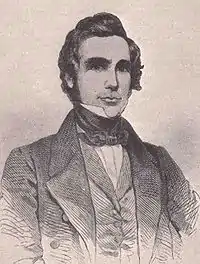

William Lovett (8 May 1800 – 8 August 1877) was a British activist and leader of the Chartist political movement. He was one of the leading London-based artisan radicals of his generation.

A proponent of the idea that political rights could be garnered through political pressure and non-violent agitation, Lovett retired from more overt forms of political activity after a year of imprisonment on the political charge of seditious libel in 1839–1840. He subsequently devoted himself to the National Association for Promoting the Political and Social Improvement of the People, seeking to improve the lives of the poor workers and their children by means of a Chartist educational programme put into practice.

Biography

Early activism

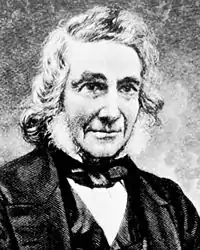

Born in the Cornish town of Newlyn in 1800, Lovett moved to London as a young man seeking work as a cabinet maker. He was self-educated, became a member of the Cabinetmakers Society, and later its President. He rose to national political prominence as founder of the Anti-Militia Association (slogan: 'no vote, no musket'), and was active in wider trade unionism through the Metropolitan Trades Union[1] and Owenite socialism. In 1831, during the Reform Act agitation, he helped form the National Union of the Working Classes with radical colleagues Henry Hetherington and James Watson. After the passage of the Reform Act he turned, with Hetherington, to the campaign to repeal taxes on newspapers known as the War of the Unstamped.

The London Working Men's Association

In June 1836 Lovett founded the London Working Men's Association with several radical colleagues including Hetherington. The LWMA's membership was restricted to 100 working men, although it admitted 35 honorary members including the later Chartist leader Feargus O'Connor. Other honorary members included radical MP's, but the LWMA was strictly a working-class organisation, unlike groups such as the Birmingham Political Union, whose executive was dominated by the middle-class. The original purpose of the LWMA was education, but in 1838 Lovett and fellow Radical Francis Place drafted a parliamentary bill which was the foundation of the Peoples' Charter, and the Association was effectively sidetracked into Chartism. The Bill was signed by Lovett and five other LWMA members, along with six Radical MPs including Daniel O'Connell.

Lovett is best known for his role in the Chartist movement. Chartism, a campaign for parliamentary reforms intended to correct inequities remaining after the Reform Act of 1832, spanned roughly 1838 to 1850.

Arrest and prison term

Like most leading Chartists, Lovett was arrested. In February 1839 the first Chartist Convention met in London, and on 4 February 1839 unanimously elected Lovett as its Secretary. On 13 May 1839 the Convention moved to Birmingham. Many supporters gathered in the city's Bull Ring, but local authorities had prohibited assembly there, and several were arrested. The Convention condemned the actions of police in breaking up the "riot", and posted placards which described the police who put down the riot as a "bloodthirsty and unconstitutional force". Lovett, as secretary, accepted responsibility for the placards, and was arrested along with John Collins, who had taken the placards to a printer. Lovett and Collins were later found guilty of seditious libel, and were sentenced to twelve months imprisonment in Warwick Gaol. They were released in July 1840.

The New life

While in prison Lovett, with Collins, wrote "Chartism, a New Organisation of the People", which focused on Chartist Education. Once released Lovett retired from politics, and in 1841 formed the National Association for Promoting the Political and Social Improvement of the People,[2] an educational body. The body was to implement his New Move educational initiative, through which he hoped poor workers and their children would be able to better themselves. The New Move was to be funded through a 1 penny per week subscription paid by those Chartists who had signed the national petition. Hetherington and Place supported the move, but O'Connor opposed the scheme in the Northern Star, believing it would distract Chartists from the main aim of having the petition implemented. The New Move was unable to generate the popular support that Lovett had hoped for. Membership never surpassed 500,[3] and education was limited to Sunday schools. The National Association Hall was opened in 1842, but closed in 1857 when the operation was evicted. In the 1851 Census Lovett described himself as a school teacher[4] and in the 1861 and 1871 Censuses, a teacher of physiology.[5]

Beliefs

Lovett was a moral-force Chartist, and decried the use or threat of violence to achieve political change. He believed in temperance, and was a staunch advocate of sobriety. Against the educational standards of the time, he believed in teaching methods founded on kindness and compassion.

Personal life

Lovett's father drowned before he was born.

He married Mary Solly from Pegwell, Kent in 1826, and she was a great support to him in his work. They had two daughters.[6]

In later years Lovett opened a bookshop, and completed his autobiography, The Life and Struggles of William Lovett, in 1877.

He died impoverished on 8 August 1877 and was buried on the western side of Highgate Cemetery. His grave is now a grade II listed monument.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ Royal, Edward (1996), Chartism, London: Longman

- ↑ London Chartist 1838–1848 Goodway, David (2002) Cambridge University Press), ISBN 0-521-89364-X; p. 40

- ↑ Joel Wiener, William Lovett (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1989), p. 88.

- ↑ "England and Wales Census, 1851". www.familysearch.org. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ↑ "England and Wales Census, 1871". www.familysearch.org. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ↑ Life and Struggles of William Lovett in His Pursuit of Bread, Knowledge, and Freedom. William Lovett, https://archive.org/details/lifestrugglesofw00love/page/n37/mode/2up?q=mary

- ↑ "Monument to William Lovett in Highgate (Western) Cemetery". www.historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

External links

Media related to William Lovett (Chartist) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to William Lovett (Chartist) at Wikimedia Commons- www.thepeoplescharter.co.uk

- "Biography". Spartacus Educational. (Copyright status unknown)

- "William Lovett and the "New Move"". Chartist Ancestors.

- "William Lovett: Chartist – biography and selected writings". gerald-massey.org.uk (website).

- "Archival material relating to William Lovett". UK National Archives.

- "National Union of the Working Classes". British History Online. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- John Collins : Imprisonment & Bull Ring Riots