William Carstares | |

|---|---|

William Carstares c. 1700 | |

| Born | 11 February 1649 |

| Died | 28 December 1715 (aged 66) |

| Occupation | Minister |

| Spouse |

Elizabeth Kekewich (m. 1682) |

.png.webp)

William Carstares (also Carstaires) (11 February 1649 – 28 December 1715) was a minister of the Church of Scotland, active in Whig politics.

Early life

Carstares was born at Cathcart, near Glasgow, Scotland, the son of the Rev. John Carstares, a Covenanter. He was educated at the University of Edinburgh, and then at the University of Utrecht.[1] In the Netherlands he had an introduction to Gaspar Fagel. Through Fagel he met the Prince of Orange, the future King William III of England and II of Scotland, and began to take an active part in politics.[2]

During the Third Anglo-Dutch War, Carstares acted as an intelligence agent for the Prince of Orange, making journeys to England as "William Williams". He corresponded with Pierre du Moulin (died 1676), who ran the Prince's espionage. He was suspected by the English, and arrested by warrant in September 1674 on English soil.[2]

1674 to 1689

Carstares was then committed to the Tower of London; the following year, 1675, he was transferred to Edinburgh Castle. He was believed to be concerned with Sir James Stewart in the authorship of a pamphlet An Account of Scotland's Grievances by reason of the D. of Lauderdale's Ministrie, humbly tendered to his Sacred Majesty (1674).[1] John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale himself got Carstares to admit he had been involved in printing the pamphlet. Lauderdale used the threat of the torture of the boot, which could be employed legally in Scotland; but Carstares was not tortured. In August 1679 he was released, one of the government sops to Scottish opinion after the Battle of Bothwell Bridge.[2] He cannot, therefore, have been the William Carstares who was the chief prosecution witness at the trial of William Staley (the first of the Popish Plot trials) in November 1678, although that Carstares was also a Scotsman, and like his namesake is said to have acted as an intelligence agent.

After this, Carstares visited Ireland, joined nonconformist circles in London, and then in 1681 became pastor to a congregation at Theobalds, near Cheshunt in Hertfordshire. The aftermath of the Exclusion Crisis saw him directly involved in conspiracy with the Whig faction. Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll in the Netherlands was in touch with Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury. Carstares provided liaison, while his brother-in-law William Dunlop was able to use his colonial project in the Province of Carolina as cover for Shaftesbury's preparations for rebellion.[2]

During 1682 Carstares was in the Netherlands, but the following year he was again in London. He was implicated in the Rye House Plot, and arrested in July 1683 at Tenterden, Kent, using an assumed name. He denied knowing any of the plot, though he had heard assassination rumours from Robert Ferguson. He was again threatened with torture in London, this time by Sir George Mackenzie. Once more he was transferred to Edinburgh.[2]

In July 1684 the Privy Council of Scotland tortured William Spence, Argyll's agent, and Carstares was implicated. Carstares himself, who had seen poor health in his detention, was tortured in September, with the thumbikins, and then the boot, clumsily applied. The next day John Drummond, Secretary of State in Scotland, made a deal with Carstares that his answers would not be used in court, and had a doctor see him. Carstares then replied to the questions of the council. He signed a statement, managing to conceal the covert links to Dutch supporters, and the government published it. Later that month he was moved to Stirling Castle.[2]

In the trial of Baillie of Jerviswood, Mackenzie as Lord Advocate found a way to use the statement by Carstares to secure a conviction; Baillie was hanged, drawn and quartered in December 1684. Carstares was freed, and went to London, and then to The Hague shortly before the Monmouth Rebellion, as an adviser to the Prince of Orange.[2]

Under William III

Carstares was court chaplain to William as Prince of Orange, and at the time of the Williamite Revolution, sailed with the Prince to Torbay. He continued as royal chaplain for Scotland, once William was king of Great Britain. He was the confidential adviser of the king, especially with regard to Scottish affairs.[1] He advocated that a Presbyterian polity should replace the Scottish bishops, and the immediate events of the Williamite conflicts bore out his opinion in practical terms.[2] His subsequent influence on matters concerning the Kirk, as a courtier, earned him the nickname "Cardinal Carstares".[3] He also manipulated the Parliament of Scotland, helped by being able to read James Johnston's mail.[2] He was Queenberry's man at court in 1700.[4]

Later life

On the accession of Queen Anne, Carstares retained his post as Royal Chaplain in Scotland, residing in Edinburgh, having also been elected Principal of the University of Edinburgh in 1703. He was a reforming administrator, introducing the Dutch professorial system of teaching. From 1704 he was also "second charge" minister of Old Greyfriars under Rev James Hart in Edinburgh, and from 1706 was second charge of St Giles'[2] under Rev George Hamilton.[5]

He was four times chosen Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, in 1705, 1708, 1711 and 1715.[1][6]

He took an important part in promoting the Union, and was consulted by Harley and other leading Englishmen concerning it. During Anne's reign, the chief object of his policy was to frustrate the measures which were planned by Lord Oxford to strengthen the Episcopalian Jacobites, especially a bill for extending the privileges of the Episcopalians and the bill for replacing in the hands of the old patrons the right of patronage, which by the Revolution Settlement had been vested in the elders and the Protestant heritors.[1]

On the accession of George I, Carstares was appointed, with five others, to welcome the new dynasty in the name of the Church of Scotland. He was received graciously, and the office of royal chaplain was again conferred upon him. A few months after he was struck with apoplexy, and died on 28 December 1715.[1]

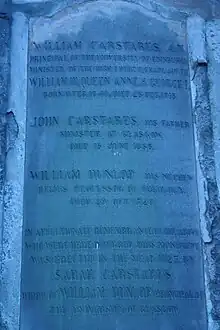

He is buried in Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh. The grave lies amongst the large monuments on the outer walls of the original churchyard, towards the southwest, slightly northwest of the Adam mausoleum.

Family

On 6 June 1682 Carstares married Elizabeth, daughter of Peter Kekewich of Trehawk in Cornwall, who died in 1724. They had no children.[7]

He was uncle by marriage to William Dunlop (1692–1720).[8]

Publications

- The Scottish Toleration Argued (1712)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Carstares, William". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 411.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Clarke, Tristram. "Carstares, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4777. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ A. J. Youngson (2001). The Companion Guide to Edinburgh and the Borders. Companion Guides. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-900639-38-5.

- ↑ P. W. J. Riley (1979). King William and the Scottish Politicians. John Donald. p. 144. ISBN 0-85976-040-5.

- ↑ Fasti Ecclesiae Scoticanae; by Hew Scott

- ↑ John Warrick, The Moderators of the Church of Scotland from 1690 to 1740 (1913), p. 158; archive.org.

- ↑ Stephen, Leslie, ed. (1887). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 9. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ↑ Inscription on the Carstares grave, Greyfriars Kirkyard