Women's University Club of Seattle | |

| |

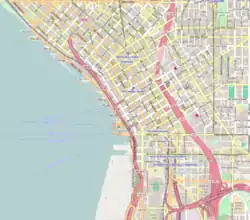

| Location | 1105 6th Ave., Seattle, Washington |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 47°36′28″N 122°19′49″W / 47.60778°N 122.33028°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1922 |

| Architect | Abraham H. Albertson |

| Architectural style | Colonial Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 09000507[1] |

| Added to NRHP | July 10, 2009 |

The Women's University Club of Seattle (WUC) is a social club for women located at 1105 Sixth Avenue in Seattle, Washington.[2]

Founded in 1914 by Edith Backus, the club was a hub for college-educated women. It started with 276 members.[3]

The club's building was added to the National Register of Historic Places on July 10, 2009.[4][5]

Early history

Founded in 1914 by Edith Backus,[3] the Women's University Club of Seattle was part of the women's club movement in the United States.

The women's club movement started in the 1860s in New York City, and Boston, and spread across the United States. These clubs provided an outlet for educated, mostly white, women to engage in their communities, and engage in educational, political, and professional pursuits.[6]

Starting with 276 members,[3] the club originally started at a one-story building at 1250 Fifth Avenue, next to the men-exclusive College Club.[3]

In 1920, both clubs were evicted from their original buildings, and their building razed to make room for what is currently the Olympic Hotel.[3]

WUC members worked with two prominent local architects for their new building, Abraham H. Albertson and Édouard Frère Champney. Both Albertson and Champaney's had been connected with the club prior to new building, as Albertson's wife, Clare, was a member, and Albertson had designed the original building. Champneys mother was a longtime club member. The University Club building is the only time Albertson and Champney collaborated.[3]

When the second building was completed, the club members braided the rugs, embroidered the napkins and linens in the dining room, and hand crafted many of the projects in the club.[3][7]

Bertha Knight Landes, Mayor of Seattle from 1926 to 1928, was the first woman mayor of any major U.S. city, and was a charter member of the club.[8]

World War I and II

During the World War I and World War II, women's clubs were heavily involved in volunteering and war efforts, including working directly with the Red Cross.

Dr. Mabel Seagrave, an early member of the club, traveled to France during World War I, and was in charge of an entirely women-staffed hospital, which cared for 10,000 patients.[9] In 1917, members organize a Red Cross Auxiliary, and 12 members serve overseas with the American Red Cross.

The Great Depression in the United States took a toll on membership, and the club struggled financially. In 1932, a second membership category was added to the club, allowing women without all of the normal education requirements to participate in the club.[10]

In March 1939, first lady Eleanor Roosevelt addressed the club at their 25th anniversary dinner.[9][3][11]

During World War II, the club made a half-million bandages for the red cross.[9] 24 members served overseas in support of the war effort, while others participated in volunteering efforts.[12] In 1943, the club's House and Garden Group created a cookbook, and the first printing generated enough funds for three clubmobiles for servicemen in Alaska.[13]

Post World War II to present

In 1951, membership reached over 1,100, leading to the WUC board to consider expansion. By 1954, the club purchased an adjacent lot, and gained another stream of revenue from the parking lot. Five years later, the club votes to remain in the city and expand on the original building, rather than leave Seattle entirely.[14]

In 1961, the entire building is remodeled, and expansion begins in the parking lot purchased in 1951. The expansion includes a new kitchen and dining room, with parking below. As the University Club building changed, so did the focus of some of the programming at the club. Women's rights became the focus of programming in 1971, including women's legal rights and the sexual revolution.[15]

By 1989, the club relaxes the more formal aspects of club rules, and drops the title of Miss and Mrs. for members, and instead uses first and last names only.[16] By 1991, the club hosts 65 classes for members, with over 1,000 members in the club.[17]

For its centennial celebration of its historic clubhouse in 2014, the club released a booklet detailing the history of the WUC itself, and released a timeline on their website of major events in the club's history.

Notable members

Gallery

University Club building looking west from the corner of Sixth and Spring

University Club building looking west from the corner of Sixth and Spring University Club building entrance on Sixth Avenue

University Club building entrance on Sixth Avenue

References

- ↑ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. November 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Parcel ID 0942000255". Seattle Department of Neighborhoods. Retrieved 2014-12-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Krueger, Olivia. "Women's University Club celebrates 100 years in its downtown home". UW Magazine — University of Washington Magazine. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- ↑ "Seattle's newest historic landmarks". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. 2014-07-30. Retrieved 2014-12-27.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Women's University Club of Seattle". National Park Service. Retrieved January 1, 2020. With accompanying pictures

- ↑ "Women's Clubs". National Women's History Museum. 2014-03-17. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- ↑ "Women's University Club 1921-1930". www.womensuniversityclub.com. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- ↑ "Landes, Bertha Knight (1868-1943)". www.historylink.org. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- 1 2 3 "City's 'best-kept secret' is out". The Seattle Times. 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- ↑ "Women's University Club 1931-1940". www.womensuniversityclub.com. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- ↑ "My Day by Eleanor Roosevelt, March 29, 1939". www2.gwu.edu. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- ↑ "Women's University Club 1941-1950". www.womensuniversityclub.com. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- ↑ "Women's University Club 1941-1950". www.womensuniversityclub.com. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- ↑ "Women's University Club 1951-1960". www.womensuniversityclub.com. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- ↑ "Women's University Club 1971-1979". www.womensuniversityclub.com. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- ↑ "Women's University Club 1981-1990". www.womensuniversityclub.com. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- ↑ "Women's University Club 1991-1999". www.womensuniversityclub.com. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- ↑ Binheim, Max; Elvin, Charles A (1928). Women of the West; a series of biographical sketches of living eminent women in the eleven western states of the United States of America. p. 205. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Mildred Andrews (March 2, 2003). "Landes, Bertha Knight (1868-1943)". HistoryLink. Retrieved 2019-07-23.