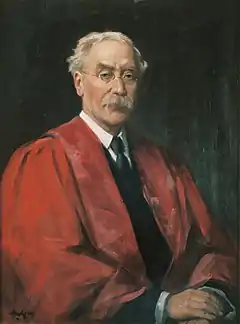

Sir William Leslie Mackenzie | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Henry Wright Kerr, 1929 | |

| Born | 30 May 1862 |

| Died | 28 February 1935 (aged 72) Edinburgh, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Citizenship | British |

| Alma mater | Aberdeen University |

| Known for | Rural health |

| Spouse | Dame Helen Carruthers Mackenzie (13 April 1859 – 25 September 1945) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Public Health |

Sir William Leslie Mackenzie MD FRSE (30 May 1862 – 28 February 1935) was a Scottish doctor renowned in the field of public health, best known for his efforts to systematise rural healthcare and his contributions to the study of child and maternal health.

Early life

William Leslie Mackenzie was born into a small farming community called Shadwick Mains, in Rossshire, Scotland, to James Mackenzie and his wife, Margaret McKenzie.[1] He attended his local one-room school until the age of fourteen, serving as a pupil-teacher for his last three years there. He then attended grammar school in Aberdeen. Mackenzie remained there until age sixteen and then taught for a time at a private girls’ school.[2] He graduated from Aberdeen University with an MA in classics and philosophy (with first class honors), winning various scholarships along the way including the Ferguson and Fullerton awards in mental philosophy. Upon receiving his degree, Mackenzie continued his studies at Edinburgh University for one term. During his studies, he was influenced greatly by Alexander Bain and was a one-time associate of Edwin Chadwick, another major public health figure.[3] He married Helen Carruthers Spence on 12 February 1892. They had no children. Helen pursued an active political career including supporting women's emancipation and the right to vote,[4] and also served on many health boards and committees.[1]

Medical career

Mackenzie decided to enter medicine and was awarded a bursary to attend Aberdeen. He graduated M.B., C.M. with honors in 1888, and later held the position of resident physician at the Aberdeen Infirmary. He later served as an assistant to the university's professor of physiology, Matthew Hay.[3] Obtaining his public health diploma in 1890, Mackenzie became the assistant medical officer at Aberdeen.[2] He transferred the following year to serve as the Kirkcudbrightshire and Wigtownshire county medical officer.

In 1895, Mackenzie's work with rural water supplies earned him high honors.[3] Appointed medical officer for Leith in 1894, he succeeded in dealing with an outbreak of smallpox where his predecessor had failed. In addition to the water supply improvements, he introduced immediate disinfection of homes following a tuberculosis outbreak, “rigorously attended to” outbreaks of diphtheria, and instituted the regular medical inspection of children and milk provision for expecting mothers.[2]

While Mackenzie was quickly becoming a major player in his field, complaints from MPs on the state of medical provision in the highlands prompted even more change. In response to these grievances, he was appointed the Scottish Local Government Board's first medical inspector in 1901.[1] The following year, he and his wife Helen collaborated on the 1903 Royal Commission for Scotland report on the health of school children in Edinburgh. Helen Mackenzie organised the studies and wrote the reports, and was present while he examined the children.[4] The report demonstrated conclusively that the poor health condition of inner city children was related to poverty and Mackenzie presented it to the royal commission after they had surveyed 600 schoolchildren and recommended that teachers be trained in health issues. This report led to the introduction of a school meals service and medical inspection after much debate in Parliament,[2] and recommendations were included in the 1908 Education (Scotland) Act.[4] Mackenzie's career continued to be punctuated by fierce arguments and strong defense of his own medical findings and beliefs. In 1902, he vigorously disagreed with the Scottish medical establishment on the infectivity of tuberculosis at a meeting in Edinburgh of the Medico-Chirurgical Society. Mackenzie suggested environmental factors, public health issues he was already working to reform. He was met with opposition from Sir Henry Littlejohn and others who blamed individual habits instead.

Despite butting heads with a few colleagues, Mackenzie's professional reputation only improved.[3] In 1904, he was appointed the medical member of the Scottish Local Government Board until 1917, becoming later with the name change, a member of the Board of Health for Scotland until his 1928 retirement.[2] While he sat on the board he gave evidence for the care of elderly and feeble minded (1908), strongly opposed the eugenics movement and the poor laws (1909) and called for a preventative health service run by the local authority instead.[1] Mackenzie was passionate about removing the “stigma of pauperism” and believed that healthcare for the poor was a government responsibility.

Mackenzie served on a number of other commissions during his long and productive career. One of the most notable was the royal commission on housing between 1913 and 1917. He actively drafted topics to be addressed and even took an interest in drafting the 1919 Housing Bill itself. His champion cause was to introduce state-subsidised council housing.[3] He was considered by his peers to have played an effective role in the inclusion of this issue.

Public health legacy

As a Highlander, Mackenzie was especially invested in developing a healthcare plan for his home. His treatment plan was designed to overcome the great difficulties associated with providing medical care for a small population scattered over a wide area where transport is usually difficult. This detailed plan became an extremely successful model.[1] This success was recognised when Mackenzie was invited to Kentucky in 1928 to inaugurate a new hospital and nursing service in a mountainous region. His system was also implemented in Canada, Newfoundland, and South Africa.

In addition to his contribution to systematising rural healthcare, Mackenzie's contributions in the field of child and maternal health are invaluable. One of his books, The Medical Inspection of School Children, published with Dr. Edwin Matthew was the first to give any form of substantial evidence for the establishment of medical inspection for children.[3] While legally his manuscript did not cause immediate changes, it provided a foundation for future reform.[1] The services Mackenzie lobbied for were properly coordinated in 1919, shortly after the Education Act of 1918. In 1915, his report for the Carnegie Trustees, Scottish Mothers and Children, set the framework for establishing a service specifically catering to the health of mothers and their children. His other notable works include The Health of the School Child (1906) and Health and Disease (1911).[1]

Mackenzie was considered a radical by his peers in terms of promoting a movement of personal fitness rather than trying to control the environment. His colleagues regarded him “with awe, as a radical philosopher who saw medicine not as a palliative nor a means of private gain, but as an instrument of social development”.[3] He was among the first to lead the charge against Chadwick's Poor Laws and saw the value in looking to improve more than just environmental factors. His publications on behalf of the sick pauper, the TB victim, the mother, the school child, and the inner city tenant all embodied his idea of social advancement through positive intervention.[1]

Further recognition and later life

In 1904 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. His proposers were Sir Thomas Clouston, Sir John Sibbald, Cargill Gilston Knott and Alexander Buchan. In 1912 he received an honorary doctorate (LLD) from Aberdeen University.[5]

Mackenzie was knighted by King George V in 1919 and was appointed by the Crown to the General Medical Council. He served as honorary secretary of the Section of State Medicine and as vice president of the Section of State Medicine and Medical Jurisprudence in 1914.[1]

Mackenzie served as president of the Geographical Association for the year 1931 - 1932, making him one of the first health administrators to govern a geographic society.[6] His contributions to the scientific literature helped establish the sub field of medical geography.

Sir Leslie William Mackenzie died on 28 February 1935 in Edinburgh, after enduring a long illness and was cremated on 2 March. He was survived by his wife, who continued her social work.[3]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "SIR W. LESLIE MACKENZIE, M.D. LL.D.Aberd., F.R.C.P.Ed." British Medical Journal. U.S. National Library of Medicine, 09 Mar. 1935. Web. 18 Apr. 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 1 Leslie Mackenzie. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Apr. 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Owner: Mackenzie, William Leslie, Sir." University of Aberdeen. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Apr. 2017.

- 1 2 3 The biographical dictionary of Scottish women : from the earliest times to 2004. Ewan, Elizabeth., Innes, Sue., Reynolds, Sian. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0-7486-2660-1. OCLC 367680960.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0 902 198 84 X.

- ↑ Mackenzie, Leslie (March 1932). "A HEALTH ADMINISTRATOR'S ATTITUDE TO GEOGRAPHY". Geography. 17 (1): 1–10. JSTOR 40558124.