The wise fool, or the wisdom of the fool, is a form of literary paradox in which, through a narrative, a character recognized as a fool comes to be seen as a bearer of wisdom.[2] A recognizable trope found in stories and artworks from antiquity to the twenty-first century, the wisdom of the fool often captures what Intellectualism fails to illuminate of a thing's meaning or significance; thus, the wise fool is often associated with the wisdom found through blind faith, reckless desire, hopeless romance, and wild abandon, but also tradition without understanding, and folk wisdom.

In turn, the wise fool is often opposed to learned or elite knowledge.[2] While examples of the paradox can be found in a wide range of early world literature, from Greco-Roman works to the oral traditions of folk culture, the paradox received unprecedented attention from authors and artists during the Renaissance.[2] More than Shakespeare for his range of clownish wise men or Cervantes for his lunatic genius Don Quijote, sixteenth century scholar Erasmus is often credited for creating the definitive wise fool and most famous paradox in western literature[3] through his portrayal of Stultitia, the goddess of folly. Influential to all later fools, she shows the foolish ways of the wise and the wisdom of fools through delivering her own eulogy, The Praise of Folly.[4]

Characteristics

In his article "The Wisdom of The Fool", Walter Kaiser illustrates that the varied names and words people have attributed to real fools in different societies when put altogether reveal the general characteristics of the wise fool as a literary construct: "empty-headed (μάταιος, inanis, fool), dull-witted (μῶρος, stultus, dolt, clown), feebleminded (imbécile, dotard), and lacks understanding (ἄνοος, ἄφρων in-sipiens); that he is different from normal men (idiot); that he is either inarticulate (Tor) or babbles incoherently (fatuus) and is given to boisterous merrymaking (buffone); that he does not recognize the codes of propriety (ineptus) and loves to mock others (Narr); that he acts like a child (νήπιος); and that he has a natural simplicity and innocence of heart (εὐήθης, natural, simpleton).[2]

While society reprimands violent maniacs, destined to be locked away in jails or asylums, the harmless fool often receives kindnesses and benefits from the social elite.[6] Seemingly guided by nothing other than natural instinct, the fool is not expected to grasp social conventions and thus is left to enjoy relative freedom, particularly in his or her freedom of speech.[2] This unusual power dynamic is famously demonstrated through the fool in Shakespeare's King Lear,[7] who works in the royal court and remains the only character who Lear does not severely punish for speaking his mind about the king and his precarious situations. This ability to be reckless, honest, and free with language has greatly contributed to the wise fool's popularity in the literary imagination.

History

Antiquity

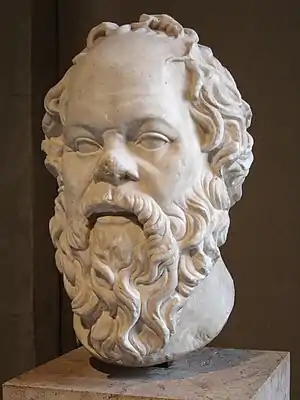

The employment and occupation of the fool played a significant role in the ancient world. The Ancient Greek authors Xenophon and Athenaeus wrote of normal men hired to behave as insane fools and clowns while the Roman authors Lucian and Plautus left records of powerful Romans who housed deformed buffoons famous for their insolence and brazen madness.[2] Plato, through the guise of Socrates, provides an early example of the wisdom of the fool in The Republic through the figure of an escaped prisoner in The Allegory of the Cave.[8] The escaped prisoner, part of a group imprisoned from birth, returns to free his fellow inmates but is regarded as a madman in his attempts to convince his shackled friends of a greater world beyond the cave.

Numerous scholars have long regarded Socrates as the paramount wise fool of classical antiquity.[2] Through what would come be to branded as Socratic irony, the philosopher was known to make fools of people who claimed to be wise by pretending to be an ignorant fool himself.[10] His name also bears a strong association with the Socratic Paradox, "I know that I know nothing," a statement that has come to frame him in the oxymoron of the ignorant knower. In Plato's Apology, this self admission of ignorance ultimately leads the oracle at Delphi to claim there is no man with greater wisdom than Socrates.[11]

Medieval

The wise fool manifested most commonly throughout the Middle Ages as a religious figure in stories and poetry. During the Islamic Golden Age (approx. 750 - 1280 CE), an entire literary genre formed around reports about the "intelligent insane."[6] One book in particular, Kitab Ugala al-majanin, by an-Naysaburi, a Muslim author from the Abbasid Period, recounts the lives of numerous men and women recognized during their lifetimes as 'wise fools.'[6] Folkloric variations of madmen, lost between wisdom and folly, also appear throughout the period's most enduring classic, The Thousand and One Nights. Buhlil the Madman, also known as the Lunatic of Kufa and Wise Buhlil, is often credited as the prototype for the wise fool across the Middle East.[12] Nasreddin was another well-known "wise fool" of the Islamic world.[13]

The fool for God's sake was a figure that appeared in both the Muslim and Christian world. Often wearing little to no clothes, this variant of the holy fool would forego all social customs and conventions and feign madness in order to be possessed with their creator's spirit.[6][14] By the twelfth century in France, such feigning led to the Fête des Fous (Feast of Fools), a celebration in which clergy were allowed to behave as fools without inhibition or restraint.[2] During the Crusades, Christ was recognized as a 'wise fool' figure through his childlike teachings that yet confounded the powerful and intellectual elite. Numerous other writers during this period would explore this theological paradox of the wise fool in Christ, sustaining the trope into the Renaissance.

Renaissance

The wise fool received tremendous popularity in the literary imagination during the Italian and English Renaissances. In Erasmus' Moriae encomium, [The Praise of Folly], written in 1509 and first published in 1511, the author portrays Stultitia, the goddess of folly, and a wise fool herself, who asks what it means to be a fool and puts forth a brazen argument praising folly and claiming that all people are fools of one kind or another.[15] According to scholar Walter Kaiser, Stultitia is "the foolish creation of the most learned man of his time, she is the literal embodiment of the word oxymoron, and in her idiotic wisdom she represents the finest flowering of that fusion of Italian humanistic thought and northern piety which has been called Christian Humanism."[2]

At the same time, Shakespeare greatly helped popularize the wise fool in the English theater through incorporating the trope in a variety of characters throughout many of his plays.[16] While Shakespeare's early plays largely portray the wise fool in comic terms as a buffoon, the later plays characterize the fool in a much more melancholic and contemplative light.[16] For example, in King Lear,[7] the Fool becomes the only one capable of speaking truth to the King and often takes on the role of revealing life's tragic nature to those around him. For Shakespeare, the trope became so well known that when Viola says of the clown Feste in Twelfth Night, "This fellow is wise enough to play the fool" (III.i.60), his audiences recognized it as a popular convention.[2]

Numerous other authors rendered interpretations of the wise fool across the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries from Hans Sachs to Montaigne. The image of the wise fool is as well found in numerous Renaissance artworks by a range of artists including Breughel, Bosch, and Holbein the Younger.[2] In Spain, Cervantes' novel Don Quixote exemplifies the world of the wise fool through both its title character and his companion, Sancho Panza.[17]

Examples in modern literature and film

- Patchface, from George R.R. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire novels: a fool to King Stannis Baratheon who was the only survivor of a shipwreck that killed Stannis' parents. As a result, he was apparently driven mad and makes seemingly nonsensical statements. However, his words seem to prophecy significant events in the series, such as the Red Wedding.[18]

- Gaston Bonaparte, from the Japanese writer Shusaku Endo's 1959 novel Wonderful Fool: protagonist Bonaparte is portrayed as a relative of Napoleon Bonaparte who visits Japan. He bumbles his way through troubles by naively ignoring or not understanding a series of problems and attacks, but leaves his Japanese friends enlightened.[19]

Heimir the Fool, in The Northman movie says “Wise enough to be the fool.”

See also

Further reading

- Idiots, Madmen, and Other Prisoners in Dickens by Natalie McKnight[20]

- "The Wise Fool in the Slavic Oral and Literary Tradition" by Zuzana Profantová[21]

- The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays[22] by Michail Bachtin

- Wise Fools in Shakespeare by Robert Goldsmith[23]

- "The Wisdom of Holy Fools in Postmodernity" by Peter C. Phan[24]

- "Much Virtue In If" (Shakespeare Quarterly) by Maura Slattery Kuhn[25]

Notes

- ↑ Cole, Thomas B. (2009-10-21). "The Court Jester Stanczyk (1480-1560) Receives News of the Loss of Smolensk (1514), During a Ball at Queen Bona's Court". JAMA. 302 (15): 1627. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1372. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 19843889.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Kaiser, Walter (2005). "Wisdom of the Fool". In Horowitz, Maryanne Cline (ed.). New Dictionary of the History of Ideas. Vol. 4. Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 515–520. ISBN 978-0684313771. OCLC 55800981.

- ↑ Behler, E.H. (2012). "Paradox". In Green, Roland; et al. (eds.). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (4th ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691133348. OCLC 778636649.

- ↑ "Moriae encomium, that is, the praise of folly", The Praise of Folly, Princeton University Press, 2015-01-31, pp. 7–128, doi:10.1515/9781400866083-005, ISBN 9781400866083

- ↑ "CalmView: Overview (Swedish Performing Arts Agency)". calmview.statensmusikverk.se. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- 1 2 3 4 Dols, Michael Walters (1992). Immisch, Diana E. (ed.). Majnūn : the madman in medieval Islamic society. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0198202219. OCLC 25707836.

- 1 2 Shakespeare, William (2015-10-20). The tragedy of King Lear. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781501118111. OCLC 931813845.

- ↑ Plato. (2015). Republic. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674996502. OCLC 908430812.

- ↑ "Site officiel du musée du Louvre". cartelfr.louvre.fr (in French). Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary under irony.

- ↑ Plato. (2018-09-18). Apology. Open Road Media. ISBN 978-1504052139. OCLC 1050649303.

- ↑ Otto, Beatrice K. (2001). Fools are everywhere : the court jester around the world. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226640921. OCLC 148646349.

- ↑ Javadi, Hasan. "MOLLA NASREDDIN i. THE PERSON". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- ↑ Tillier, Mathieu (2018). "Un " Alceste musulman " : Sībawayh le fou et les Iḫšīdides" (PDF). Bulletin d'Études Orientales (in French) (66): 117–139. doi:10.4000/beo.5575. ISSN 0253-1623. S2CID 187611672.

- ↑ Levine, Peter (1998). Living without philosophy : on narrative, rhetoric, and morality. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0585062389. OCLC 42855542.

- 1 2 "Shakespeare's fools". The British Library. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- ↑ Close, A. J. (1973). "Sancho Panza: Wise Fool". The Modern Language Review. 68 (2): 344–357. doi:10.2307/3725864. JSTOR 3725864.

- ↑ Martin, George R.R. (2011). A song of ice and fire. Harper Voyager. ISBN 9780007447862. OCLC 816446630.

- ↑ Endo, Shusako (1959), おバカさん Obaka san (Wonderful Fool), Wonderful Fool (Harpers 1974 translated by Francis Mathy, Chuo

- ↑ Natalie., McKnight (1993). Idiots, madmen, and other prisoners in Dickens. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0312085964. OCLC 26809921.

- ↑ Profantová, Zuzana (2009-10-19). "The Wise Fool in the Slovak Oral and Literary Tradition Múdry hlupák v slovenskej ústnej a literárnej tradícii". Studia Mythologica Slavica. 12: 387–399. doi:10.3986/sms.v12i0.1681. ISSN 1581-128X.

- ↑ Bachtin, Michail Michajloviď (2011). Holquist, Michael (ed.). The dialogic imagination : four essays. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292715349. OCLC 900153702.

- ↑ Goldsmith, Robert Hillis (1974). Wise fools in Shakespeare. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0853232636. OCLC 489984679.

- ↑ Phan, Peter C. (2001-12-01). "The Wisdom of Holy Fools in Postmodernity". Theological Studies. 62 (4): 730–752. doi:10.1177/004056390106200403. ISSN 0040-5639. S2CID 73527317.

- ↑ Kuhn, Maura Slattery (1977). "Much Virtue in If". Shakespeare Quarterly. 28 (1): 40–50. doi:10.2307/2869630. ISSN 0037-3222. JSTOR 2869630.