuing to lose money.

In 1923 the main line railways of Great Britain were "grouped" following the Railways Act 1921 and the North British Railway was a constituent of the new London and North Eastern Railway. In turn this was schemed into British Railways, Scottish Region, when the railways were taken into state ownership in 1948.

In 1924 work started on a huge hydro-electric power scheme which led to the establishment in 1929 of the Lochaber Aluminium Smelter near Fort William. The production of aluminium requires large quantities of electric power, and the decision on location of such a plant is driven by the availability of cheap power. Alcan took over the plant in 1981; the finished metal provided business for the line.[21]

In 1931 the Lochaber power scheme was inaugurated; it required a diversion of nearly 1.5 miles of the line alongside Loch Treig; a dam was built across the northern end and the level of the loch was raised by about 35 feet. The diverted railway is from 78m 100yds to 80m 175yds, and includes a new tunnel 150 yards long.[6]

The long-standing lack of employment in the West Highlands once again prompted government intervention when in 1963 an Act of Parliament was passed under which a grant of £8 million was made to Wiggins Teape to establish a pulp and paper mill at Corpach. This came on stream in 1966, and was known as Scottish Pulp and Paper Mills. The process requires plentiful timber and fresh water, and although the latter was freely available, in the longer term it proved difficult to obtain economically priced timber locally, and the plant was closed in 1991.[22]

In June 1975 Fort William station was relocated, shortening the line a little, in connection with a road scheme.

In 1987 radio electronic token block (RETB) was installed on all of the West Highland Railway system, except for the Fort William station area. RETB enabled safe operation of the long single line sections without signalling staff at stations; the control centre was at Banavie. The points at passing loops at stations were spring operated, and were negotiated at slow speed in the facing direction. To avoid confusion in radio voice exchanges between drivers and the signallers at Banavie, Mallaig Junction was renamed Fort William Junction while Tyndrum Upper station was renamed Upper Tyndrum - both from late 1989.[23]

Topography

| Overview | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locale | Scotland | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dates of operation | 12 August 1889–21 December 1908 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | North British Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stations and locations on the first line were:

- Craigendoran Junction; divergence from the Helensburgh line of the North British Railway;

- Craigendoran; separate station from that on the Helensburgh line, and at a higher level; closed 15 June 1964;

- Helensburgh Upper;

- Row; renamed Rhu 1927; closed 9 January 1956; reopened as Rhu Halt 4 April 1960; closed 15 June 1964;

- Faslane Junction; divergence of Faslane branch;

- Faslane Platform; opened 26 August 1945 :closed 1949;

- Shandon; closed 15 June 1964;

- Garelochhead;

- Whistlefield; opened 21 October 1896; Whistlefield Halt from 1960; closed 15 June 1964;

- Glen Douglas Halt; opened 1894 or 1895. From September 1926 for families of railway staff, particularly in connection with the LNER school there; opened to the public 12 June 1961; closed 15 June 1964;

- Arrochar and Tarbet;

- Ardlui;

- Glen Falloch; unadvertised station for workmen employed on Loch Sloy hydro-electric power scheme; opened 10 April 1946; closed circa 1948;

- Crianlarich; also known as Crianlarich Upper from 1953; divergence of spur to Oban line;

- Upper Tyndrum; previously known as Tyndrum Upper;

- Bridge of Orchy;

- Gorton; Private station opened 1894. Location of a school for railwaymen's children; trains called from 1938 to 1964 and possibly 1968; sometimes spelt Gortan;

- Rannoch;

- Corrour; originally intended to be merely a passing place[2] but from the start a private station for Corrour Lodge and Estate; opened for public use 11 September 1934;

- Fersit Halt; opened 1 August 1931; closed 1 January 1935;

- Inverlair; renamed Tulloch 1895;

- Roy Bridge;

- Spean Bridge;

- Banavie Junction; later renamed Mallaig Junction; later renamed Fort William Junction;

- Fort William; relocated about half a mile north (and line shortened accordingly) on 9 June 1975.

Banavie branch:

- Banavie Junction, above; renamed Mallaig Junction when the Mallaig line was opened;

- Banavie Junction; inaugurated when the Mallaig line was opened;

- Banavie; renamed Banavie Pier 1901; last passenger train ran 2 September 1939.

Mallaig line:

- Banavie Junction, above;

- Banavie;

- Corpach;

- Loch Eil Outward Bound; opened May 1985;

- Locheilside;

- Glenfinnan;

- Lech-a-Vuie; opened April 1901; a private halt used by shooting parties on the Inverailort Estate and by the forces in WII; Closed in the 1970s

- Lochailort;

- Beasdale; originally a private station for Arisaig House; opened for public use 6 September 1965;

- Arisaig;

- Morar;

- Mallaig.[6][24]

The ruling gradient of the section from Craigendoran to Fort William is 1 in 50, but the line to Mallaig has a ruling gradient of 1 in 40. Seventeen sea wall sections were required between Corpach and Kinlocheil, as Loch Linnhe can be very rough in bad weather. There are eleven tunnels on this section, although originally only two were planned; the longest tunnel is 350 yards long, at Borrodale. There is a swing bridge at Banavie over the Caledonian Canal, and at Glenfinnan the concrete viaduct is 416 yards long on a 12-chain curve; there are 21 arch spans.[6]

There were 350 viaducts and underbridges and 50 overbridges on the Fort William section. The longest viaduct is on Rannoch Moor at 684 feet in nine spans of 70 feet 6 inches, partly on a 12 chain radius curve. On the Banavie branch the viaduct over the river Lochy, consisting of four 80 feet spans, required cast iron cylinders to be sunk for the founding of the piers.

The Cruach snow shed, at 205 yards long, had a corrugated iron roof in three sections; in summer the centre section was removed; in 1944 it was said to be the only snow shed on a British railway.[6]

There was a level crossing with remotely operated gates about 150 yards from Fort William station. Originally it was manually operated but from 1927 it was electrically worked and controlled from Fort William signal box, a novelty at that time.[6]

The summit of the line is at Corrour, 1,347 feet above sea level.[6]

Current status

Apart from the last section of the Banavie Branch, and several of the southern stations, the line is still open, being operated by ScotRail as part of the West Highland Line services (which also encompasses services to Oban and Mallaig).

Notes

- ↑ The Napier Commission, The Royal Commission of Inquiry into the conditions of the Crofters and Cottars in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland.

- ↑ As well as proposals on land tenure, the urged improved communication by post, telegraph, roads, steam vessels and railways, citing the precedent of state support for the Wade Military Roads and the Caledonian Canal.

- ↑ McGregor (page 56) refers to this as "a foolhardy expedition".

- ↑ McGregor states that it was unprecedented to open a line of over 100 miles in a single action.

- ↑ Special Committee on the improvement of Railway Communication on the West Coast of Scotland.

- ↑ Local taxes normally assessed on the presumed rental value of buildings and other installations.

- ↑ Thomas and Turnock state (page 278) that "the original contractor [before McAlpine] was obliged to withdraw.

References

- ↑ "Highland train line best in world". BBC News. 6 February 2009. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 John Thomas, The West Highland Railway, David and Charles (Publishers) Limited, Newton Abbot, 1965 revised 1976, ISBN 0 7153 7281 5

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 John McGregor, The West Highland Railway – Plans Politics and People, John Donald, Edinburgh, 2005, ISBN 9780859766241

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 David Ross, The North British Railway: A History, Stenlake Publishing Limited, Catrine, 2014, ISBN 978 1 84033 647 4

- 1 2 3 John Thomas and David Turnock, A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume 15: North of Scotland, David & Charles (Publishers), Newton Abbot, 1989, ISBN 0 946537 03 8

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 The Story of the West Highland, published by the London and North Eastern Railway, 1944 (written anonymously by George Dow)

- ↑ "West Highland Railway". Edinburgh Evening News. Scotland. 3 August 1894. Retrieved 3 May 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "North British Railway. Opening of the West Highland Railway for Traffic". Dundee Courier. Scotland. 9 August 1894. Retrieved 3 May 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "West Highland Railway. The Official Opening". Glasgow Herald. Scotland. 13 August 1894. Retrieved 3 May 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "More diesel trains in Scotland". Railway Magazine. November 1959. Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- ↑ Scottish Region timetables for this period

- ↑ Reshaping of British Railways by Richard Beeching, published in 1963

- ↑ McGregor, page 142

- 1 2 3 UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ↑ Donald G B Cattanach, Wieland of the North British Railway, unpublished manuscript, quoted in Ross.

- ↑ "Glasgow Herald". Glasgow Herald. Scotland. 1 August 1895. Retrieved 3 May 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Hansard, House of Lords, 14 August 1896".

- ↑ "Lochiel on the prospect of the West Highland Railway". Inverness Courier. Scotland. 26 January 1897. Retrieved 3 May 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Dr T Timins BA, The Mallaig Extension of the West Highland Railway in the Railway Magazine May 1901

- ↑ John McGregor, West Highland Extension: Great Railway Journeys Through Time, Amberley Publishing, Stroud, 2009, ISBN 978 14456 13383

- ↑ Henry Hewlett (editor), Long-term Benefits and Performance of Dams: Proceedings of the 13th Conference of the British Dam Society, Thomas Telford, London, 2004, ISBN 0 7277 3268 4

- ↑ Richard Leslie Hills, Papermaking in Britain 1488-1988: A Short History, Bloomsbury Academic Collections, London, 1988 revised 2105, ISBN 978-1-4742-4127-4

- ↑ Information from former ScotRail Business Manager Highland 1986-91.

- ↑ M E Quick, Railway Passenger Stations in England Scotland and Wales—A Chronology, The Railway and Canal Historical Society, 2002

Further reading

John McGregor, 100 years of the West Highland Line. 1994. ScotRail.

John McGregor, The West Highland Railway 120 Years, Amberley Publishing, Stroud, 2014, ISBN 978 144 5633459

John McGregor, West Highland Line, Amberley Publishing, Stroud, 2013, 978 144 5613369

John McGregor, The New Railway: The Earliest Years of the West Highland Line, Amberley Publishing,Stroud, 2015, ISBN 978 14456 47326

North British Railway Company, Mountain Moor and Loch: On the Route of the West Highland Railway, David and Charles, Newton Abbot, 1895 facsimile reprint 1972, 978-0715354223

John Thomas, The North British Railway: volume 2, David and Charles, Newton Abbot, 1975, ISBN 0 7153 6699 8

John Thomas, The West Highland Railway, David and Charles, Newton Abbot, 1965, ISBN 0-7153-7281-5.

Roland Paxton and John Shipway, Civil Engineering Heritage: Scotland, Highlands and Islands, Thomas Telford Publishiung, London, 2007, ISBN 978-07277 3488 4

See also

External links

- Railscot on the West Highland Railway

West Highland Railway travel guide from Wikivoyage

West Highland Railway travel guide from Wikivoyage